Protecting land and animals will mitigate future pandemics, report says

The same forces driving extinction, habitat loss, and climate change will also lead to future pandemics, say an international group of scientists.

Absent major policy changes and billions of dollars invested in protecting land and wildlife, the world may see another major pandemic like COVID-19, an international group of scientists warned today

Conserving biodiversity can preserve human lives, according to their new report, which reviews the latest research on how the decline of habitat and wildlife leaves humans exposed to new, emerging diseases.

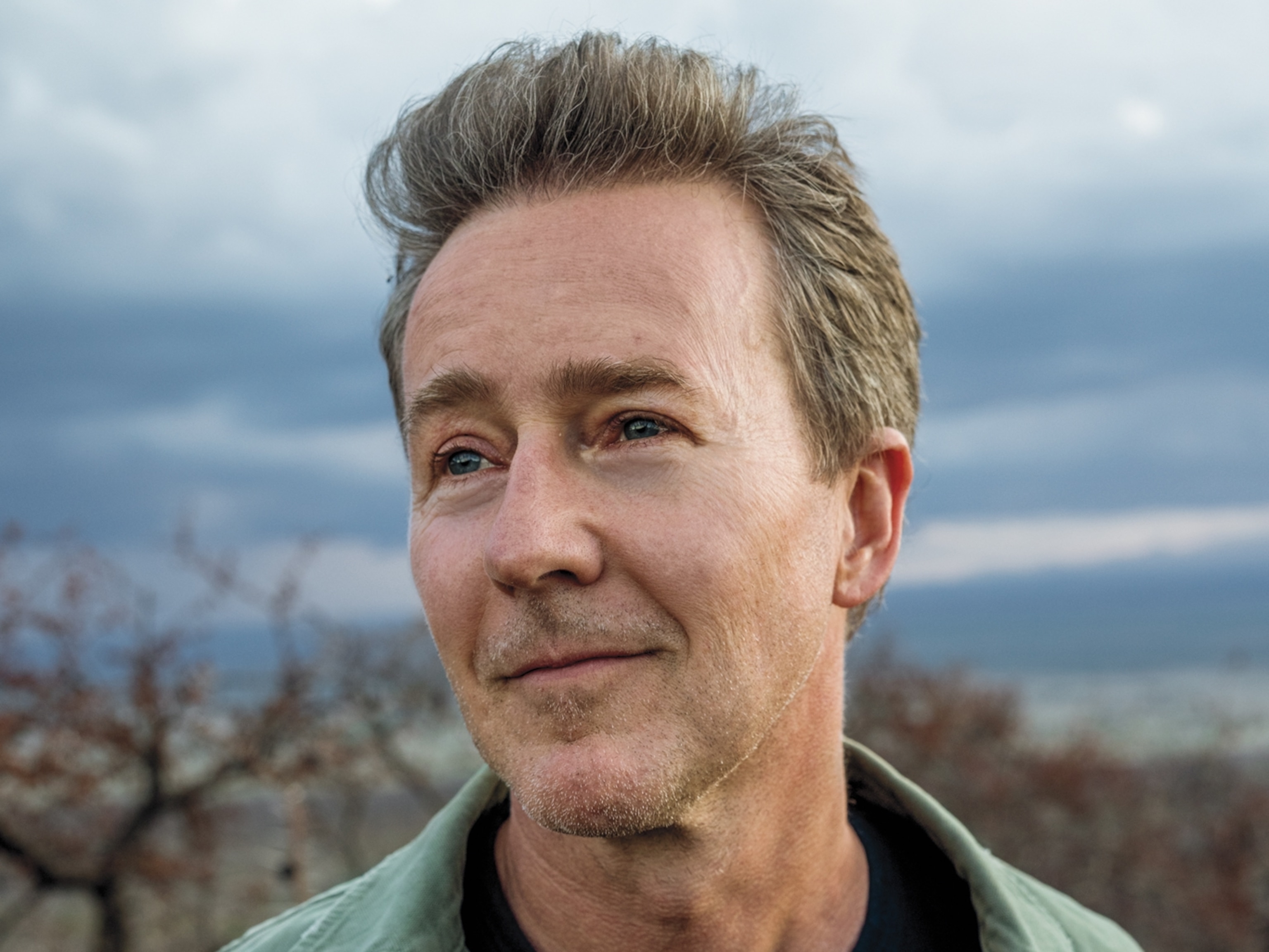

“The science is not in dispute at all about this. Deforestation is a prime driver of pandemics,” says Lee Hannah, a climate scientist for Conservation International who specializes in the effects of forest loss. Hannah peer-reviewed the report, which was compiled at a late July virtual workshop by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), a group of scientists from academia, governments, and nonprofits.

“Without preventative strategies,” the report says, “Pandemics will emerge more often, spread more rapidly, kill more people, and affect the global economy with more devastating impact than ever before.”

Habitat destruction and disease—what’s the link?

The report’s recommendations take what it describes as a preventative approach to stemming the spread of diseases that commonly emerge from animals.

