In exile, Hebrews found hope in Prophet Ezekiel’s visions

The prophet's visions after the fall of Jerusalem led to the creation of a new Jewish identity.

A prophet during the Babylonian exile, Ezekiel’s hopeful visions gave rise to a Jewish identity that extended beyond geographical and political borders.

With the fall of Jerusalem and forceful deportation of citizens from Judah to Babylon, the Hebrew nation was shocked and in a spiritual crisis. Why had God allowed this catastrophe to happen? How could Torah observance, including worship at the Temple, be sustained when the Temple lay in ruins? Would this mark the end of the great story of Israel?

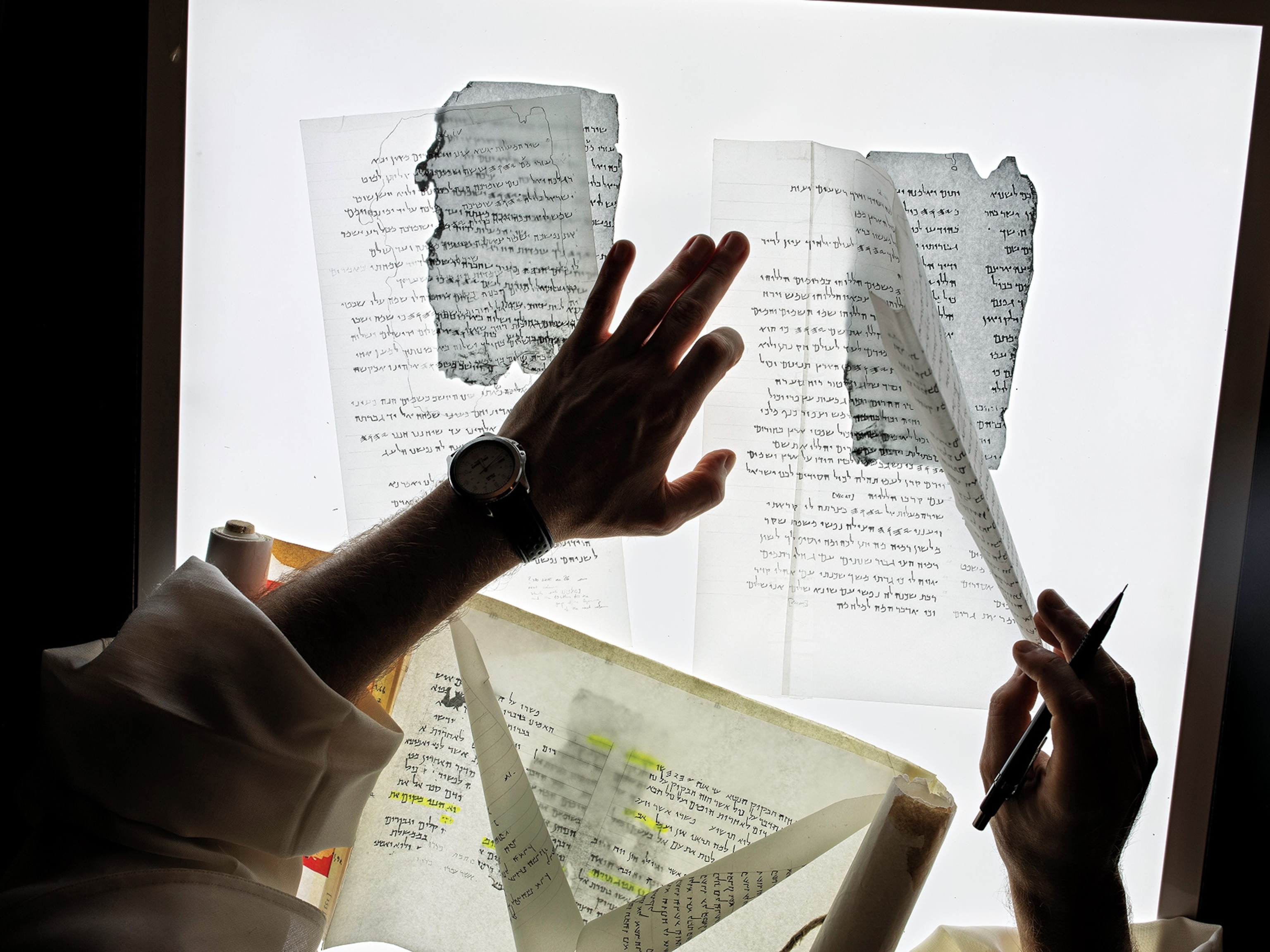

These and other questions were addressed by the prophet Ezekiel, son of a Zadokite priest who ministered to refugees during the exile. As a “sentinel for the house of Israel” (Ezekiel 3:17), Ezekiel had repeatedly warned of God’s pending penalty for Judah’s transgressions, including its fondness for idolatry (Ezekiel 5:7-10). Now that this punishment had come to pass, Ezekiel’s message turned to one of hope.

In his visions, he saw Jerusalem, its Temple, and its kingdom restored to their former glory; his detailed description of the future Temple, provided by an angel serving as a guide, would later be consulted by the actual builders of the Second Temple (Ezekiel 40-42). The day would come, Ezekiel foretold, when God’s dwelling place would once again be among them, when “I will be their God, and they shall be my people” (Ezekiel 37:27). Ezekiel’s gripping visions convinced his audience that the covenant was not broken, and that in due course, God would shepherd his people back to Israel.

Learn which religions in the Middle East are under threat.

This promise gave a new impetus to the need to preserve Hebrew customs and practices while the people lived in a foreign land. In fact, scholars believe that the Babylonian exile marks a crucial phase in the effort, begun by King Josiah many years earlier, to compile the many strands of Jewish history, ritual, and law into one comprehensive set of books. These books—Hebrew Scripture—would enable families to retain their unique identity and continue the rich liturgical life of their fathers and forefathers. Hence, from this time forward, modern scholars speak of the Hebrew nation as “Jews” (or Yehudim, possibly derived from “Judean”) and refer to “Judaism” as a community in religious terms, no longer bound to a particular political entity or geographical location.