The site of America’s worst antisemitic attack wants to tell a story of hope

Years after the horrific mass shooting in 2018, Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue aims to rebuild with a new design to “balance the light with the darkness.”

Pittsburgh — They all remember the minutes, and the hours, when Tree of Life ceased to be the quiet aging synagogue on a hill.

Paula Garret, running late for services, was leaving home when her phone pinged with frantic “don’t go” messages because gunshots were heard at the corner of Shady and Wilkins avenues. Andrea Wedner and her 97-year-old mom, Rose Mallinger, were sitting on a wooden pew inside when a thunderous steely rattle shook the synagogue’s walls. Get down, Wedner said in a breath too late for the gunman rounding the corner. Carol Black scurried into a dusty closet as her brother Richard Gottfried was lost forever in the chaos. Dan Leger, a congregant struck by several bullets, thanked God for a good life as he bled in a stairwell.

Before noon that October day in 2018, the worst antisemitic attack in American history—at one of the oldest urban Jewish communities in the country—was over. Eleven people were murdered, and others grievously wounded, including police who fought and captured the shooter.

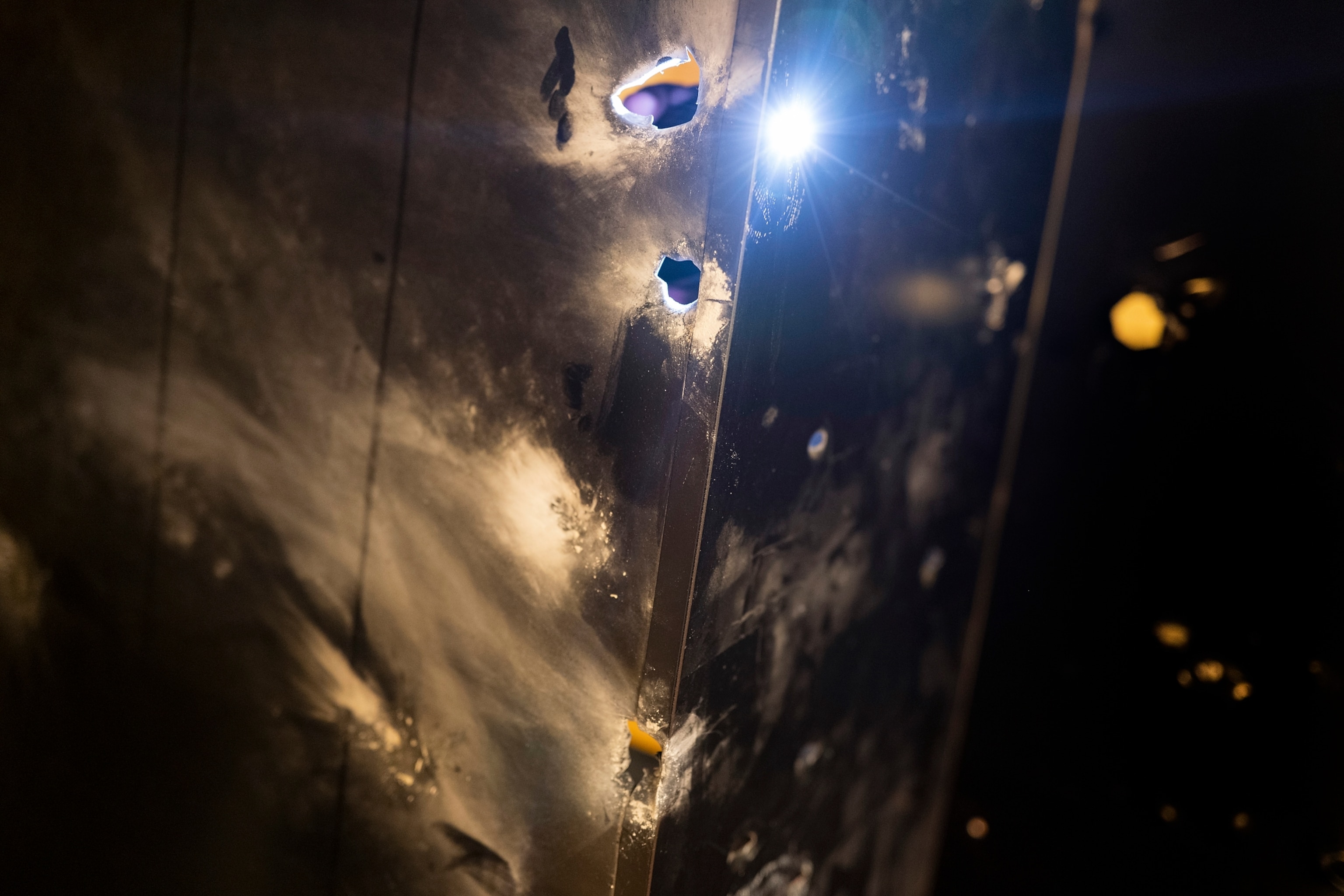

Prayer or any sense of comfort seems unimaginable in the ruined halls today. A top-floor children’s classroom is riddled with rounds from an AR-15 rifle. Bloody carpets have been stripped to cold concrete. There are still chalk markings wherever people died. V = victim. The milky letter is etched, again and again, above door frames.

