Searching for Clues to Mystery of Ancient Americans

Among the things they left behind are beautiful ruins, a gorgeously woven basket and a nearly impossible to get to granary on a cliff.

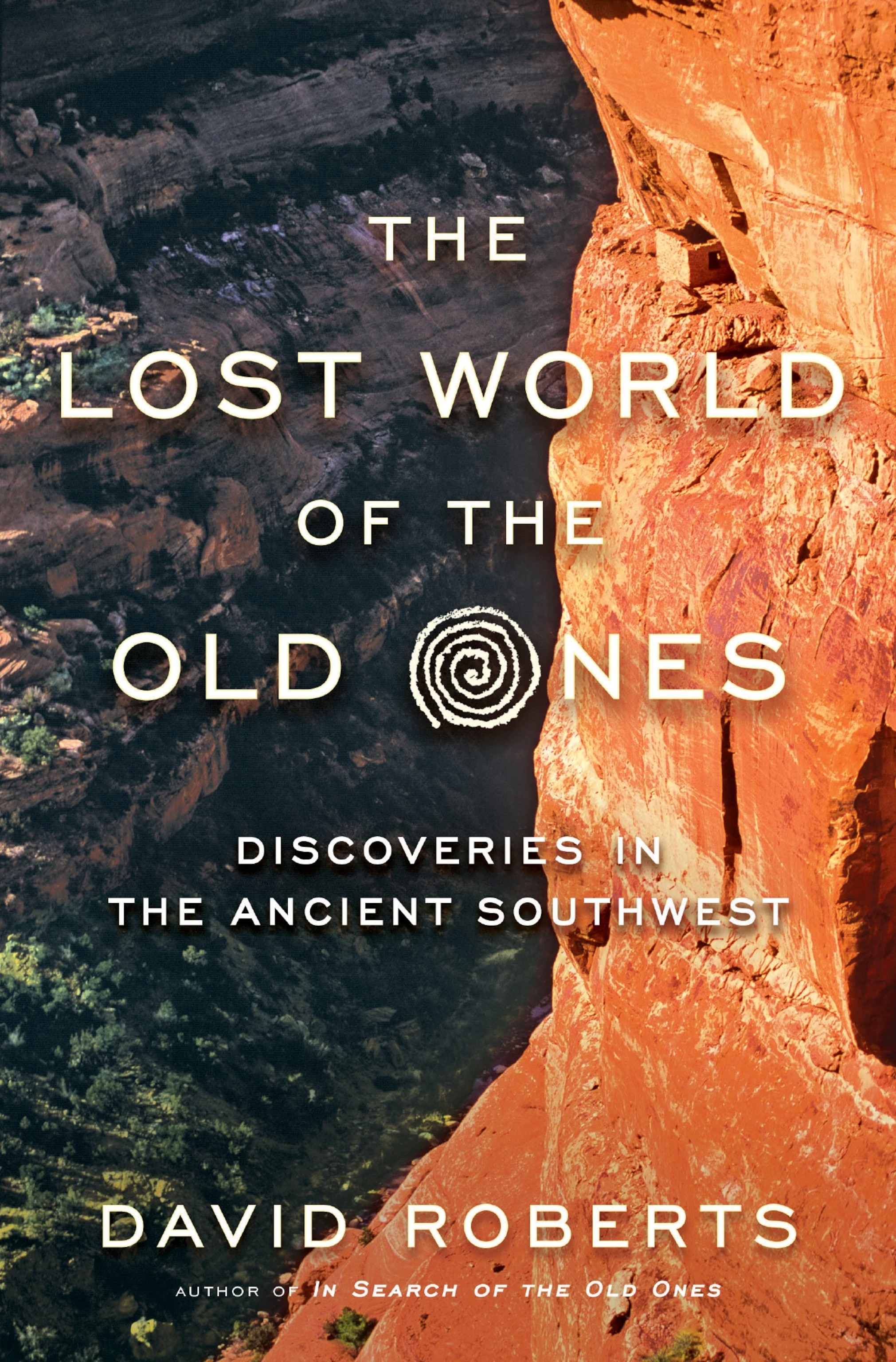

David Roberts is a well-known mountaineer who made the first ascents of some of Alaska’s most challenging peaks. For his new book, The Lost World Of The Old Ones: Discoveries in The Ancient Southwest, he set off with a backpack to explore some of the remotest corners of the American Southwest. Rappelling down cliffs to reach ancient granaries, or stumbling across artifacts that have not been touched for 1,000 years, he follows the trail of long vanished peoples.

