As darkness falls over Taipei City, an image of a woman named Lala illuminates the night sky. She’s one of Taiwan’s most famous live streamers, a niche group of celebrities who earn their fame through front-facing video cameras. Her face beams from a 100-foot-tall billboard overlooking Taipei.

Across Asia, countless other live streamers joke, eat, and sleep while being watched by thousands on smart phones and computer screens. The most successful among them can make fortunes enough to buy their own islands. But the industry’s hollow promise of intimacy can fuel a lonely existence for both stars and fans.

After a long day's work in a fabric factory, Junji Chen treasures time spent gazing into the eyes of his personal favorite, a live streamer known as Yutong. Having moved away from his village to work in Taipei, the 42-year-old has little social life. Most of his relationships are with Facebook friends, many of whom he has never met in person—and with live streamers.

Yutong cannot see Chen or hear his voice but, to him, their connection feels raw, real, maybe even reciprocated. To prolong the feeling, he needs only tap and swipe his index finger across the screen. In the comment’s section, he can flatter her with compliments or send her money in the form of virtual stickers.

One sticker can cost thousands of dollars, a steep price for a factory worker in a nation where the minimum wage is less than $5 an hour. But for lonely viewers like Junji, who spends a third of his salary on virtual stickers, the companionship is worth it.

Live streaming apps launched in Korea in 2006 as platforms for Internet celebrities to talk, eat, dance, or even sleep in front of a camera. They are now popular throughout Korea, Japan, China, and Taiwan. Platforms like 17 Media, founded in Taiwan in 2015, have more than 30 million global users and produce 10,000 hours of content daily. Exceeding 10 million downloads within 250 days of launching, 17 Media’s initial growth rate was faster than Instagram or Facebook.

24/7 entertainment

While hitchhiking in China in 2017, Chi Hui Lin thumbed open a live stream for the first time. Growing up in Taiwan, she watched the industry’s rise as advertisements popped up in big cities and platform names became part of casual conversations. But she never felt compelled to check out an app.

Even when she finally did so, she didn’t find the stream particularly entertaining. The industry is predominately—but not exclusively—female live streamers watched by male fans. Still, it sparked her curiosity.

Jerome Gence, a photographer and Lin’s travel companion, was equally interested. Gence became fascinated by the relationship between humans and technology during his work as a web analyst in France, but he had no prior exposure to the phenomenon. Lin and Gence decided to photograph live streamers and their fans throughout Asia.