Yet people in Pittsburgh, a city of 300,000, believe something good is possible in the desecrated temple that housed Tree of Life and neighboring Dor Hadash and New Light congregations. After discussions, disagreements, pulling apart and pulling together, they are salvaging the killing ground in a most American way: a new corporation—T of L Inc.—will recast its landscape and purpose.

Now, at a time when hate crimes against Jewish people have increased, T of L Inc. will exist to eliminate antisemitism, and Tree of Life will tell a story of redemption, not a massacre, and how a community forged peace from a terrible loss. Studio Libeskind, a New York architecture firm led by world-class architect Daniel Libeskind, has drawn the blueprints, in counsel with Pittsburgh architect Daniel Rothschild, for a groundbreaking this year.

“We’re inventing something new here,” says Jeffrey Myers, Tree of Life’s rabbi who dodged bullets that day. That means asking sensitive questions, he adds. “What’s the source of all this violence? Where does it come from? …We are, unfortunately, uniquely positioned to take that on.”

Tree of Life leaders and its civic neighbors began talking weeks after burying their dead. They decided that something must be done.

Restoring what was lost

Former synagogue president Paula Garret joined hundreds of volunteers who sorted through daily mundanities in the aftermath, including opening thousands of letters and emails from as far away as Mumbai.

“We knew this as a horrible attack, and, yes, the worst antisemitic attack on U.S. soil,” says Garret. “But the response was broader than that. From Jews, non-Jews, Muslims, Christians, survivors of other shootings. We kept thinking: what can we do with that?”