Talking from his home in Boston, he explains why artifacts should be left where they are found and not locked up in museums; why the Dine leader, Hoskinini, should be remembered in the same way as Geronimo; and why the cave paintings of Desolation Canyon are so precious.

Obvious first question: Who are The Old Ones?

I use the [term] Old Ones because their descendants often refer to their ancestors that way. We’re talking about prehistoric peoples all over the Southwest, including ancestral Puebloans, who used to be referred to as the Anasazi, but also the Fremont, Hohokam and other peoples identified by archaeologists. Some are clearly the ancestors of today’s Puebloan Indians from Hopi to Taos. Others have vanished from the records.

The book starts with you clambering 90 feet up a cliff face in Range Creek, Utah to reach a granary. Tell us about Waldo Wilcox.

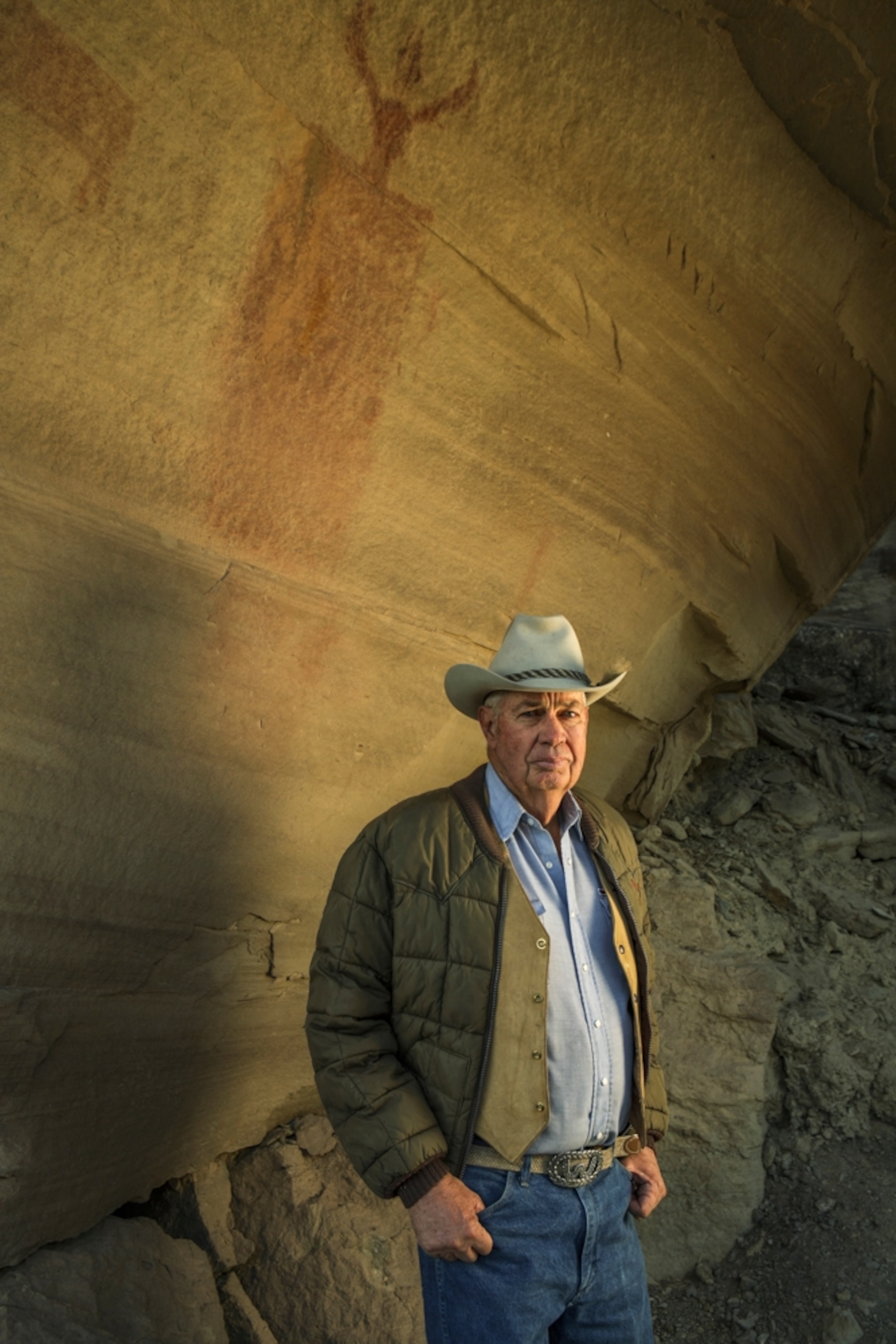

[Laughs] Waldo’s a character. He single-handedly kept a ten-mile stretch of Range Creek, one of the most remote parts of Utah, pristine and un-vandalized, for 50 years, while running a cattle outfit. A thousand years ago this was one of the richest places in the entire Southwest for the Fremont people. When Waldo, reluctantly in his old age, finally sold the valley to the state of Utah, it was opened up to archaeology. Everybody was astounded. Nowhere in the Southwest had been kept that pristine.

Waldo never stole or pocketed anything. He left all that “Indian stuff,” as he called it, in the ground. So, he’s one of the book’s heroes, because of his good, old fashioned cowboy drawl and his unique take on the landscape, which is so different from that of the professional archaeologists.

Who were the Fremont people? Why did they make these granaries so inaccessible?

[Laughs] You tell me! The Fremont are identified as separate from the ancestral Puebloans or Anasazi. They occupy the land directly north of ancestral Puebloan land—most of Utah north of the Colorado River, stretching into Idaho, the corner of Wyoming and the corner of Colorado. It’s a vast domain and it’s reasonable to think that these people were distinct from ancestral Puebloans. These wild, crazy granaries where they stored their corn, beans and squash required genius climbers to reach them, let alone to build granaries in them—as we found out when we hiked in to get to them!

