Why does Pantone have a color of the year? It started with ... birds

This is the year of mocha mousse, according to Pantone. The company's annual color craze originates in part from the work of a 19th-century ornithologist who described the dizzying array of bird colors.

Pantone has announced its color of the year, mocha mousse, which highlights the hue’s link with comfort and indulgence. The shade “extends our perceptions of the browns from being humble and grounded to embrace aspirational and luxe,” Pantone’s executive director Leatrice Eiseman said along with the announcement.

As it does every year, the color not only represents design trends but also the current culture. While Pantone’s trend-setting world of digital design seems as distant as it could be from dusty museum shelves of century-old bird specimens, the two topics are closer than you might think.

That’s because the company’s giant color compendiums originate at least in part from ornithology and natural history.

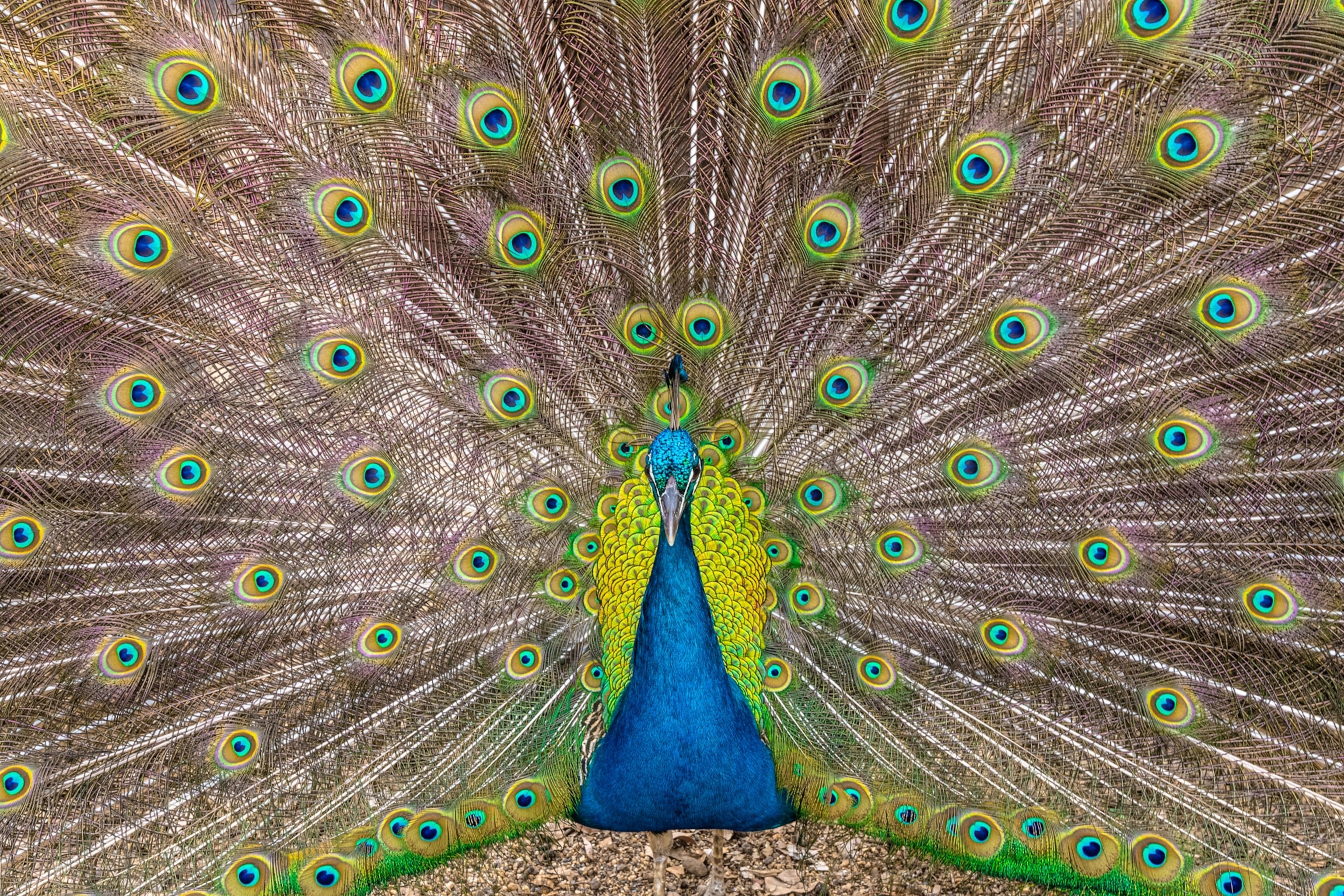

Robert Ridgway, an ornithologist and artist at the Smithsonian's United States National Museum from 1886 to 1929, was tasked with describing the country’s diverse bird life. To do that, he needed first to accurately describe birds’ color, from the vibrant reddish orange of an American robin’s breast to the wine reds of the purple finch. That’s harder than it might sound, as a color can appear different from moment to moment based on ambient light and other nearby shades. (Read: Tracing the roots of beautiful bird hues.)

