These extreme stunts aren’t just magic tricks—they’re a religious experience

Eating glass. Fire walking. Sword swallowing. These acts that shock and delight have roots in the real and mythical practices of Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist, and Jain ascetics.

When Pallaniyammal Sanmugam was pregnant with her second son, her gynecologist advised she would have to undergo a cesarean section. Believing a vaginal delivery would be safer for both her and her baby, Sanmugam prayed to the Hindu god Karthikeya, promising that if she delivered a healthy baby through vaginal delivery, she would express her gratitude by piercing a trident through her body during Panguni Uthiram, a Hindu festival where devotees pierce their bodies with spikes, rods, and needles to pay respects to the god and thank him for fulfilled wishes. Soon, Sanmugam’s wish, too, was fulfilled.

“The following year, I had a trident pierced through my abdomen. I’ve done it 13 times so far, and each time, I’ve received what I’d asked for. If my body cooperates, I’ll do it at least thrice again,” says Sanmugam, 50. “It does not hurt. Even when they remove the trident, the bleeding stops the moment you apply some [holy ash] to your skin. The holes, too, close on their own in a week.”

American magician David Blaine explores these acts of magic and devotion in his new series, David Blaine Do Not Attempt. The docuseries, produced by Imagine Documentaries, premieres on National Geographic on March 23 and streams next day on Disney+ and Hulu.

