Killer Clothing Was All the Rage In the 19th Century

Arsenic dresses, mercury hats, and flammable clothing caused a lot of pain.

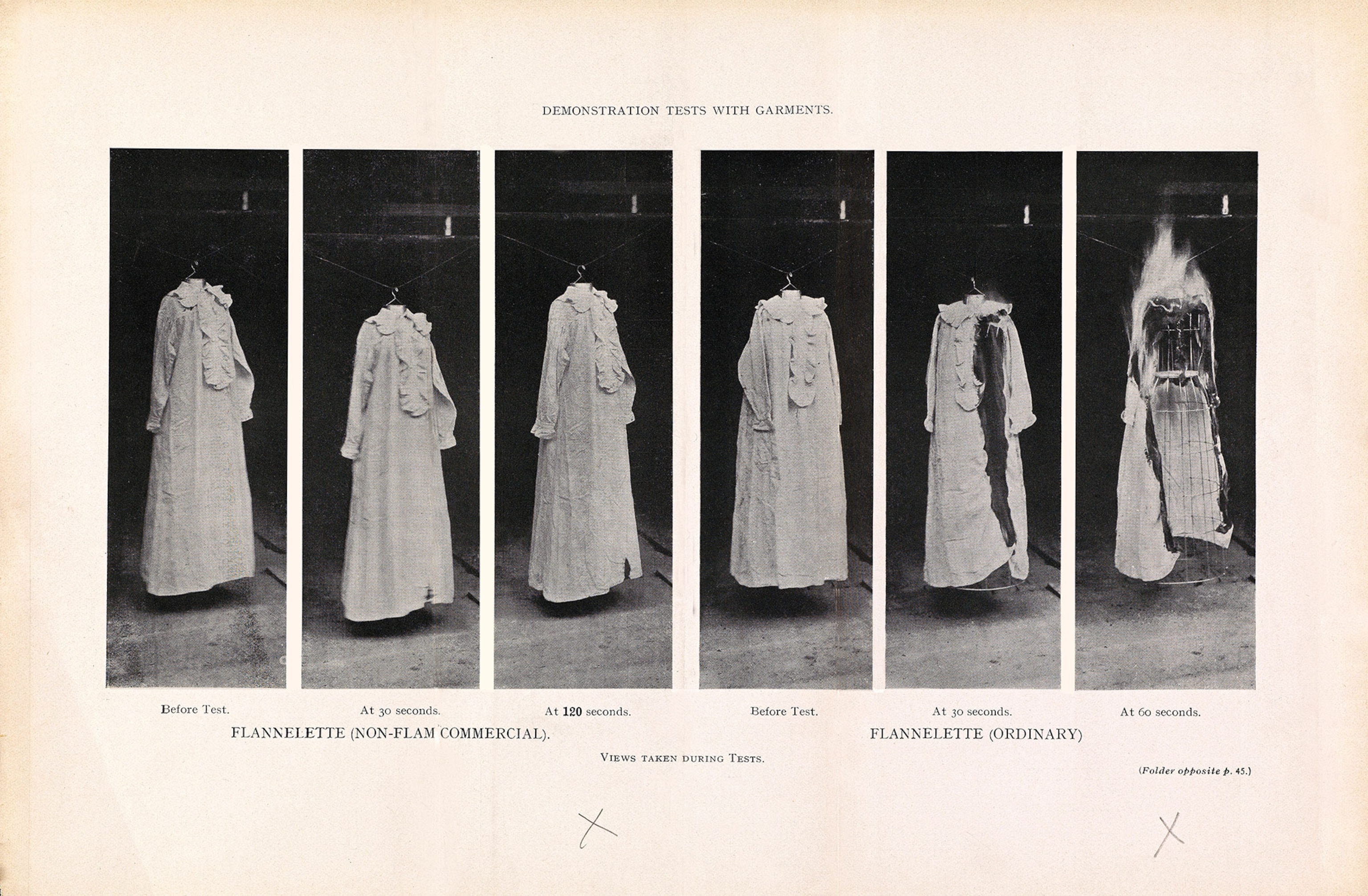

While sitting at home one afternoon in 1861, poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s wife, Fanny, caught fire. Her burns were so severe that she died the next day. According to her obituary, the fire had started when “a match or piece of lighted paper caught her dress.”

