We finally know what caused Florida fish to spin in circles until they died

A new breakthrough points to toxins, yet the mystery of what sparked this bizarre phenomenon continues to puzzle experts.

After tireless months of data collection and testing, scientists have likely pinpointed the cause of the spinning and dying fish in Florida: a combination of toxic algae.

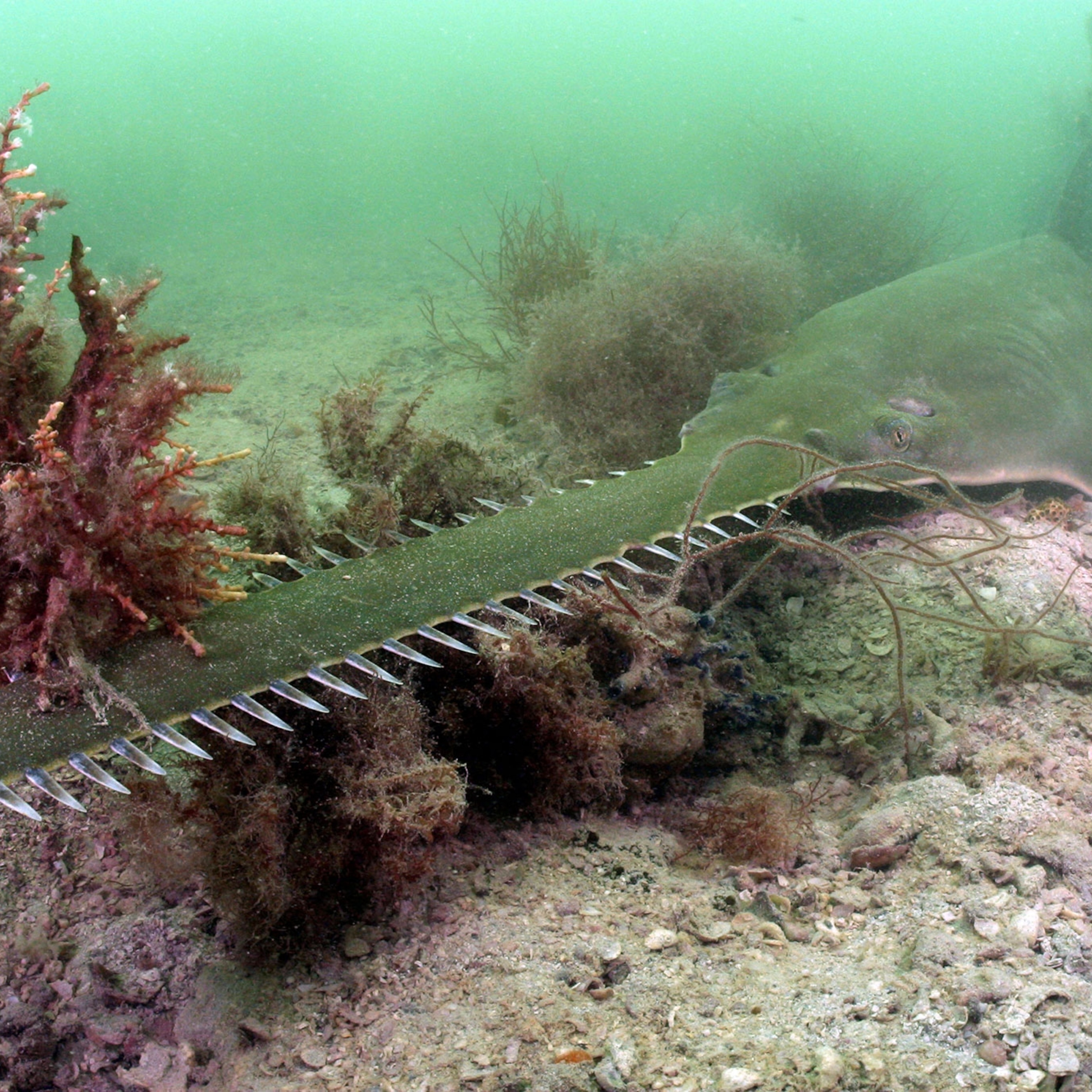