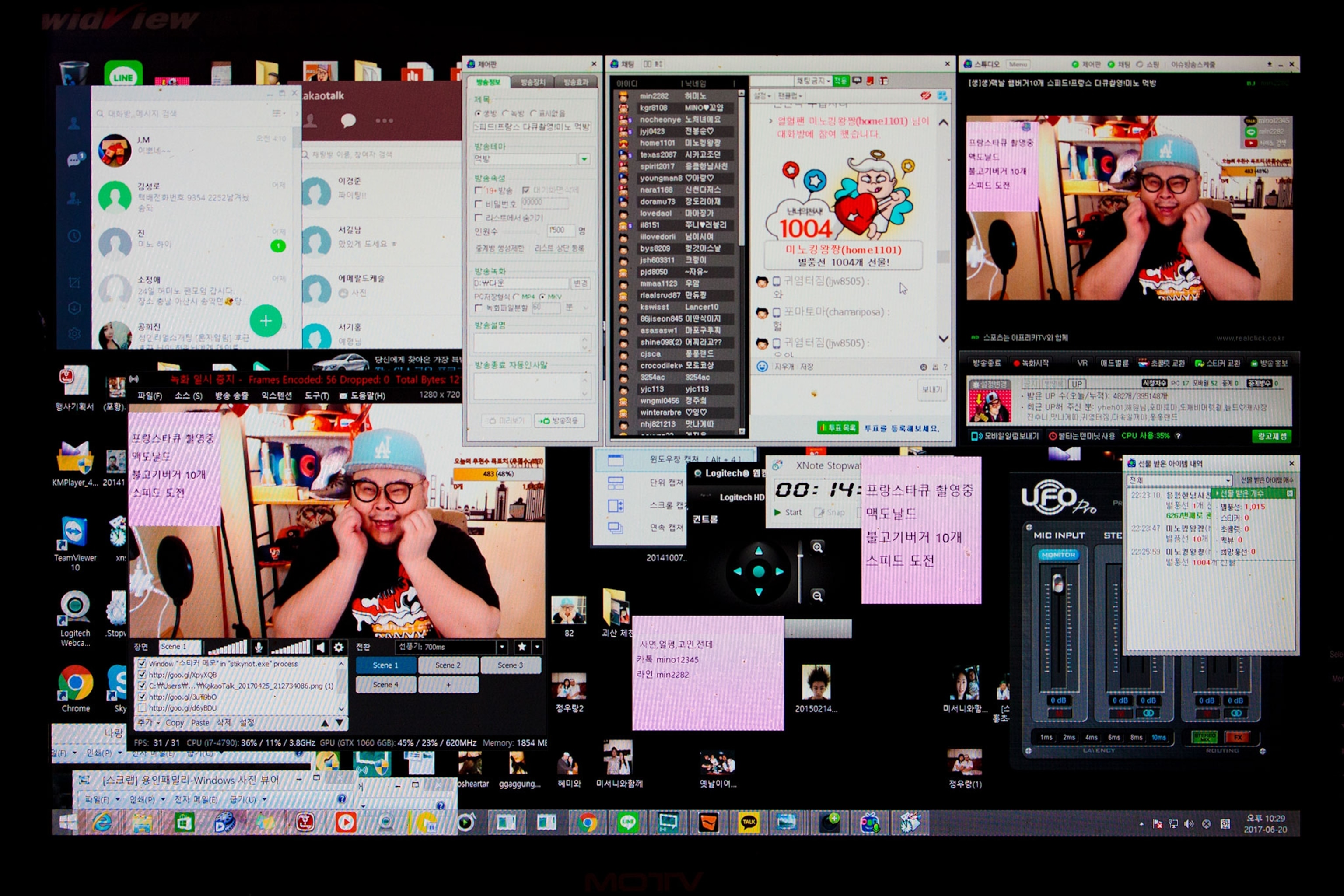

Over seven months Lin and Gence met the stars: a heavy set man eating massive quantities of food; a thin young woman altering the shape of her face with in-app filters; a dog who rides on a miniature car. They also discovered that the fluffy chairs and vibrant wallpapers visible behind most live streamers aren't the whole picture. “You have this colorful, awesome background,” Gence says. “But in front of them, you don't even have a window.”

Behind the screens

Within the live streaming industry, each country plays by a different set of rules.

Gence and Lin’s first stop was Redu Media, a Chinese live streaming agency with offices in Xi’an and Beijing. China monitors all live streamers closely and prohibits them from discussing politics over the stream. There, they met with live streamers who lived in close quarters with strict regulations. In Taiwan, Gence and Lin met at-home live streamers. Next, they visited hosts at Afreeca.tv, South Korea’s biggest live streaming company. In Taiwan, Japan, and Korea, live streamers may participate in political discussions and work from home, rather than at an agency.

The work can cause physical and mental harm. Peak hours are late at night, meaning irregular sleep schedules and fatigue. Some become isolated from friends and family or grow depressed. In Korea, live streamers who eat large quantities of food in front of the camera—known as Mukbang—are prone to obesity. Some purge after binging sessions, leading to health problems and even heart failure.

When Lala, a famous Taiwanese live streamer, goes to work, she leaves her five-year-old daughter, Mong Mong, at home in their flat. Lala’s mother told Gence and Lin that she feared her daughter had no authentic relationships outside of the industry—despite having almost 75,000 followers on LiveAf, an app produced by 17 Media.

Because a live streamer’s success depends on their digital popularity, they may continue unhealthy behaviors to please their fans. Once intimacy is lost, so is their source of income.

“Live streamers are insecure about this job because they are not sure how long their fans are going to like them,” Lin says. “The fans just need to swipe their fingers so they can switch to the next live streamer's session.”

Financially, few can live off the industry alone. According to 2016 data from WeChat, a Chinese social media app, more than 90 percent of live streamers worked another job, and only 17 percent stayed in the industry for more than two years.

Regardless, companies like 17 Media make their money. “The winner eventually is a platform,” Lin adds.

Easy targets

Kongto, a 32-year-old fan, lives at home with his parents in Miaoli, Taiwan. Having never kissed a girl, Kongto feels more capable of expressing love to a live streamer on the Internet than to a woman in real life. He watches his favorite live streamer, Yutong, in private, fearing his parents’ reaction if they learned of his habit.

Kongto is one of many bachelors who watch live streams to combat loneliness. This is especially prevalent in Asian countries where many young men must leave their family villages for work in city factories. Without a familiar face for miles around, they turn to live streams to make their new environment less isolating.

This generation is “more able to connect with each other in the streaming platform,” says Nan Zhang, a partner at the marketing firm Metis International who has been researching the live streaming industry in China since 2016. “With their parents or with their siblings or with their colleagues, they may not be able to say something or be authentic.”

China’s rapid shift from a collectivist to an individualist society plays a large role in young people’s decisions to watch live streams, adds Zhang. Additionally, China's one-child policy, first adopted in 1980, gave preference to boys. Today, millions of twenty-something men cope with their lack of female companions by tuning in to live streams.

She loves me, not

Live streaming fans can manifest “parasocial relationships,” one-sided friendships that appear reciprocated, with their favorite live streamers. For a person who lacks social skills, parasocial relationships can create the illusion of companionship when, in reality, the other person offers them little or nothing in return.

Kostadin Kushlev, an assistant professor of psychology at Georgetown University, has researched the impact of screen time and well being. He found that interactions over mobile phones or other technological devices cannot yield the same benefits as real-world relationships.

“These devices can connect us, theoretically,” Kushlev says. “But when we begin to replace those face-to-face interactions with digital interactions, we end up with this self-perpetuating cycle where we have the need to connect but we can’t.”

Fans believe that they are truly cared for, Gence says, but “in the end, [the live streamer] just takes the money and the fan ends up even more lonely than before.” Still, he adds, some fans still say the videos help cultivate friendship, or even love. “Some fans say to us, 'I follow the live streamer because they are the only one who knows my name.’”

Since wrapping up their project, the photographers found out that Junji Chen, the Taiwanese live stream fan, stopped watching his beloved Yutong. He recognized that the live streamers will never love him back, he told Lin, and wants to focus on treating himself better.