California Sea Lions Keep Getting Shot by Fishermen

Despite legal protections for sea lions, fishermen resort to lethal force to keep them from stealing their catch.

Every morning keepers at Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium shake rattles and blow whistles to let Cruz—a 225-pound sea lion—know it’s time for breakfast. He’s blind, so his keepers rely on sound, touch, and scent to guide him around his enclosure.

Cruz’s story began in 2013, when rescuers found him stranded on a crowded beach in Santa Cruz, California. The rescue team says he appeared exhausted, underweight, and altogether helpless. But it was his eyes that worried them most—the left one was foggy, and the right eye was missing.

The wounded sea lion was rushed to the Marine Mammal Center, in Sausalito, where X-rays revealed several metal shards lodged in his skull. He’d sustained at least one shotgun blast to the head. He was nursed back to health, but because he was no longer able to fend for himself in the wild, the Shedd Aquarium took him in. Today, according to his keepers, Cruz is thriving. (Read about sea lion rescues.)

“He was one of the lucky ones” says Madelynn Hettiger, the aquarium’s manager of marine mammals. “If he hadn’t made it to shore, we might never have known about this animal.”

This year more than a dozen bullet-ridden marine mammals, including a pregnant bottlenose dolphin, have washed up on U.S beaches. According to NOAA Fisheries, the agency tasked with enforcing protections for marine mammals, as many as 700 California sea lions were found with gunshot and stab wounds between 1998 and 2017. Only a handful of the perpetrators have been charged, all of them fishermen.

Sea lions, as fisherman Brand Little knows from experience, are highly intelligent animals, adept at pilfering salmon, sardines, and squid dangling from a hook or caught in a net. We spoke with Little on May 3, the second day of the commercial salmon season, after he’d steered his boat into Santa Cruz harbor to unload his catch—37 king salmon, worth roughly $4,500. It had been a successful outing, Little said. “I only lost one fish.”

That fish hadn’t broken his line or wriggled off his hook—it was stolen by a California sea lion. Wherever fishermen go, Little says, sea lions are bound to follow. “You can’t run from them. We picked up and ran for six hours, and they’ll follow you. Six hours! Three of them on either side.”

When we asked another Santa Cruz-based fisherman how he keeps sea lions from making a meal of his catch, he said bluntly: “Shotgun.” The fisherman, who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity because he feared legal repercussions, says losing fish to sea lions threatens his livelihood.

“I’ll stay out there until my shoulder’s black and blue,” he said, alluding to the bruising from his shotgun’s kickback. “It’s my fishery. I have a right to go after my catch.”

For various reasons, including climate change and habitat loss, salmon stocks along the West Coast have been declining for several decades. As a result, fishermen say they can no longer lose fish to what they call “the sea lion tax.”

“It gets frustrating,” the fisherman continued. “Sometimes you’re going all day, going around for eight hours. And you’re $150 into fuel for the day, and finally you get a bite. You’re bringing it up, and then you watch a sea lion rip it off.”

Sport fishermen also complain about sea lions. “They steal our bait constantly,” said Evan Wagley, owner of Guardian Charters, a San Diego-based sport fishing charter company. The sardines and squid he uses as bait attract sea lions, which have figured out the best way to steal those morsels. “They know that if they swallow the bait whole, they’ll get a hook in their mouth,” Wagley said. “So they just bite the body.”

Fishermen have tried everything to ward off sea lions: paintball guns, firecracker “seal bombs,” which are low-yield explosives, even electric cattle prods. “I’ve tried a slingshot,” the Santa Cruz fisherman who asked not to be named said resignedly. “I’ve tried a few things—they don’t care.” In his experience, the only way to keep hungry sea lions at bay is a barrage of bullets. (Read about wacky sea lion deterrents.)

Scientists from NOAA have evaluated the effectiveness of a myriad of deterrence methods—ranging from rubber bullets and bottle rockets to recordings of predatory killer whales to scare off sea lions—and concluded that “there is no single non-lethal deterrence method known to be universally effective in discouraging Pacific harbor seals and sea lions from engaging in problem behaviors.”

