'Beer diplomacy' practiced in ancient empire’s dying days, artifacts reveal

A study of drinking vessels smashed after a party almost 1,000 years ago show how Peru's Wari kingdom brought high-level festivities to the edges of their crumbling empire.

Around 1050 A.D., the elites living at Cerro Baúl held a party to end all parties in their brewery.

Cerro Baúl was a colonial outpost at the southernmost edge of the Wari empire, in what is now Peru. Its location—on top of a steep-sided plateau with no natural water source—was totally impractical, particularly as it was also a destination for lavish banquets and beer brewing.

For four centuries, the Wari leaders of Cerro Baúl would host gatherings with their rivals from the neighboring state of Tiwanaku, as well as the heads of local communities who lived in the shadow of these two major empires. They would feast on guinea pigs, llama, and fish while enjoying the view over the Moquegua Valley and drink pint after pint of a beer-like beverage known as chicha, fermented from corn and pepper berries.

But at the end of this particular event more than 950 years ago, as the Wari empire was collapsing, the revelers concluded their festivities by trashing the brewery at Cerro Baúl.

It appears that the Wari had planned to evacuate their colonial outpost, and they had already destroyed its temples and palace. The brewery was the last to go. They set fire to the building and watched it burn. Wari nobles polished off their chicha and threw their prized drinking cups into the flames. When the brewery was reduced to ashes, some took off their necklaces and laid them on the embers as final offerings. Its ruins were covered with sand so that no one could ever use the building again, making the brewery a rare time capsule for archaeologists who have excavated the chicha-making center over the last two decades.

Researchers recently analyzed the ceramic vessels from that final feast at Cerro Baúl, and according to their findings published today in the journal Sustainability, the Wari likely kept their massive parties going at the borderland outpost colony late into the empire's collapse by relying on local sources for their brews and their drinking vessels.

Wari beer diplomacy

Cerro Baúl was a politically important site for the Wari, a people who ruled a wide stretch of the Peruvian coast and Andes from about 600 to 1050 A.D., and built extensive networks of roads and irrigation canals long before the Inca came to power. The diplomatic center was a two- to three-week journey southeast by foot to the Wari capital, Huari, and some of Cerro Baúl’s temples were dedicated to Tiwanaku gods in an attempt to woo their rivals.