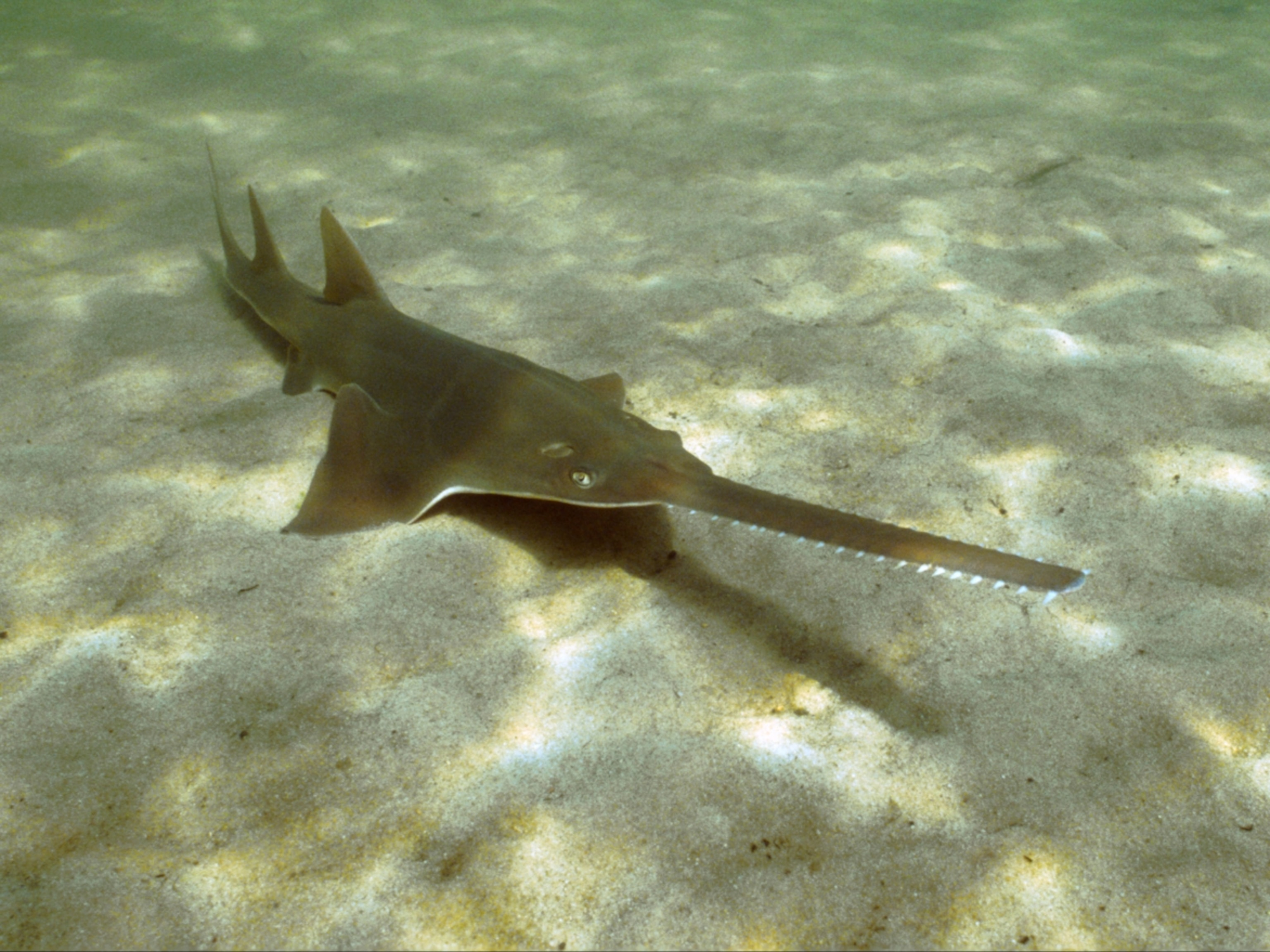

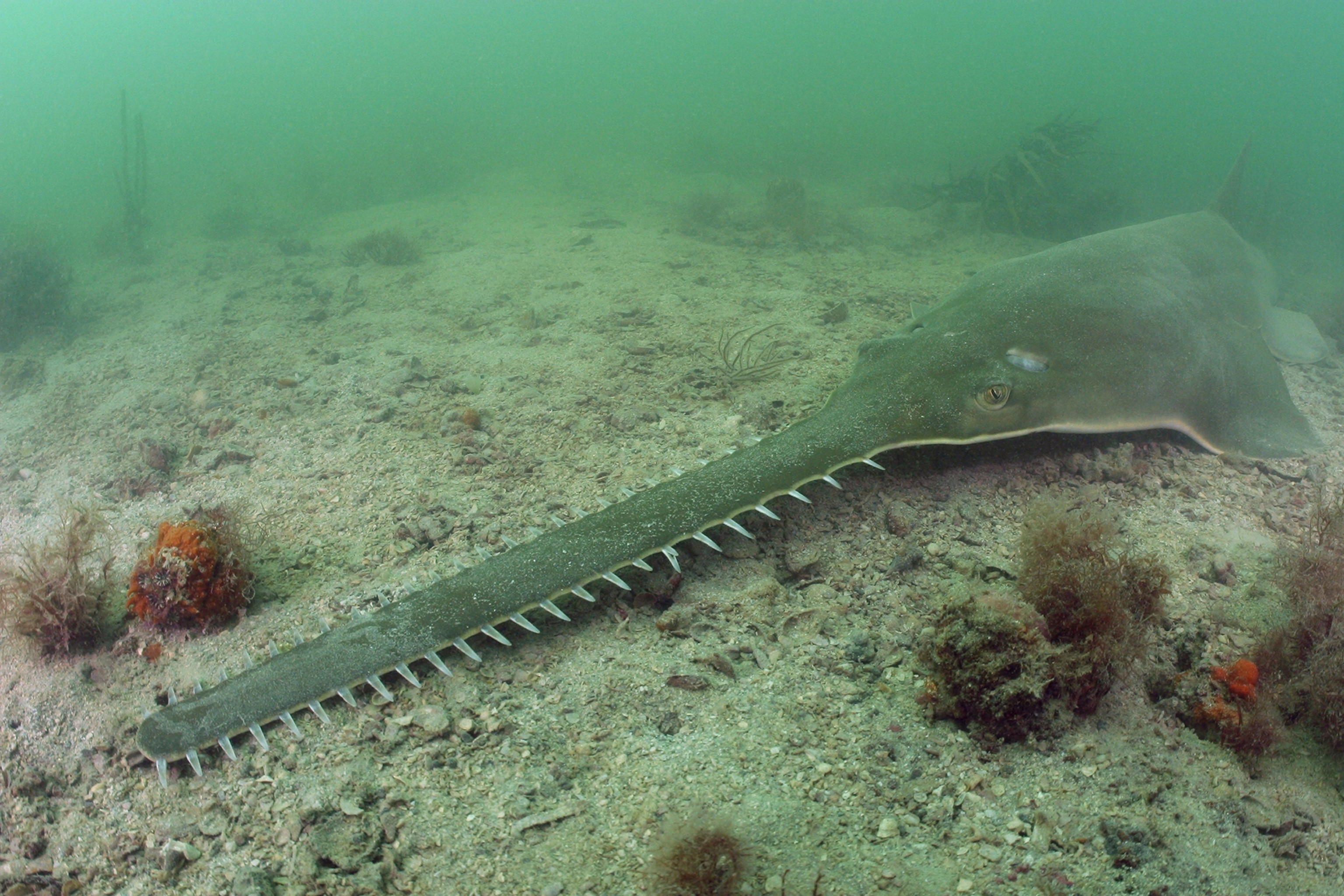

In November 2023, Florida Keys residents began observing fish and rays—including the critically endangered smalltooth sawfish—whirling in circles, usually until they died. Scientists later recorded the phenomenon in more than 80 species, including parrotfish, bull sharks, and goliath grouper.

This prompted a collaborative investigation between governmental agencies, nonprofits, universities, and more to figure out the culprit before it could set back decades of conservation efforts for the sawfish.

At least 54 of these unique rays, which sport tooth-studded saws, or rostrums, are confirmed dead—though many more likely also succumbed to the toxins, experts say. There are only around 650 breeding sawfish females in Florida.

