The epic journey of Canada’s last (and only) reindeer

Their unusual story began about a hundred years ago. Now, as they head to the high north, an ambitious new chapter is being written.

Beneath the glow of the morning sun, thousands of reindeer plod across the frozen far reaches of northwestern Canada. In the slow-moving scrum, the animals’ bodies almost disappear under a cloud of vapor as warm breath collides with cold air. A forest of antlers seems to dance in the mist. Glimpsed from afar, the migrating herd looks like one long, sinuous streak of brown painted across the snow-white canvas of an Arctic landscape.

In the distance are four Inuvialuit herders on snowmobiles, armed with rifles and keeping watch. They are alert, attuned to the rhythm of hooves falling on frozen earth, and on this crisp morning their job is to escort the reindeer to their calving grounds—but in a grander sense, they are also helping to write a new legacy for this storied herd.

“They’re really smart animals,” said Douglas Esagok, whose seven winters working with the reindeer make him among the most experienced of the Indigenous herders. “I’m always talking to them when I’m moving them. It kind of calms them down, when they recognize my voice or the sound of my snow machine.”

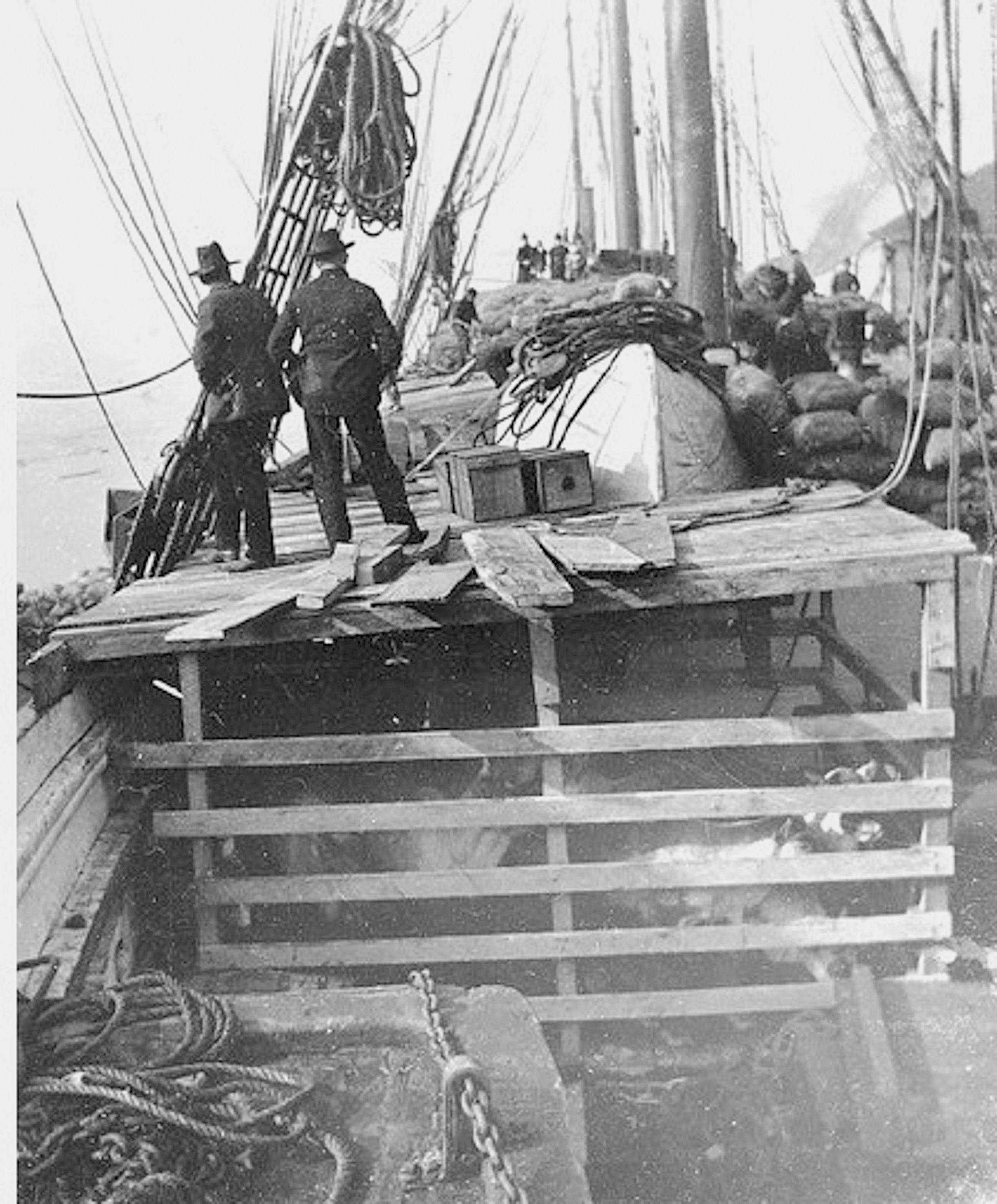

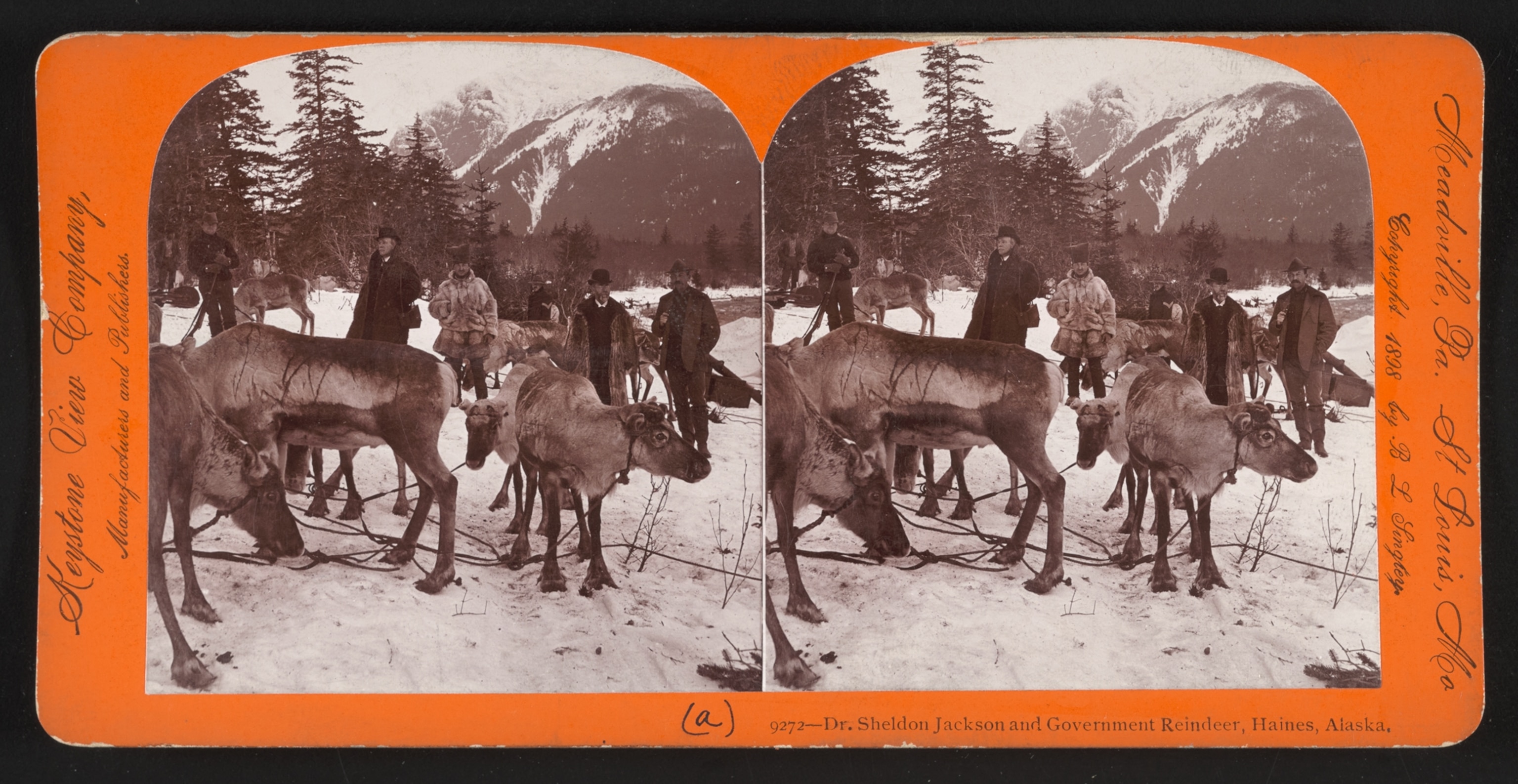