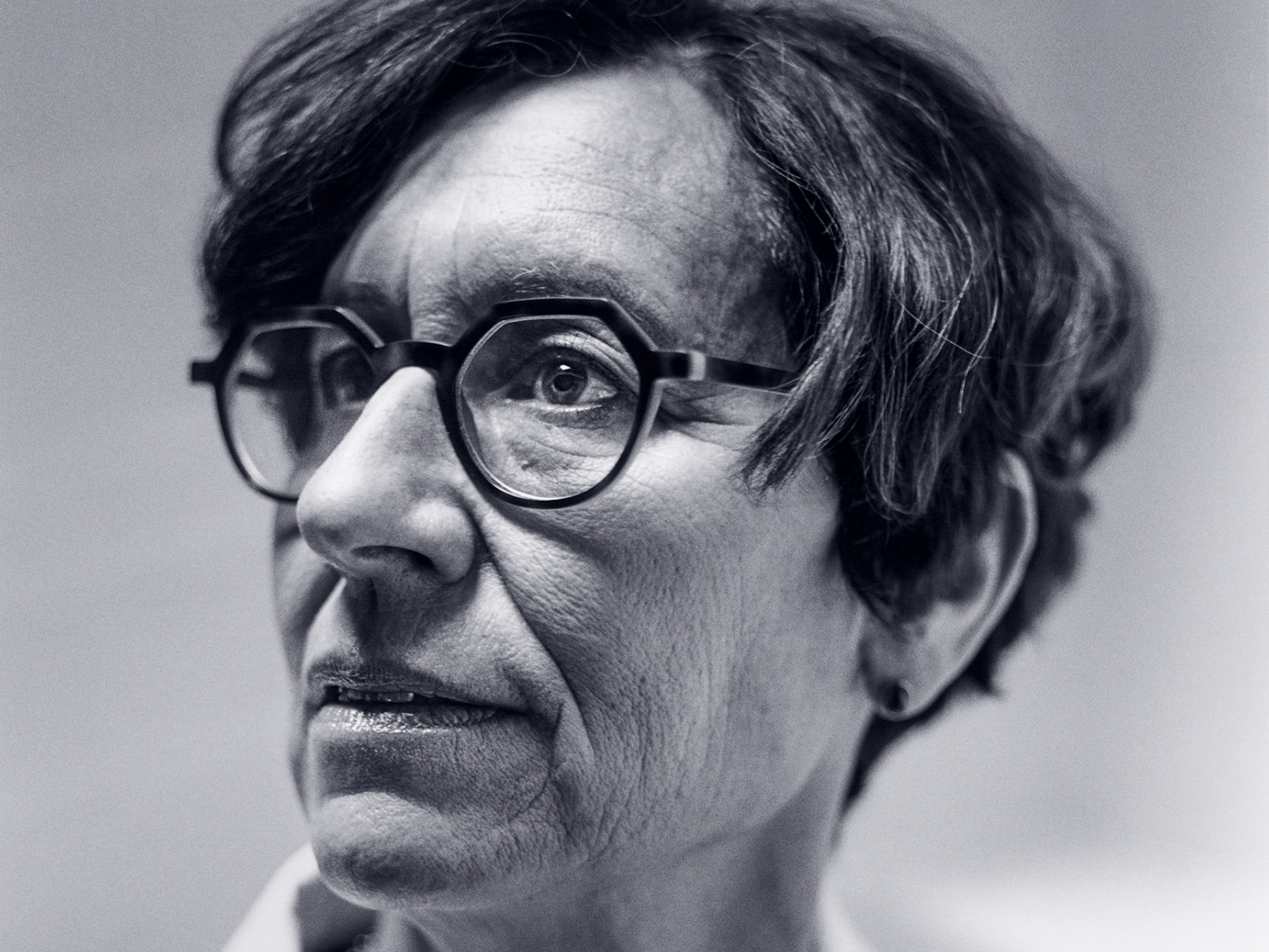

"We know that the Wari were trying to incorporate the diverse groups coming [to Cerro Baúl], and one of the ways they probably did that was through big festivals that revolved around the local beer," says the study's lead author Ryan Williams, head of anthropology at the Field Museum in Chicago.

Williams and his colleagues have estimated the brewery at Cerro Baúl was able to produce 400 to more than 500 gallons of chicha at a time, a large quantity for a pre-industrial brewery, especially because chicha tends to go bad after about five days. That means upwards of a few hundred leaders may have been invited to parties on the mountaintop.

For the Sustainability study, the researchers wanted to understand how the supplies for these banquets were produced. The ceramic brewing and drinking vessels—which were made to look like Wari gods—resembled ones found at their distant capital of Huari, but a chemical analysis of the smashed ceramics revealed that the drinking vessels at Cerro Baúl were made on site and sourced from local clay.

"I expected that those fineware drinking vessels would have been imported, but they are actually reproducing an entire Wari lifestyle in these provincial areas," Williams says. "That's really interesting because it does speak to this lack of dependence on the resources of a centralized state, which makes these local provincial areas much more resilient long term."

