Why the case of Ireland’s missing crown jewels remains unsolved after more than a century

Stored in a castle in the most guarded corners of Dublin, the jewels were taken from a locked strongbox that wasn’t forced open.

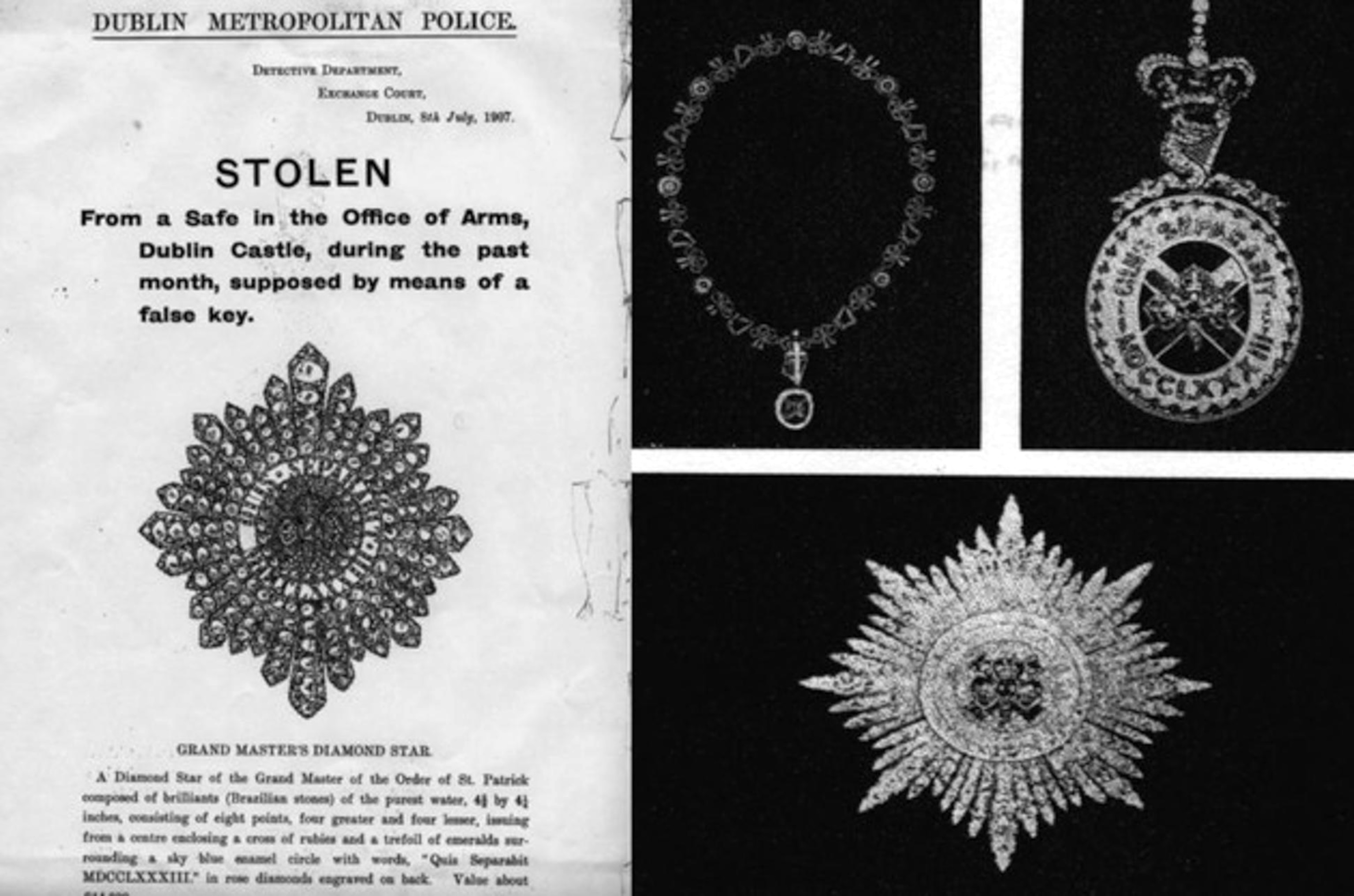

On July 6, 1907, Sir Arthur Vicars made a terrible discovery: the Irish crown jewels, which were kept under lock-and-key in his office at Dublin Castle, had been stolen. The jewels, owned by a group connected to the colonial British crown, were last seen June 11, so there was no telling when specifically they had vanished.

