Reclaiming an old medium to tell new stories of Native Americans

These artists are using a historic photography method to shape modern-day narratives.

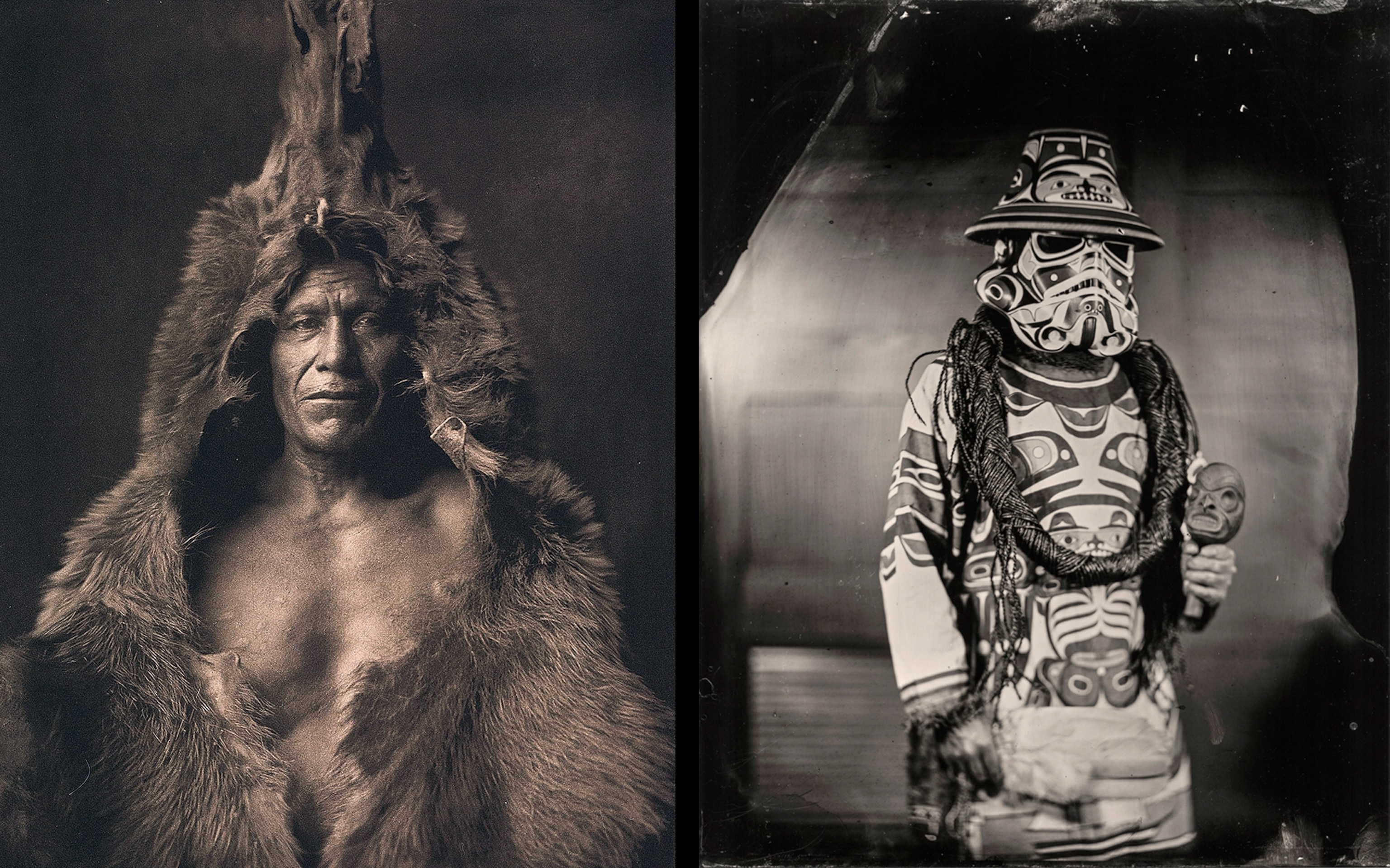

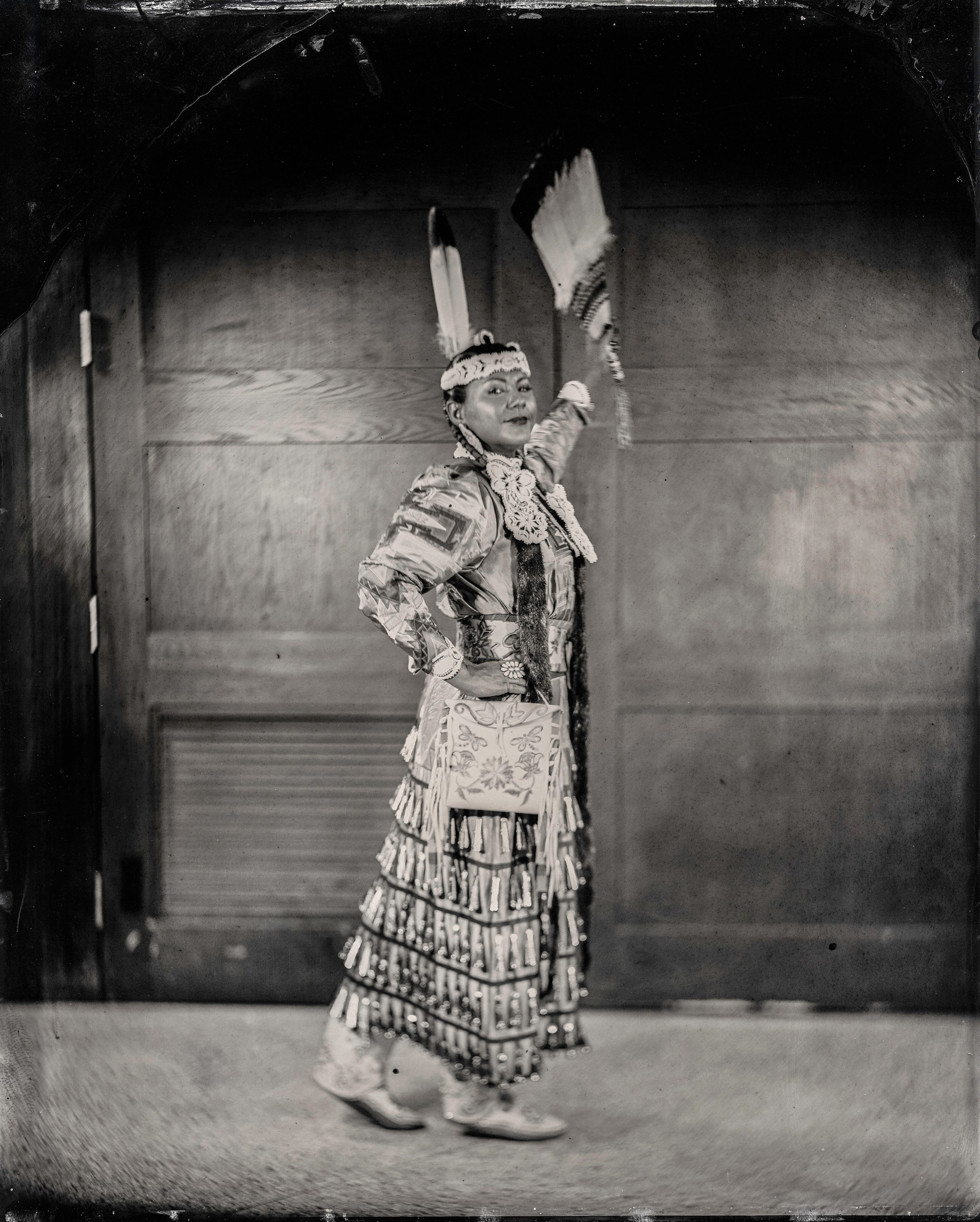

