These ants are saving our forests—by spraying acid everywhere

The engineering and defensive skills of red wood ants help the endangered species transcend its small stature in the natural world.

Wildlife photographer Ingo Arndt discovered his first enormous ant mound as a child exploring the forest with his father near their home in Germany almost 50 years ago. They were bird-watching and came around a bend in a densely wooded area when there it was: a five-foot-tall mound, jutting upward like a large stalagmite. The mound was covered with a thick layer of spruce needles and throngs of tiny red ants.

Arndt wanted to investigate more closely, but a very particular smell suggested he rethink that impulse. The air felt thick and pungent, stinging his nostrils like vinegar. “All my life,” he says, “I could remember the smell.”

As an adult, Arndt has spent much of his career traveling to photograph animals like the pumas of Patagonia and kangaroos in Australia. Several years ago, he moved to the German countryside with his wife. While hiking through the region’s pine forests, the surroundings rekindled his fascination with the mounds and their armies of ultrasmall engineers. How did insects roughly a quarter of an inch long build such huge structures? And why did they emanate that astringent odor?

(These ants are the first known animals to use moonlight to find their way home.)

Arndt now had the tools and experience to seek answers to his questions. Outfitted with a high-resolution camera and macro lenses that allow you to focus on small objects up close, he began photographing the mounds and sharing his imagery with researchers for a scientific perspective. It turned out the mound makers were indeed special. They were red wood ants—scientifically classified as a group within the genus Formica—one of the smallest of all so-called keystone species.

Among conservationists, keystone species such as elephants and sharks are watched closely because their behaviors affect so many aspects of their ecosystem that if they disappeared, it would struggle to adapt. Red wood ants are typically found in Eurasia’s temperate and boreal forests. But in recent decades, more nests have been disappearing as the forests have fallen victim to logging, urbanization, and wildfires, as well as drought and higher temperatures that have become more frequent with climate change. This has led several countries across the ants’ range, including Germany, to designate them as a protected species by law.

Today Arndt’s photo quest has taken on new meaning. His images, which he’s been producing for the past two years, put on display these creatures’ fascinating ability to forge a multitude of symbiotic relationships across a variety of plant and animal species. In doing so, he’s revealed the wonders of a hidden insect world.

The massive NESTS consist of two parts, one aboveground and one below, which red wood ants create by both burrowing into the earth and gathering needles, leaves, bark, and twigs. As they rise, each mound gains new entrances and corridors, supporting anywhere from 30,000 to upwards of 16 million insects, the largest aboveground nests of any ant species in the world.

To learn more about this concealed society, Arndt enlisted the help of entomologist Bernhard Seifert, of the Senckenberg Natural History Museum’s research institute in Frankfurt, and zoologist Jürgen Tautz, professor emeritus at the Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg. The researchers helped explain how Arndt’s images showed the ants directing life within the forest in surprising ways.

(These ants perform life-saving amputations on each other.)

For instance, the ants generate formic acid in a venom gland at the rear of their abdomen. As they build a nest, the insects will gather tree resin, which has been shown to possess antimicrobial properties, and spray it with their acid, which has its own antimicrobial properties. The result is a more potent agent that the ants place throughout the structure to fight against bacterial and fungal pathogens.

