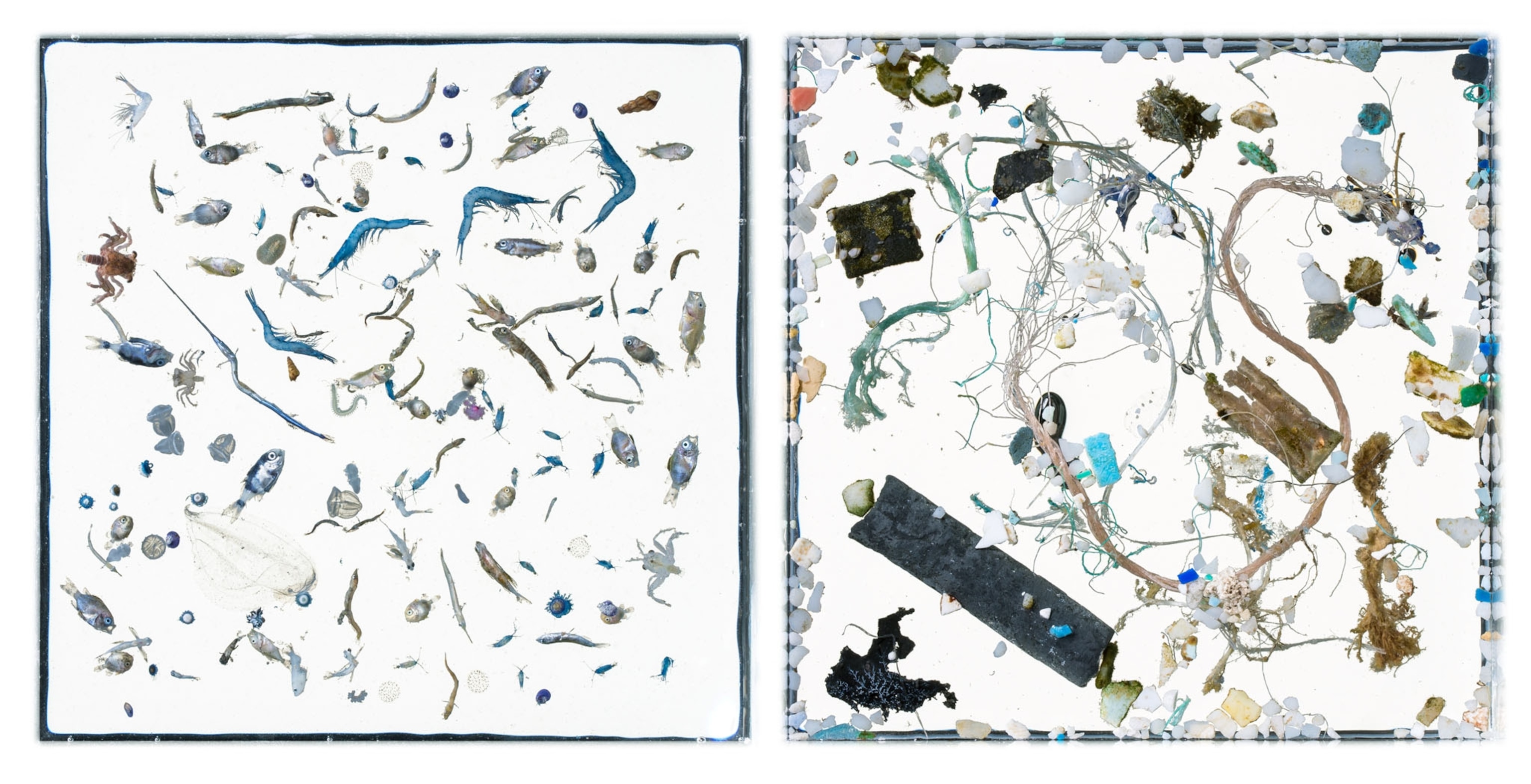

Striking photos reveal plastic and plankton side-by-side

Hidden just beneath the surface of the ocean is a world where tiny ocean creatures must navigate a dense world of plastic soup.

Converging currents at the surface of the ocean create some of the best places to find life. It's there that tiny plankton hang out—and where plankton float, hungry fish follow.

It's also there that researchers are finding a new, and now ubiquitous, ocean resident—plastic.

“To me it's a little shocking how much is in relatively small samples,” says photographer and National Geographic Explorer David Liittschwager. Last July, Liittschwager accompanied scientists sampling waters off the coasts of Hawaii, where currents converge to form slicks full of plankton. Using nets, they scooped 400 cubic meters of surface water into simple five gallon buckets and hauled it back to a lab on Hawaii's Big Island.

In addition to photographing water samples from Hawaii, Liittschwager also studied waters in a lab in Plymouth England. That surface water was collected nearby from buckets towed behind large ships.

Liittschwager spread the water onto trays to photograph the contents up-close. His photos reveal a world in which the movements of plankton and plastic are intertwined. Small larval fish float alongside colorful bits of plastic and fishing twine. Some images are so dense it's difficult to discern what's alive and what isn't.

While the images themselves look like colorful pieces of abstract ocean art, these samples reveal an insidious and growing ocean threat. Microplastic, any piece of plastic that measures smaller than five millimeters, is found in all the world's oceans. It flows through inland rivers, and it reaches the deepest trenches in the ocean. Microplastic is the result of plastic trash being broken down into seemingly invisible plastic particles by wear and UV light.

Scientists are now trying to figure out how microplastics might be harming people and marine life. In 2017, one study revealed anchovies mistake plastic for food, possibly lured in by the scent of algae coating the garbage. As these small fish are consumed by larger fish higher up the food chain, scientists worry they might end up on our plate. A study published last October found microplastic is already present in 90 percent of table salt.

“Plastic is an amazing material,” says Liittschwager. “But the idea of making something single-use is preposterous.”

He's been moved by images of plastic obscuring natural wonders for the past two decades. In 1994, it was a littered beach in Hawaii, where some shores are on the receiving end of trash from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Ten years later, he was on a remote Hawaiian island with scientists trying to figure out why albatross chicks were dying early. A necropsy of their stomach contents revealed bottle caps and other bits of plastic.

As Liittschwager describes it, his mission is simply to document what's real.

“I' d like people to see what's really there,” he says.

National Geographic is committed to reducing plastics pollution. Learn more about our non-profit activities at natgeo.org/plastics. This story is part of Planet or Plastic?—our multiyear effort to raise awareness about the global plastic waste crisis. Learn what you can do to reduce your own single-use plastics, and take your pledge.