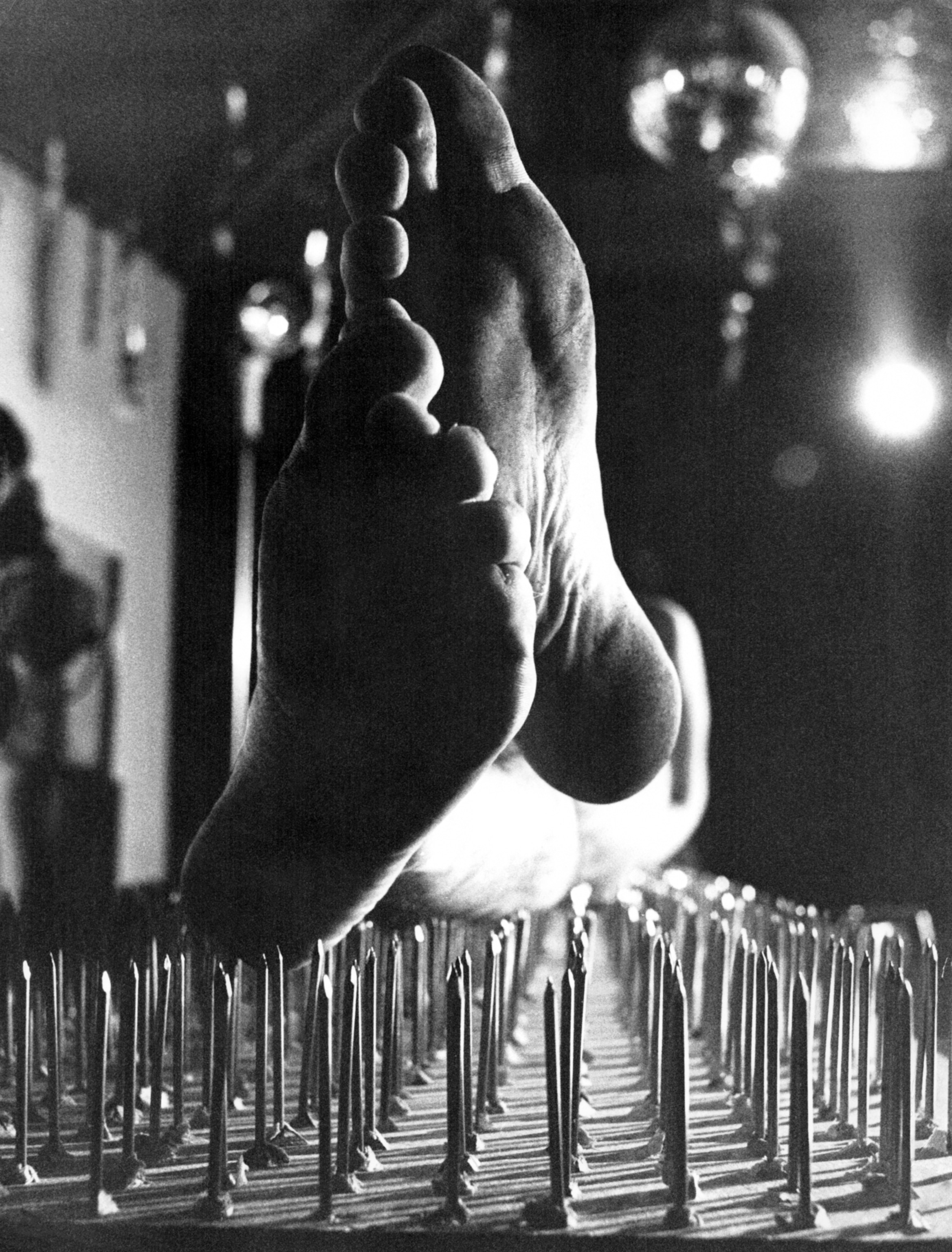

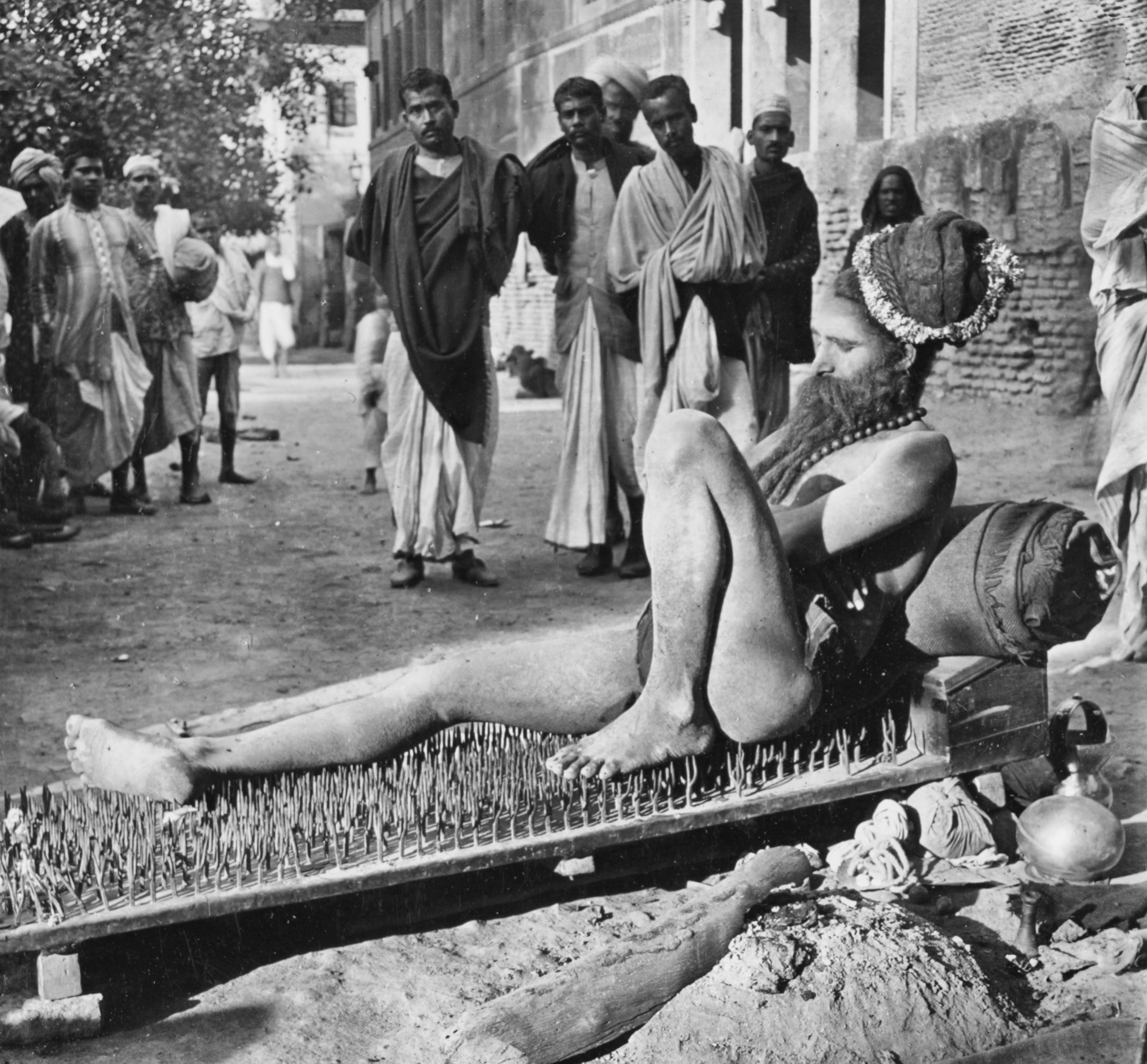

Panguni Uthiram is not the only religious festival in India where such extreme acts of devotion are performed. During Gajan, a pre-harvest festival in India’s West Bengal, men pierce themselves with iron rods, arrows, and hooks, praying for healthy crops. Daredevil acts also include rituals with fire, and lying on a bed of nails. Thaipusam, another Hindu festival, includes rituals where participants express their devotion by walking over burning coals and piercing various body parts, including their skin, tongue, and cheeks. During Garuda Thookkam, devotees suspend themselves from a tall pedestal-like structure through sharp metal hooks piercing their bodies. And during Thimthi, which is celebrated in India and other nations, including Fiji, Singapore, and Sri Lanka, devotees, including children, walk barefoot through fire pits.

“It is not magic. It is faith,” says devotee Ram Lakhsmi Tevar, 39. “People push rods and tridents through their bodies. They pull auto rickshaws, cars, and tempos through hooks pierced into their backs. …God will never let them get injured.”