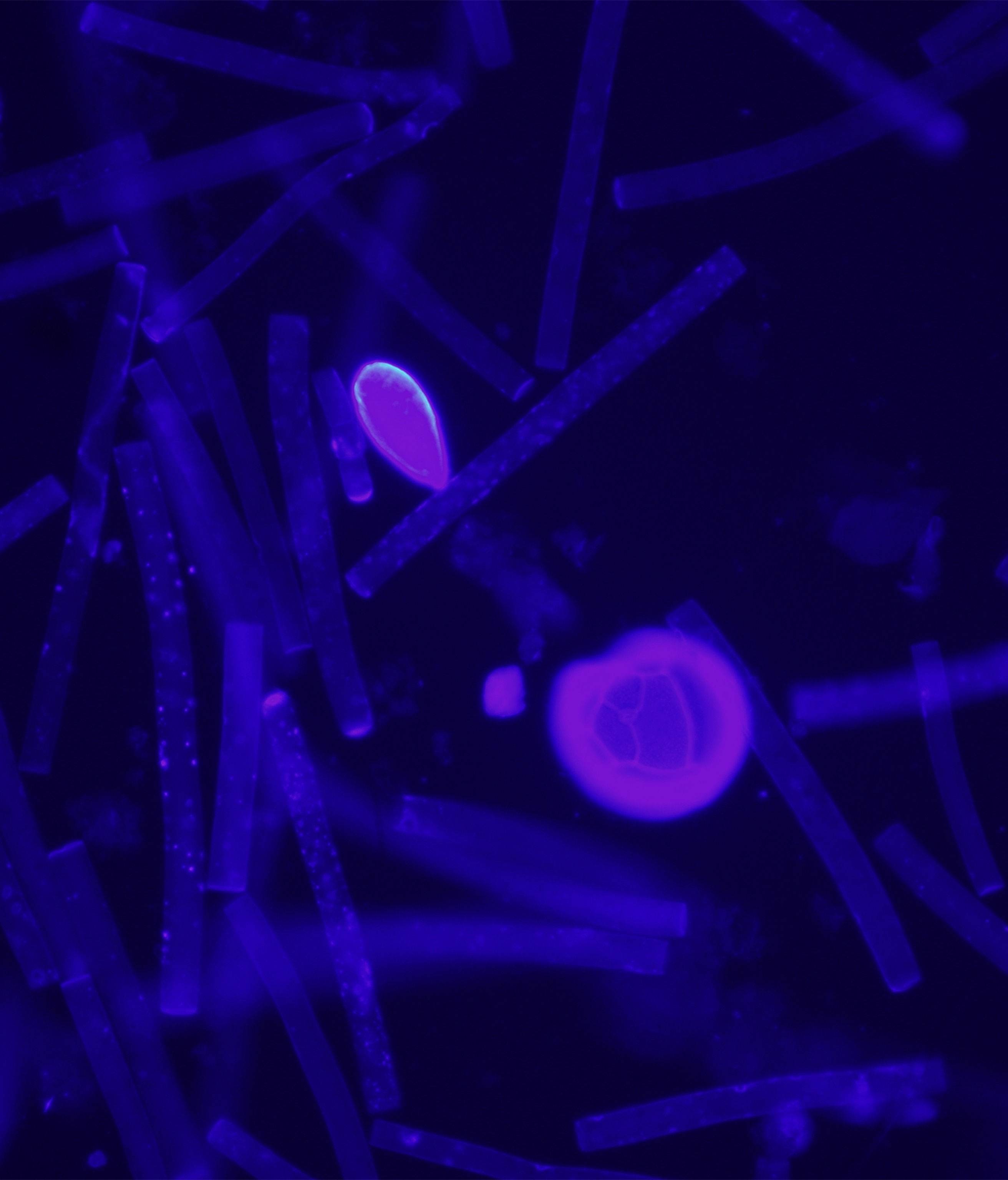

After testing hundreds of water and fish samples, the experts concluded the symptomatic fish died from combined exposure to multiple toxins, possibly originating from multiple species of dinoflagellates, a type of microscopic algae.

