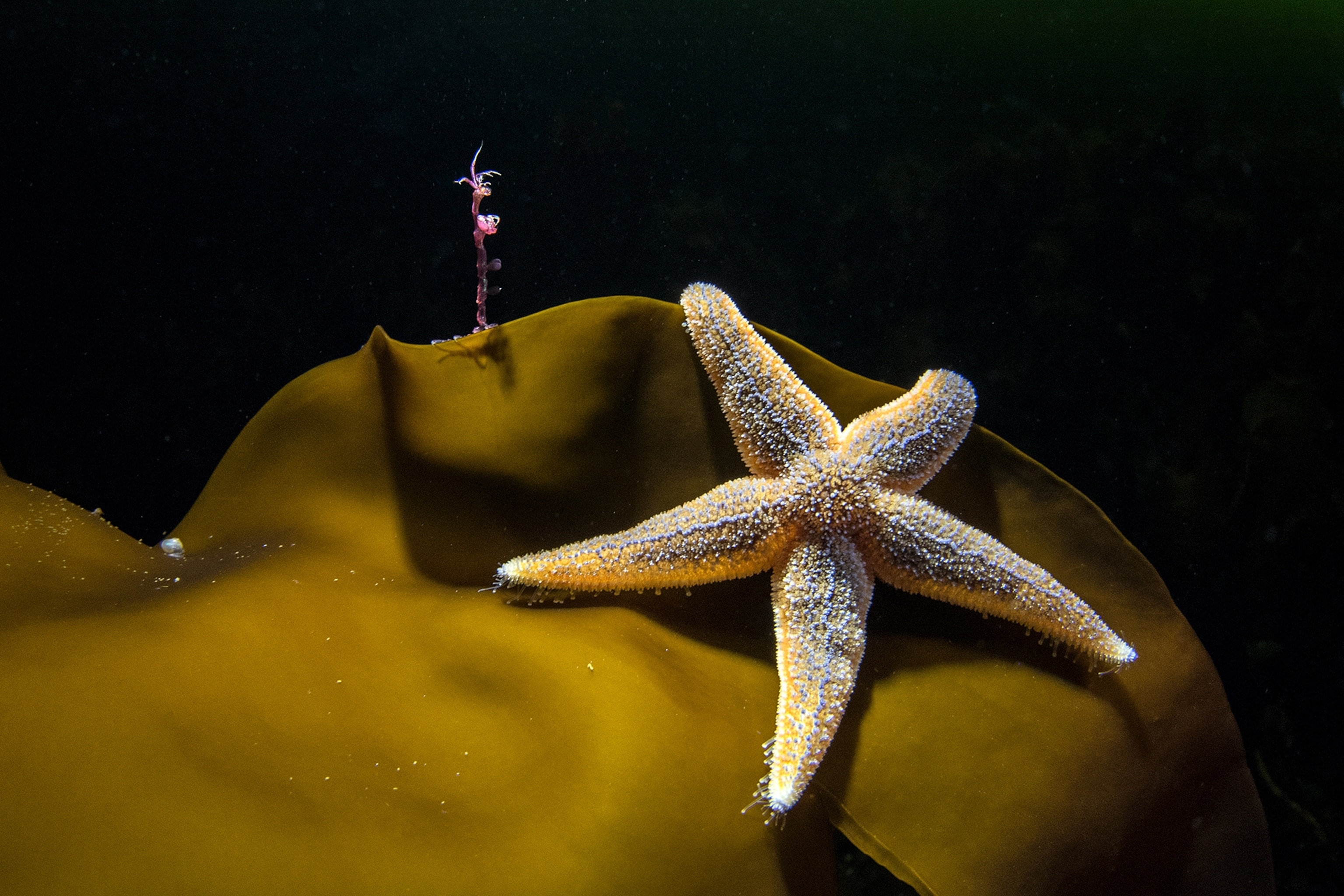

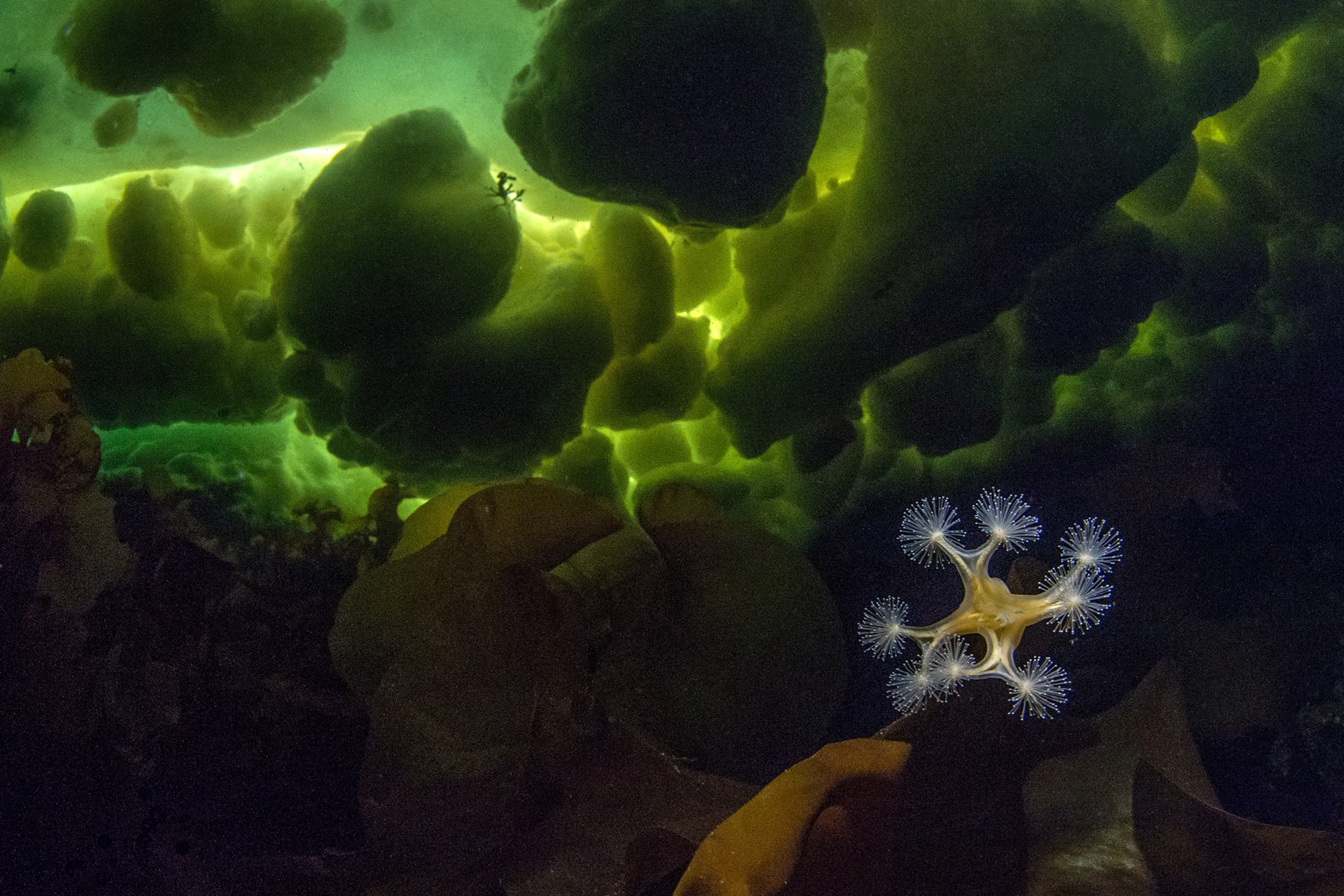

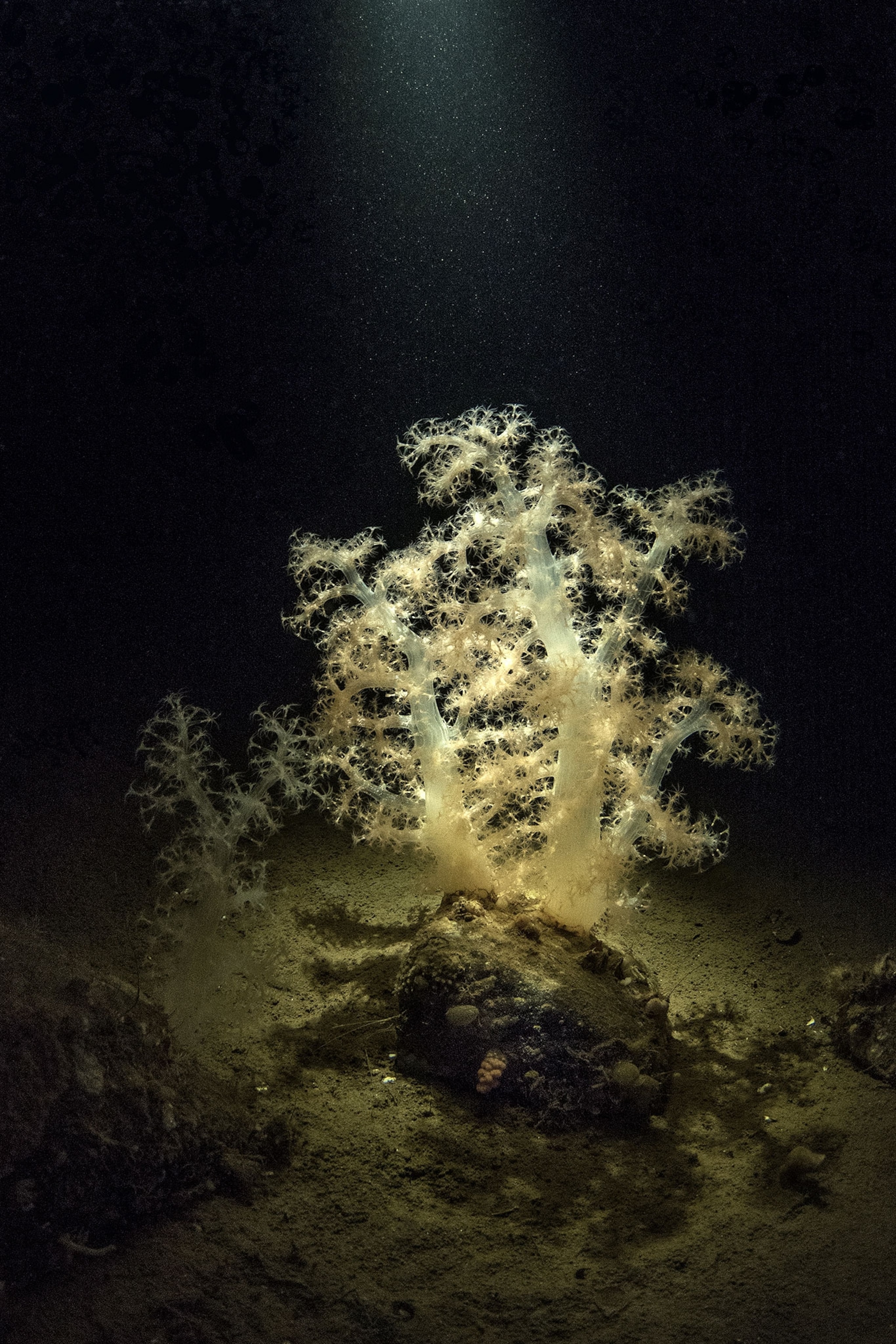

The waters of the White Sea are actually green, says photographer Viktor Lyagushkin, thanks to abundant phytoplankton in these icy waters straddling the Arctic Circle. Over 28 days in April, Lyagushkin spent around three hours a day under this ice in northwest Russia, photographing its incredible sea life including sea angels, caprellas, jellyfish, soft corals, and sea anemones.

Lyagushkin describes the dramatic scenes under the ice as otherworldly, and compares entering the water through a hole in the ice to Alice descending through a rabbit hole on the way to Wonderland.

He acknowledges that ice diving demands careful attention to safety, yet there are moments when he’s entirely consumed by the beauty before him. “It’s a great joy to shoot sea angels,” he says. Fascinated as one danced in front of his camera, he likens the experience to seeing a real angel. (See mesmerizing video of sea angels in a mating dance.)

On another dive, he witnessed a sublime underwater snowfall, which occurred when snow fell through the hole in the ice and was unable to melt in the salty, subfreezing water.

