Dazzling photos show horseshoe crabs thriving in protected area

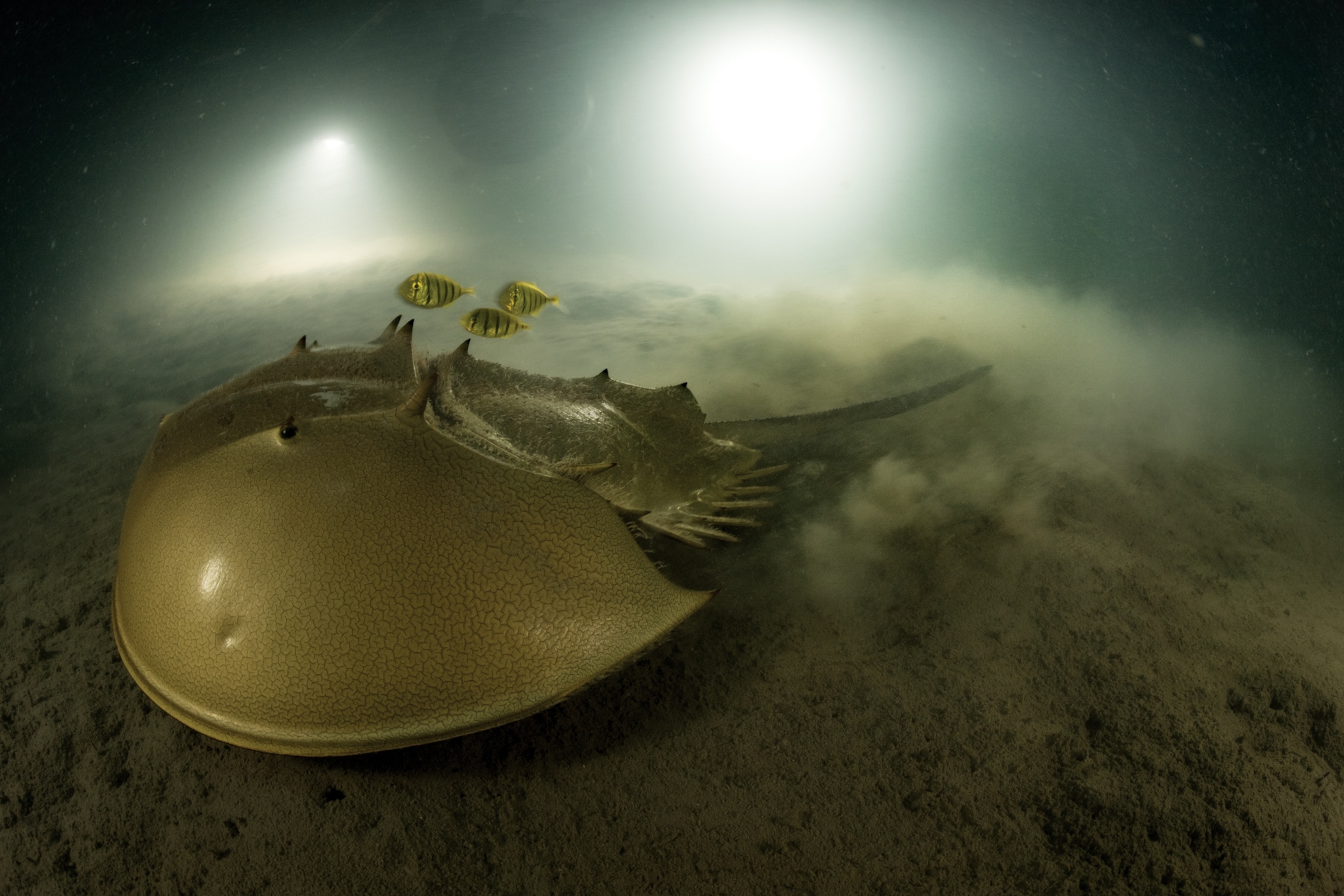

In the Philippines, the tri-spine horseshoe crab has made a home and other species are returning too.

Horseshoe crabs are built to last. With spiky tails, shells shaped like combat helmets, and sharp pincers at the end of eight of their 10 legs, these ancient invertebrates have been scuttling along the ocean floor relatively unchanged for some 450 million years.

They managed to survive the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. Surviving humans may prove more difficult. Like many marine animals, horseshoe crabs are overfished for food and bait, and coastal development has destroyed spawning sites. But they also are collected en masse for their blue blood, which contains a rare clotting agent critical for the development of safe vaccines. The blood may be lifesaving for humans, but its harvest often kills the animals—particularly in much of Asia, where they are drained of all their blood rather than just a portion of it.