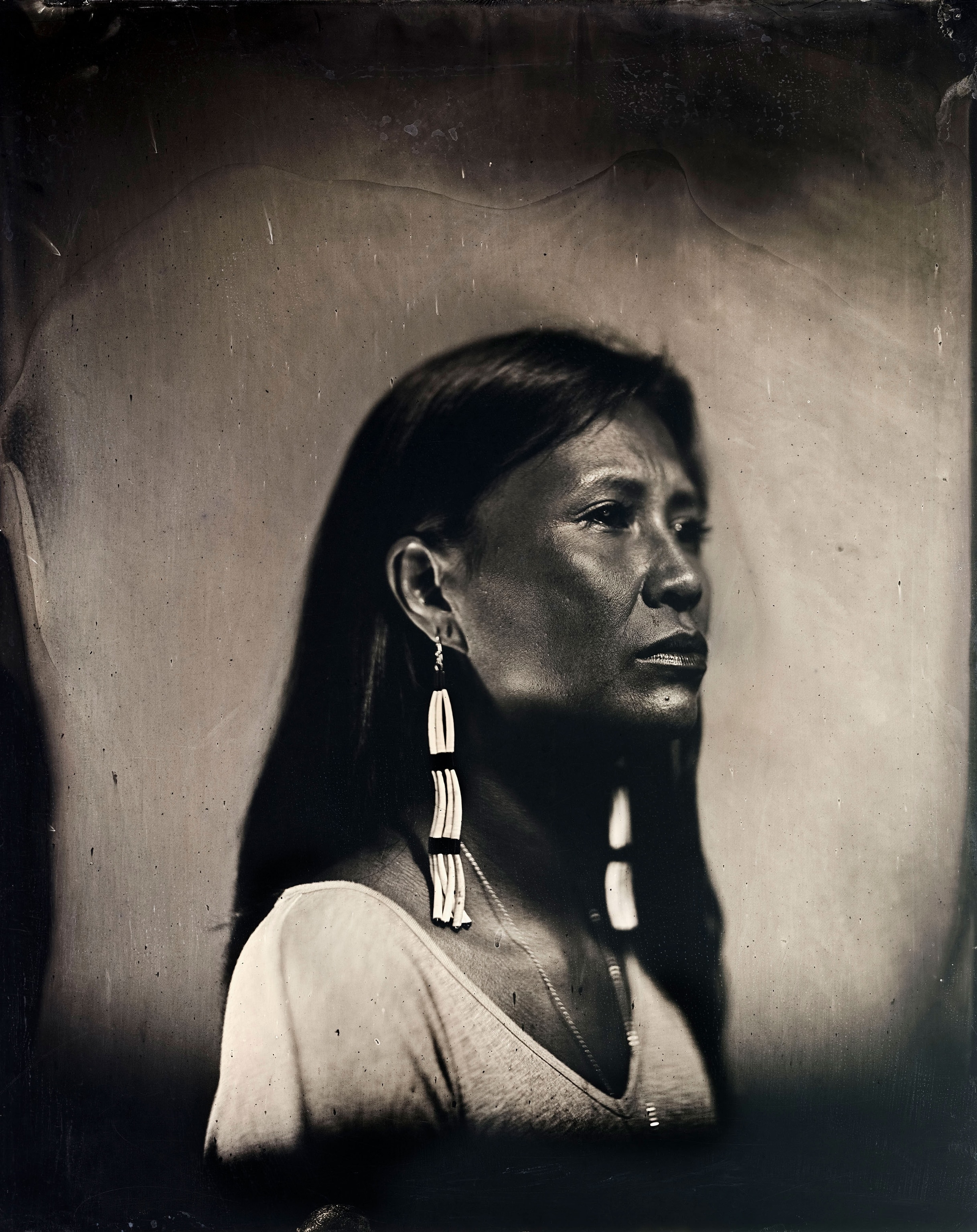

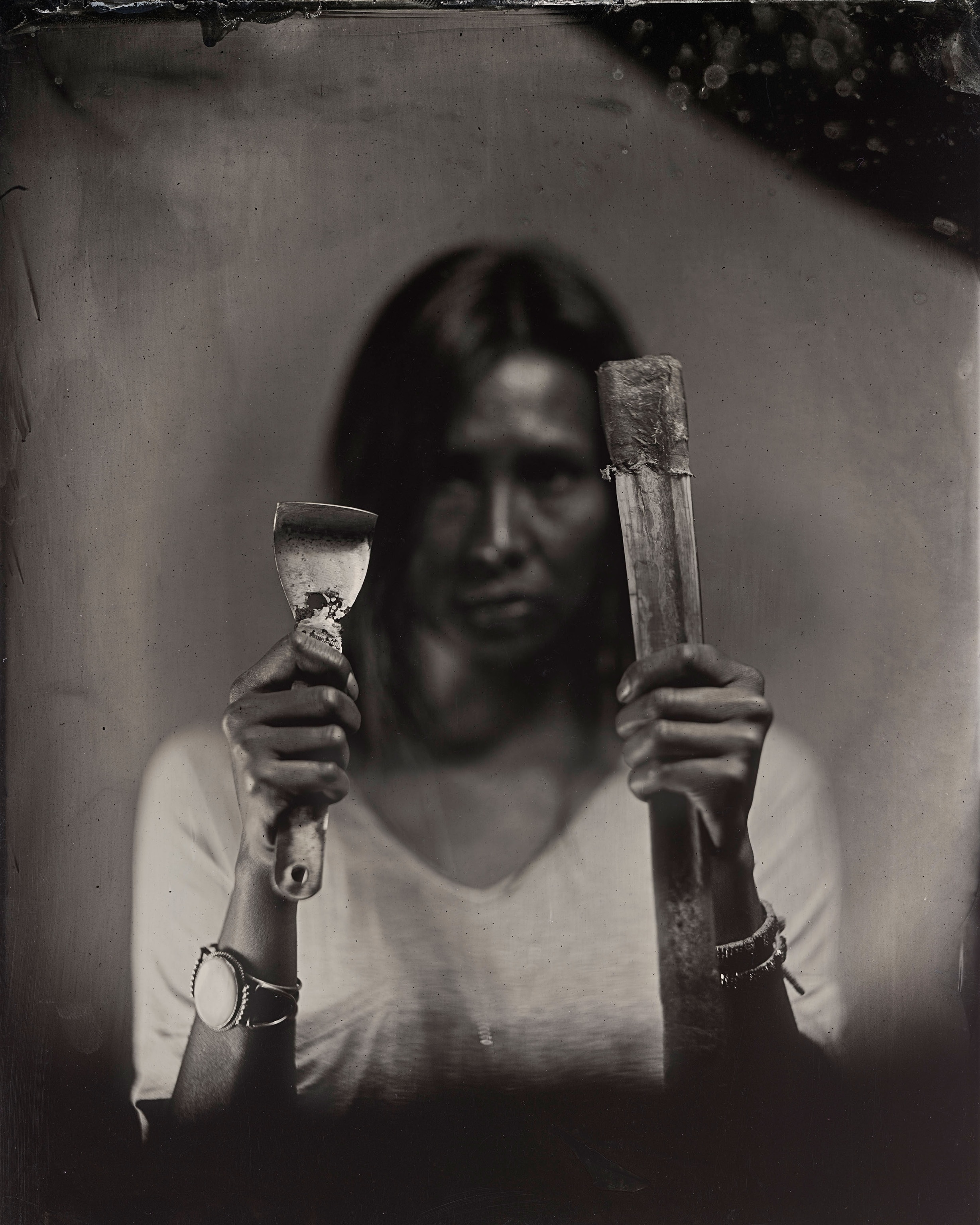

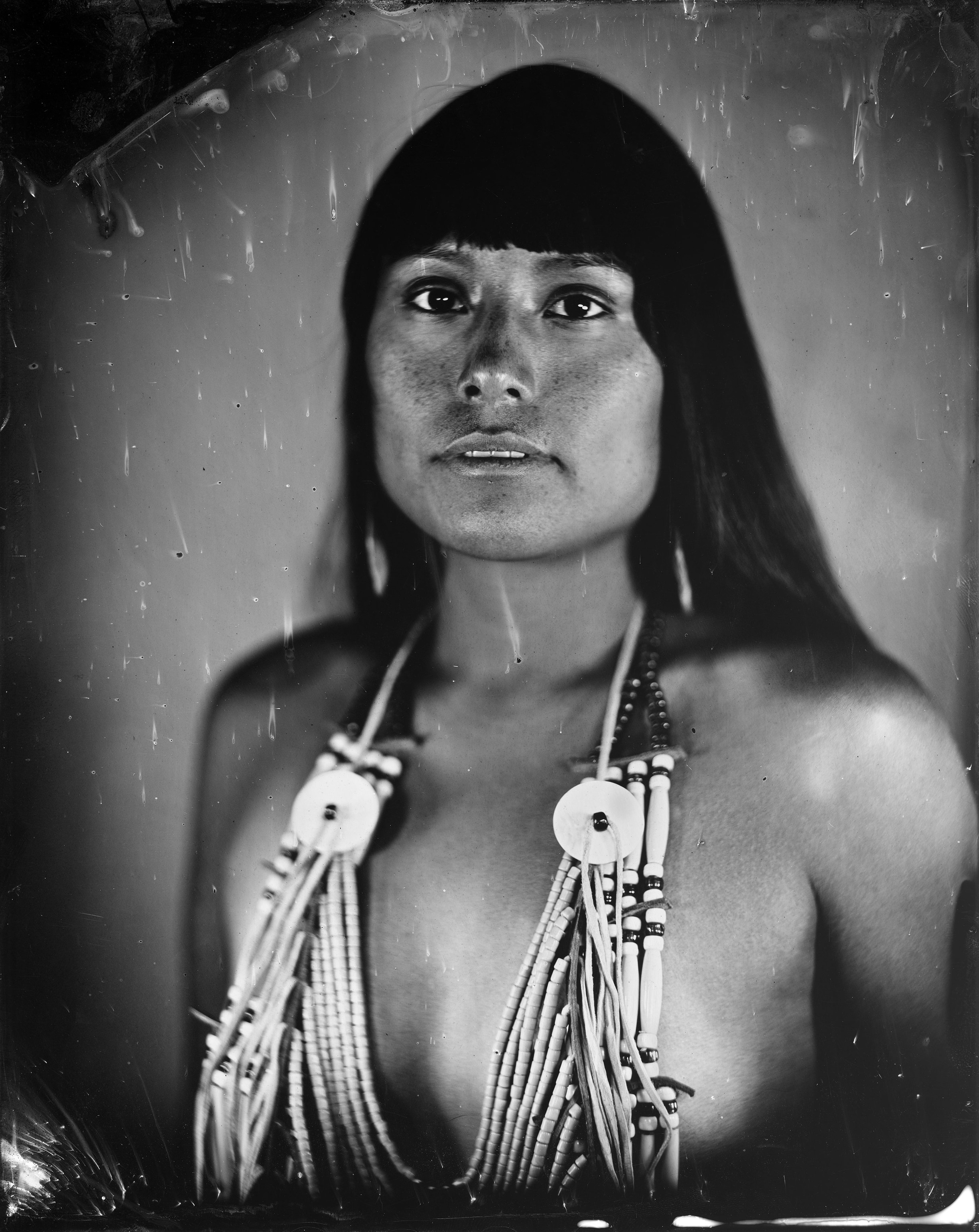