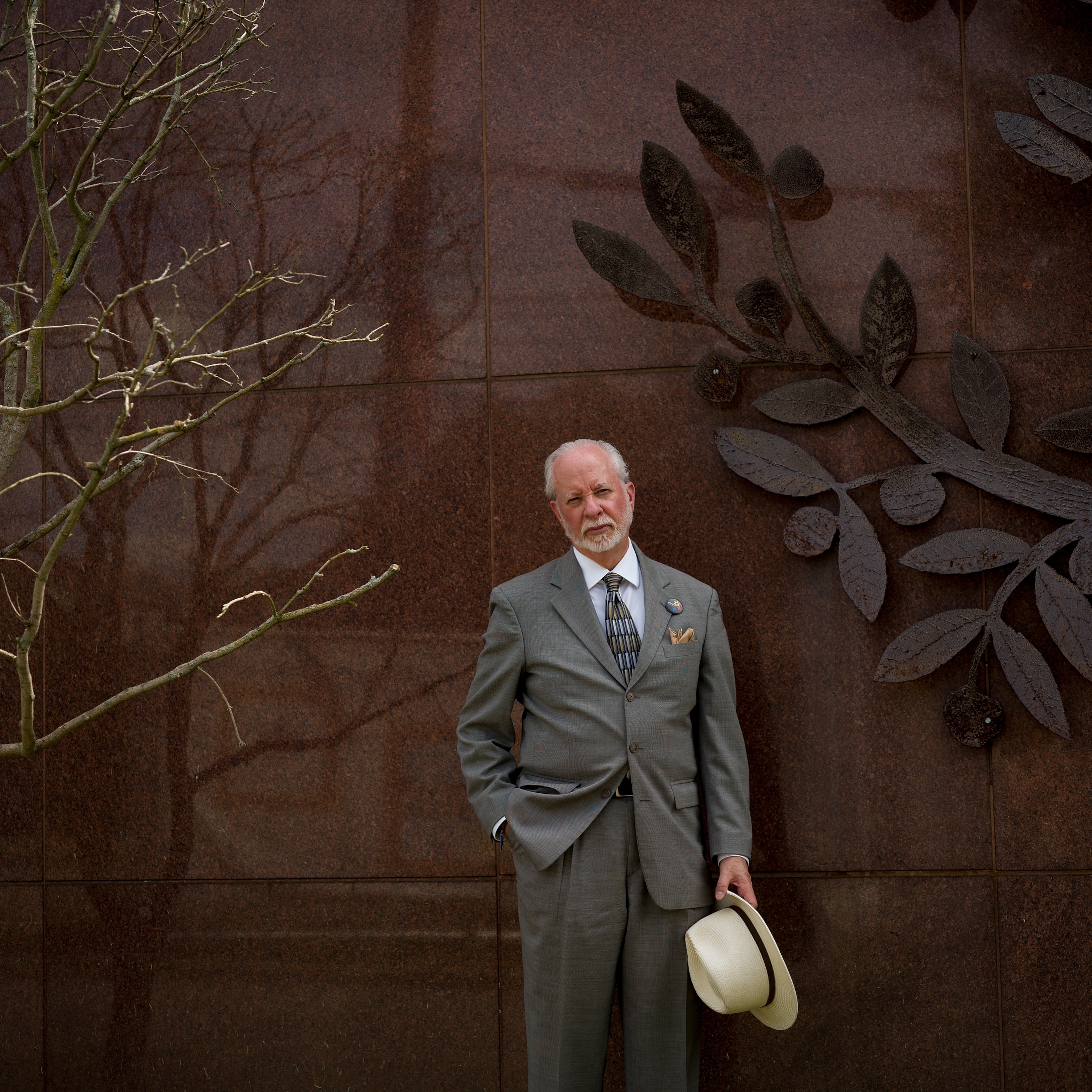

Less than a month after the shooting, Rothschild, who decades earlier had designed a modest extension to the synagogue, received a phone call asking if he would take a tour of battered temple. He joined several past presidents on a walk through the entire building until they entered the bullet-ridden chapel. “We stood in silence,” Rothschild says. “They asked: ‘So what do you think we should do?’” Rothschild was blunt: “I don’t know, but right now, this has nothing to do with architecture.”

Rothschild had long helped communities stunned by disasters or deprivation. His firm, Rothschild Doyno Collaborative, had worked in earthquake-shattered Haiti and in tough areas of Newark, N.J. He told Tree of Life leaders to proceed with caution.

“Every person is still trying to process this,” Rothschild advised. “Let’s help relieve people of the thoughts rattling around in their heads.” He volunteered to hold “listening sessions” to explore the loss of a community pillar.