Thousands of years of religion and magic in India

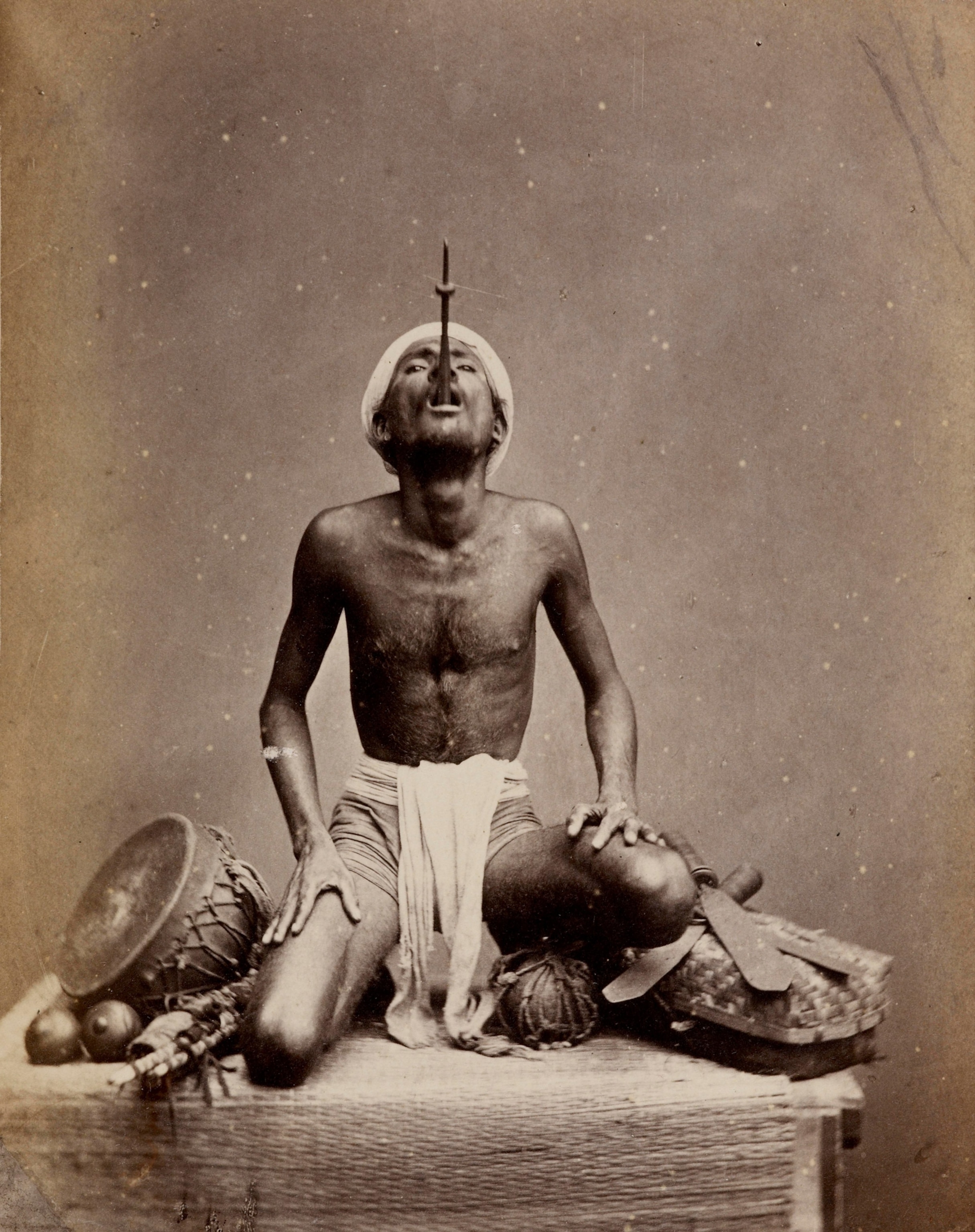

Religion and magic in India are closely connected, feeding off each other and reinforcing each other, says John Zubrzycki, an Australian historian and author of Jadoowallahs, Jugglers and Jinns: A Magician History of India. He adds that numerous magic tricks─cutting and restoring the tongue, being buried under the ground, fire walking, and restoring severed limbs─have their antecedents in the real and mythical practices of Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist, and Jain ascetics.

