How do Muslims celebrate Ramadan? Here are 5 unique traditions

From the sounding of the iftar cannon to lavish banquets, this is how Muslims mark the most sacred month of the year.

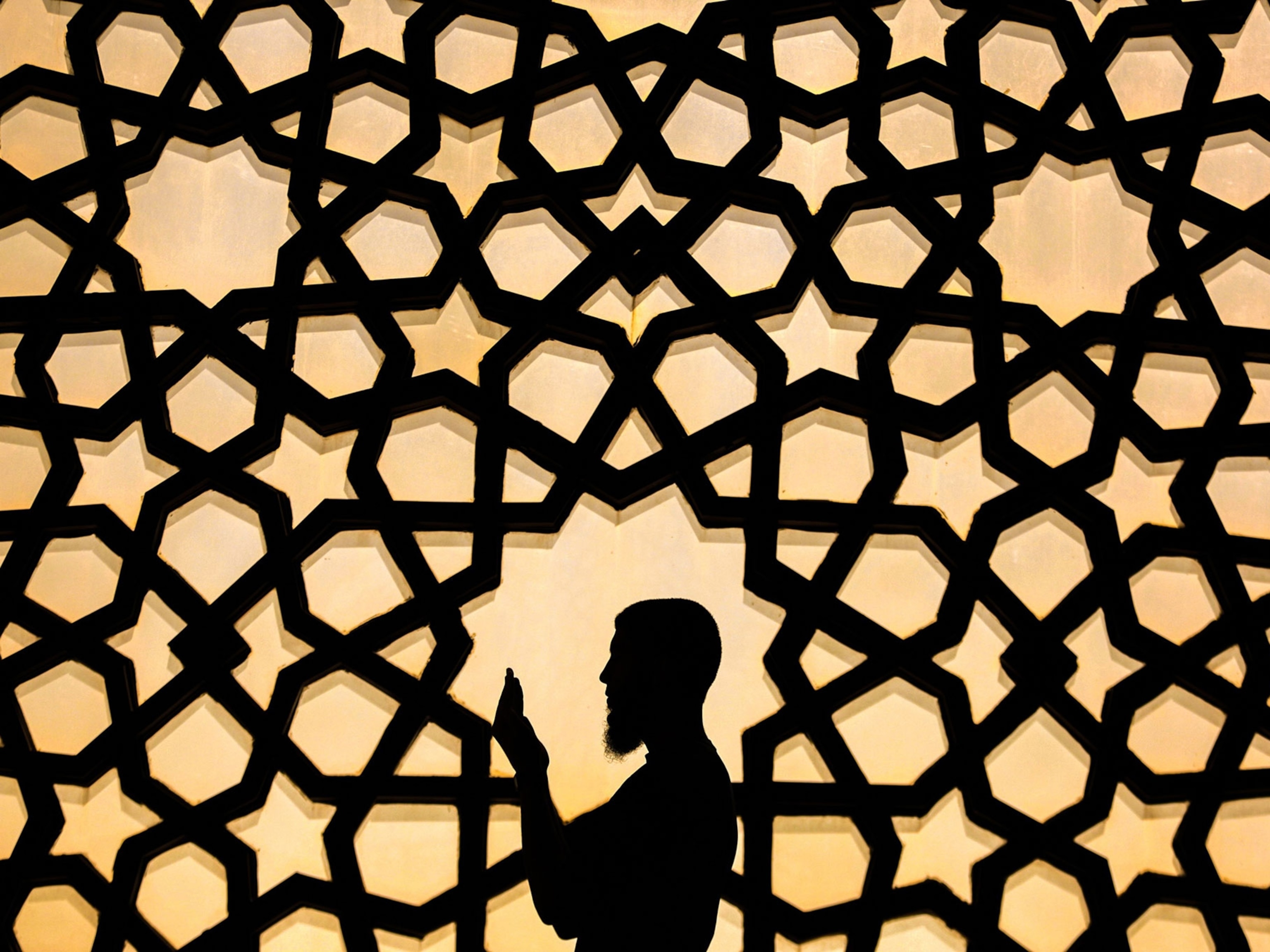

Muslims are welcoming the holy month of Ramadan—the most sacred time of the year in Islamic culture. Observed worldwide as a month of fasting and prayer, Ramadan has also been marked for centuries by a unique set of traditions that reflect the spirit of solidarity among people in the Islamic world.

From the booming cannons that hail the breaking of the fast to festive lantern-lit evenings, here are a few cherished Ramadan rituals.