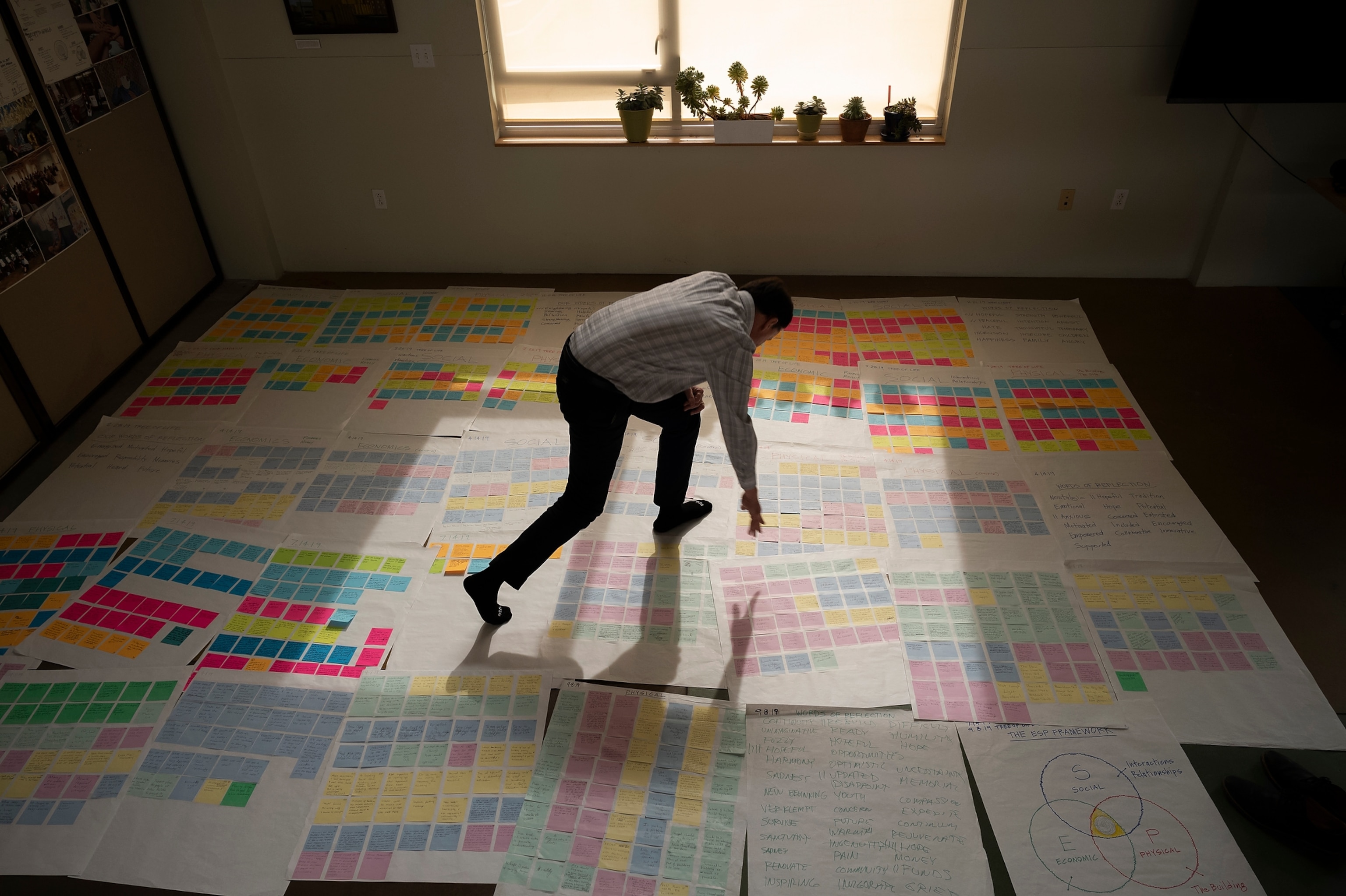

He met with about 160 people in small groups over the next year to share memories. Some missed their home for Shabbat. Others recounted weddings and bar mitzvahs. Rothschild asked them to write a sentence or a word on Post-it Notes. Did they have hope?

By the end of 2019, Rothschild had collected about 2,000 statements with words that captured the lingering sentiments: “sadness” and “grief” abounded. But feelings of being “optimistic,” “hopeful,” and “energized” were rising in number. Rothschild created a data bubble, reflecting the thoughts about 10/27, the date often used as a verbal shorthand for the attack. The good was outweighing the bad.

“I don’t want to sugarcoat it,” he says. “There was definitely pain and anger and negative thoughts, but something had happened by people talking and hearing each other. They began thinking about what comes next…they started to heal.”

Remnants of grief

Deadly shootings have bloodied acres of America, and communities often stagger for years to reclaim places of slaughter.

Mother Emmanuel AME church in South Carolina held services four days after a gunman shot dead nine people at prayer. Other communities have found themselves unable to return. Parkland, Florida plans to demolish the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School building where 17 people died in the 2018 mass shooting. The Pulse nightclub in Florida, where 49 people were shot to death in 2016, remains closed. Sandy Hook Elementary in Connecticut, where 26 people were gunned down in 2012, was leveled, and a new school built.