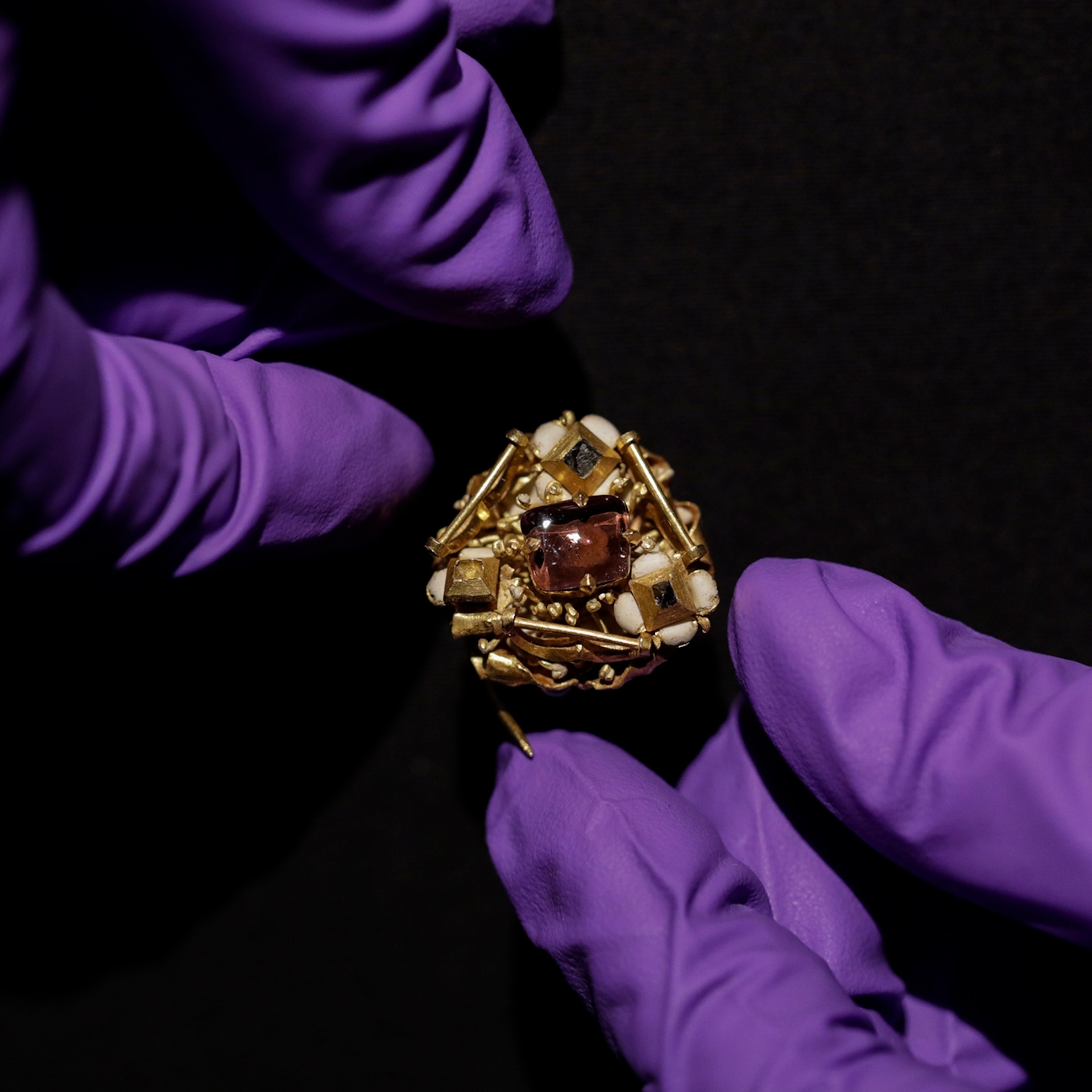

The collection included badges and collars that contained gems and precious stones, including emeralds, rubies, and brilliant Brazilian diamonds. Some at the time estimated the collection was worth as much as £50,000, amounting to $5 million today.