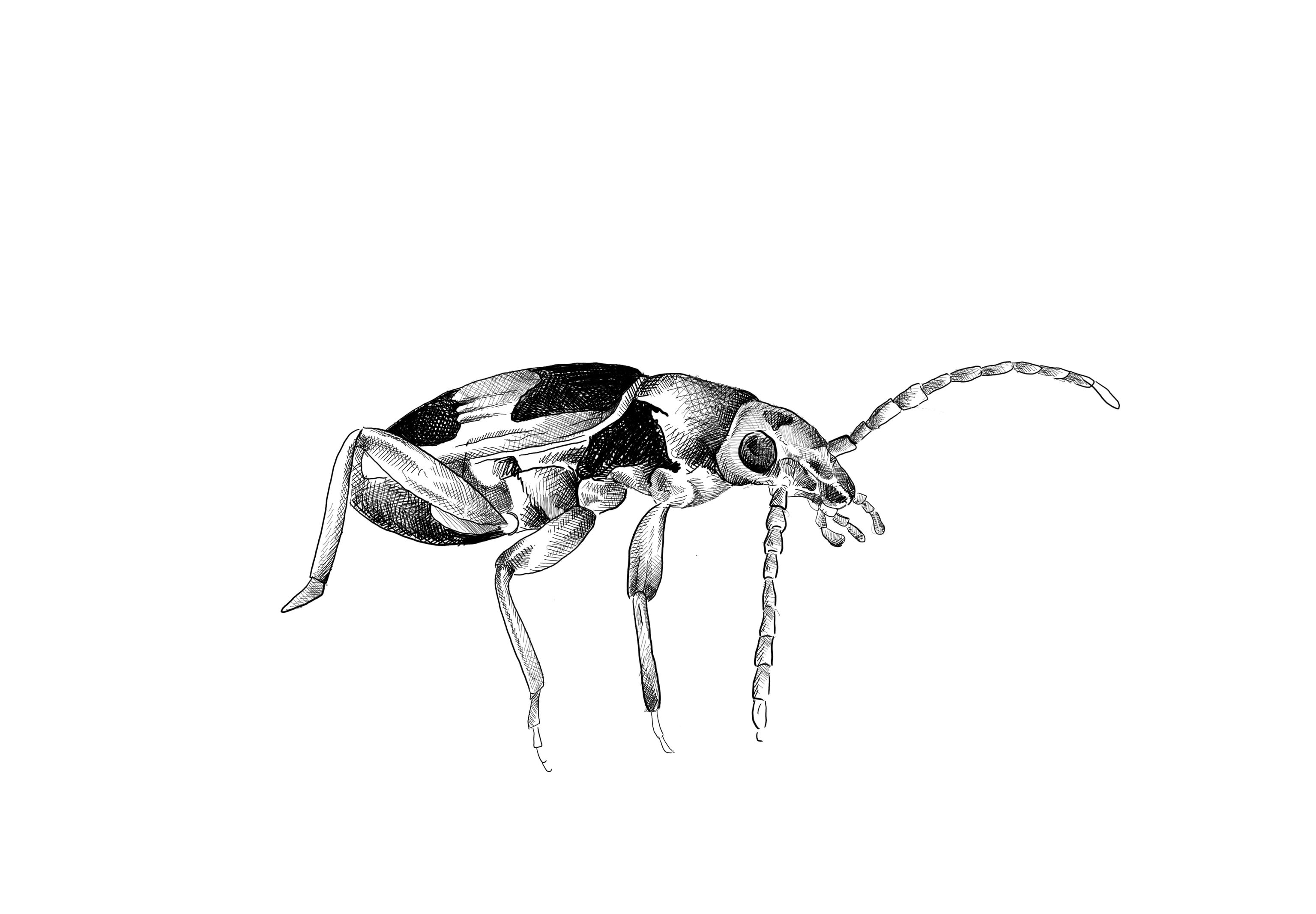

Formic acid also powers the species’ pest-control role. The fluid can be weaponized to take down other insects, like wood-boring beetles, one of the most destructive vermin in spruce forests. The fighting tactic, Seifert explains, involves “biting them and then spraying formic acid into the wounds.” Reducing the number of beetles that weaken and destroy trees improves conditions for aphids living in them. The ants “milk” the aphids to excrete honeydew, which becomes their primary food source.

Using camera traps, Arndt also captured larger animals lining up to get sprayed voluntarily. A rare image shows a Eurasian jay landing on top of a mound and calmly flattening out its tail to allow the ants to crawl up and attack. “The ants spray the jays as an enemy,” says Tautz. While the birds appear unharmed, the toxin is powerful enough to disperse or kill parasites, such as mites and lice, that they carry. For many bird species, this behavior helps them stay healthy too.