Under normal conditions, the dinoflagellates in question live on seagrass and larger algae on the seafloor, rather than free-floating in the water column. But some as-yet-unknown driver—possibly a heat wave, a storm, or a mix of events—caused the dinoflagellates to leave their hosts and move upward.

“It’s just really rare, we've really never seen that,” says Alison Robertson, a marine scientist who studies harmful algal blooms at the University of South Alabama's Stokes School of Marine and Environmental Sciences and the Dauphin Island Sea Lab. Whatever it was, “this is what we have to work out.”

While the Florida event is over—water samples from July revealed normal levels of algae in the water column—questions remain. Will it happen again, what caused it, and why were some species more impacted than others?

More toxic together

Early testing of the water ruled out a red tide event—a bloom of toxic dinoflagellates—and dissolved oxygen, salinity, pH, and temperature were all within normal range and not suspected to be a cause.(See photos of extreme algal blooms worldwide.)

The initial breakthrough came when work by Michael Parsons, a marine ecologist who studies algal blooms at Florida Gulf Coast University, revealed that levels of water samples showed higher than normal levels of a type of seafloor-dwelling dinoflagellate in the genus Gambierdiscus.

This algae produces a neurotoxin called ciguatoxin. People who eat seafood infected with this neurotoxin can experience ciguatera, a condition that causes vomiting, nausea, and neurological symptoms.

“Our biggest lead was this toxin-producing algae. So, we started there because of the human health implications,” Robertson says.

Robertson and her team didn’t find many toxins in the muscles of symptomatic fish, but their livers—the organ responsible for filtering out impurities—were chock-full of toxins, ranging from ciguatoxin to a variety of toxins produced by dinoflagellates other than Gambierdiscus.

“So, that’s the crux of it," she says—it's not just ciguatoxin alone. “Based on the evidence that we've been accumulating here in our lab, we believe that the behavioral effects that we have seen, particularly in sawfish, were associated with the combined exposure of a number of different [bottom-dwelling] algal toxins.”

“Some algae produce multiple toxins, so it is not a one-to-one relationship,” adds Parsons.

Sawfish hit hard

Once dislodged by that unknown event, the dinoflagellates not only spread throughout the water column, they concentrated toward the ocean bottom, says Robertson.

That’s exactly where 16-foot-long sawfish use their saw to hunt, catching other fish, crabs, and more.

When Robertson and colleagues examined some of the dead sawfish, they found toxin levels were greatest in both their livers and gills.

That means high concentrations of the toxin-laden water passed through sawfish gills, causing the neurological impacts. They also ingested toxin-laden prey.

Concerned about the fish's future, in spring 2024, for the first time in U.S history, scientists launched an emergency effort to rescue critically endangered sawfish impacted by the spinning phenomenon.

On April 5, they successfully rescued a distressed sawfish and began rehabilitation efforts at Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium in Sarasota, though the animal did not survive. Reports of ailing sawfish then declined. Yet in the event of a similar situation occurring again, a response team and protocol are now ready to act.

A big setback?

Smalltooth sawfish have been listed on the Endangered Species Act since 2003. their numbers in decline due to coastal development and bycatch. Only two populations remain in the Bahamas and the U.S., the latter being larger

Just last year, scientists celebrated 20 years of conservation efforts for the sawfish, such as banning the use of gillnets in state waters, says Dean Grubbs, a fish ecologist at Florida State University who studies the species.

The lasting impacts of this event on sawfish won’t be known for at least a couple years, Grubbs says. (Read about the search for the world's last remaining sawfish.)

“My gut is … this is a pretty big setback. Whether it's a setback that sets us all the way back to prior to them being listed as endangered in 2003, I don’t know.”

Silver lining

The investigation uncovered other intriguing findings, including a toxin new to the Florida Keys, according to Robertson. The toxin is associated with a European algae species, though the team found no trace of the algae in any of the samples. "We've got a lot of work ahead," she says.

The unprecedented event has been unfortunate, yet for Robertson, there is a silver lining.

“This is the first time that there has been such an intensive scientific investigation in the case, where many scientists have been brought together, sharing data to learn more about the Florida Keys ecosystem and ecosystem health.”