Ancient Egyptians revered dogs—can this street dog return to that former glory?

With a population over 15 million, Baladi dogs are everywhere—and often mistreated or killed. But that’s starting to change.

Cairo — Walk any city street in Egypt, and you’re likely to encounter a distinctive dog with perked-up ears, spindly legs, and curly tails. Baladi dogs, as they’re called, may number as many 15 million animals across the country—one adventurous pup even ended up at the top of Egypt’s highest pyramid.

The origins of these stray canines—the Egyptian word baladi translates to local—are contested. Some claim that they are mixed-breed descendants of modern breeds, such as Egyptian saluki, Pharaoh hounds, and Canaan dog, while others believe Baladi dogs are their own breed that descends from ancestral dogs revered by the pharaohs.

Though Egyptians have long respected dogs, in recent decades Baladis have been heavily persecuted, with people poisoning, drowning, or beating the animals to death, according to the Society for the Protection of Animal Rights in Egypt (SPARE).

The animals’ negative reputation has various roots, including their rapid reproduction and the fear that they carry rabies. Getting rabies from dogs is rare; on average, 60 people die annually from rabies in Egypt due to animal bites, which can include dogs, according to the latest data from the World Health Organization.

Some people also falsely believe dogs are impure in Islam. Dar al-Ifta, Egypt’s religious advisory council, states that dogs are pure, and that Islamic law prohibits the killing of harmless stray animals, particularly with poison.

To combat Baladis’ bad rap, animal welfare and rescue groups are proposing more humane approaches to managing the dogs. For instance, several Egyptian nonprofits carry out a program called trap, neuter, release, in which Baladi dogs are sterilized and then released back into the streets. (Learn how stray dogs can understand human gestures.)

Other groups, such as My New Life Rescue, have also encouraged people to adopt Baladis, highlighting their intelligence and friendliness. The nonprofit, founded in 2023, maintains a rescue facility in Cairo, where rescuers care for over 70 dogs. Many of them are recovering from severe injuries sustained from life on the street.

“Animal abuse and cruelty in Egypt is so rampant, which puts immense pressure on shelters and animal-rescue services,” says Heidi Gamal, co-founder of My New Life.