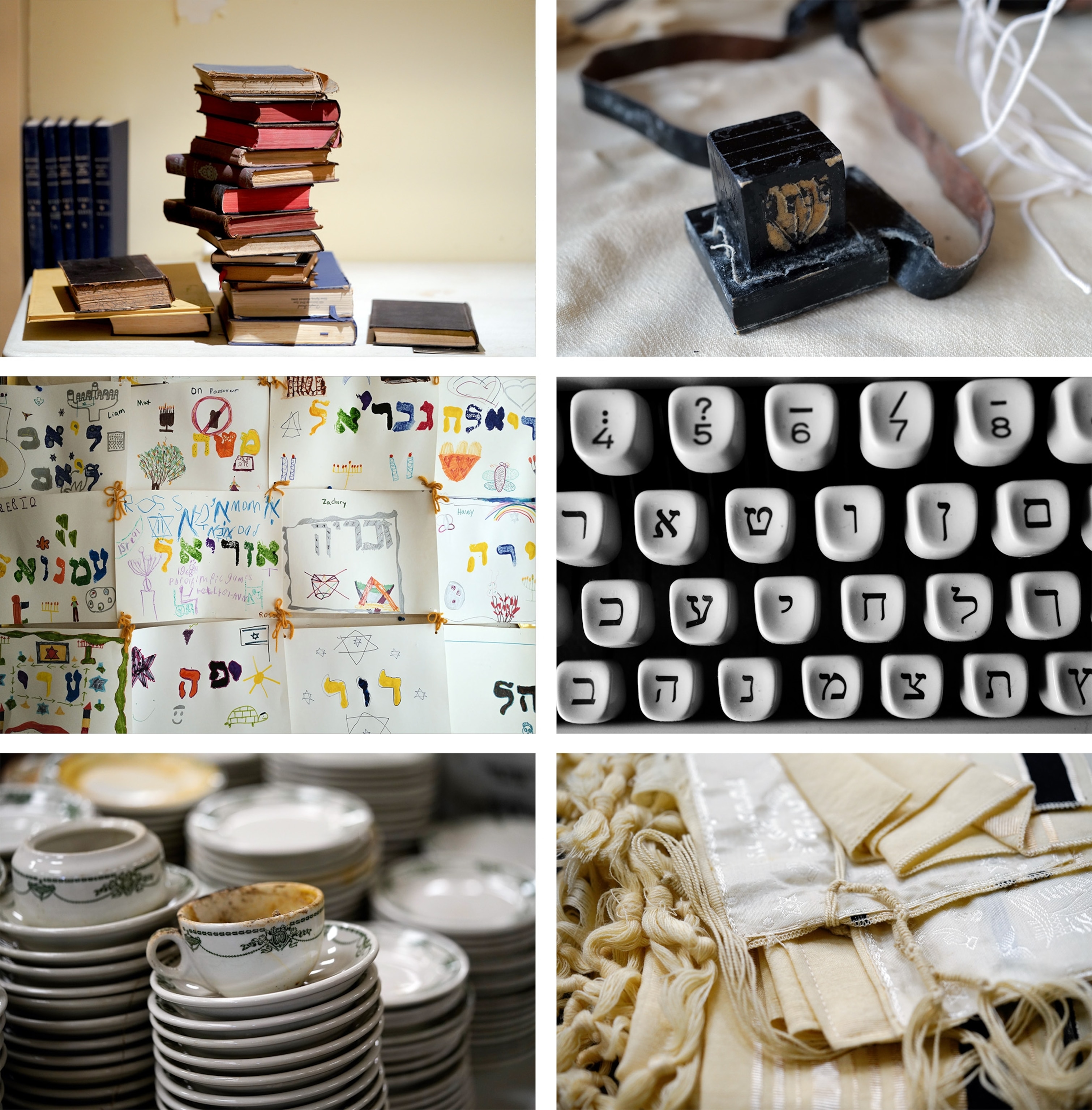

The Jewish community of Tree of Life dates from the 1860s but the synagogue’s heyday had long passed by 2018. Its rooftop was beginning to rust and stained-glass windows sagged. The sanctuary could seat 1,200 people but all three congregations drew only a few hundred for services and that only on high holy days. Dor Hadash and New Light settled into other synagogues soon after the attack, with no plans to return.