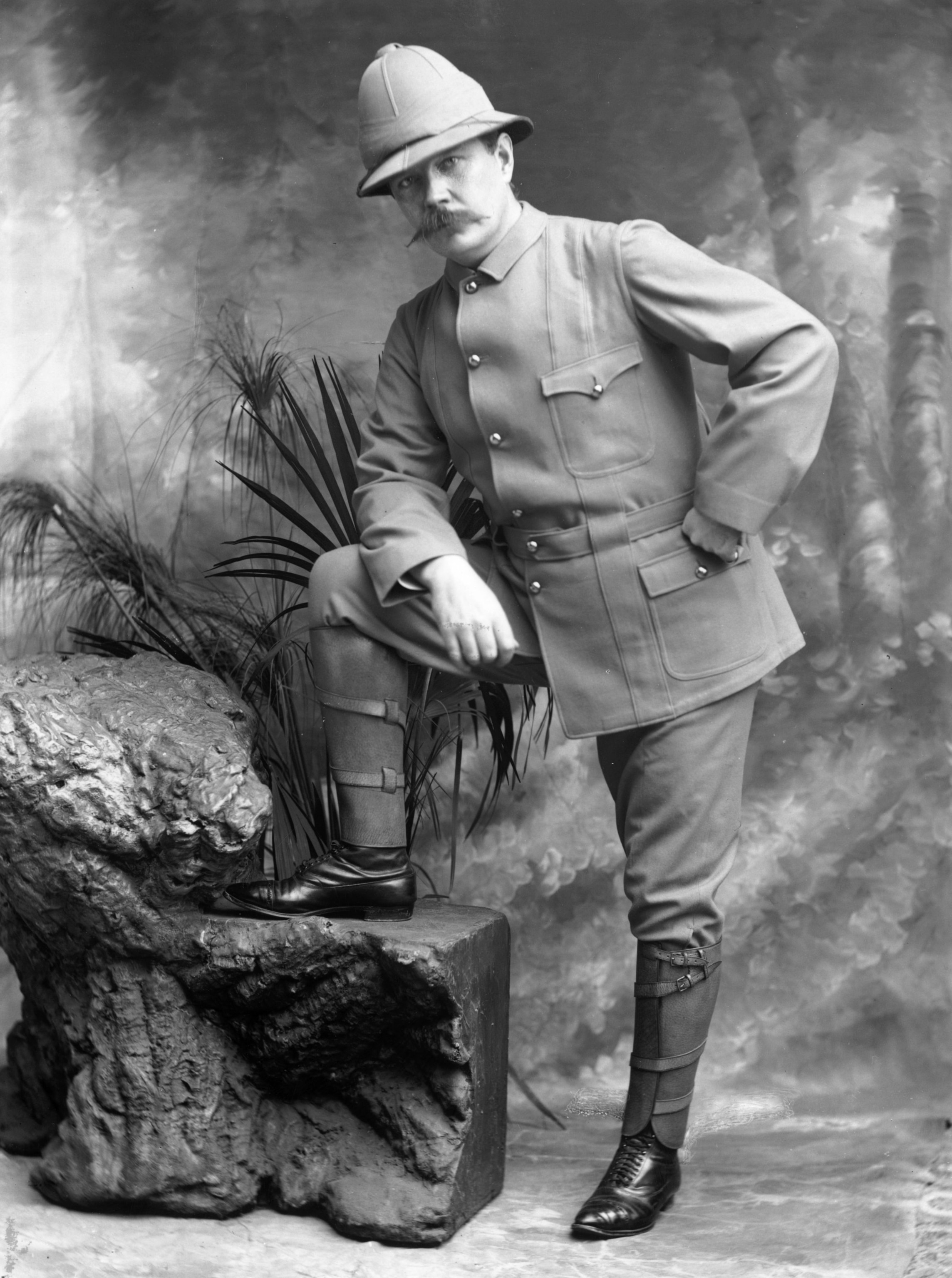

As Ulster King of Arms, Vicars was personally responsible for the jewel collection. The theft was a blow to his ego, career, and reputation––and it was a blow to Dublin Castle, the seat of British authority in Ireland.