Recreating ancient brews

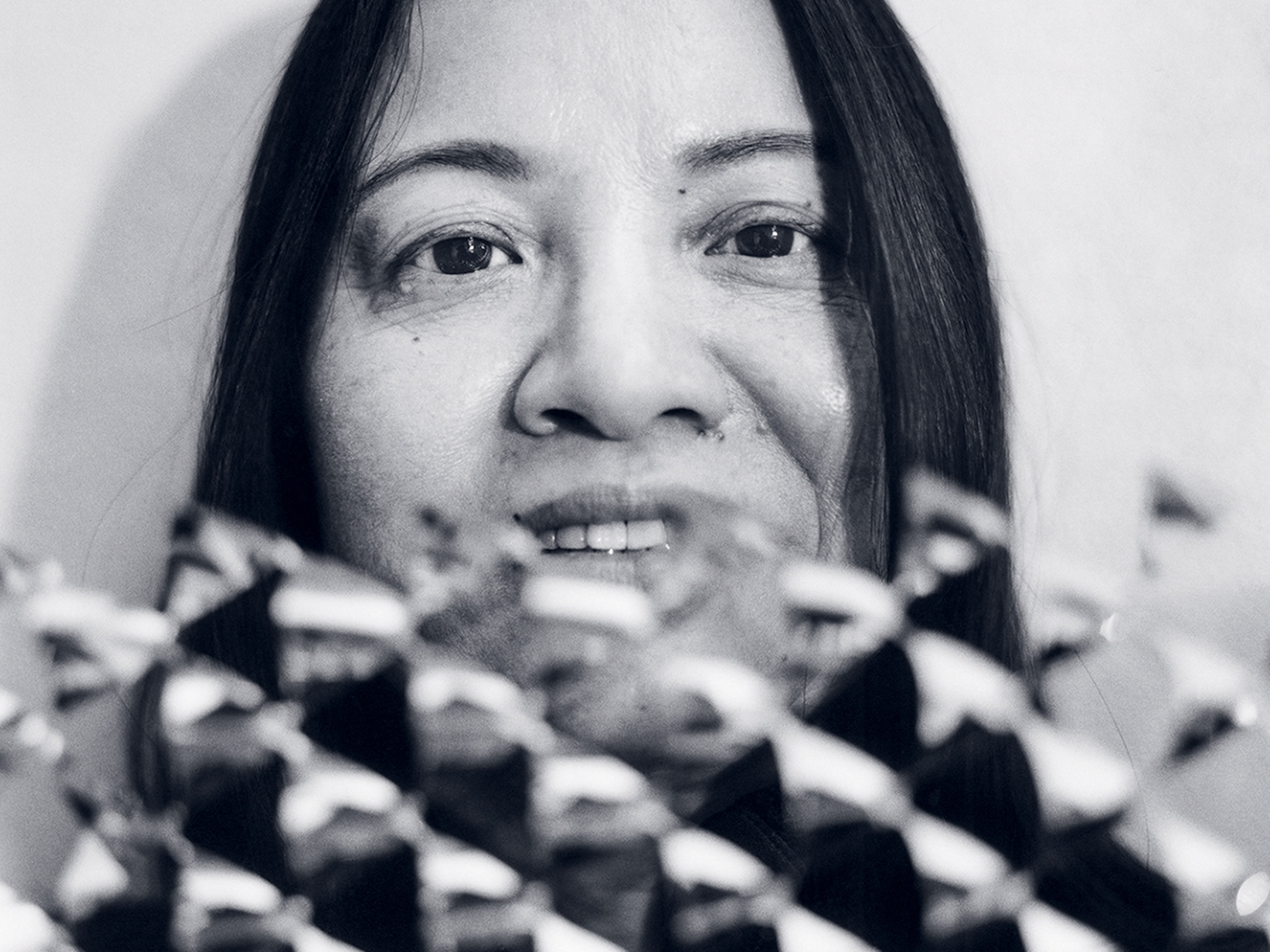

The ancient ceramics also contained chemical residues of chicha. To figure out what ingredients the Wari used in the brew, the scientists made chicha with the assistance of a woman from the nearby Andean foothills who knew how to brew the beverage, which is still common in the region today.

"It's very, very hard to pinpoint these chemical signatures without having experiments," says study co-author Donna Nash, an archaeology professor at the University of North Carolina Greensboro. Recreating a batch of chicha took a month from start to finish, and to make the process as authentic as possible, the team used ceramic pots to boil and ferment the ingredients, as well as llama dung to fuel their fires.

The experiments confirmed for the first time that the chicha at Cerro Baúl was made from corn and molle, the locally abundant Peruvian pepper berry. The pink pepper berries gave the chicha a delicate but potent taste, and it was difficult to get the brewing process right so that the drink didn't taste like peppercorns, Williams and Nash say. What's more, these berries are very drought-resistant, so the Wari would have been able to keep the beer supply flowing even during times when corn, a water-intensive crop, was unavailable.

Patrick McGovern, a scientist at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology who studies ancient alcoholic beverages, said the new study exemplifies "the best in modern biomolecular archaeology by applying sensitive scientific techniques to pottery and archaeobotanical remains."

"It demonstrates once again how ancient fermented beverages were central to human communities around the world," McGovern, who wasn't involved in the research, told National Geographic in an email.

Nash says there has been speculation that certain batches of chicha might have included hallucinogens; some Wari pottery features drawings of psychedelic plants like the San Pedro de Atacama cactus and the vilca tree. In future experiments, she'd like to find out if those substances were also present on the pottery from the brewery. Williams also says they're also hoping ancient DNA analysis will also reveal what strain of yeast the Wari were using in their brewing process.

Scholars don't know exactly why Cerro Baúl was abandoned, and they're still debating how the Wari empire fell apart. Did a severe drought lead to poverty and violence, as some bioarchaeological evidence suggests? Did political infighting breakup the empire? Regardless, Williams thinks Cerro Baúl could offer some lessons about the importance of building local resilience inside massive political powers—lessons that could be relevant for those living in the United States or the European Union, for example.

"One of the things we still have to work out is the Wari collapse across space and time," Williams says. "Some people argue that it happened around 950 A.D. Our last gasp seems to be around 1050. There may be a 100-year period where we see some places being able to maintain traditions even as other areas are suffering huge declines because of their resilience and local sourcing."

New World beer-making traditions have been somewhat overlooked, according to Williams, despite new interest in ancient brewing methods amid the craft-beer revolution. However, the Field Museum and the Chicago-based craft brewery Off Colour Brewing have created a "Wari Ale" based on Nash's work. The pepper berry-infused pink ale will be re-released in the Chicago area in June.