An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

In an excerpt from the new book Secrets of the Octopus, an animal lover offers insight into this “strange, beautiful, curious creature.”

I'd never met anyone like Athena before.

Though she was an adult, she was only about four feet tall. She weighed a mere 40 pounds. And she was unusual in several other respects. She could change color and shape, taste with her skin, drool venom, spit ink, and jet about by squirting water through a siphon on the side of her head. Not to mention pour her baggy, boneless body through an opening the size of an orange. Her head wasn’t even on top of her body, like mine. That spot was occupied by a body part known as the mantle, containing the organs of respiration, digestion, and reproduction. Her head was where you’d expect to find a torso. And her mouth was in her armpit.

Athena was a giant Pacific octopus, an Enteroctopus dofleini.

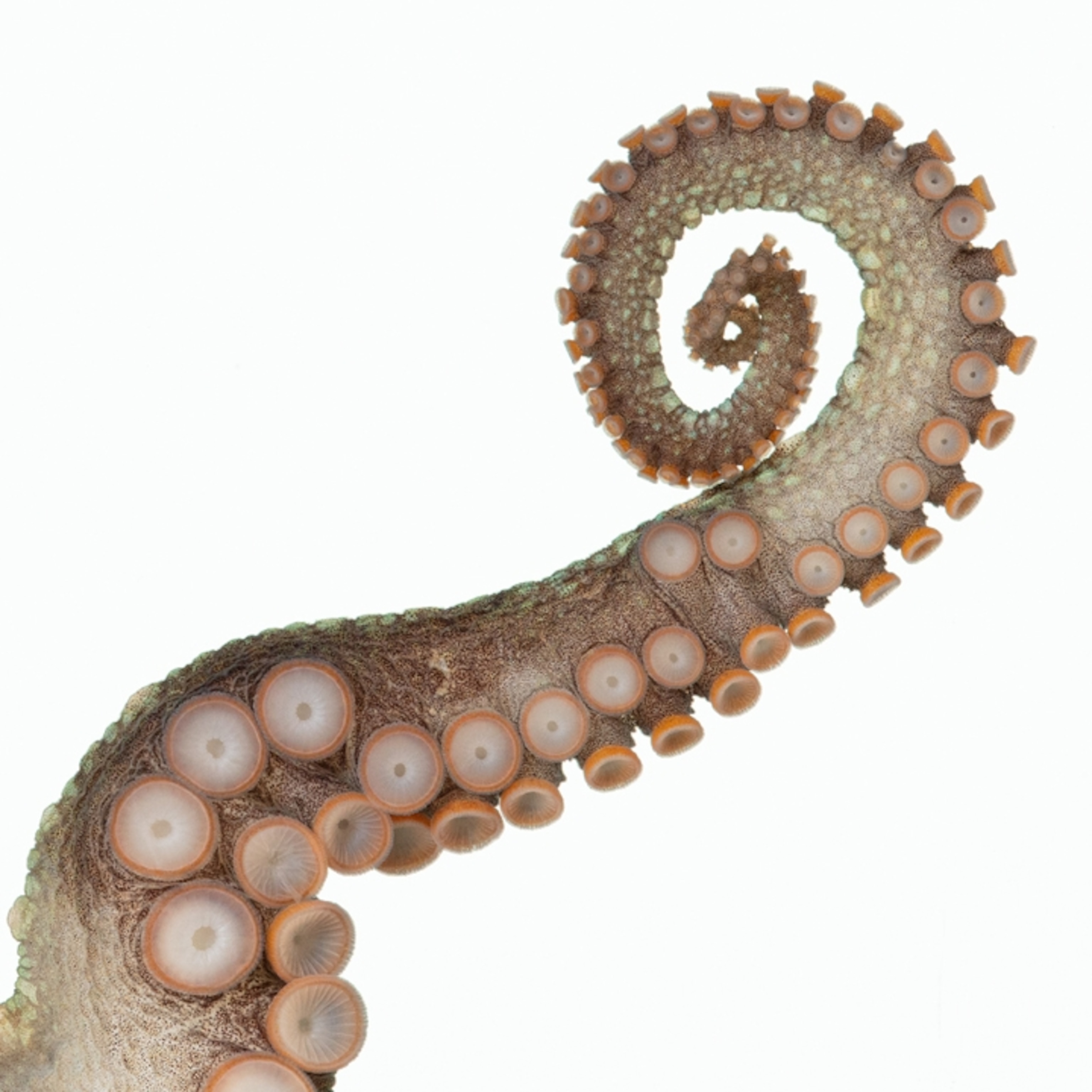

We met at the New England Aquarium in Boston, when senior aquarist Scott Dowd opened the heavy lid to her tank. Standing on a low step stool, I leaned over the water. The octopus changed from a mottled brown to a bright red with excitement as she spilled her liquid body out of her rocky lair. One of her glittering, silver eyes sought mine as her eight arms boiled up to the surface to meet me. With Scott’s permission, I plunged my hands and arms into the numbing, 47°F (8°C) salt water, and I let her engulf my skin with her soft, questing, white suckers. She was both tasting and feeling me at the same time.