News of the theft quickly spread, attracting international attention and sparking an investigation that would further humiliate Vicars, connect to some of the most notable celebrities of the period, and bring up more questions than answers. Most pressing: Who was behind the theft? And would the jewels ever be recovered?

A remarkable heist

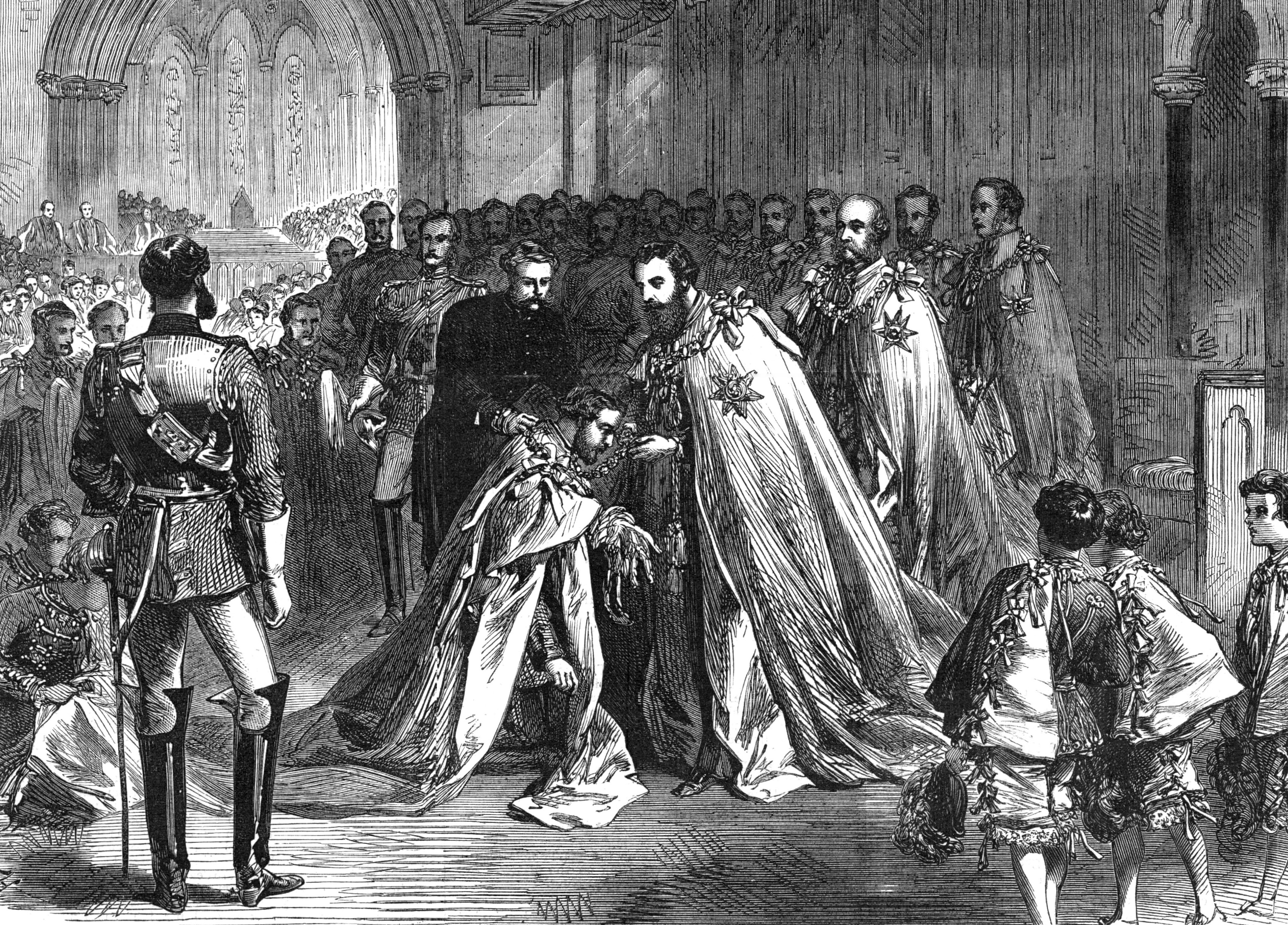

The stolen jewels were the ceremonial ornaments of the Order of St. Patrick, an elite Irish-based British order of chivalry. British king William IV had given the collection to the order in 1831, so that the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland—who also served as the order’s head––could wear them for ceremonies.

