$1,500 for 'naturally refined' coffee? Here's what that phrase really means.

These high-end beans are removed from the dung of civets, elephants, and birds—but little is known about the living conditions and treatment of some of these captive animals.

Fancy a cup of coffee with beans plucked from an elephant’s poop? That’s the promise of one of the world’s current priciest coffee options. Sold in two-serving packets for about $150, the brew’s served at luxury hotels and to VIP clients. A small amount is also sold online.

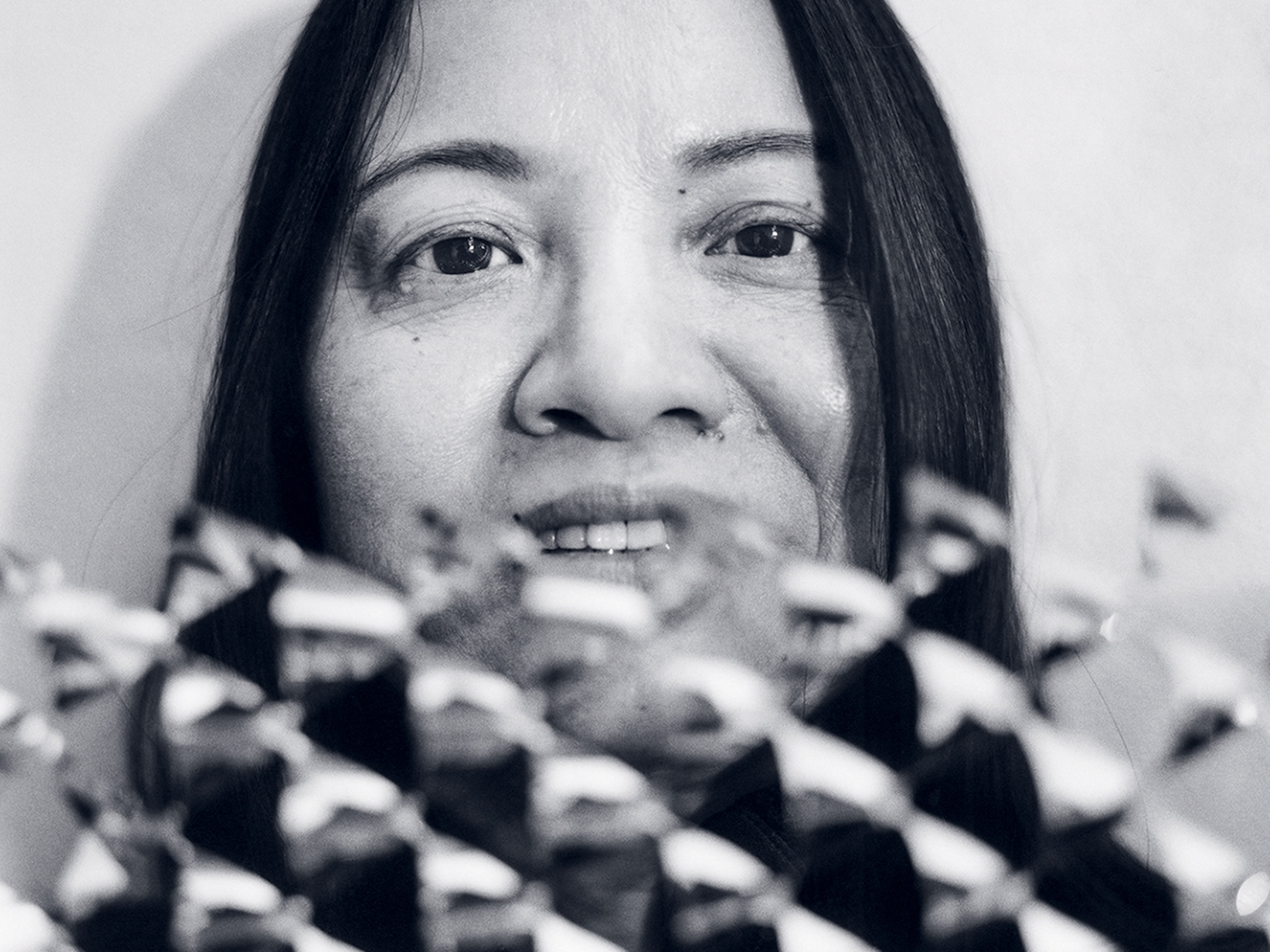

To make the pricey brew, captive Asian elephants are fed a mix of coffee cherries and fruit, and their stomachs break down the plant matter through fermentation, stripping it of its bitterness, according to company founder Blake Dinkin, a Canadian who launched the venture in 2012. He currently works with the owners of seven elephants in northern Thailand’s Surin Province to make his whole coffee line.

Dinkin advertises Black Ivory Coffee—the only major elephant poop coffee on the market—as having notes of “chocolate, cacao nibs, light peach, tamarind” and black tea, flavored in part by what else is in the herbivore’s stomach.

The coffee’s price has taken a leap over the years—from $60 for a couple servings in 2012 to $150. A full pound costs $1,500.

The pandemic boosted the company’s sales and global interest: Direct-to-consumer sales of elephant poop coffee exploded when people were at home and eager to try something new, Dinkin says. The product got a shout-out in a recent episode of Apple TV’s drama “The Morning Show.”

As highlighted in the episode, it’s now the world’s “rarest coffee,” with production only amounting to about 500 pounds in 2023.