As Canada’s last free-ranging reindeer herd drives forward, just north of the Arctic Circle, the animals carry with them a link to a legendary experiment. It began about a hundred years ago, after the number of local caribou that the Inuvialuit long depended on began to decline and a bold plan was hatched to address food scarcity by importing reindeer. (Caribou and reindeer are the same species, but the latter have been domesticated.) Something similar had been tried at the turn of the century in nearby Alaska, when waves of reindeer boarded boats and trains to make improbable journeys from Siberia and Norway to North America. In late 1929, a chunk of what was then a burgeoning Alaska reindeer population—some 3,500 reindeer—set off for Canada under the care of Sami and Inuit herders. The arduous, zigzagging 1,500-mile journey ended up lasting more than five years, marking a difficult beginning to what came to be known as the Canadian Reindeer Project.

(To save caribou, Indigenous people confront difficult choices.)

Now, decades on, a group of Inuvialuit stakeholders is taking the project further into uncharted territory. The herd, which has been cared for with the help of the Inuvialuit but family owned, was formally purchased in 2021 by the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation. Under the watchful eyes of Esagok and his colleagues, the herd has more than doubled, to nearly 6,000 reindeer, making possible an ambitious plan to build a sustainable path to self-reliance for Inuvialuit people living on their ancestral lands.