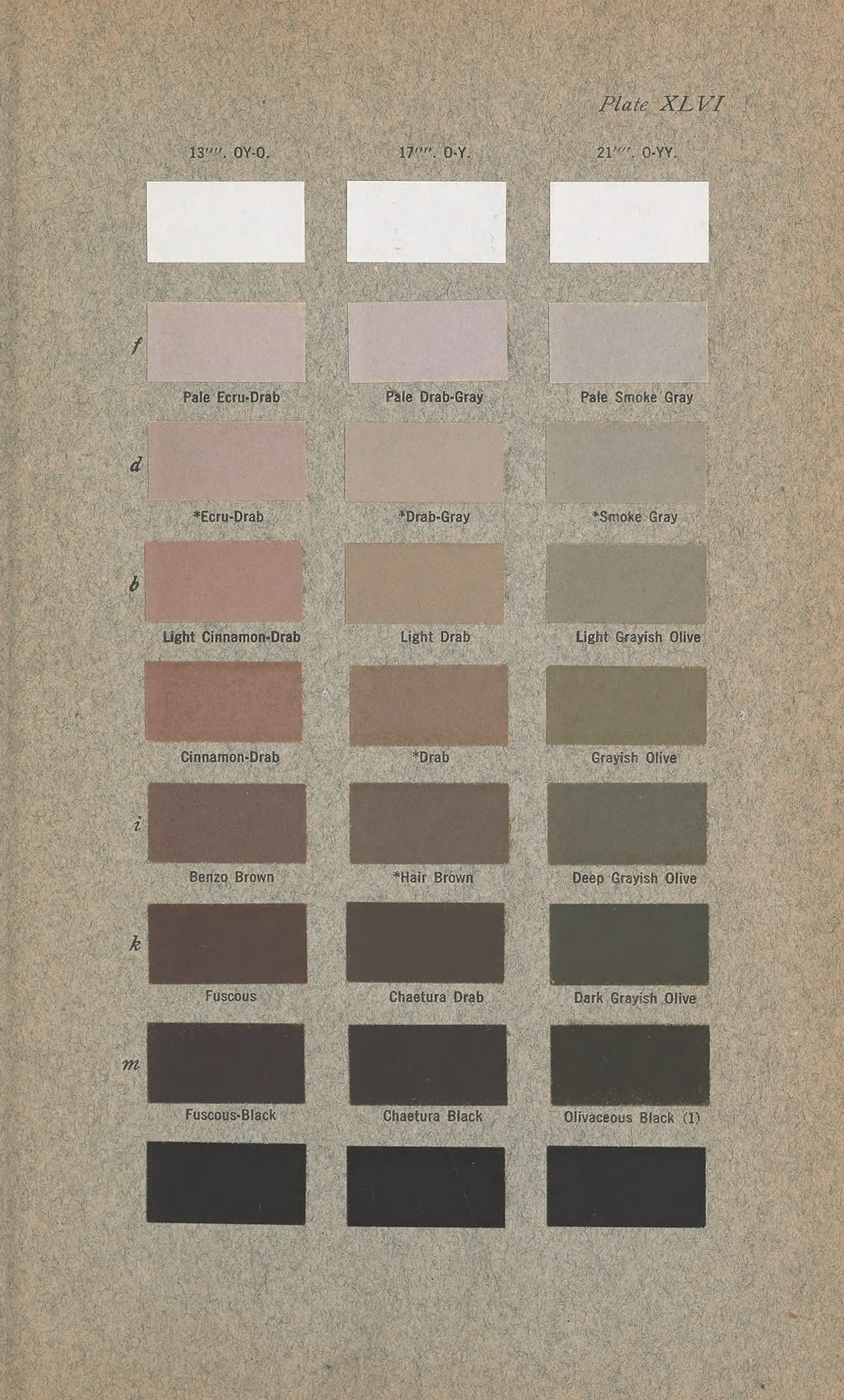

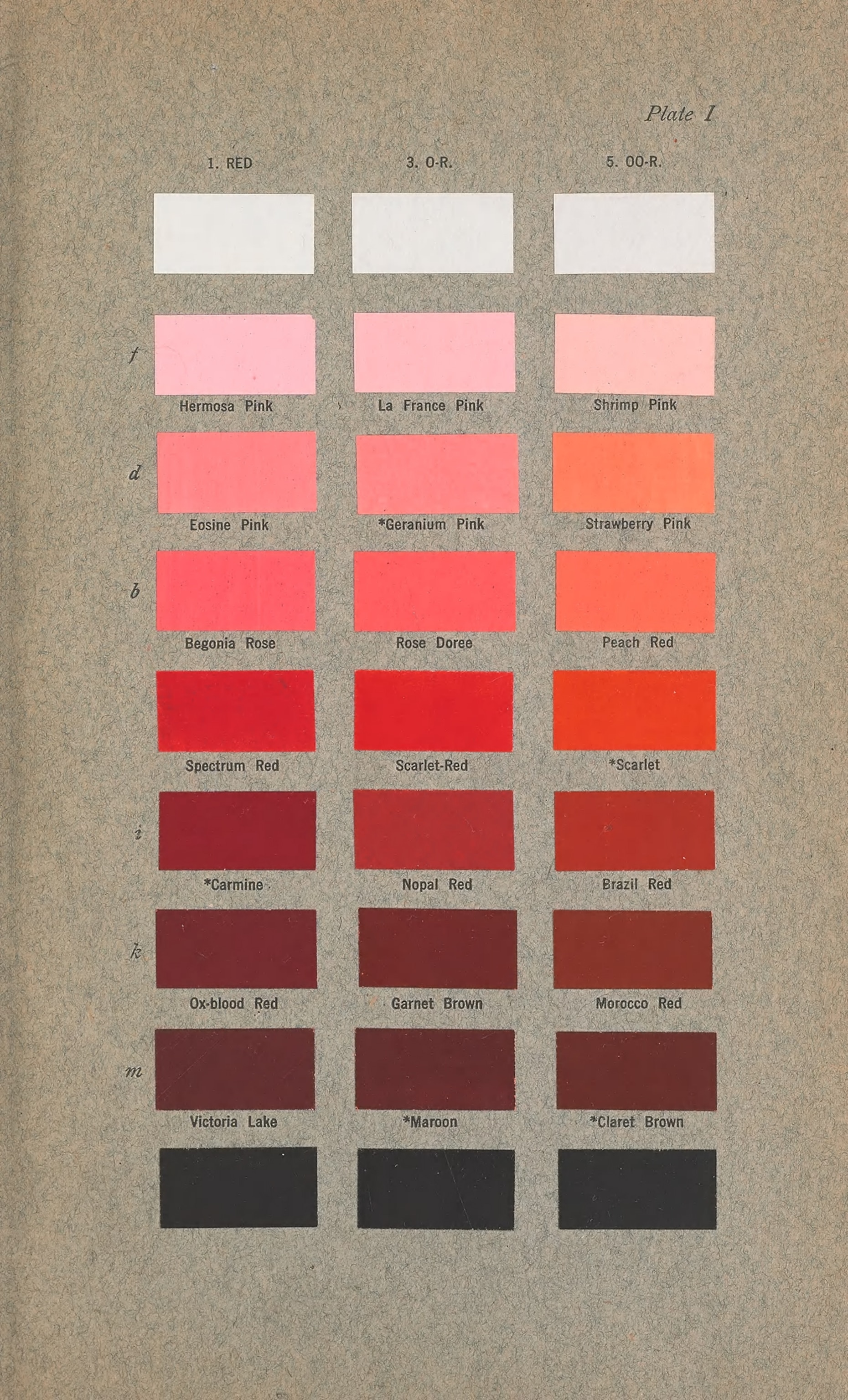

To solve this problem, Ridgway published two dictionaries of over a thousand different colors, from mustard gold to peacock blue, featuring page after page of hand-painted color swatches. These humble beginnings—Ridgway self-published the latter volume at his own expense—ultimately gave rise to the Pantone Color Institute in the 1960s.

“There wasn't this common vocabulary about color until Ridgway created it,” says Brian Ellis, president of the Illinois Audubon Society and portrayer of Ridgway in living history skits. “He had a very specific need, but what he created quickly found a very broad use.”

True colors

For both amateur birders and ornithologists alike, color plays a major role in species identification, says Kevin McGowan, senior course developer and instructor at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in Ithaca, New York.

But simply describing a bird as “blue” isn’t enough. Blue jays, eastern bluebirds, and indigo buntings are all blue birds, but the rich azure of an indigo bunting is nothing like the softer, sky blue of a jay.

“It is extremely difficult to describe the subtle color differences,” he says. Due to innate biological variations, “we may, in fact, be seeing something different.”

Ridgway devoted much of his time to describing the diversity of North American birds, ultimately naming and describing over a thousand species, according to Ellis.