You were a well-known mountain climber who did many first ascents in Alaska. How did your background in climbing affect your estimation of the ancient Puebloans?

Most archaeologists are not climbers, so they tend to minimize the difficulty of these sites. And they usually don’t get to them. The one that I open the book with is 90 feet up an overhanging cliff. There was no way we could climb up to it, so we ended up rappelling down from the top, with all kinds of fancy modern gear. The Fremont didn’t have that kind of gear and didn’t get to it that way. So we tried to figure out how they had done it and why they had done it. I think these are two questions archaeology hasn’t fully answered yet. You’re risking your life every time you go fill a basket of corn.

You call the disappearance of the ancient Puebloans “a mystery wrapped in a riddle.” Some people even think space aliens were involved.

[Laughs] Yeah, but they weren’t! And it’s not a disappearance. It’s abandonment. Modern day Puebloans are often infuriated to be told that their ancestors ‘vanished’ or ‘disappeared’. There were definitely migrations from the Colorado Plateau—to the south and east, where the Pueblos are today. But the Fremont, farther north, may indeed have vanished because nobody can link them to any living tribe today.

Modern day Puebloans are often infuriated to be told that their ancestors ‘vanished’ or ‘disappeared’.

You write that “language only compounds the mystery.” How so?

In the 21 Pueblos that exist today, there are four completely different language groups, comprising maybe nine or ten different languages. Some are cognates to each other, but some of them, like Zuni, are complete isolates like Basque and related to no other language in the world. If these Puebloans were descendants of the ancestral Puebloans, why don’t they all speak roughly the same language? Why do we have such an incredible variety of languages? Despite the apparent similarity in the way Puebloans look, there are huge cultural differences from the Taos to Hopi or Acoma.

Your earlier book, In Search of The Old Ones, attracted visitors to these remote sites and resulted in the looting of priceless artifacts. Yet you are against preventing access and removing the artifacts to museums. Why?