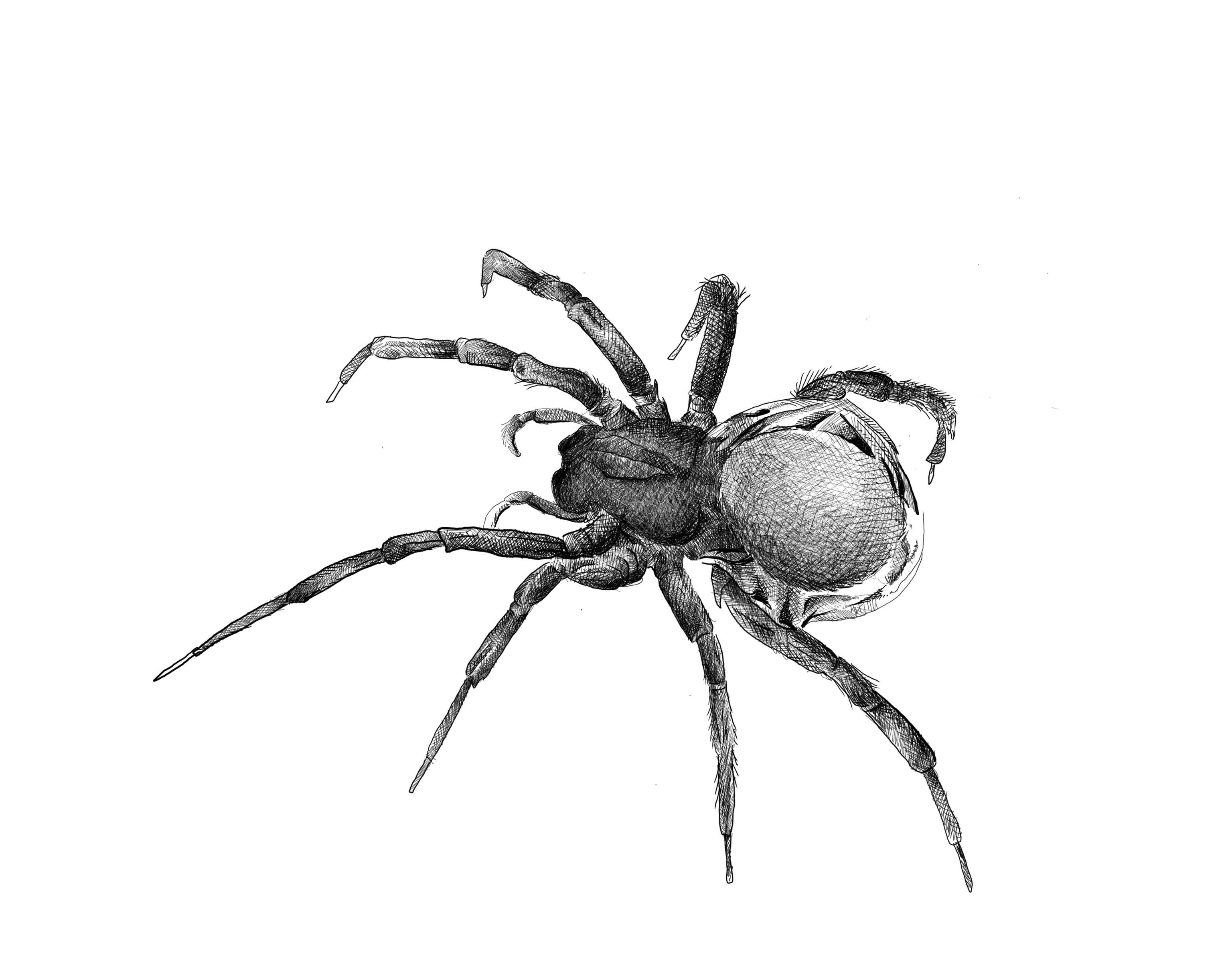

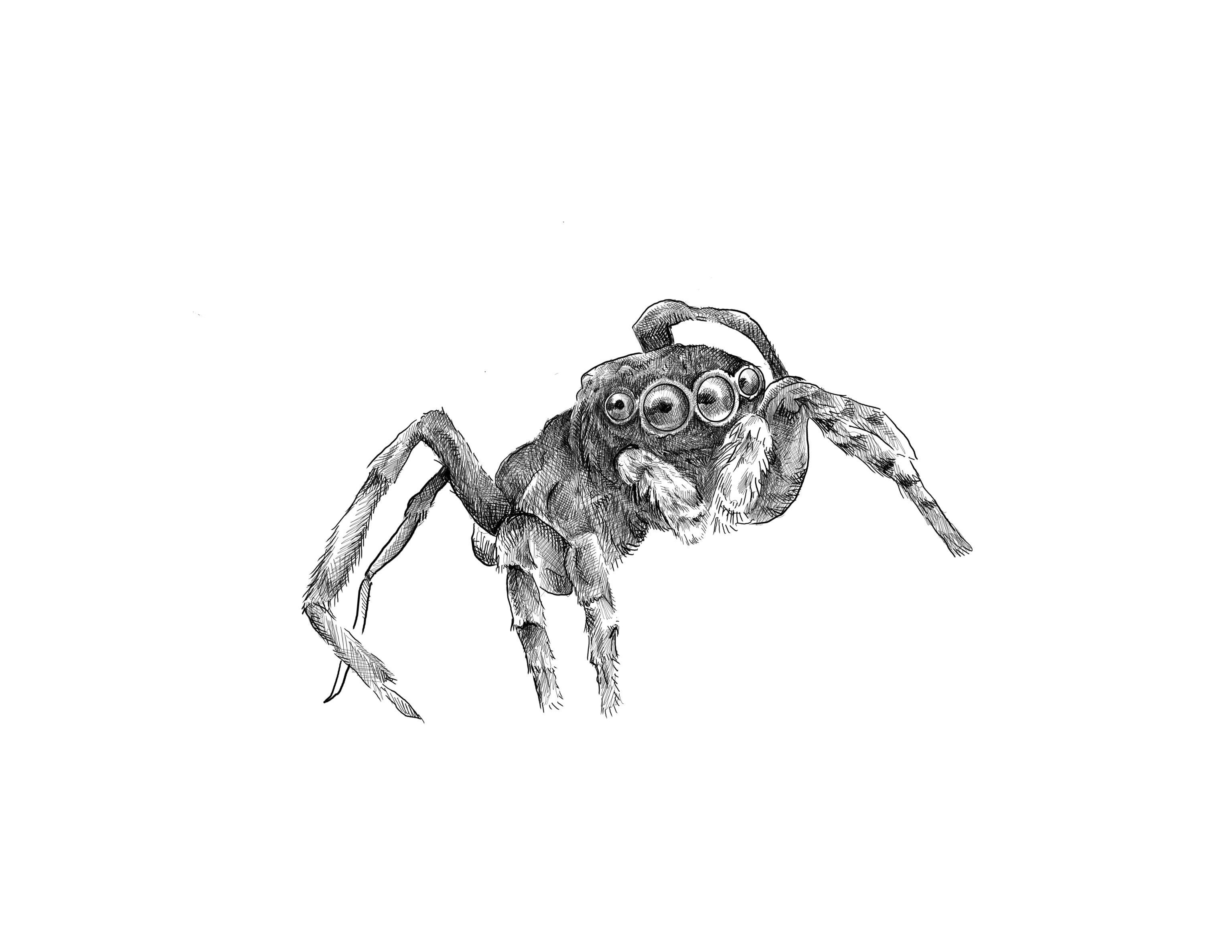

Some uninvited guests that are willing to reek alongside the community have gained more benefits. As social insects, ants organize colonies and form complex societies, but they also cohabitate with a wide variety of species, including mites, spiders, and flies, within their nests. One trick is that some of these interlopers may have grown up already doused in a familiar scent.

If a leaf beetle drops its eggs on or near the mound, the workers may inadvertently bring the eggs into the nest while collecting materials. “The larvae actually live inside it,” Arndt explains. The eggs, then the larvae, and eventually the pupae all smell like the nest. That’s how they elude their hosts’ detection and exploit the shelter to survive. In one study, researchers confirmed that, on average, more than a dozen different species can be found within a single mound.

Arndt’s project highlights the strange and amazing ways these often overlooked creatures are influencing the action around them. While he did his best to avoid disrupting the protected species, the ants at times had other ideas and they’d hitch a ride back with him.

“I’ll be out at dinner, and they show up and walk over my pants,” he says, laughing at the memory. “But I always try and bring everybody back to the nest.” The forest needs their collective power.

(These ant 'portraits' reveal how diverse and beautiful these insects are.)

Secrets to living super small

Eric Alt is a California-based writer and editor specializing in culture, technology, history, and science.

Ingo Arndt, a German wildlife photographer, got bitten on assignment for this story and was sprayed with their astringent repellent, “I love these little, smart, social creatures anyway,” he says.