When Sir Arthur Vicars discovered that the jewels were missing, no one could quite believe it. “The news was so astounding that people at first were inclined to discredit it,” reported The Irish Times on July 9. Even Scotland Yard, which provided support in the investigation, initially speculated that the regalia had been “mislaid,” rather than burgled.

What made the theft so extraordinary was the thieves’ audacity in staging a heist at Dublin Castle, one of the best guarded corners of the city. The culprits would have had to sidestep patrolling police and officers to enter the building unnoticed.

More obstacles would have awaited the thieves inside Vicars’ office: he kept the jewels in a locked strongbox. The thieves apparently hadn’t forced it open, which means they must have used either a stolen or counterfeit key to simply unlock the safe and pocket the jewels.

The thieves’ ability to slip past security and unlock the safe raised an important question: Was it possible that it had been an inside job?

The creator of Sherlock Holmes took the case––sort of

Attention soon landed on Vicars, if not for his role in the theft, then for his failure to prevent it. Vicars also suspected that someone may have drugged him a week earlier, which could have given the thief an opportunity to copy his keys. More likely, Vicars probably had probably drank too much at one of the many private parties he threw at the castle, and someone took advantage of his drunken state.

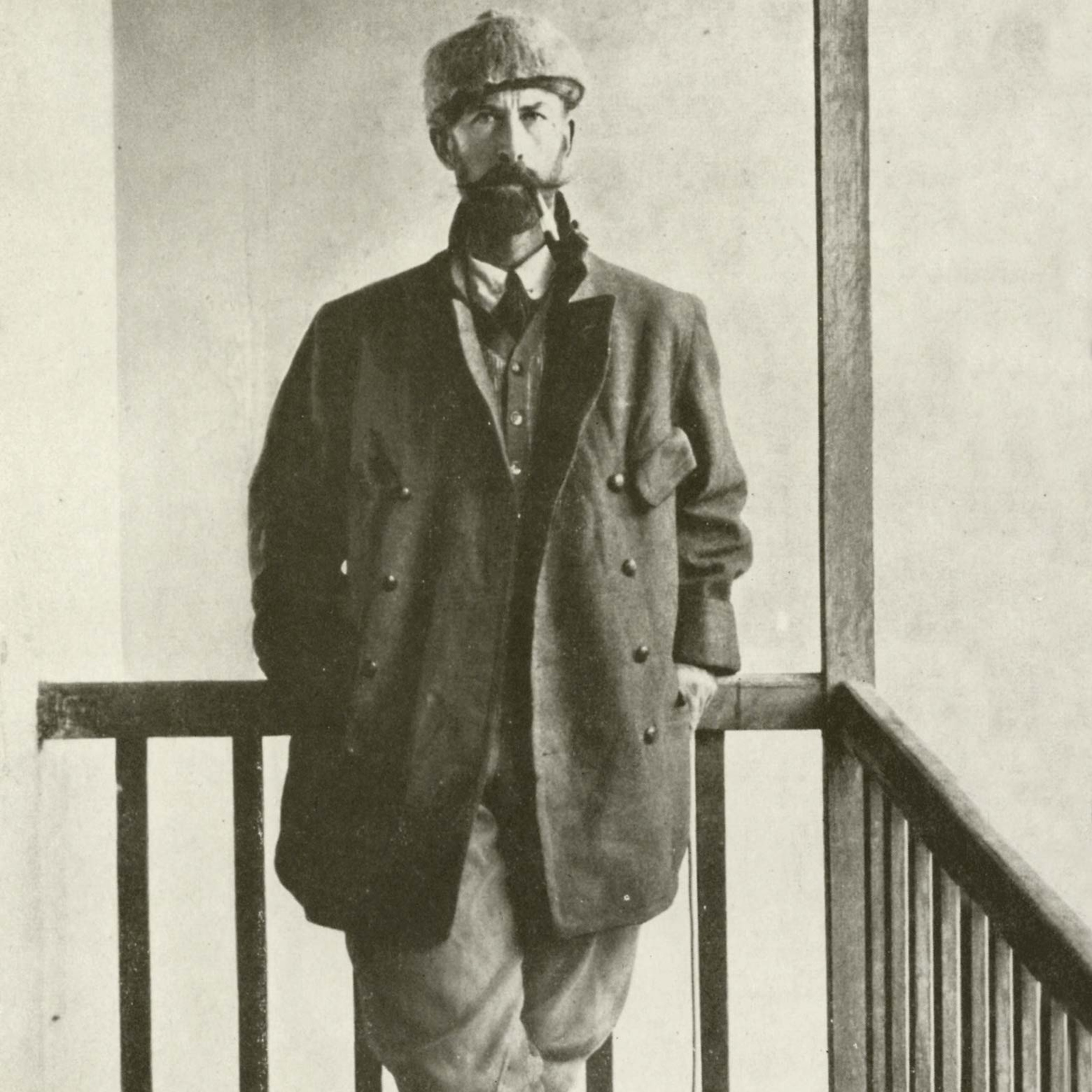

Vicars had at least one resolute ally: his cousin, the writer Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, whose Sherlock Holmes novels had made him a household name. Doyle reached out to his cousin and offered to do whatever he could to help.

Doyle may have been the creator of fiction’s greatest sleuth, but he brought “nothing of any practical value” to the investigation, says broadcaster and historian Myles Dungan, author of The Stealing of the Irish Crown Jewels: An Unsolved Crime. Instead, Doyle’s involvement was limited to poring over maps of the crime scene and supporting Vicars during the ordeal.

The investigation went cold

Officials seemingly made very little progress in identifying the culprit, even though investigators included the Dublin Metropolitan Police and Scotland Yard.

Not all of the people involved were professional investigators. A group of spiritualists conducted a séance and claimed that the jewels were hidden in a nearby cemetery. Authorities pursued the lead but didn’t find anything there.