1. The boom of the iftar cannon

The end of the day’s fast—as well the initial start of Ramadan—is hailed with a boom. Antique cannons fired by police mark iftar, or breaking the fast, at sunset.

Conflicting accounts detail the origin of this Ramadan ritual, though all point to Cairo. One follows that a 15th-century Mamluk dynasty sultan tested a cannon gifted to him, firing it at sunset during Ramadan. Cairo dwellers, it’s said, assumed it was an intentional ringing of the iftar.

Seeing the public response to the serendipitous action, the sultan ordered a shell to be fired every day at sunset to mark iftar. Live ammunition was used until 1859, when blanks were preferred for the densely populated city. The tradition first spread to the Levant, then to Baghdad by the end of 19th century, ultimately reaching the Gulf and North African countries.

2. An early wake-up call

Before there was an alarm clock, there was a masaharati, who sounds out the wakeup call. And the tradition still endures. During Ramadan, a masaharati is tasked with walking the streets to rouse Muslims for the suhoor—the pre-dawn meal before the fast begins—by playing a flute or beating a drum.

The first masaharati was Utbah bin Ishaq, a 7th-century governor of Egypt. As he walked through the streets of Cairo at night, he called out, “Servants of Allah, have suhoor, for there is blessing in suhoor.”

With time, the profession spread to other countries in the Islamic world, under different names and melodies. In Morocco, a naffar blows a trumpet to wake people.

In Yemen, the masaharati knocks door to door in a neighborhood. In the Levant, the role was so popular that each neighborhood had its own masaharati who roamed streets, beating a drum and calling out to the dwellers, “Wake up, sleeper, there’s no God but Allah the everlasting.”

3. Lighting the way

Lanterns have been synonymous with Ramadan for centuries, ushering in the holy month and figuratively lighting the way. The crescent moon and star, Islamic symbols, also feature prominently in decorations.

With the daily life changed radically as Muslims abstain from food and drink from dawn until sunset, Ramadan nights feature a full social life and entertainment as people meet in markets, cafes, and streets, where decorations and lights create a festive atmosphere for the month.

Each country has its own style of decor for Ramadan. The streets of Cairo are adorned with colorful fabrics, lamps, and lanterns. In North Africa, arabesque designs dominate. In the Gulf countries, colored lights and ornaments of eight-pointed stars and crescent moons hang from ceilings of shopping centers and lampposts.

While Ramadan has no formal colors, green, yellow, purple, and turquoise, hues that represent peace and spirituality, are common in decor.

(See a gallery of images showing how Muslims in America celebrate Ramadan.)

4. Banquets of plenty...

The communal banquets held in most Arab countries may best represent the fraternity of Islam during Ramadan. Compassion and empathy for those with fewer or little resources is a key tenet learned from fasting.

In Egypt charitable banquets are held in residential neighborhoods, where everyone joins hands to contribute food or tables, or help with the organization of the nightly event.

In Saudi Arabia lavish banquets are held in the courtyards of the Grand Mosque of Mecca and the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina. In the United Arab Emirates, makeshift tables with a cornucopia of food are set up in the courtyards of mosques and Ramadan tents. They’re organized by charities and funded by benefactors.

5. ...filled with traditional foods

Tables are replete with sumptuous dishes tied to the holy month. Some dish names may be similar across countries, though recipes or ingredients might vary.

Dates are staple on every table, as the Prophet Mohammed broke his fast with dates and water. The practice has been followed by Muslims for centuries. Dates are rich in sugars, potassium, magnesium, and fiber—thus an ideal boost after a day of fasting.

Most Ramadan dishes are stew-like, higher in calories, and less dependent on spices—which might exacerbate thirst—all for the sake of keeping the body hydrated and filled throughout the long fast.

A selection of iftar dishes include thareed, an Emirati dish of bread cooked in broth with lamb and vegetables; molokhia, an Egyptian soup made of molokhia, a spinach-like green, usually served with rice and roasted chicken; and harira, a rich Moroccan soup whose ingredients include meat, tomatoes, vermicelli, chickpeas, and lentils.

Levantine-style side dishes are widely consumed, including eggplant-based moutabal and ful, made from fava beans and a garlicky-lemon oil.

Finishing off the meal, Ramadan sweets include chebakia, a Moroccan cookie made with honey and sesame; luqaimat, fried doughnut balls sweetened with honey or date molasses, with a sprinkle of sesame; rice pudding; qatayef, a pancake stuffed with cream or nuts, then fried and sweetened with honey or syrup; and masoub, Yemeni banana bread pudding.

Ahmed Hammad is staff member of National Geographic’s Arabic edition.