This worm-like parasite is killing off Florida’s native snakes

Snake lungworm disease, which infects at least 19 snake species, is poised to spread throughout the southeastern U.S.

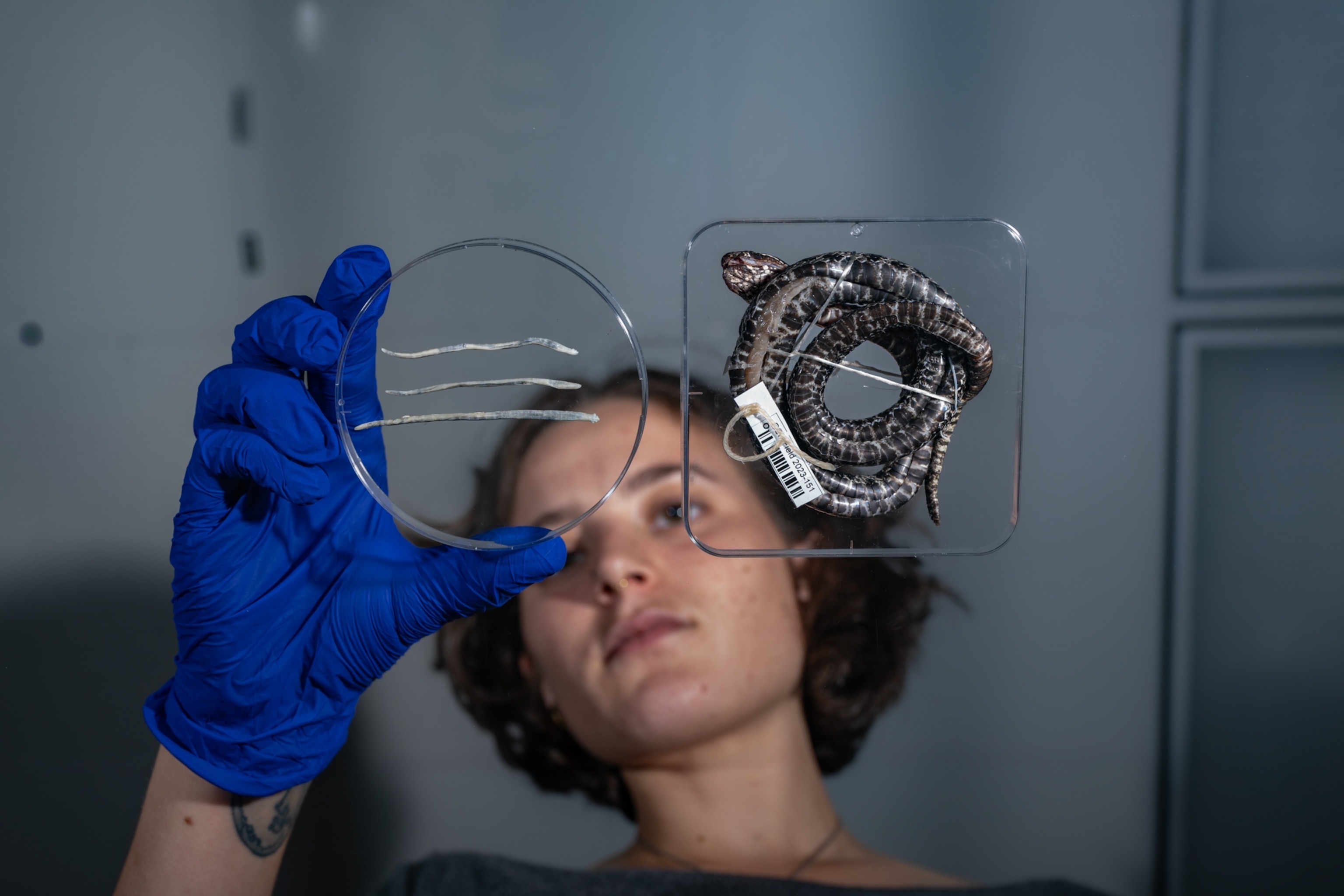

In 2023, Jenna Palmisano picked up a sick dusky pygmy rattlesnake among the fallen palm fronds of central Florida.