At the time, this wasn’t a peculiar way to die. In the days when candles, oil lamps, and fireplaces lit and heated American and European homes, women’s wide hoop skirts and flowing cotton and tulle dresses were a fire hazard, unlike men’s tighter-fitting wool clothes.

It wasn’t just dresses: Fashion at this time was riddled with dangers. Socks made with aniline dyes inflamed men’s feet and gave garment workers sores and even bladder cancer. Lead makeup damaged women’s wrist nerves so that they couldn’t raise their hands. Celluloid combs, which some women wore in their hair, exploded if they got too hot. In Pittsburgh, a newspaper reported that a man with a celluloid comb lost his life “While Caring for His Long Gray Beard.” In Brooklyn, a comb factory exploded.

In fact, some of the most fashionable clothing of the day was made using chemicals that are today considered too toxic to use—and it was the producers of this clothing, rather than the wearers, who suffered most of all.

Mercurial Maladies

Many people think that “mad as a hatter” refers to the mental and physical side effects hatmakers endured from using mercury in their craft. Though scholars dispute whether this is actually the origin of the phrase, many hatters did develop mercury poisoning. And even though the phrase has a certain levity to it, and while the Mad Hatter in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was silly and fun, the actual maladies hatmakers suffered were no joke—mercury poisoning was debilitating and deadly.

In the 18th and 19th century, a lot of men’s felt hats were made using hare and rabbit fur. In order to make this fur stick together to form felt, hatters brushed it with mercury.

“It was extremely toxic,” says Alison Matthews David, author of Fashion Victims: The Dangers of Dress Past and Present. “Especially if you inhale it. It goes straight to your brain.”

One of the first symptoms was neuromotor problems, like trembling. In the hat-making town of Danbury, Connecticut, this was known as the “Danbury shakes.”

Then there were the psychological problems. “You would become very shy, very paranoid,” Matthews David says. When medical examiners visited hatters to document their symptoms, hatters “thought they were being observed, and they would throw down their tools and get angry and have outbursts.”

Many hatters also developed cardiorespiratory problems, lost their teeth, and died at early ages.

Although these effects were documented, many viewed them as the hazards that one had to accept with the job. And besides, the mercury only affected the hatters—not the men who wore the hats, who were protected by the hats’ lining.

“There was always kind of a bit of a pushback from the hatters themselves,” Matthews David says of these dangerous working conditions. “But really, honestly, the only thing that made [mercury hatmaking] disappear was the fact that men’s hats went out of fashion in the 1960s. That’s really when it dies. It was never banned in Britain.”