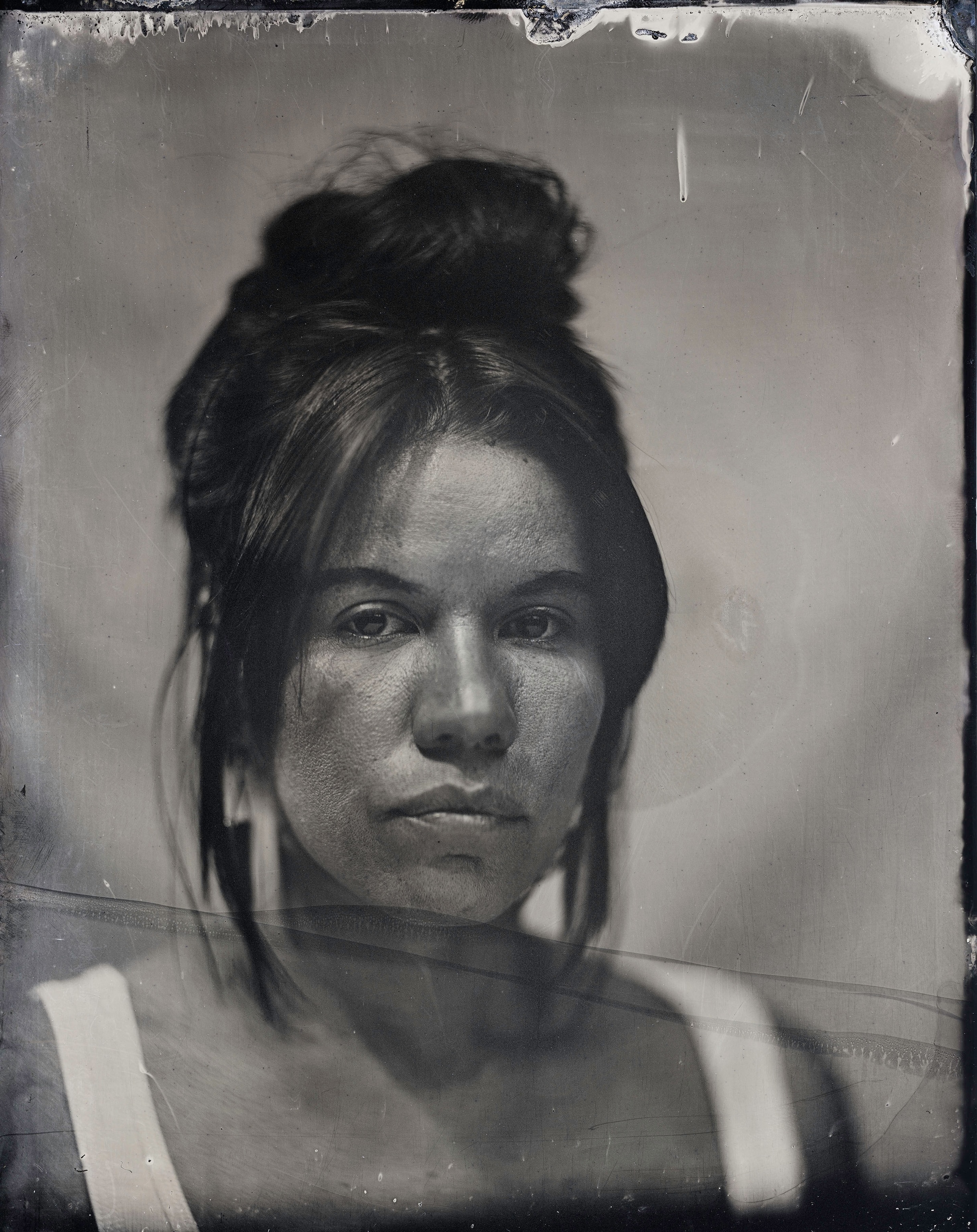

The portraits' revealing details—a baseball cap, tank top, wristwatch, down vest—contradict their old and withered appearance. What at first seem to be historic photographs are actually contemporary tintypes, images from respective projects about Native Americans from artists Will Wilson and Kali Spitzer.