If Tree of Life was to rebuild, who would come? Should a revision reflect grief?

The leadership put out an open call for architects to help.

Seventy-six-year-old Libeskind—who landed in New York as a 10-year-old immigrant, leaving Poland for Israel then America—has documented trauma and history in magnificent ways in his career. He designed the Jewish Museum of Berlin to reflect the scars of the Holocaust and political times that spiraled into terror. His own family lost 85 relatives in Nazi-occupied Poland. Libeskind also was the master planner of New York’s 9/11 site; he listened to sufferers as well the politically connected to wrest beauty from a colossal graveyard.

As he considered the scenes in western Pennsylvania, Libeskind felt a bond. Tree of Life was attacked in part because the Dor Hadash congregation supported HIAS, a nonprofit group that helps refugees. HIAS, founded as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, had settled Libeskinds’ family decades earlier. “The attack that was planned—and it was very well planned—was not just antisemitic. It was anti-American,” Libeskind says. “It’s against the founding principles of America.”

The 45,000-square-foot complex had to remain authentic, Libeskind says. “In Berlin, it was about reflecting the abyss, about the genocide that was from the city. In Pittsburgh, it is an event, a terrorist attack on Jews and an antisemitic attack to kill Jews on Shabbat. It’s not to be museum. It’s a place for prayer, for bar mitzvahs, for everyday life.

“It’s about hope,” Libeskind says. “But it has to reflect all that happened, not just the attack. There was a community that quickly came together. Christians, Muslims, it was all about solidarity. It wasn’t just a response of Jews and about Jews…This effort to rebuild is about the power of people to create communities across boundaries.”

“People here might think this (project) is about Pittsburgh,” adds Studio Libeskind partner, Carla Swickerath, “but it resonates far beyond that.”

Libeskind and Swickerath returned, time and again, to meet congregants. Libeskind has a reverence for memory in his work. This site, he said, “could not suffer amnesia.” Within a year, they unveiled a design to “balance the light with the darkness.”

Towering stained glass, in the chapel and the sanctuary, will remain. A huge skylight will cut through the length of the roof. The synagogue will be halved, with spaces carved out for study, films, even yoga. The Pittsburgh Holocaust Center will eventually move in; nearby Chatham University will develop programming. There will be a memorial for the 11 dead. “This will all speak to resilience. Of people who continue to believe. Who have not lost hope,” Libeskind says. “In many ways, Pittsburgh is a model American city, a place where people learned and continue to learn, how to live together.”

