Mexico is treating corn from the U.S. as a threat. Here's why.

Corn originated in Mexico, but fears that genetically modified seeds could contaminate these ancient varieties have led to bans on certain U.S. imports.

The corn eaten around the world today originated in Mexico nearly 10,000 years ago. From the ancient rituals of the Mayans and Aztecs, to the tortillas, tamales, esquites, and just about every other staple dish served throughout the country today, corn is the centerpiece of culture, cuisine, and identity.

To protect this legacy, Mexico is fighting to phase out genetically modified (GM) U.S.-grown corn this year, following a 2020 decree by Mexican President López Obrador that sparked tension between the two neighboring countries.

The Mexican government says this will protect its citizens’ health and the country’s native corn varieties.

Yet the announcement provoked strong objections from the U.S., whose largest annual customer for GM corn is often Mexico—between 2018 and 2020, Mexico bought nearly 30 percent of all U.S. corn exports. The dispute has escalated to formal negotiations under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), with the U.S. claiming that the GM ban is in violation of the countries’ trade agreement and that Mexico has not provided scientific evidence to support its claim.

Mexico, however, insists that GM corn threatens human health, and that modified seeds threaten Mexico’s agricultural traditions and cultural identity.

“Without corn, there is no country”

There is a Spanish idiom—“sin maíz no hay país”; meaning that “without corn, there is no country”— an ode to the legacy and treasure of this agricultural asset.

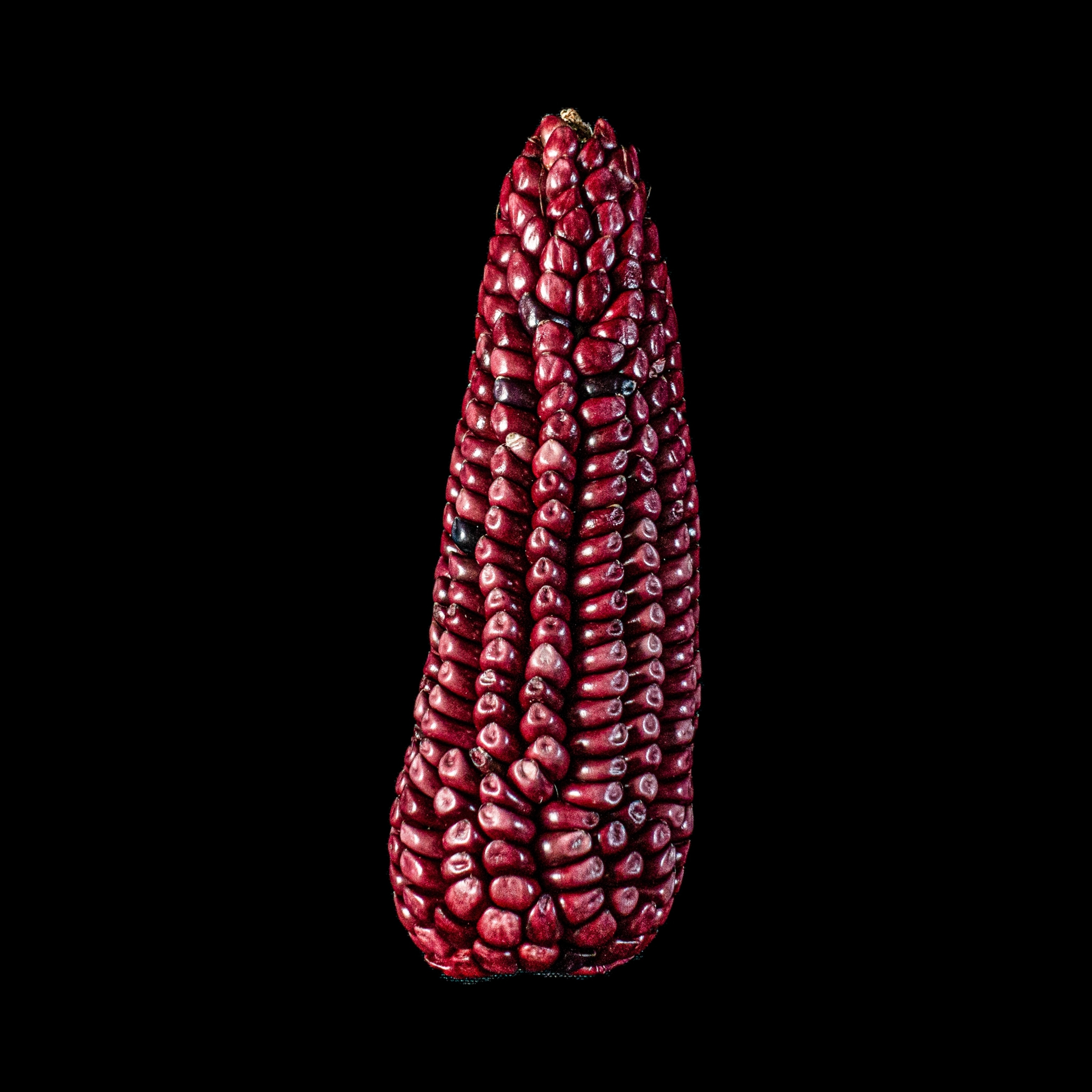

Mexico is home to the most genetically diverse repository of corn in the world, hosting more than 59 unique varieties.