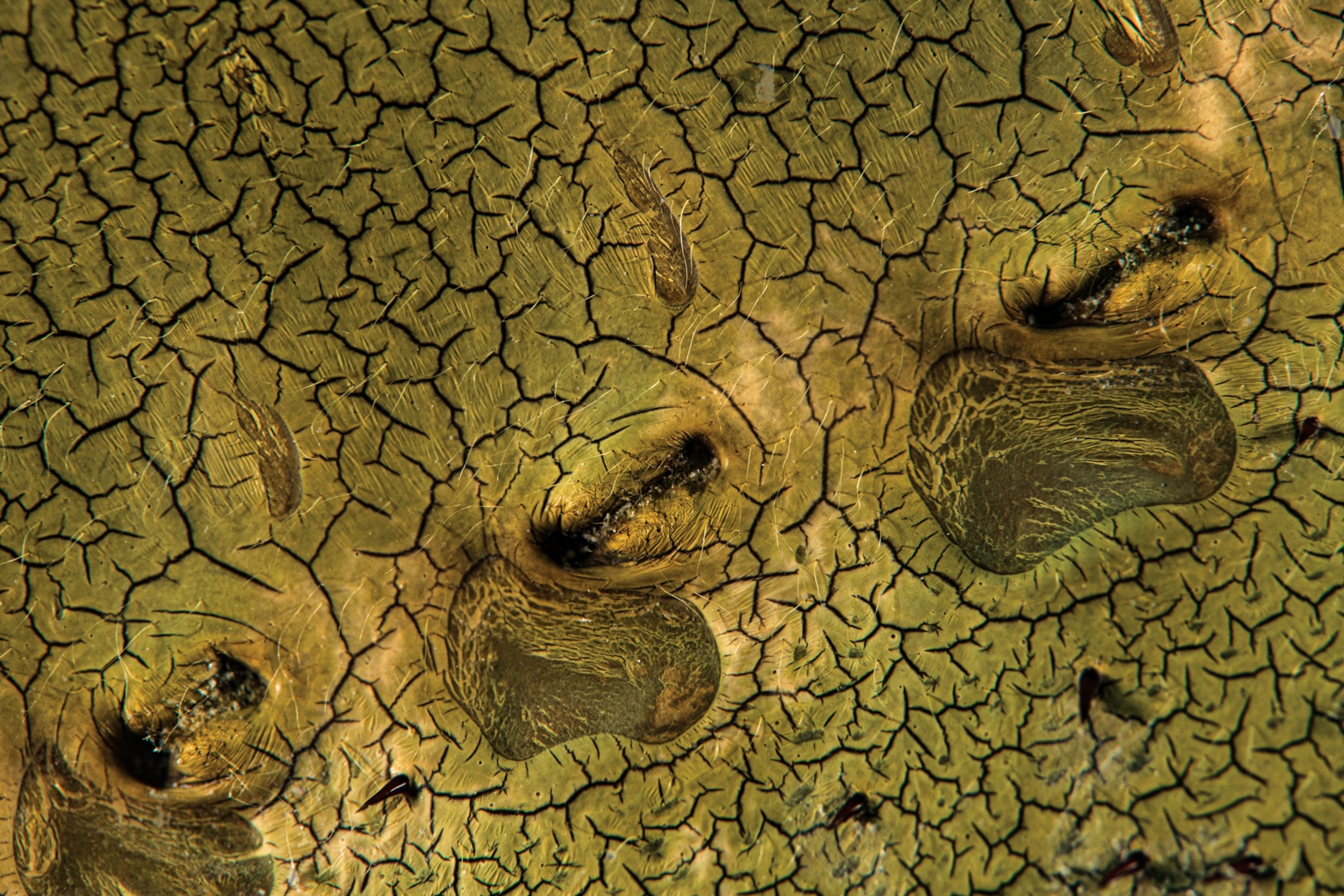

Tri-spine horseshoe crabs have lost more than half their population in the past 60 years. But on the Philippine islet of Pangatalan, the species is an unexpected symbol of resilience. For years the island’s 11 acres were degraded: trees cut down for timber, mangroves burned for charcoal, and coral reefs overfished with dynamite and cyanide. By 2011 these horseshoe crabs, about 15 inches long, were among the biggest creatures left.

Now a marine protected area, Pangatalan is starting to thrive again. Efforts to restore its reefs and plant thousands of trees have led many animals to return, including rare giant groupers that grow to some eight feet long.

(For Atlantic horseshoe crabs, love is a battlefield)

Horseshoe crabs may not be as charismatic as elephants or pandas, but perhaps they’ll inspire people to care more about wildlife. Appreciation for horseshoe crabs has grown thanks to their role in COVID-19 vaccine development. Conservationists hope that regard will translate to stronger habitat protections and wider adoption of a synthetic alternative to crab blood—saving horseshoe crabs just as they’ve helped save us.

This story appears in the August 2022 issue of National Geographic magazine.