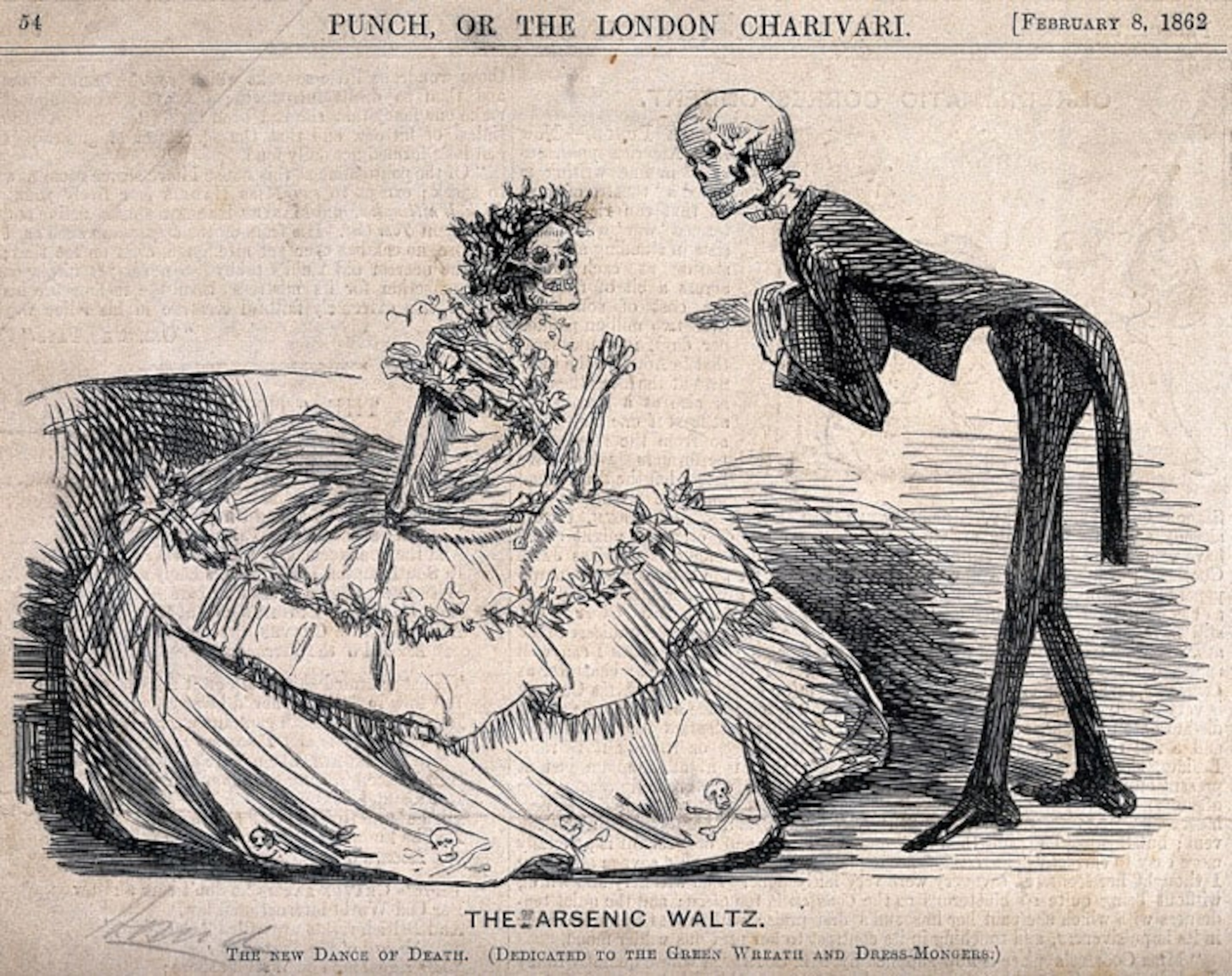

Arsenic and Old Lace

Arsenic was everywhere in Victorian Britain. Although it was known to be used as a murder weapon, the cheap, natural element was used in candles, curtains, and wallpaper, writes James C. Whorton in The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain Was Poisoned at Home, Work, and Play.