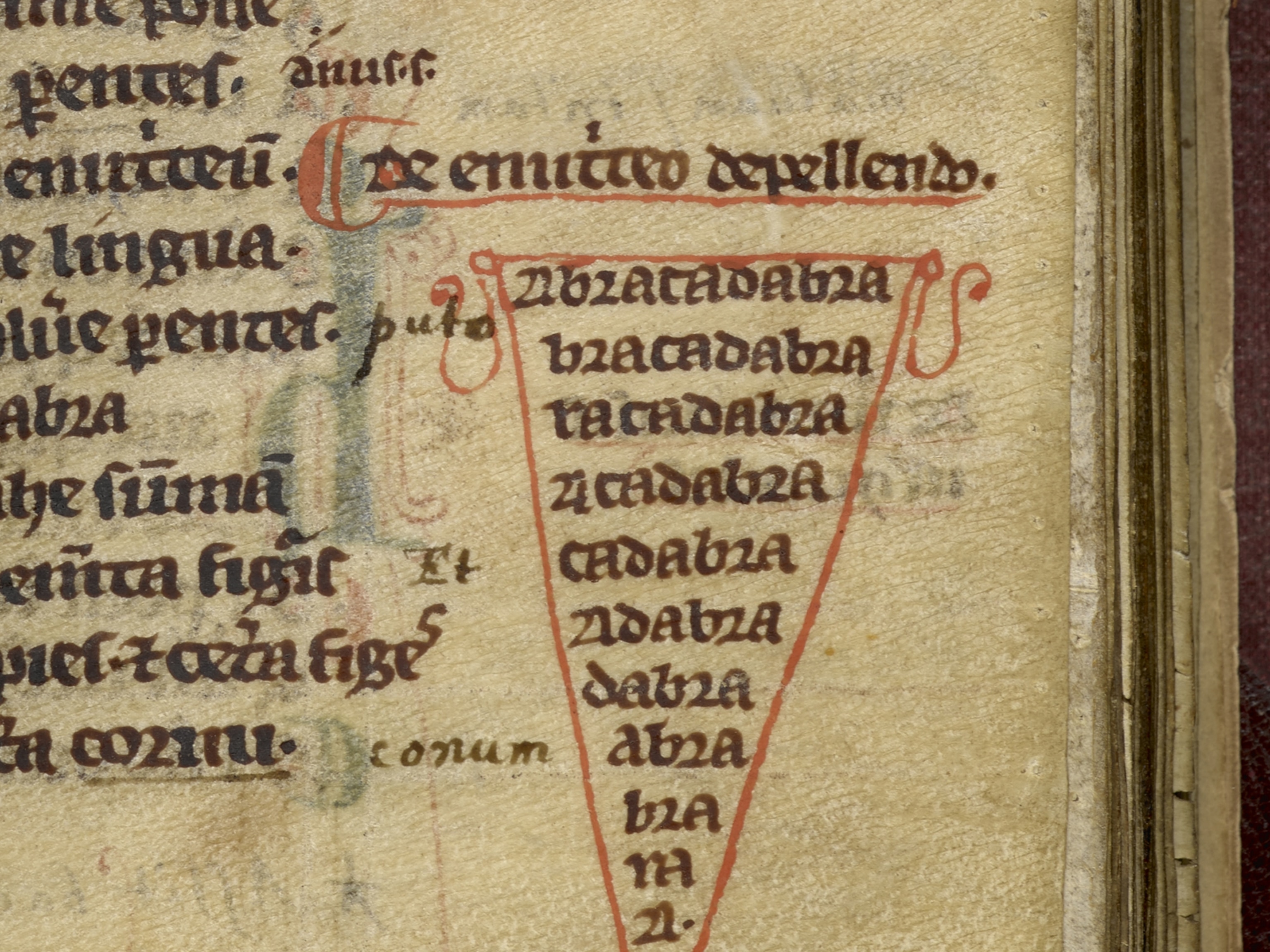

Sword swallowing, for example, is a 4,000-year-old Indian tradition developed by Indian priests, a ritual symbolizing spiritual power and connection with the gods. Now, it is also a performance art that has spread to several other countries. In the 1970s, the Swami Mantra, an anthology of magazines ‘Swami’ and ‘Mantra’, helped spread these acts by outlining several religion-based magic tricks including how to swallow razor blades, eat glass light bulbs, and pass silver needles from eye to eye, among others.

“The relationship between religion and magic [in India] goes back to the time of the Vedas which were composed between 1700 and 1500 BCE,” says Zubrzycki. The Atharvaveda, known as the oldest literary monument of Indian medicine, refers to nomadic holy men who practised exorcism, breath control, ritual dancing, and could place curses on their opponents.

Magic has also been a part of India's religious rituals and courtly life for centuries, he adds. For example, the Buddhist Jataka stories of the sixth century BCE contain many references to snake charmers and sword swallowers. Hindu and Muslim nobles often employed illusionists, mountebanks, jesters, buffoons, and clowns to entertain their guests, ministers of the court, the women of the harem, and ambassadors from distant lands. These performers were also an integral feature of festivals, religious rituals, and secular ceremonies.

Today, at the beginning of their performances, Hindu magicians often pay tribute to Indra, the god of magic, Zubrzyck states. Their audiences know the magician’s act is based on trickery, but invoking Indra insinuates that it could be more.

Magic and religion in India today

Sanmugam says that she was nine years old when she first had a trident pierced through her body. Often, in cases of physical ailments, the trident is pierced into the ailing body part. Over the years, Sanmugam says she has seen the act rid people of their physical, emotional, and financial troubles.

“My sister-in-law, she did not have a home of her own… She prayed that she would [pierce a trident through her body] every year for the rest of her life if her family was taken care of. She prayed to have a home of her own, and that her son studied well. Today, her son works as an engineer. He has built not one but seven houses,” says Sanmugam. “There’s no magic in this, it’s devotion.”