Ridgway sketched and painted many of these birds with his wife, Julia Ridgway, with a skill that rivaled John James Audubon.

While color dictionaries had existed for centuries before Ridgway’s life, they were far from comprehensive, nor were they designed for naturalists. (Read: These stunning photos of feathers will tickle your fancy.)

The late 1800s also saw the advent of chemical dyes. Derived from coal tar, these chemical dyes did not have the batch-to-batch variability of botanical dyes upon which the world had historically relied, opening up a whole new world of color to Ridgway and others, Ellis says.

An indispensable resource

In Ridgway’s 1886 book, A Nomenclature of Colors for Naturalists, he and Julia painted entire pages with an individual color, cutting them up into small swatches to be glued into each book. This ensured that, say, the olive green in each volume was identical. Their brush strokes can be seen in the book’s 186 color plates.

“In their handmade books, every copy was exactly to standard,” Ellis says.

Though this was an accomplishment, Ridgway still felt the volume inadequate. So he struck out on his own to publish a larger volume. In this version, the Ridgways organized each page in a spectrum of shades, with pure white at the top left and black at the bottom right. Arrayed in between was a range of hue and tone, enabling painters and naturalists alike to precisely match colors.

The resulting Color Standards and Color Nomenclature, published in 1912, was an immediate hit, selling out several printing runs. As he hoped, naturalists found the guide indispensable, as did designers, stamp collectors, and food colorists.

The Ridgways’ color guides are still fundamental to our understanding of the diversity of life, says Sarah Luttrell, a research assistant in the Feather Identification Lab at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History.

“Humans are really visual creatures. Color is the thing that strikes us first,” she says.

Ridgway for the modern age

In the late 1950s, printers and advertisers were facing a similar color quandary as Ridgway had, only on a larger scale. Manufacturers needed to ensure that the colors they used were both distinct from competitors and consistent across time and space.

Recognizing an unmet need, Lawrence Herbert bought out the printing company where he worked in 1962 and created Pantone. The company’s Pantone Matching System was essentially an industrial-scaled version of color systems like those Ridgway’s 1912 volume and similar works by color aficionados like Albert Munsell. The color dictionaries have also gone digital to reproduce colors on computer screens.

The selection of a Color of the Year may not have resounding implications for Luttrell in the Feather Identification Lab, yet it remains a key part of her work in identifying species. (See National Geographic's favorite bird pictures.)

“There's lots of things still to learn about color and how it matters for the animal. The better we can measure it, the more we can learn,” Luttrell says.