A Viceregal Commission, which began in January 1908, didn’t fare much better. Instead of subpoenaing witnesses or investigating the actual crime, the commission honed in on Vicars and placed the blame squarely on his shoulders, accusing him of negligence.

Dishonored, Vicars lost his position at Dublin Castle, and the crime went unsolved.

The mystery birthed several theories

Even if the investigation didn’t solve the crime, Vicars had his own theory. The person behind the theft, he insisted, was a man by the name of Francis Shackleton.

A fixture of London and Dublin high society, Shackleton––the younger brother of arctic explorer Ernest Shackleton––served as Dublin Herald, a position in Vicars’ office. Moreover, Shackleton apparently had money troubles which a cache of extravagant jewels might have solved.

Shackleton thus had easy access to the jewels and, perhaps, even a motive. But he also had an alibi: Shackleton wasn’t in Dublin when Vicars realized the jewels were missing.

Other theories centered on the political climate of early 20th-century Ireland, when nationalists in the country were calling for “Home Rule,” or for Ireland to have self-government. British king Edward VII wondered if Irish nationalists had stolen the jewels in a targeted, anti-colonial heist.

That wasn’t the only theory bound up with debates over Home Rule. “One of the absurd theories is that the British state, concerned about the prospect of Home Rule, decided to take back ‘their’ jewels surreptitiously and organized the heist,” Dungan says.

Dungan points out that the question of Home Rule wouldn’t reach a crisis point in British politics for another five years, providing them little motivation to go to the trouble of coordinating a heist in 1907.

The public’s interest in the incident hasn’t diminished

According to Dungan, “There have been numerous stories since 1907 involving people coming forward with ‘information.’”

In 1998, an unknown person claimed the jewels were hidden on the grounds of Kilmorna House, Vicars’ country estate. It was a hoax.

There isn’t an official investigation into the theft today, but that hasn’t stopped armchair detectives from trying to crack the case. In September 2024, historian, television presenter, and podcast host Dan Snow called on his listeners to send in any tips they may have about the jewels’ whereabouts.

Dungan doesn’t believe we’ll ever find the jewels because there’s likely nothing left to find. “They’ve been long since broken up,” he speculates. “If you’ve ever been engaged, you might even be wearing one of the diamonds on your ring finger.”

Whatever actually happened to the jewels, their fate remains a tantalizing puzzle whose final pieces will always be missing.