When you’ve got a tough exterior, there’s only one way to grow: Shed your skin.

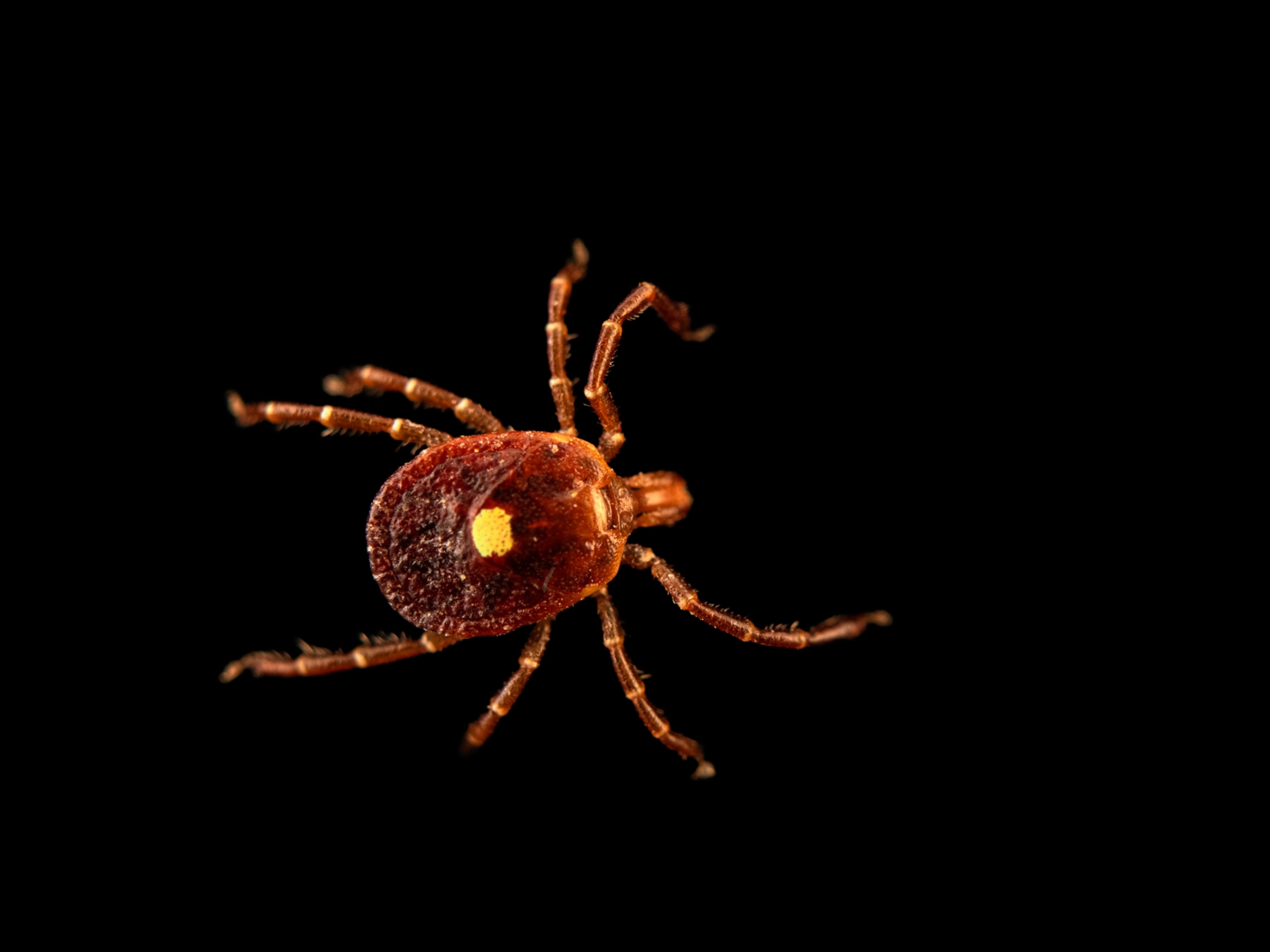

Arthropods, the most abundant group of animals on Earth, all possess a hard outer covering called an exoskeleton, which protects them from predators and supports their bodies. From a crab’s shell to a ladybug’s shiny back, exoskeletons come in a many shapes and sizes, but most are made of the same fibrous material: chitin.

When a young arthropod is ready to grow hormones trigger its skin to begin molting, a process known as ecdysis. The outer layer of the exoskeleton, the cuticle, and the layer beneath, the epidermis, begin to form a new, replacement cuticle. The animal then takes in a lot of air, which shifts fluid around its body to crack a suture, a weakened area on the exoskeleton.

Cockroaches, for instance, “split right down the middle of their backs” and “pop out maybe in 20 minutes or less,” says Andrine Shufran, an entomologist at Oklahoma State University. (Read why animals developed four types of skeletons.)

Aquatic crustaceans such as crabs take in water, which puts pressure on the seam running around their bodies. This pushes them of their old shells, like letters emerging from form-fitting envelopes.

Because crustaceans molt in one piece, “you can find perfect little empty skins of all sizes of crabs and horseshoe crabs, for example, scattered along a beach,” Christine Simon, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Connecticut, says via email.

Arachnids, such as tarantulas and scorpions, have less flexibility, so “they pop their heads off, and then pull everything out of that hole,” Shufran says.

Follow the tail

It’s only in old cartoons that turtles ever come out of their shells. In real life, a turtle’s shell is part of its skeleton and consists of “about 50 bones arranged like an intricate geometric design,” says Jeffrey E. Lovich, a research ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

On top of that bony shell are scutes (pronounced “scoots”), overlapping plates made of keratin. Turtles shed their scutes as they would skin, which may help the reptiles get rid of algae buildup on their shells or allow the shell to grow bigger, Lovich says.

Not all turtle species shed, however, and the timing can vary in those that do, says Whit Gibbons, an ecologist and professor emeritus at the University of Georgia who, with Lovich, co-authored Turtles of the World: A Guide to Every Family.

For example, painted turtles shed their scutes within a week, while slider turtles might shed their scutes over the course of a year, Gibbons says.

When a lizard is ready to molt, it often appears dull in color, with cloudy eyes, and begins to wiggle around. To make the first tear in its skin, the animal will rub itself on a rock or another textured surface. Eventually the lizard will work its way out, leaving behind a dead skin that often resembles a nylon stocking, Lovich says. (Read how metamorphosis works.)

Though the discarded skin is colorless, you can still tell a snake or lizard species from looking at the skin's patterns, Gibbons says.

“It’s like a black-and-white copy,” Gibbons says. The scarlet king snake, for example, has eye-catching red, yellow, and black bands that show up on its molted skin in various gray hues. Other factors, such as a shed skin’s size or scale type, can reveal what species of snake it came from.

Shed skin can even point to the location of its previous owner. Look at the tail, Gibbons says: “It’s pointing to where the snake went.”

Benefits beyond growth

Shedding skin also rids animals of ectoparasites—organisms that live on the skin of the host. For instance, when some Australian geckos get rid of their skin, they shed potentially harmful mites, too.

Some lizards and frogs eat the skin they shed, which is known as dermatophagy. Insects, such as Madagascar hissing cockroaches, also chow down on their former exoskeletons.

“It's good to hide any evidence that you’re around,” Shufran says, “but it also is a way to conserve all the energy that you've already put into your previous existence.”

After molting, it can take from less than a half an hour to several hours for an animal’s skin to harden, during which time it’s vulnerable to injury or predation. Female American lobsters move into a male’s burrow, molt, and then mate with the male, which then guards the vulnerable females for several days.

That kind of thing happens when you come out of your shell.