PROTECTED ON PAPER

Until the late 1950s fishermen along the West Coast of North America had no compunction about shooting sea lions. Oregon even paid fishermen a bounty of up to $10 per dead sea lion. But by the 1960s sea lion numbers had plunged to the brink of population collapse, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature, which sets the conservation status of species, listed them as very rare.

That decline was in part the impetus in 1972 for passage of the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA), which made it illegal to hunt, injure, or harass marine mammals. Sea lions subsequently rebounded, their numbers nearly tripling from just under 90,000 in 1975 to nearly 260,000 in 2014.

"Sea lion populations are healthy—a sign of the success of the MMPA and other statutes aiding the recovery of ecosystems,” said Penny Ruvelas, who leads the Long Beach branch of the NOAA Fisheries Protected Resources Division.

Scientists estimate that sea lion habitat can support up to roughly 300,000 individuals along the West Coast before natural processes would start thinning the population.

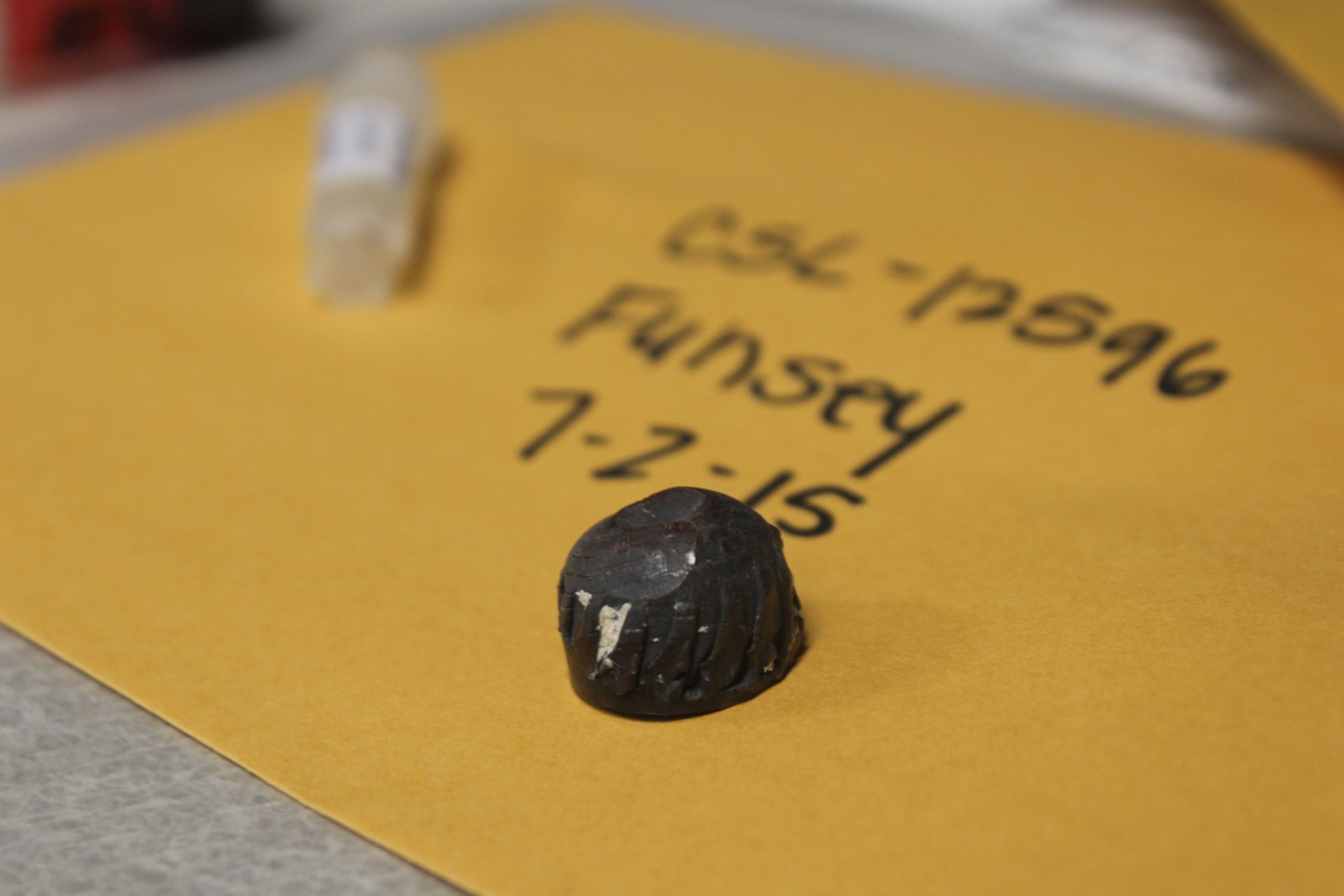

With sea lion numbers on the rise, the shootings, predictably, haven’t stopped. Filing cabinets in the Marine Mammal Center’s dimly lit basement contain bullets and pellets extracted from injured sea lions and other marine mammals over the years. Between 2003 and 2015 the center’s rehabilitation staff brought in 165 sea lions, two harbor seals, one northern fur seal, and one steller sea lion. Some arrived dead, others alive, but all had gunshot fragments in them. The bulk of the animals came from Monterey Bay during the summer, at the height of the salmon season.

Most shootings occur at sea, out of sight of any witnesses. The only evidence may be the bullets in a sea lion’s body, which may wash ashore days or weeks later—or may sink and never be seen at all.

Guns aren’t the only weapons used. In 2003 two men in Morro Bay, California, faced criminal charges for attempting to kill a five-month-old sea lion with a crossbow. And in 2007 a man in Newport Beach, California, used a steak knife to stab a six-foot female sea lion to death after the animal allegedly stole bait off his fishing pole.

“We know that the records of human-related mortality we collect are a minimum estimate of what the impacts could be,” said Lynne Barre, who leads the Seattle branch of the NOAA Fisheries Protected Resources Division.