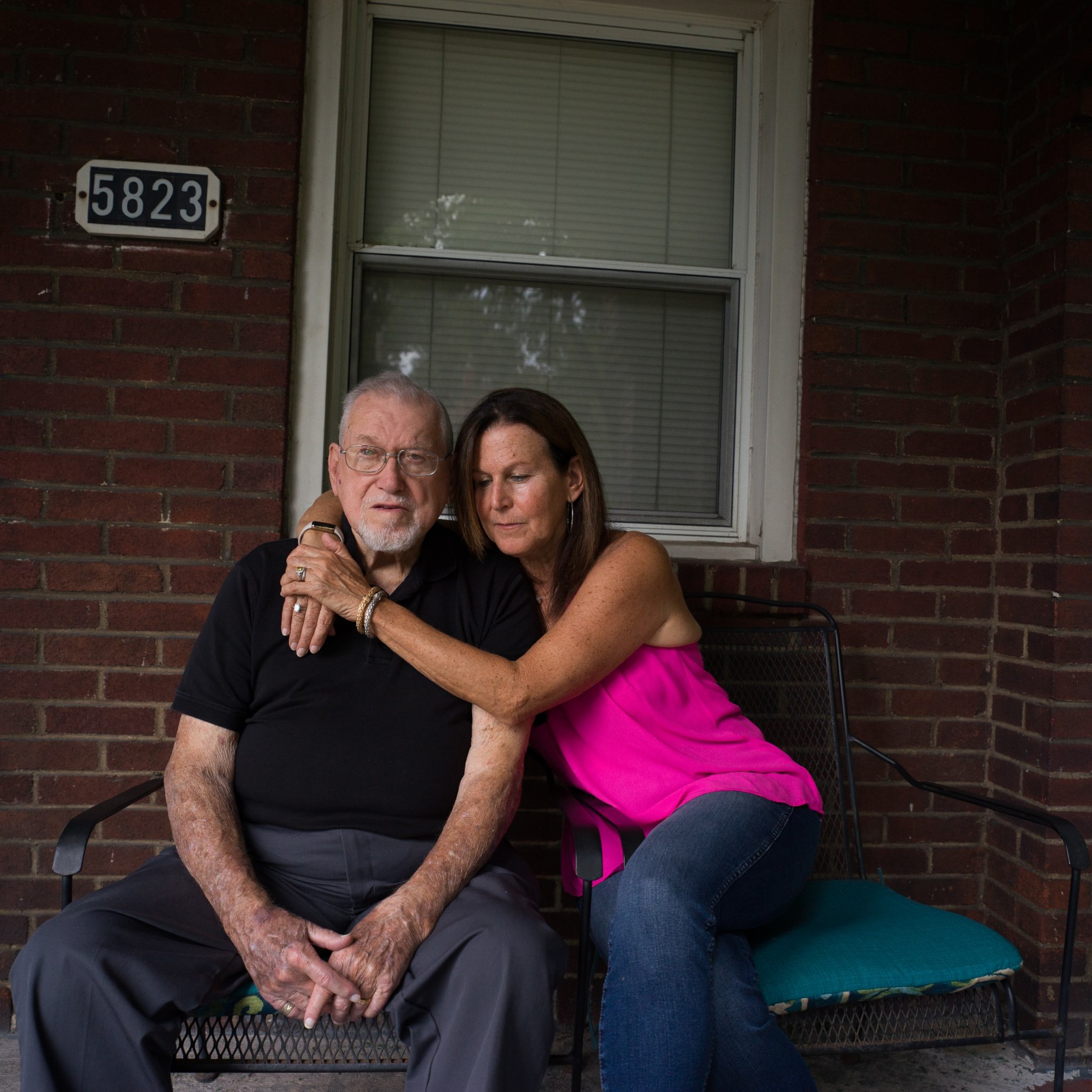

Portraits of Loss & Resilience

Coming to terms with hate

What binds those who experienced the attack in 2018 is that they are so grateful for life—even if they differ on ways to remember the dead.

Wedner’s parents were synagogue stalwarts and generations prayed there. She says she knew, as bullets crackled, that her mother, Rose Mallinger, was gone. Today Wedner bears deep scars on her arm and hand that limit her dexterity. But she speaks with certainty about what her mother would want. That her daughter sees much to live for and that Tree of Life rebounds.

“You can’t go back and change what happened,” says Wedner, 66, adding that the new building will “be a memorial to mom but also to a family tradition. Before it was just a synagogue. Now it’s going to be much more.”

Black, a member of New Light, has no intention of praying, ever, at Tree of Life. She crossed its threshold once after her brother Richard Gottfried was slain, and “I am never doing it again,” she says. “I’ve made friends, very good friends, from the other congregations. But we don’t agree on this particular issue…I mean, there are always disagreements among family. You don’t stop loving each other because of a disagreement.”

The physical building was never that important, says Leger, the member of Dor Hadash who bled in a stairwell then endured multiple surgeries over four years from the gunshot wounds. The rebuild seems immaterial, no matter how beautiful. “Can I find peace and solace again in my life? Of course, I can,” Leger says. “Listen, life is hard. Bad things happen—and they have always happened. It’s what you do next that matters. Hate back? That doesn’t give anyone peace.”

“If the building is just a memorial that reminds everyone of what happened, it is a waste of money,” says Leger, 74. “If it achieves the goal of having people think about how to stop antisemitism—or even if it stops one act of hate—then it is good.”

National Geographic Photography Fellow Lynn Johnson is a regular contributor to National Geographic magazine who has photographed the global human condition for the past 35 years. She previously covered the Tree of Life tragedy for the magazine in "This American Jewish community is ‘the heartbeat of Squirrel Hill." Follow her on Instagram.