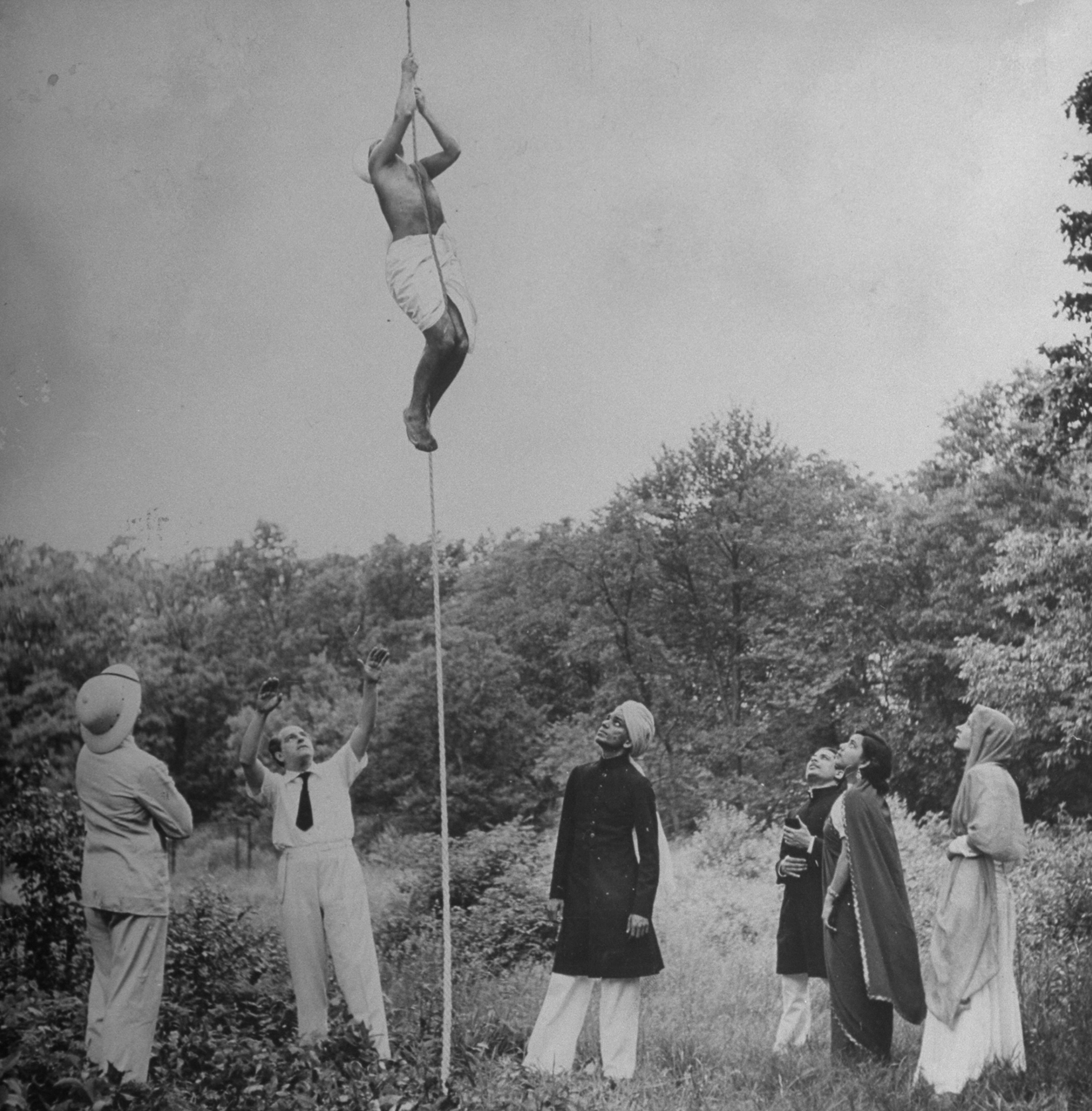

Not everyone sees magic and religion as inextricably intertwined. Ishamuddin Khan, a world-renowned Indian street magician, says that he is deeply religious, but his magic has nothing to do with his religion — that it's an art he has developed through years of practice. In 1995, Khan performed the Great Indian Rope Trick before a stunned audience in New Delhi. Khan was able to make a rope stand erect in the air, allowing a child to climb it. Khan’s feat made headlines around the world, and Britain’s Channel 4 ranked him and the rope trick 20th on its list of 50 Greatest Magic Tricks.

Back in New Delhi, however, people assumed that Khan had supernatural powers. The magician remembered when a businessman asked him to use his powers to stop his daughter from marrying an already married man.

“They think I have some special powers because I performed the rope trick while living in a slum. They do not believe that I worked hard for six years to master the trick,” says Khan. He adds that even the rich and educated believe the same, many of whom approach the magician after his shows, asking him to study their palms and predict their futures. “If I want, I can become a religious guru and a millionaire overnight,” he says.