Not as uplifting, but equally beguiling, was discovering soft corals that were bent and laying on the ocean floor. He asked Mikhail Safonov, the founder and managing director of the Arctic Circle PADI Dive Centre and Lodge, what was going on. Safonov, who has a Ph.D. in biology, surmised that the animal had possibly been disturbed by a diver’s fin—unless, he joked, it was just “in a bad mood.”

The technical challenges of working in this extreme environment are abundant. Spending hours in subzero temperatures is physically exhausting, and also hard on the diving equipment. Between two people, 11 air-supply hoses exploded while working on this project alone. What’s more, Lyagushkin prefers to work with one or two assistants, and since they can’t speak underwater, they’ve developed special hand signals to communicate about where to position, and reposition, the lighting equipment.

To capture some of the White Sea’s littlest invertebrates, Lyagushkin uses both strobe and continuous lighting to show the animals in their aqueous environment, which is darkened by the ice cover above.

Although Lyagushkin has shot many underwater landscapes in the past, this project marks the first time he used a fisheye macro lens, enabling him to make detailed images of the tiny sea creatures, as well as their surroundings.

An image Lyagushkin titled “Cosmic Brain” features a Mnemiopsis ctenophore, also known as a sea walnut or comb jelly, floating close to the ice. Ctenophores don’t sting, but they are voracious carnivores, feasting on zooplankton including eggs and larval forms of assorted fishes and invertebrates, even other ctenophores.

It’s one of Lyagushkin’s favorite pictures. He says it looks like something that could illustrate Herbert Wells’ celebrated science fiction novels. Though small, just seven to 10 centimeters across, Lyagushkin imagines the ctenophore as a “giant and majestic alien brain living in a green world.”

With the work, Lyagushkin aims to show the “smallest creatures living with us in this enormous world.” His work highlights the way these animals live together in the White Sea, the only inland sea that freezes annually.

In general, he says, we know very little about the rich life in the seas. And because of global warming, the animals of the northern seas are perishing before we can learn more.

In the 15 years he’s been visiting the White Sea, Lyagushkin says the ice-diving season has become shorter and the ice thinner. During one recent September, he made a trip there to photograph jellyfish, but they had all died due to an abnormally hot summer.

With the dangers of climate change imminent, “it would be insulting to the species of the Arctic Ocean if we don’t find the time to study them and photograph them,” says Lyagushkin.