Although their work employs an archaic medium, Wilson and Spitzer’s photographs have much to say about present-day Native American life. Wilson, a citizen of the Navajo Nation who is also of Welsh and Irish decent, sees his project as a collaboration with indigenous artists, arts professionals, and tribal leaders who, through their sessions, actively engage and dialogue with him. His evocative photographs counter longstanding stereotypes and distortions, contributing to “a re-imagined vision of who we are as Native people,” says Wilson.

Spitzer, whose father is Kaska Dena and mother is Jewish, moved back to British Columbia, Canada, to photograph the indigenous community in which she was raised. She sees her work as empowering Native Americans by allowing them to represent themselves as they would like to be seen. “Every photograph, every person has a story to tell, and I am supporting them to tell these stories through their portrait and voice recordings,” says Spitzer, who studied with Wilson at Santa Fe Community College. “I invite the viewer to recognize the different sides of these stories, including the pain, but most of all, the person’s spirit and perseverance.”

Wilson and Spitzer’s portraits provide insights not only about their subjects, but also about photography’s role in representing Native American life and culture. Their contemporary take on the tintype—a 19th-century photographic process in which a tin plate is blackened by paint, lacquer, or enamel and coated with a photographic emulsion—places them in dialogue with the problematic history of Native American imagery by white photographers.