“The ultimate goal is to have reindeer abundantly available for Inuvialuit—that’s goal number one,” said Brian Wade, director of the Inuvialuit Community Economic Development Organization. “There’s the food security component to this herd, but there’s also job creation and the economic component to it.”

The reindeer’s transfer to Inuvialuit ownership goes beyond an attempt at establishing stability for the future. It also represents a chance for the Inuvialuit people to take control of a herd imported to their homelands by a colonial government. In the 1930s, when the reindeer came to the Northwest Territories, the role they were meant to play in the lives of Inuvialuit people was mostly to replace their ancestral food-gathering customs. The Canadian government had been establishing administrative stations and allowing the creation of trading outposts throughout the region following its acquisition of the Northwest Territories in the late 1800s. The Indigenous population had for centuries subsisted primarily on hunting and fishing, but with caribou in decline, reindeer were imported to address food shortages. This also changed the relationship the Inuvialuit had with the land, as reindeer could be raised as livestock.

“Reindeer are classified as domesticated animals, the same as a cow or a chicken or a pig,” said Wade. “They’ll graze all day and just keep moving slowly and slowly and slowly finding greener pastures.”

In the years before the IRC took control of the herd, the reindeer were owned by an Inuvialuit family—the Binders—whose associations with the reindeer stretch back to their arrival in the Mackenzie Delta. The Binders had grazed the animals and sold reindeer meat but had increasingly struggled, with too few herders, to stave off predators and keep the herd from splintering. As the number of reindeer dipped, the Inuvialuit leaders at the IRC were in the process of recognizing the powerful role that a bolstered reindeer population could play in the community.

(World’s largest reindeer herd targeted by poachers for antler velvet.)

Plenty of Inuvialuit continue to hunt for their food, but it can be a costly and time-intensive effort, and, as any hunter will attest, some seasons are better than others. Over recent decades, many families have moved away from the traditional subsistence model, depending instead on food markets and grocery stores stocked by southern food supply chains. But in 2020, at the outset of the global pandemic, many of those supply chains broke. The IRC, which began to envision a role for the herd in addressing food shortages, could see clearly that the threat was not hypothetical but immediate.

“We’ve been able to really capitalize on the country food that’s abundant in our region but also tie in the reindeer herd so we could alleviate the pressure on the local caribou herd and have the sustainable protein source,” said Wade. The purchase of the herd, he added, was part of a two-pronged plan toward food sovereignty. The other initiative was the opening of the Country Food Processing Plant in the town of Inuvik, where reindeer, among other food sources, could be prepared and then sent off for distribution to families in need.

Before any reindeer could be harvested, though, the herd needed to be nurtured back to full strength. The IRC brought on Esagok and fellow Inuvialuit herder Steve Cockney, Jr., who then spent months reuniting the dispersed reindeer herd.

“One of the main challenges was rounding up all the stray animals that were spread out over a huge area,” said Esagok. Some groups had strayed as far afield as 80 miles, which meant days of travel for Esagok and his partner. These smaller groups of reindeer were vulnerable to wolves and other predators, and while many animals had been lost and others roamed beyond the two herders’ reach, Esagok said, “we brought all of them together—the ones that we were able to locate, anyway.”

Since then, the IRC has hired four additional herders, with the crew pulling two-week-long shifts of four men on and two men off at any given time. As a result of their efforts, the herd’s numbers have swelled up to 6,000—enough for Country Food Processing to start its work with the reindeer.

(As males evolve to have better weapons, females develop bigger brains.)

Last spring, the plant, now staffed by five full-time employees, led its first official harvest, preparing 176 reindeer from the herd as roasts, ground meat, and ribs, among other items, that were then distributed to Inuvialuit community members. The meals provide a crucial source of country food, grown and sourced in the region, allowing Inuvialuit households that may not be able to hunt for themselves a chance to stay connected to the land and to this chapter in the Inuvialuit story.

For Esagok, the opportunity to play such a critical role in this new form of food stability and cultural revitalization has been a crash course in learning by doing. In just seven years, he, Cockney, and their team became the heirs to an Indigenous tradition imported from the other side of the Arctic, where the Sami had long mastered the practice. His responsibility to pass this knowledge on to younger herders was made less daunting, he said, by the fact that the region’s Indigenous hunters already have most of the skills to do the job, given their familiarity with the landscape. “It’s not that hard of a job if you grow up hunting,” he said. “We try to talk to the younger guys and explain things the best we can, but a lot of it is hands-on. You learn by doing it and by watching and observing the animals.” The reindeer teach them too, he said. Often, it feels as if they are the ones leading the way.

(Reindeer munch on hallucinogenic mushrooms, and other wild ways animals get buzzed on nature.)

Katie Orlinsky is a Brooklyn, New York–based photographer and National Geographic Explorer since 2022.

The nonprofit National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, funded Explorer Katie Orlinsky's work. Learn more about the Society’s support of Explorers.