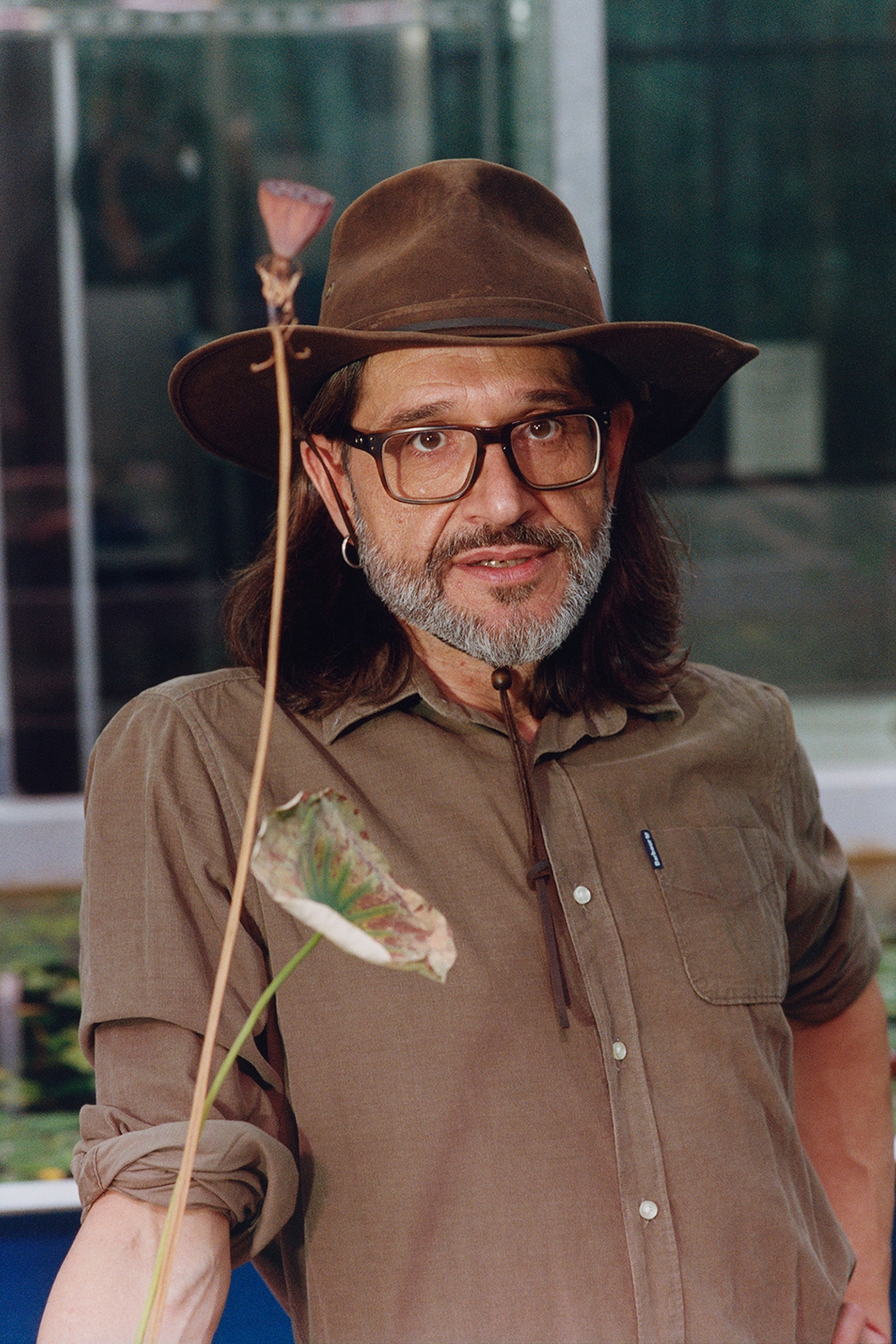

How ‘plant messiah’ Carlos Magdalena rescues endangered species from near extinction

The horticulturist travels the world in search of troubled species to propagate. His motivation? “Plants are the alchemists of our universe.”

The man they call the plant messiah, Carlos Magdalena, first heard about it in the news: the case of the café marron, or Ramosmania rodriguesi, a shrub from the Mauritian island of Rodrigues that was thought to be extinct for much of the 20th century. Until 1980, that is, when a schoolboy discovered a lone survivor on the side of the road. The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, in London, acquired a cutting, but the horticulturists there couldn’t get it to produce seeds. The café marron and its star-shaped flowers appeared doomed—until Magdalena arrived at Kew in 2003.

He was then a 30-year-old intern by way of Spain, but he started experimenting—amputating the stigma and placing pollen in the wound, growing the tree in warmer conditions. “And then,” he says, “all of a sudden, boom, I managed to do this”: propagating the café marron and reintroducing it to Rodrigues. “It was a lesson in conservation,” he adds. “If a plant cannot be saved, what is the point of keeping it alive? And the point is that maybe we cannot save it now, but we may be able to save it in 20 years.”

Magdalena, now a research horticulturist at Kew, has made reviving endangered species his life’s work. About 45 percent of flowering plant species are potentially threatened with extinction, according to Kew, but endangered mammals—whales, for instance—tend to dominate the headlines. “Maybe we are focusing on the top of the pyramid, when what we have to focus on is the base,” Magdalena says. “Plants are the alchemists of our universe.”

He’s journeyed to the cliffs of Mauritius, the rainforests of the Amazon, and the plains of Australia in search of endangered plant species to propagate, drawn always to his most treasured plant, the water lily. To help save the pygmy lily, Nymphaea thermarum, a Rwandan species that grows in hot springs, he requested seeds from Germany’s Bonn University Botanical Gardens, where the horticulturists there had been unable to grow them to maturity. Magdalena approached the problem with his customary obsessive dedication, striking upon the solution one night as he was cooking tortellini: Maybe the lily needed more carbon dioxide to grow? He sowed the seeds on damp soil just one to two millimeters below water, allowing the emerging leaves to soak up air from the start. “I always say that obsession has a bad reputation,” he says, acknowledging his compulsive pursuit. “But I think obsession makes incredible things.”

That combination of doggedness and an intuitive approach to solving botanical mysteries has contributed to Magdalena’s breakthroughs, says Richard Barley, the director of gardens at Kew: “He is quite good at sticking to a problem over a period of time until the solution presents itself.”

More work remains than Magdalena can ever hope to accomplish. As many as 100,000 plant species remain undiscovered, according to estimates by Kew researchers. “We’re destroying whole ecosystems without knowing what we’re losing,” Magdalena says. In 2006, while surfing the web, he stumbled across a picture of a giant water lily in Bolivia. From his first glance he realized it differed from the two other known species of Victoria lilies. After years of research, including DNA analysis, Magdalena and a team of experts from Kew and Bolivia confirmed that the plant was indeed a third species: Victoria boliviana. Here was a plant with 10-foot-long leaves, a metaphorical elephant in the room that had escaped classification for more than a century. “It was a massive lesson for me,” Magdalena says. “What else is out there?”