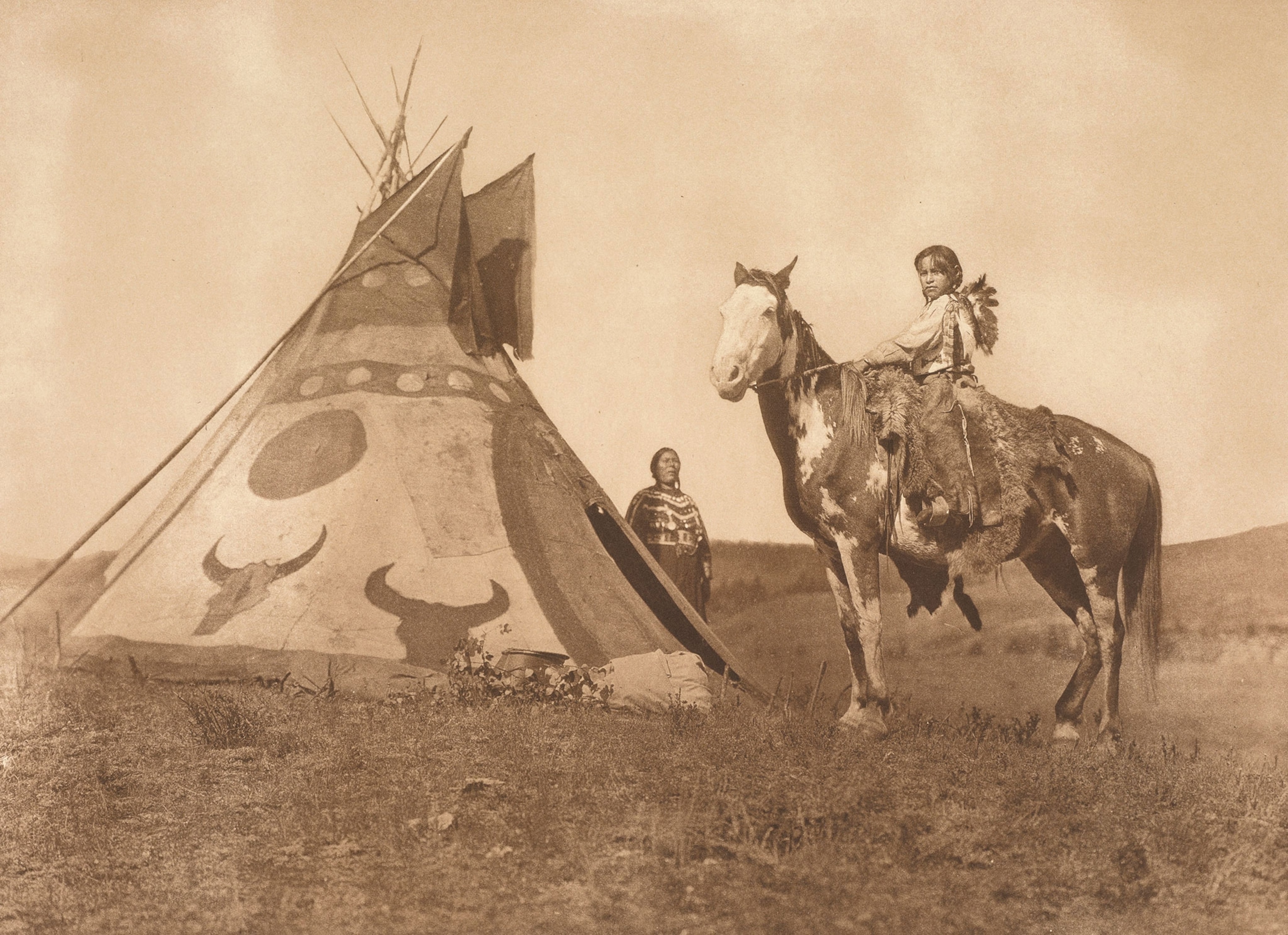

“I am impatient with the way that American culture remains enamored of one particular moment in a photographic exchange between Euro-American and Aboriginal American societies: the decades from 1907 to 1930 when photographer Edward S. Curtis produced his magisterial opus, The North American Indian,” says Wilson.

A landmark of Native American photography, Curtis’s monumental 20-volume work included more than 1,500 photographs taken in hundreds of indigenous communities across North America. The work, which meticulously documented aspects of Native American life that might otherwise have been lost to history, avoided the extreme stereotypes and caricatures of many cultural depictions of the period. But Curtis tended to represent his subjects as romanticized icons—often unnamed, isolated from the broader culture of the United States, and reinforcing white notions of indigenous Americans as exotic and fundamentally different. “For many people even today, Native people remain frozen in time in Curtis photos,” says Wilson.

Cognizant of this history, both Wilson and Spitzer emphasize the individuality and complexity of their subjects. Wilson sees his work in part as a response and challenge to Curtis’s photographs. As a 21st-century indigenous artist, he’s striving to supplant “the remarkable body of ethnographic material [Curtis] compiled with a contemporary vision of Native North America.” He encourages his sitters to bring items of significance to their portrait sessions, resulting in images that reflect the poignant details of their lives—from a manual typewriter and an open book to a violin and a 1960s peace sign.

Spitzer’s photographs, part of the series An Exploration of Resilience, challenge “preconceived notions of race, gender, and sexuality” in her community of primarily indigenous and mixed-heritage people, including gay, lesbian, non-binary, and transgender people historically ignored in cultural representations of Native Americans. She portrays her subjects as active, expressive, and self-possessed: They stare determinedly into the camera, cover their faces, remove garments, or nurse babies. Variations in clothing, hairstyles, and jewelry emphasize their diversity.

To further accentuate the personalities and humanity of the people they portray, both artists augment their photographs with sound and video. Insisting her subject be heard as well as seen, Spitzer includes voice recordings in museum installations of her work. Wilson transforms some of his portraits into “Talking Tintypes.” After downloading the free LAYAR app, viewers can scan these pictures with their cellphones or tablets and watch the subjects come to life in videos of them talking about their lives and experiences.

In the end, the medium that once enshrouded Native Americans in a haze of stereotypes and misconceptions has been reclaimed by Wilson and Spitzer. Their contemporary photographs recast their subjects not as exotic or nameless icons, preserved in time, but as complex and nuanced human beings.

“I want to show the general public who we are today; to bring light to our stories and create a safe space for us to be seen and heard as we define ourselves and make it clear how we want to be represented,” says Spitzer. “I want people to connect with us. I feel that this human connection can change how people see and treat us.”