Ancient symbols

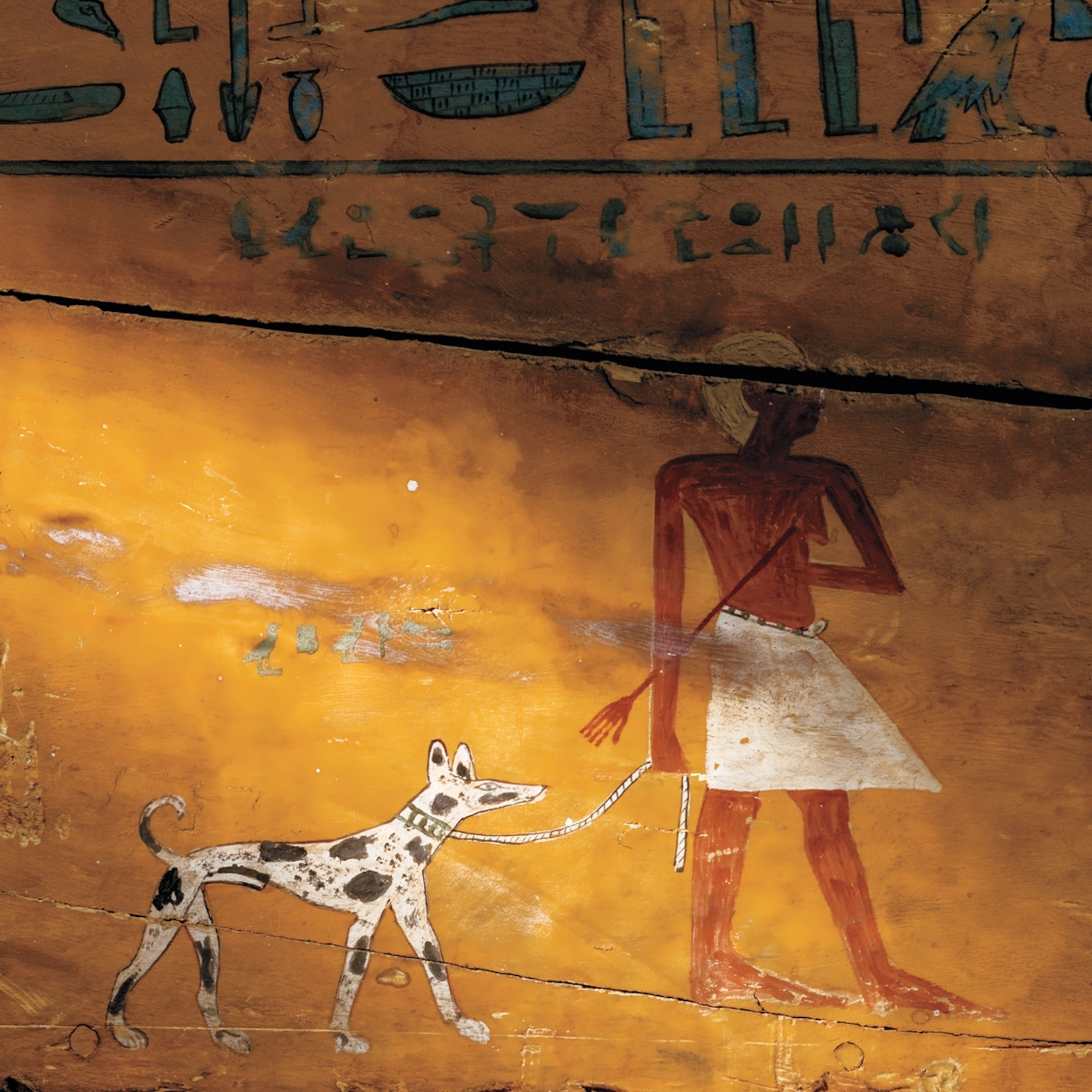

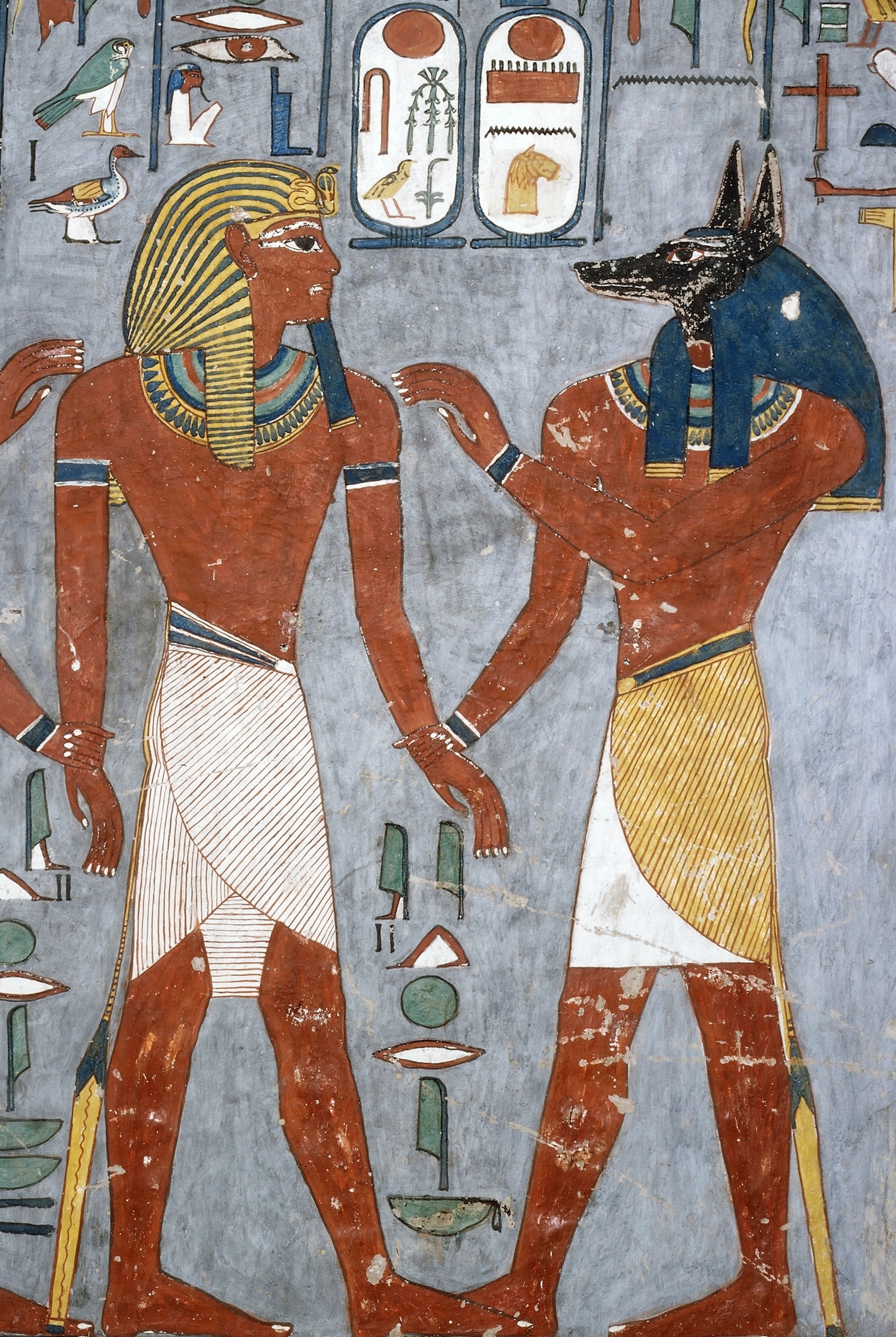

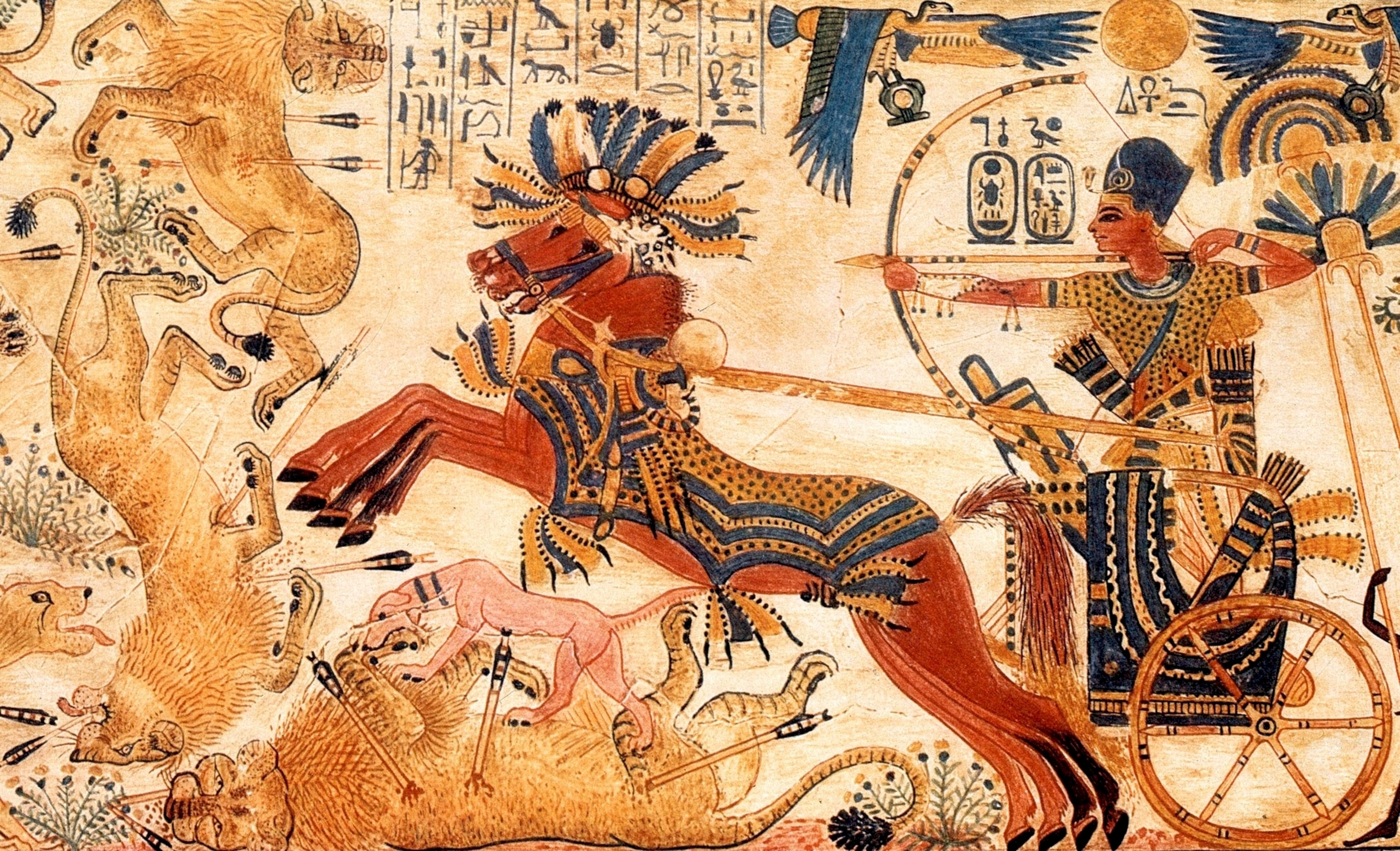

In ancient Egypt, various gods were depicted with domestic dog or jackal heads that resemble modern-day Baladi dogs. Perhaps the most well known is Anubis, the god who guided souls in the afterlife. Many tomb paintings depict canines, including one in Tutankhamun’s tomb that depicts the pharaoh hunting with his dog.