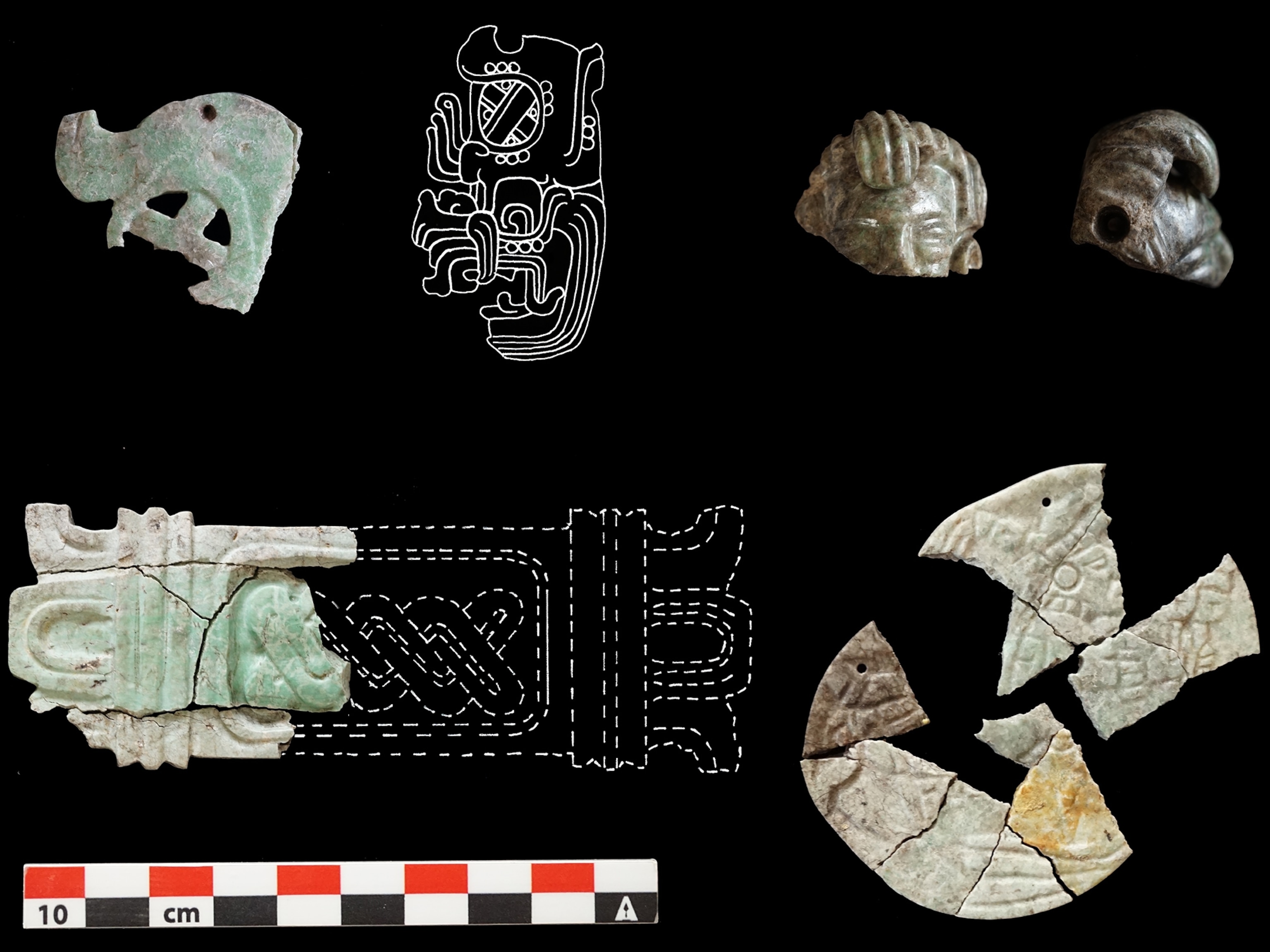

I’m a real advocate of what Fred Blackburn called, “the outdoor museum.” If you find something cool in that country, you should just leave it there. You shouldn’t call an archaeologist or a Bureau of Land Management (BLM) ranger and ask him to remove it. I’ve been criticized for this because people think these remarkable objects will, sooner or later, be looted or stolen. I’ve seen some of them vanish myself. But I feel that an object is just as lost in the drawers of a museum, where nobody ever looks at it, divorced from the place where it lay when we found it.

One of the many fascinating characters in the book is a guy called Steve Lekson. Tell us about the Chaco Meridian—and why it was such an important discovery.