“The snake we found was flipped on her back with her belly up, and she passed away in our hands,” says Palmisano, a Ph.D. student in biology at the University of Central Florida.

A ghastly disease is making its way through the Sunshine State's underbrush, leaving native snakes dead with a worm-like parasite protruding from their mouths.

The long, whitish parasite, Raillietiella orientalis, which vaguely resembles a bean sprout, feeds on a snake’s lungs until the animal dies.

Melissa Miller, an invasion ecologist affiliated with the University of Florida, first discovered a native snake infected with R. orientalis in 2012 in southern Florida, and later traced the disease’s origins to the invasive Burmese python, which arrived in the state from Asia in the mid-1990s. Since then, the parasite has infected at least 19 of Florida’s native 46 species, from banded water snakes to black racers. (Read about another fatal disease spreading among North American snakes.)

Now, a study published in 2023 shows snake lungworm disease is moving quickly throughout central and northern Florida, and is likely to expand into other southeastern U.S. states. The study relied on data collected by Snake Lungworm Alliance and Monitoring (SLAM), an organization established by study co-author Palmisano, with over a hundred collaborators from nonprofits, academics, state agencies, and citizen scientists. Though the parasites are scientifically called tongueworms, the term "lungworm" is more commonly used throughout the southeastern U.S.

“There's every reason to think the rapid spread will continue,” says study co-author Terry Farrell, a biology professor at Stetson University in DeLand, Florida. “The parasite can survive frost, because its host will protect them from climate extremes.”

An ideal setting for lungworm

Snake lungworm disease begins when a cockroach eats feces of an already infected snake. Eggs hatch into larvae inside the cockroach, which is then eaten by various intermediate hosts, such as lizards, frogs, and small mammals.

When these intermediate hosts fall prey to snakes, they transfer the parasite to their final host, where the larvae makes a beeline for the lungs.

Adult parasites, which feed on blood, and can grow up to nearly four inches long inside some snakes, causing inflammation and lung lesions, pneumonia, or sepsis. Infected snakes lose so much energy fighting the parasite that they may stop feeding altogether and starve to death. (Learn about a mysterious condition that caused Florida fish to spin in circles and die.)

To make matters worse, Florida’s verdant, swampy landscapes provide a multitude of intermediate hosts, which allow the parasite to move around more freely.

What’s more, the state’s role as a global epicenter of the reptile and amphibian pet trade benefits the parasite. Sellers who legally capture wild snakes have no way of knowing if they are infected and can sell them to buyers. Other reptiles popular in the pet trade, such as tegus or tokay geckos, can also host these parasites, though it’s unknown how their health is affected.

“R. orientalis is a generalist parasite, which makes it even scarier,” says Palmisano. “It has unknown potential to spread to people's pets.”

Cottonmouths show resilience

Other factors make the disease hard to research and control. For one, because snakes live mostly hidden from people, “we tend to underestimate the importance of this issue,” Farrell says.

U.S. snakes also have no built-in defenses to fight the foreign parasite, making them more vulnerable. Because Burmese pythons evolved alongside snake lungworm, they can more easily survive infections. (Read about the largest python ever caught in Florida.)

It’s possible that some infected snakes could be saved if captured and treated by experts, but that isn’t a realistic solution.

“it’s impossible to go out, catch all the wild snakes in an area, treat them, and fix them, because you also would have to treat all the frogs, lizards, and roaches,” says Farrell.

Yet there is some reason for hope. Miller’s research shows that while several snake species are declining, the Florida cottonmouth, a heavily infected species, are not.

“Preliminary results suggest that some native snake species may be more resilient to R. orientalis infection than others,” she said in an email. It’s possible that the parasite is not as detrimental to the cottonmouth’s immune system, for instance.

“So that gives hope that some native snake species may be able to mitigate impacts from infection.”