Ancient Egyptians of all social statuses, including the royal family, kept dogs as family pets. Whenever a dog died, the family would mummify their pet and bury it in family tombs, so they could meet again in the afterlife. The family would enter a period of grief, and members would shave their eyebrows as an indicator of such grief.

Per ancient Egyptian religious practices, most Anubis worshipers lived in Saka, a town in Upper Egypt. In Saka, street dogs were free to roam the streets of the town and the halls of Anubis’ temple. (Read how life wasn't easy for elite pets in ancient Egypt.)

Killing dogs was considered an extreme crime that carried heavy sanctions that only intensified if the dog belonged to a person or a family. Yet, murdering dogs with the intent to sacrifice them to Anubis was permissible.

Finding solutions

Today, however, there are few consequences for people who poison or kill Baladi dogs.

The Egyptian penal code does not allow the unjustified murder or poisoning of any domesticated animal, including Baladi dogs. Violators may be imprisoned up to six months or fined up to 200 Egyptian pounds, which is approximately $4.

Egypt’s General Authority for Veterinary Services, affiliated with the Ministry of Agriculture, is responsible for controlling stray dog populations, and regularly puts poison in dog food eaten by stray Baladis. This practice has drawn opposition from many animal welfare groups, such as The Egyptian Society for Mercy to Animals (ESMA) and Animal Protection Foundation. Not only is death by poisoning a cruel way to die, but it can harm other animals or people in the city, according to Gamal of My New Life Rescue.

The veterinary authority did not reply to National Geographic’s requests for comment.

“Poisoning is one of the most painful and inhumane things these dogs have to go through,” says Nada Sherif, a veterinarian at Pet Wellness Clinic in Alexandria, Egypt.

“The chances of treating and saving poisoned dogs are extremely low.”

In 2021, a coalition of animal rights groups and activists filed a lawsuit to end the poisoning. Yet Egypt’s administrative court dismissed the lawsuit, according to the privately owned Egyptian news website Elmasry Elyoum.

In response to the public uproar, some government agencies have slowly adopted trap, neuter, and return as a strategy to lower Baladi dog numbers, though the veterinary services has not said whether they also use this practice. (Learn how dogs are even more like us than we thought.)

“We should trap, neuter, and return 80 percent of the Baladi dogs’ population, while the other 20 percent should be vaccinated and left to reproduce to control the population without eradicating Baladi dogs,” Gamal says.

“However, the trap, neuter, and return strategy should be systematic,” she says—as of right now, it’s not practiced widely enough to make an impact.

Adopt, don’t shop

Gamal seeks sponsors, often recruited through Instagram, to cover a dog’s monthly expenses, as well as the costs of operating the rescue facility. Sponsoring a dog costs between 1,500 and 2,000 Egyptian pounds, or about $30 to $40 a month. Currently, 20 of her 74 dogs have sponsors, all of them Egyptian.

While she has not adopted out any Baladi dogs to responsible owners yet, the sponsors are increasing.

“Lately, our culture has been changing and more people than ever are adopting Baladi dogs. There’s more awareness about the positive traits,” she says.

Some Egyptians also adopt dogs they encounter in their neighborhoods.

Omar Hamaki, a Cairo resident, took in a female Baladi dog named Diva, whom he first fed as a street dog. “She gave me all the love and attention I could have ever imagined,” says Hamaki. (Meet the people trying to help Morocco's three million stray dogs.)

Mina Medhat, who adopted Shiva as a puppy in 2021, says the dog is a vital part of the family. “Shiva treats everybody in our family in a different manner, yet it is the manner that fits every one of us,” Medhat says.

Medhat also stressed that adopting Baladi dogs is not for everybody, as some animals still show signs of trauma, such as anxiety around people.

On the other hand, Hossam Hosny, a proud parent of Leil, a Baladi dog, has noticed differences between Leil and a golden retriever he fostered, particularly in Leil’s ability to stay calm in stressful situations.

“Baladi dogs are smarter due to their experience on the streets,” Hosny says.

While Baladi dogs have a long way to go to reach the status of Egyptian canines so many centuries ago, their burgeoning popularity may someday put them back on a pedestal.