Why an Astronaut Is Exploring the 'Mount Everest of Shipwrecks'

What a dive on the Andrea Doria has in common with space exploration

An astronaut who's flown five missions in space and climbed Mount Everest has just wrapped up a scientific mission to what divers call the "Mount Everest of Shipwrecks," the S.S. Andrea Doria.

It's a "huge bucket list thing," admits Scott Parazynski, who co-piloted the five-person crewed submersible Cyclops I to the wreck, which lies off the coast of Massachusetts at a depth of more than 200 feet (61 meters).

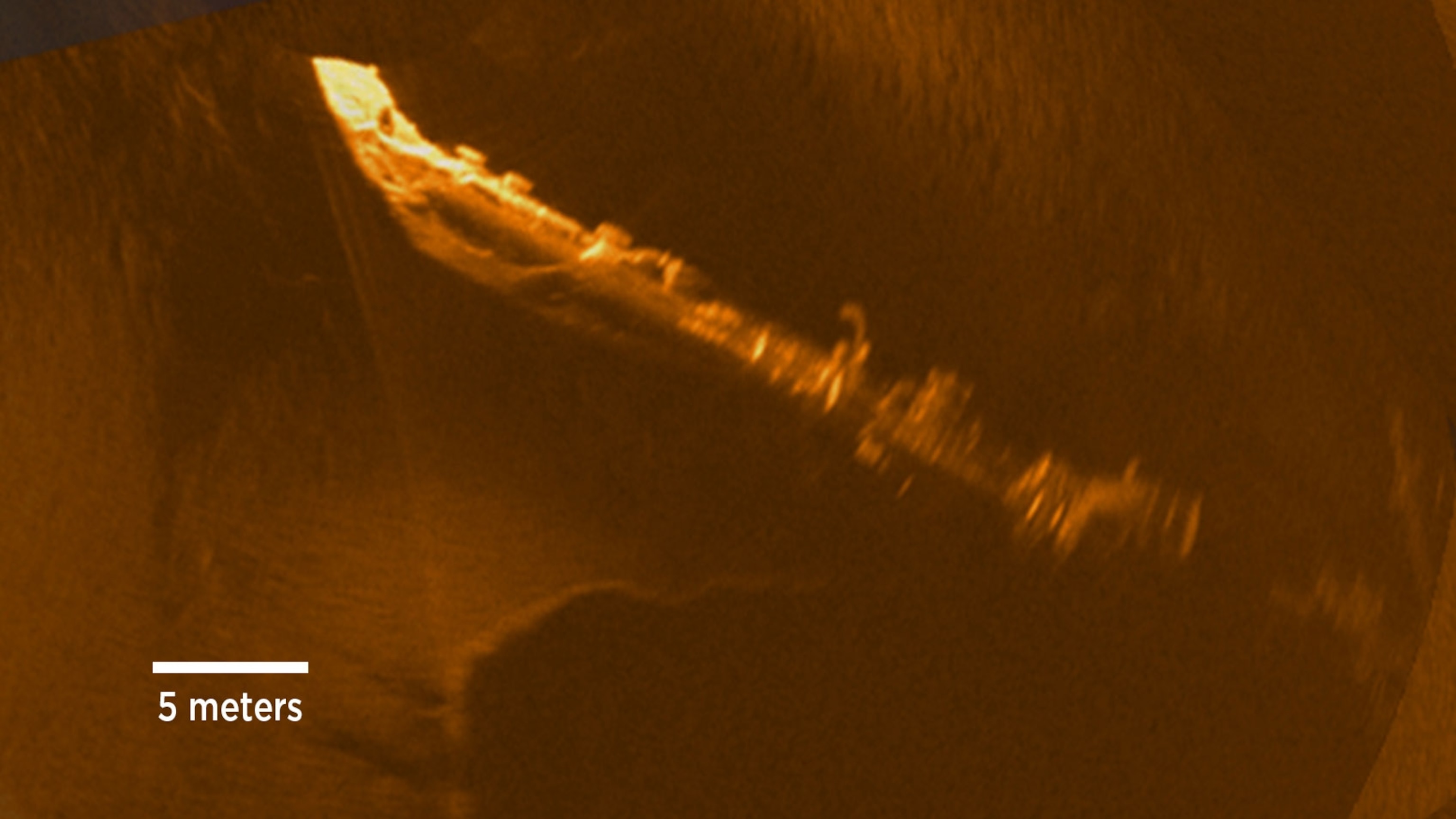

The weeklong expedition to the Andrea Doria, organized by submersible company OceanGate, was designed to collect information on the current condition of the wreck. Researchers on return trips to the wreck will use that information to better understand how modern shipwrecks decay in marine environments.

Sixteen people have died while diving the Andrea Doria, including a neuroscience professor who disappeared on the wreck in 2015.

An Iconic Maritime Tragedy

Now, 60 years after the liner's sinking, the wreck is collapsing as a result of environmental conditions and fishing activity.

The top of the wreck, which was originally in about 160 feet (48.8 meters) of water, has now dropped below 200 feet (61 meters). The majority of the structure is about 240 feet (73.2 meters) deep.

The continued decay of the Andrea Doria means that the shipwreck is becoming more elusive and dangerous to scuba divers. Where it's now located is at least 70 feet (21 meters) deeper than suggested maximum depth for recreational divers.

Steel ships with aluminum superstructures, like the Andrea Doria and so many wrecks from World War II, are very common and potentially polluting.Stockton Rush, CEO, OceanGate

Advanced divers using technical gear and mixed breathing gas can stay less than 20 minutes on the wreck, in conditions that involve strong currents and low visibility. The dangers involved in exploring the remains of the iconic vessel have led divers to dub it the "Mount Everest of Shipwrecks."

Sixteen people have died while diving the Andrea Doria, including a neuroscience professor who disappeared on the wreck in 2015.

What Decaying Wrecks Do to Our Oceans

"Steel ships with aluminum superstructures, like the Andrea Doria and so many wrecks from World War II, are very common and potentially polluting," says Rush. "There's a lot about their decay processes that are not well understood."

From the Bottom of the Atlantic to Seas of Europa

While seeing the remains of the Andrea Doria with his own eyes may be a boyhood dream of astronaut Parazynski, there's a bigger reason why he's co-piloting the vessel that took him to the wreck.

There's just a great synergy going on right now between ocean exploration and space exploration.Scott Parazynski, submersible co-pilot and astronaut

"For instance, what might lie in the waters under the icy crust of [Jupiter's moon] Europa? If we can someday drop a submersible through the ice and swim around there, would we find extremophile life there as well?

"There's just a great synergy going on right now between ocean exploration and space exploration," says Parazynski.

Just as importantly, being part of a crewed mission on a submersible brings advantages to explorers that piloting a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) from topside doesn't offer.

"It's like having MacGyver in the loop; it's about real-time problem solving that really can save the day when it comes to extreme exploration."

Follow Kristin Romey on Twitter.