What began as a wild grass called teosinte nearly 10,000 years ago in present-day Mexico has evolved through millennia of domestication and selective breeding to yield the corn that we know today. The native varieties are well-adapted to the local environment—some have evolved to require less water, and to be more pest resistant, two coveted traits in the face of a changing climate.

Mexico is concerned that GM corn poses the risk of genetic contamination—genes from U.S. corn have a history of crossing the border and entering Mexican varieties. Pollen from GM crops can travel considerable distances and cross-pollinate with the native varieties, potentially altering their genetic makeup and, in some cases, making them less suited to the specific conditions they were bred for.

In the U.S., most corn is grown with seed produced by large corporations, which create just a handful of genetically identical corn varieties grown at mass scale. In Mexico, however, seeds come from seed-sharing milpas, which facilitates more diversity and allows farmers to grow corn that ranges widely in color and size.

The mix of genetics housed in different native corn varieties can help corn adapt to challenging environments—a gene that confers drought tolerance, for example, could be cross bred into a variety that struggles without water.

“Traditional varieties maintain a substantial amount of genetic diversity,” says Jeffrey Ross-Ibarra, an ecologist at the University of California, Davis. “There’s probably more variety in Mexico than all of the U.S.”

Why the U.S. is fighting back

While Mexico receives a hefty portion of U.S. corn, most of that corn is dedicated to animal feed or industrial use, which is not impacted by the ban. The corn prevalent in Mexican diet and cuisine is white corn, which makes up just one percent of American corn production.

In 2023, Mexico officially banned GM corn for human consumption, putting the proposed ban into immediate effect. That same year, Mexico also made its largest corn purchase from the U.S., 15.3 million metric tons.

Yet U.S. corn producers and trade officials are concerned the decision to ban GM corn for human consumption could open the door to further restrictions.

“Right now, it may not have a big economic impact because what Mexico is using to produce flour, cornmeal, and tortillas is a very small percentage of their overall imports; but that does not mean the U.S. is not concerned with this being the tip of the iceberg,” says Kenneth Smith Ramos, former Mexican chief negotiator for the USMCA.

Mexico first imported modified U.S. corn in 1994, when NAFTA (the predecessor to USMCA) mandated tariff-free access to low-priced American corn. Mexico is not legally obligated to purchase U.S.-grown corn, though its low cost makes it a popular choice.

“Mexican corn farmers just can't compete with American farmers on production efficiency,” says Evan Rocheford, co-founder and CEO of NutraMaize, an AgBioScience company commercializing more nutritious varieties of non-GMO orange corn.

There’s no evidence that genetically modified foods harm human health, according to the Food and Drug Administration. And the U.S. has accused Mexico of violating the USMCA, citing a lack of scientific evidence that GM corn is harmful to health and the environment. Mexican officials claim that the U.S. has been unwilling to collaborate on research studying the health implications of GM corn.

Mexico plans to ban glyphosate, an herbicide that may harm health. Concerns about the chemical were sparked by a controversial 2017 report that may have overstated the risk of glyphosate exposure. A subsequent study published in 2021 found the chemical was present in children who hadn’t had any direct contact with it, though no major health problems were directly tied to the chemical. Mexican government officials remain concerned that GM farms require the use of glyphosate in their farming practices.

Preserving corn’s genetic diversity

Though Ross-Ibarra is concerned about conserving native corn, he doesn’t think banning GM corn will help preserve these varieties, and points to a decline in small-scale farms as the greater threat to native corn.

“If traditional farmers abandon subsistence farming, we’re potentially losing diversity whether that crop is GM or traditionally bred, so economic policy has a much bigger impact on risk of maize diversity than an adoption of GM corn,” he says.

Since Mexico began importing U.S. corn, small-scale milpa farms have been declining.

“Evolution at scale continues with maize in Mexico through millions of farmers, which only happens in a very limited way in the U.S. because the seeds are held by a few corporations,” says Mauricio Bellon, a research professor focusing on sustainable agricultural and food systems of smallholder farmers in the developing world at the Swette Center for Sustainable Foods Systems of Arizona State University.

And while threatened species are often stored in gene banks, Bellon says the relationship of a farmer and their crop play a crucial conservation role.

“The banks are like a photo, a snapshot of whatever was there when the seed was collected 10, 20, 30 years ago,” says Bellon. “Whereas what you see in the farmer’s field…continues on. If we lose them, we are losing options.”