Steve Lekson is my paragon of archaeologists. He’s also an iconoclast, who comes up with ideas that outrage his colleagues. The Chaco Meridian came to him in an Eureka! moment when he was looking at a map. He noticed that the three subsequent centers of the ancestral Puebloan or prehistoric culture—Chaco Canyon; Aztec, in northern New Mexico; and Paquime in Chihuahua, Mexico—lay on the same meridian, directly north and south of each other.

He thought that could not be a coincidence. So, he came up with the idea that the ancients moved on this dead straight north and south pilgrimage to establish first Chaco, then Aztec, then Paquime. This drove his colleagues crazy. They thought the Paquime had nothing to do with Chaco. It’s still a raging debate today. One of the happiest experiences of my life was to spend 11 days with Steve and a photographer, driving and hiking the length of the meridian, visiting all the sites.

A historical figure you profile—the Dine (Navajo) chieftain, Hoskinini—will probably be new to most readers. You say he should be celebrated “like Crazy Horse and Geronimo.” Why?

Hoskinini was a great Dine headman. They don’t have chiefs. But headman is like the leader of a band. In 1863, this crazy general, James Carleton, came up with a “final solution” to the Navajo problem: To force them to march 300 miles from their homeland to where there was a concentration camp in eastern New Mexico. A bunch of Navajos resisted, among them, Hoskinini. He fled with only 17 men, women and children, and was chased by Kit Carson. Hoskinini managed to escape by fording the San Juan River, and disappearing into a labyrinth of canyons where he hid out for four-and-a-half years. He not only survived, but prospered. His band became the richest Navajos in the whole Southwest. When the concentration camp collapsed in 1868 and the refugees returned, they were astounded by what Hoskinini had wrought. And I am astounded today.

Your book gives a lot of airtime to issues that are hotly debated regionally, like the disappearance of the Tewa people. Why should anyone outside of the Southwest care?

There are no ruins anywhere in the U.S. nearly as well preserved as the ones the Old Ones left behind.

[Laughs] There are no ruins anywhere in the U.S. or Canada nearly as well preserved or as beautiful as the ones the Old Ones left behind. There are great mysteries, too. My book is also a celebration of going out, hiking, backpacking and camping on my own or with a couple of cronies, looking for sites that very few people have ever seen. It has the thrill of exploration. It’s a real adventure.

You describe a wonderful-sounding rafting trip down Desolation Canyon, Utah. All of us are familiar with the cave paintings of Lascaux in France. How does the rock art you found compare?

The paleolithic paintings at Lascaux and Chauvet in France are unique. They’re also much older. They date as far back as 30,000 years, in the case of Chauvet. They’re also so well preserved because they’re in deep caves. It’s a completely different phenomenon in the Southwest because the rock art isn’t underground. It’s in alcoves: sculpted openings in sandstone. But the overhanging ceiling of the alcove keeps rain and snow and wind away. There are engraved petroglyphs and pictographs so beautifully preserved they look like they were painted last week.

Give us a picture of the motifs they were painting.

People have classified the different styles and periods, but some of the most haunting rock art is some of the oldest, Barrier Canyon style, which dates from at least 1,500 years ago to as far back as 4,000 or 5,000 years. Typically, you get these huge, red painted, armless humanoids with bug eyes and antennae coming out of their heads, and little spirit helpers, as they call them: tiny birds and animals running up their shoulders and flitting around their heads. They’re spooky and eerie and we have no idea what they signify. That’s where you this crazy space alien idea comes from. Some wackos actually believe that the Old Ones came from outer space, but it’s just not true.

The book ends with the story of an ancient basket. How does it symbolize what the ancient Puebloans mean to you?

About 20 years ago, Sharon, my wife, and I, were hiking in a canyon and she discovered a pristine, beautifully woven basket, which was at least 1,500 years old, tucked into a little cranny under these leaning rocks that looked like, if you touched them, they would collapse. It’s the single most amazing thing I’ve ever seen in the backcountry. I didn’t tell the rangers or anybody else where it was. So, for the last chapter of the book, Sharon and I and a couple of friends decided to hike back to into that canyon, and see if the basket was still there.

It was possible someone else had found it and stolen it. But, to our great joy, it was still there and looked just the same as when we first found it. I thought it was a nice way to round off the book and to make a last stab in favor of the outdoor museum – leaving artifacts in place for others to have the same thrill of discovery when they get there.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.