Thousands of oil rigs are nearing the end of their life—what will happen to them?

Massive, offshore rigs the size of skyscrapers remain at sea around the world. Here's why these environmentalists say some should be left alone.

Beneath the surface of oceans worldwide, around 12,000 offshore oil rigs have been built to tap into the deep reserves of oil hidden beneath the sea floor. But over the next decade, hundreds to thousands of them will reach the end of their lifespan as wells run dry or become less profitable.

How to safely remove these massive structures from the ocean, a process called decommissioning, is complicated.

Dismantling these towering steel rigs, some of which reach the height of skyscrapers, is a multi-million-dollar endeavor involving plugging wells, removing equipment, and rehabilitating the seafloor. However, some rigs have become a habitat for marine life in the decades since they’ve been built, functioning like artificial coral reefs.

This marine life has created a complicated debate: Should the companies who built the rigs dismantle them entirely, potentially disrupting thriving marine ecosystems? Or should these structures be left in place, letting energy companies leave enormous pieces of infrastructure in the sea?

What happens when a rig closes?

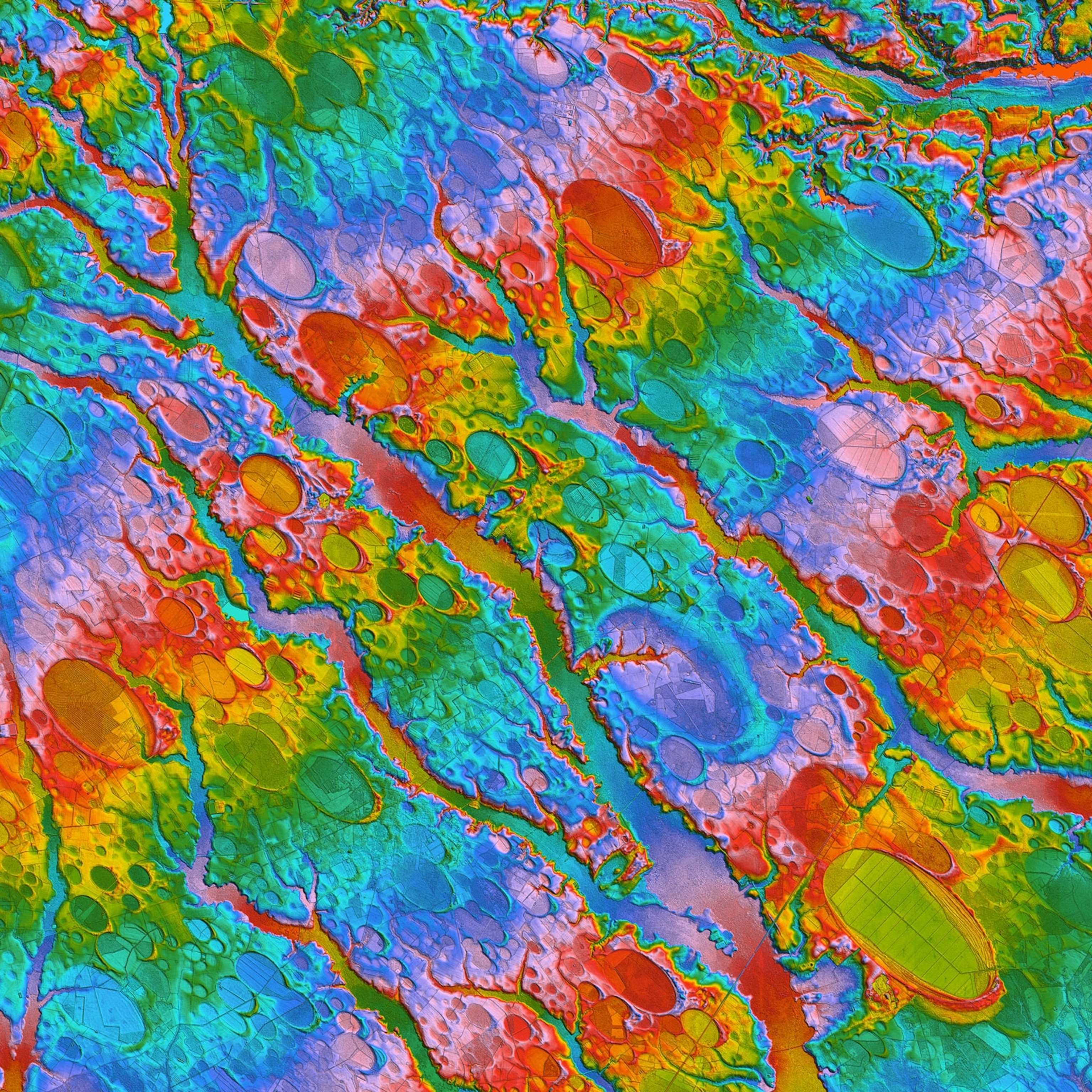

To find pockets of oil and gas under the sea floor, energy companies use loud air guns to create seismic maps. Once a large deposit is found, rigs (also called platforms) more than two miles deep are anchored to the seafloor, though some float.