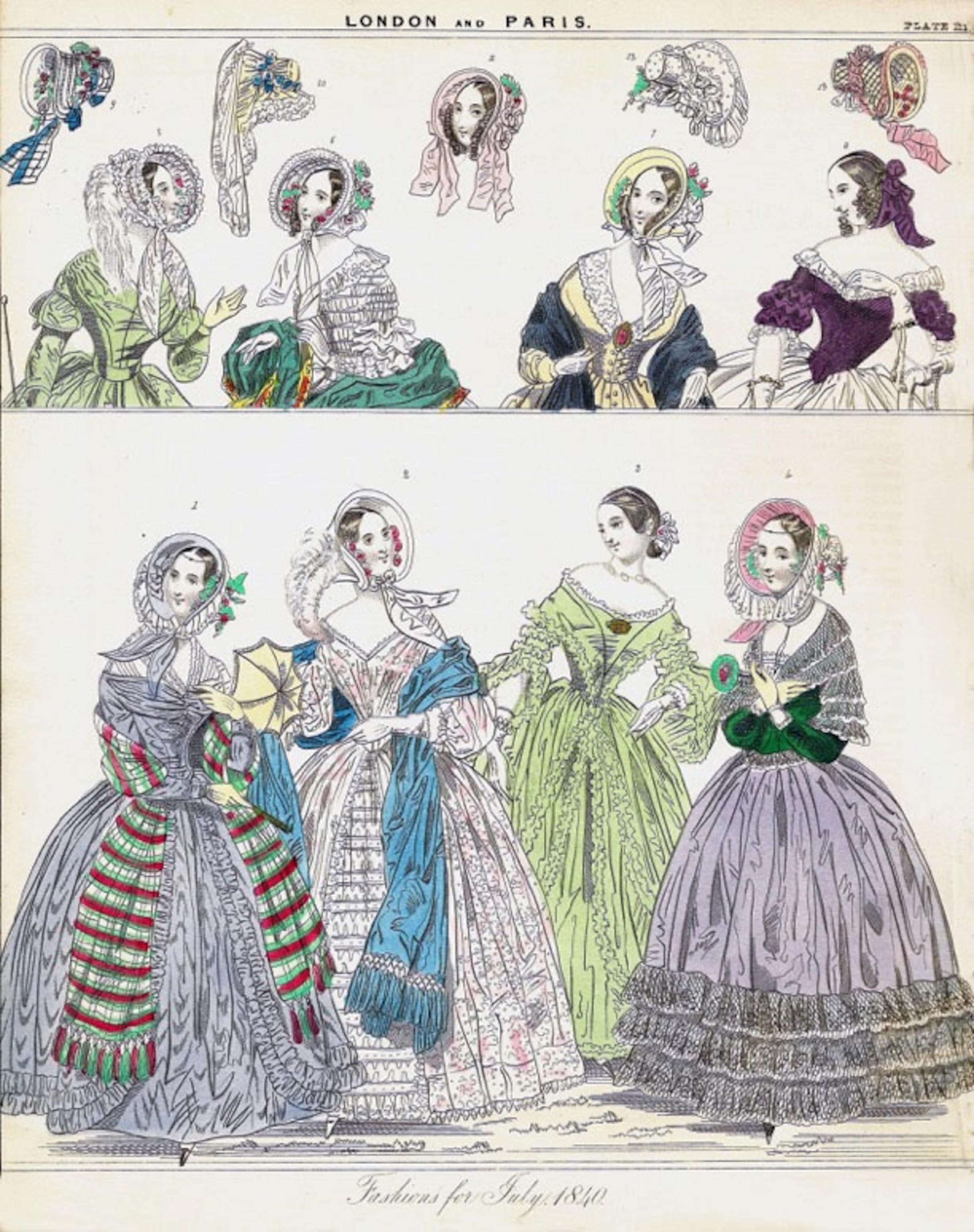

Because it dyed fabric bright green, arsenic also ended up in dresses, gloves, shoes, and artificial flower wreaths that women used to decorate their hair and clothes.

The wreaths in particular could cause rashes for women who wore them. But like mercury hats, arsenic fashions were most dangerous for the people who manufactured them, says Matthews David.

For example, in 1861, a 19-year-old artificial flower maker named Matilda Scheurer—whose job involved dusting flowers with green, arsenic-laced powder—died a violent and colorful death. She convulsed, vomited, and foamed at the mouth. Her bile was green, and so were her fingernails and the whites of her eye. An autopsy found arsenic in her stomach, liver, and lungs.

Articles about Scheurer’s death and the plight of artificial flower makers raised public awareness about arsenic in fashion. The British Medical Journal wrote that the arsenic-wearing woman “carries in her skirts poison enough to slay the whole of the admirers she may meet with in half a dozen ball-rooms.” In the mid-to-late 1800s, sensational claims like these began to turn public opinion against this deadly shade of green.

Safety in Fashion

Public concern over arsenic helped phase it out of fashion—Scandinavia, France, and Germany banned the pigment (Britain did not).

The move away from arsenic was hastened by the invention of synthetic dyes, which made it “easy to let arsenic go,” according to Elizabeth Semmelhack, senior curator at the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, Canada. (The museum’s “Fashion Victims” exhibit, which Matthews David collaborated on, is on view through January.)

This raises interesting questions about fashion today. While arsenic dresses might seem like bizarre relics of a more brutal age, killer fashion is still very much in vogue. In 2009, Turkey banned sandblasting—the practice of spraying denim with sand to give it a fashionable distressed look—because workers were developing silicosis from breathing in sand.

“It’s not a curable disease,” Matthews David says of silicosis. “If you have sand in your lungs it will kill you.”

Yet when a dangerous production method is banned in one country—and when the demand for the clothing that method produces remains high—then production typically moves somewhere else (or continues despite the ban). Last year, Al Jazeera found that some Chinese factories were sandblasting clothes.

In the 1800s, men who wore mercury hats or women who wore arsenic-laced clothing and accessories might have seen the people who produced these items on the streets of London, or read about them in the local paper. But in a globalized economy, many of us don’t see the deadly effects that our fashion choices have on others.