Occasionally bullet-riddled sea lions are rescued, rehabilitated, and released back into the wild. But some, like Cruz and Silent Knight, a 700-pound male who sustained a shotgun blast to the face that blinded him, can’t survive on their own. Silent Knight is living out the rest of his years in the San Francisco Zoo.

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

The penalties for getting caught killing a sea lion can be up to a year in prison and or a fine of up to $25,000. But unless investigators have video evidence, an eyewitness account, or a confession, it’s next to impossible to track down violators of the MMPA, according to Barre. Since 2003 only five people in California have been convicted for the crime of injuring or killing a sea lion, and in every case an eyewitness was present.

Take the sentencing in March 2005 of John Gary Woodrum, the owner of 22nd Street Sportfishing in San Pedro. Two agents working for the NOAA Fisheries Office for Law Enforcement had posed as fishermen on his boat in an undercover sting operation, and they testified that they’d witnessed Woodrum firing his weapon at sea lions off Santa Catalina Island.

Woodrum admitted to using his .22-caliber rifle to shoot multiple sea lions. According to court documents, he was fined $5,000, sentenced to two months in federal prison, and ordered to do 250 hours of community service at the Marine Mammal Care Center, in San Pedro. And he was put on probation for one year.

Because it’s so difficult to catch people who kill sea lions, and even more so when the fishermen work at night, state agencies rely heavily on education and community outreach to cut down on violent reprisals against the animals.

In recent years NOAA scientists have been putting considerable effort into developing non-lethal ways of keeping sea lions and other pinnipeds away from docks, dams, and other man-made structures. Less attention has been paid to coming up with deterrents for use at sea.

NOAA posts information about non-lethal methods on its website, and marine mammal specialists like Barre speak to local fishing groups about how to make the best use of existing deterrents such as pyrotechnics, whistles, and airsoft guns.

“We’ve been trying to get more information out to fishing communities—particularly where we’re seeing higher incidence of animals that have been shot—to let folks know there are non-lethal options to try,” Barre said.

The agency’s education and outreach campaign has seen a number of small successes, such as an increase in the number of fishermen who inquire about non-lethal methods. But, Barre says, until scientists develop a truly effective sea lion deterrent, fishermen will likely continue to resort to illegal use of lethal force.