These platforms are immense. The Bullwinkle platform in the Gulf of Mexico is taller than the Empire State building and nearly twice the size of the Eiffel Tower. Platforms contain dorms, withstand hurricanes, and in the Gulf alone offshore rigs have produced more than 23 billion barrels of oil.

When wells begin running dry, cement plugs are commonly used to seal off a site, limit air and water pollution, and allow the ecosystem to return to its original state. Yet, a paper published in Nature Energy in 2023, estimated that in just the waters off the coasts of Texas, Louisiana, and Alabama, 14,000 inactive wells have not been plugged. Doing so, that same study estimates, would cost over $30 billion.

And even when wells are sealed shut, there’s the complicated question of what to do with the hundreds of feet of infrastructure that anchored them in place.

Steel materials might be recycled, transported to landfills, or—in rare cases, buried in the deep-sea. Partial decommissioning, where only the upper section of the rig is taken down to a depth of approximately 85 feet, leaves the lower portion of the rig for marine life. Under the U.S. Department of Interior’s Rigs-to-Reef program, almost 600 wells have been converted to reefs since the 1980s.

But not every rig is suited to being repurposed as a reef.

Dianne McLean, a senior researcher at the Australian Institute of Marine Science says rigs should be assessed case by case. Differences in rig design, nearby currents, depths, and marine life make a one-size-fits-all approach impractical.

Why leave an oil rig in the ocean?

Invertebrates like mussels, corals, sea anemones, and starfish sometimes cling to pilings—the massive underwater foundation mooring a rig in place. These then attract crustaceans and larger fish species.

When a rig is left in the ocean to become a reef, fish populations around rigs can flourish, in part because of safety zones enforced by many countries that prohibit vessels from coming within around 1,600 feet of the rigs. But it’s unclear whether the fish are simply aggregating at a rig or if populations are growing overall.

A 2023 study published in Trends in Ecology and Evolution found that there wasn’t yet enough scientific evidence to determine if an unused old rig caused more environmental harm or benefit. And a more recent survey of 39 scientists found that most of the participants thought rigs were bad for the environment when left in place, except when those rigs created a habitat for valuable species.

Ann Bull, a marine scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, has spent decades exploring and studying oil rig pilings, the large platforms anchoring a rig in place.

“I was just astounded by the way that the fish were using the expanded steel,” she recalls from one of her first dives in the Gulf of Mexico.

When a rig becomes home to an endangered species, the question of how to decommission it becomes even murkier.

An international agreement signed in 1998 dictated that decommissioned oil rigs in the North Sea should be entirely removed, regardless of marine life. But in 2006, researchers found that a thriving population of coral (Lophelia pertusa) was present on 13 out of 14 investigated oil and gas platforms. The North Sea has faced dramatic biodiversity loss in the past decades, and the endangered species is one of the only reef-building corals in the U.K.

“When you take them out, you aren’t returning the water to some wonderful ecological condition,” says David M. Paterson, an ecologist at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. “You’re actually leaving it worse, because you’re taking out one of the only biodiversity hotspots around.”

A more crowded ocean

“This isn't a yesterday problem that we’re solving today,” says Samantha Murray, an attorney and Ocean Law and Policy Professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “We’re still creating this problem for tomorrow by leasing lands for offshore oil and gas, and in that case, we’re still going to be talking about how to handle decommissioning 60 years from now.”

The U.S. Department of Interior is planning to sell more Gulf of Mexico offshore drilling leases between now and 2029. And in just the past 20 years, thousands of offshore platforms that generate electricity from wind and waves have been built, with many more planned.

They too will need to one day be decommissioned, and Paterson says they can learn from the oil and gas industry.

“What will be colonizing these other structures when they’re put into the ocean? What’s the influence of them on connectivity in a region? All those sorts of things I think are important learnings to inform other offshore renewable energy,” says Paterson.