Athena didn’t just welcome my company; she allowed me to touch her head. She had not allowed any visitor to do this before. Once we spent time together, as she tasted me and I stroked her, she changed color again. She turned white beneath my touch—the color, I later learned, of an octopus that feels calm.

(When it’s too cold, these octopuses just rewire their brains.)

It was clear to me that we had shared an illuminating exchange. Athena, to my surprise, was just as inquisitive about me as I was about her.

“But aren’t they monsters?” my human friend Jody Simpson asked me the next day as I described my encounter with Athena while we walked our dogs through the woods. Jody is a good friend to many animals. She shares her home with two poodles and a cat. She is an accomplished horseback rider. She loves feeding wild birds. But an octopus? How could you have any kind of communion with an octopus?

Centuries of Western literature have portrayed octopuses as oceangoing demons. “No animal is more savage in causing the death of a man in the water,” wrote Roman philosopher and commander Pliny the Elder around A.D. 77, “for it struggles with him by coiling round him and swallows him with its sucker cups and drags him asunder.” Because they are so different from us, because some species can grow so large, and because of their enormous strength (a single large sucker on a giant Pacific can lift more than 35 pounds, and the animal has 1,600 or more of them), octopuses can frighten and confuse humans—or at least those humans who don’t get a chance to know one.

(A marine biologist demystifies what humans know about octopuses.)

But I was mesmerized by Athena’s otherness. According to almost every basic classification of animal life, she and I were opposites. She was a protostome—developing as an embryo mouth first. I am a deuterostome, developing back end first. She was an invertebrate, without bones. I am a vertebrate, scaffolded with a bony skeleton. She lived in water, I on land. She breathed water. I breathe air. The last time her kind and mine had shared a common ancestor, half a billion years ago, everybody was a tube.

Yet I was also struck by an unexpected sameness. Despite the yawning gap in our taxonomic classifications, it seemed possible that we could have a meeting of the minds. Perhaps we could even be friends.

Equipped with hydrostatic muscles, more like those in our tongues than our biceps, an octopus of her size can, by some calculations, resist a pull 100 times her own weight. That would be 4,000 pounds. I weigh 125. But again, I was not afraid. I felt no malice on her part. Her pull was insistent but gentle. I didn’t worry she wanted to eat me. I was comfortably aware that her beak, located in her armpit, and its adjacent venom glands were nowhere near the parts of the arms that were pulling on mine. Her tenacious tug was no threat. Instead, it was an invitation—one I was honored to accept.

And so this strange, beautiful, curious creature did pull me into her world—a world I explored for years after her death, and am exploring still. Octopuses, alas, do not live long. Giant Pacifics survive only three to five years, and Athena was already old for an octopus when I met her. But over the course of the next three years, I got to know her successors at the aquarium, Octavia, Kali, and Karma, quite well. I visited every week to watch and feed and stroke and play with them.

While all the octopuses I came to know were playful and intelligent, each displayed a distinct personality. When I first wrote of my friendships in a book published in 2015, its title, The Soul of an Octopus, gave some readers pause. How can an octopus have a soul? (Many scientists and philosophers don’t believe in souls; some believe humans don’t even possess consciousness—that it’s just a made-up concept to help us handle the pointlessness of existence.) Octopuses are mollusks, relatives of brainless clams. Surely, some said, suggesting an octopus might have a soul, or a personality, or thoughts or memories or emotions, was simply a product of a misguided propensity to wrongly attribute “human” feelings to nonhuman creatures, like a child pretends that a doll is really alive.

But the attitude that animals are automatons without thoughts or feelings is an idea behavioral scientists increasingly recognize as being as outdated as Pliny’s Naturalis Historia. Jane Goodall’s discoveries that chimps are smart enough to fashion tools, and their personalities distinctive enough for individuals to merit names, trashed the notion that humans alone possess mental experience. Science has since accumulated masses of data that support what many of us knew all along: that animals, from elephants and dolphins to fruit flies and cuttlefish, think, feel, and know. Even—and perhaps especially—octopuses.

These creatures are revealing a totally different path from our own that leads to advanced intelligence. If we follow that path, it may lead us further still, bringing us closer to understanding more secrets, including the shared experience of what it means to think, to feel, and to know.

Secrets of the Octopus, a National Geographic book, is available now wherever books are sold.

Researching articles, scripts, and books, Sy Montgomery has been to the Amazon, Borneo, and Papua New Guinea. Her bestseller The Soul of an Octopus was a National Book Award finalist, and her book Secrets of the Octopus pairs with a new Nat Geo TV series of the same name.

An Explorer since 2018, David Liittschwager has made seven books of photography and dozens of museum exhibitions on natural history. This month’s article on octopuses is his 18th for the magazine.