More poo-to-brew options are garnering interest. There’s Brazil’s bird poop coffee, made from the washed and roasted coffee cherries gathered from the feces of the jacu, an endangered South American bird. Also, monkey parchment coffee—monkey-chewed (but not pooed) coffee beans. Then there’s the most well-known “naturally refined” coffee option: kopi luwak, which is sourced from the poop of cat-like creatures called civets native to Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Civet poop coffee has been around for decades—National Geographic magazine first reported on it in 1981—but the product continues to resonate and has even grown in popularity. One recent market analysis valued the kopi luwak coffee industry at $6.5 billion in 2021 and predicted that it would reach as much as $10 billion by 2030, with growth particularly in Indonesia and India, among other locales.

“I think a large part of it is the novelty factor, having an interesting story to tell your friends,” says Neil D’Cruze, global head of wildlife research at London-based World Animal Protection, an international animal welfare nonprofit.

Animal welfare concerns

Though each of the brews’ main selling point is the avant-garde sourcing and beans free of the bitterness of the standard cup of joe, the details of the supply chain and potential animal welfare concerns may differ with each product. All require further scrutiny, D’Cruze says by email.

Kopi luwak primarily comes from the Indonesian islands of Java, Sumatra, and Sulawesi, but it’s widely available in the U.S., Europe, and across Asia. The priciest kopi luwak offerings comes from wild civets that wander the forest and, as part of their natural diet, eat coffee cherries that are then excreted, collected, washed, and processed. But many of the kopi luwak offerings come from captive animals, with inherent animal welfare and zoonotic disease risks if the animals are kept in cramped, stressful conditions. Some researchers suspected a species of civet was an intermediary for the COVID-19 virus jumping to people.

(Related: The hunt for the next potential coronavirus animal host)

These solitary, short-legged mammals are often fed poor diets in captivity that may include only the coffee cherries, leaving them emaciated and ill, work by D’Cruze and others has found.

Those captive civets may only live two or three years, says Vincent Nijman, who directs wildlife trade research at Oxford Brookes University in the U.K. “If you give them only coffee berries that’s not a balanced diet. That will lead to health problems and, ultimately, death,” he says.

(Related: How coffee consumption influences human health)

Wild civets, by contrast, have an omnivorous diet that includes various plants and small animals like rodents, lizards, snakes and frogs, and insects. For producers trying to maximize civet coffee, however, it’s easier and cheaper to just buy a new civet rather than keep the animals healthy, Nijman says.

It’s hard to know much about the health and welfare for the other animals in the poop coffee industry since there hasn’t been much analysis, says D’Cruze.

“The existence and prevalence of caged production systems for jacu and monkey parchment coffee are currently unclear. However, based on the severe animal welfare concerns that were uncovered in relation to the civet-coffee industry, customers should take caution,” he says.

Black Ivory Coffee, the product made from Asian elephant poop, is free of the animal welfare concerns associated with civet-produced coffee, claims Dinkin. Elephants cannot be readily fed anything they don’t want to eat, he says, and he says he does his best to only work with families who treat their elephants well, and find elephants that are considered too old, physically injured or otherwise not appealing for the tourism industry.

“It is a mistake to lump all coffee processed via an animal as the same just as one would not lump all grapes the same to make wine,” Dinkin says. “Authenticity is another important factor. We video every feeding to ensure the elephant are happy and that the coffee cherries are actually consumed,” he says.

D’Cruze counters that though there is little publicly known information on the living conditions and management practices of elephants used in the coffee industry, the animals are still captive, penned animals.

For the civets, at least, caffeine exposure doesn’t seem to be a major concern. The beans seem to survive basically intact through their digestion process—arriving somewhat pitted on the other end.

“Caffeine would be present in the seeds but sequestered in the bean itself,” limiting caffeine absorption, says Robert Poppenga, the head of the toxicology section at the California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory at the University of California, Davis.

“This would be similar to ingestion of whole castor beans containing ricin—if not digested, the beans (and ricin) just pass through the GI tract,” he says, though he cautions certain other animal species may have elevated sensitives or further chew and digest the beans.

Luxury products

No one would accidentally consume any of these boutique coffee products at their local coffee shop. Kopi luwak retail prices range widely—from $45 per pound for coffee from farmed civets to $600 per pound for wild-collected beans, according to D’Cruze. When the product’s shipped internationally, prices spike to as much as $100 per cup.

Meanwhile, jacu coffee is sold at the luxury Harrod’s department store in London among other locations—though the product was currently out of stock at publication time and did not respond to National Geographic’s request for comment. Harrod’s online ad for it says the coffee relies on the pheasant-like bird selecting “only the very finest of coffee berries to ingest.” The monkey parchment coffee is primarily found at specialty roasters and Black Ivory Coffee is sold at luxury hotels in Thailand and elsewhere.

The kopi luwak industry is by-far the most well studied, says Nijman. In one recent analysis of civet coffee tourism plantations in Indonesia, his team concluded that sometimes it’s likely fakes—just standard coffee with a small percentage of kopi luwak— slipped into the booming industry or that the coffee is being produced by animals that are not on display.

“We make a back-of-an-envelope calculation on how much civet coffee we see in the shops and how much the civets can produce,” he says, and when the numbers don’t add up “this suggests to me that much of the civet coffee is not real,” he says.

Some civet coffee plantations have also increasingly branched out to include tourist interactions, raising new concerns about the animals’ welfare. An analysis of Trip Advisor reviews from 2011 to 2020 suggested that such civets sometimes appeared to be sedated to better enable tourist photos.

(Related: What climate change means for the future of coffee)

As for the taste of poop coffee? “As an avid coffee enthusiast, I’ve had the opportunity to experience genuine cage-free or free-ranging civet coffee,” D’Cruze says.

“While the taste was indeed slightly less bitter compared to ‘traditional’ coffees,” he says, “I found that the flavor profile didn’t justify the substantial price tag or the ethical concerns associated with the wider caged industry.”