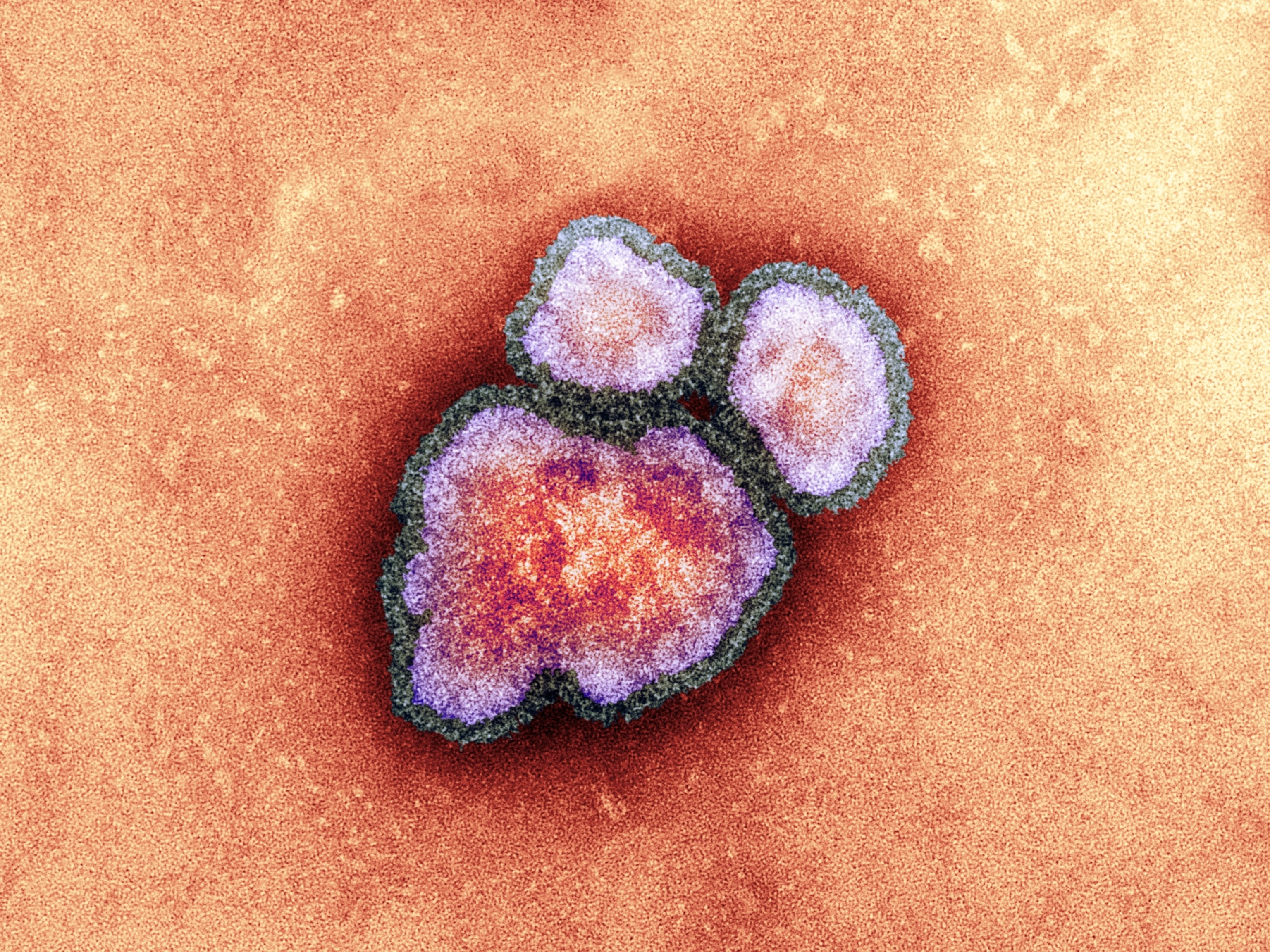

So-called zoonotic diseases—which include COVID-19, HIV, and influenza, and the Ebola, Zika, and Nipah viruses—emerge from microbes living in wildlife that can infect humans. Bats, birds, primates, and rodents are common transmission sources.

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has been traced to a wet market in Wuhan, China that may have been the source of the original outbreak of COVID-19 in humans.

Scientists estimate that there are 1.7 million undiscovered viruses lurking in mammals and birds, half of which may have the ability to infect people. It’s no coincidence, say the report’s authors, that pandemics are growing in number as human activities place more stress on the environment and bring people into increasingly closer contact with wildlife.

As recently as November 2019, scientists were sounding the alarm that increasing deforestation was creating more favorable conditions for disease outbreaks. While habitat loss writ large presents a threat, Hannah calls specific attention to forests, which have a high density of biodiversity and therefore present more opportunities for disease carriers. He notes as an example deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, where forests are often cut to make way for cattle to graze. Cattle can also act as intermediaries between infected wildlife and people who work closely with livestock.

Destroying wildlife habitat will also drive animals into new territories, the report says, forcing animals, including bats and birds, to find homes in urban environments in greater numbers.

A steep cost to solutions

“I think the really important thing is understanding the scale at which we have to operate here,” says Hannah. “This isn’t about pumping things up a notch; this is about taking things to a level they’ve never been taken before.”

The report proposes launching an international counsel to oversee pandemic prevention, financially incentivizing biodiversity conservation, and investing in research and education. These institutional changes, they hope, would curtail the reach of industries such as palm oil production, logging, and ranching.

They would also help identify emerging hotspots and provide more robust health care for the people at greatest risk of exposure.

To fully roll out a strategy that lowers our risk to future pandemics would cost between $40 and $58 billion every year, estimate the study’s authors. But, they add, it would offset economic losses from pandemics that amount to trillions. One study published earlier this month said COVID-19 has cost the U.S. alone $16 trillion so far.

Thirty countries have pledged to support the Campaign for Nature, a global goal to protect 30 percent of the world’s land and seas by 2030. But, says the campaign’s director Brian O’Donnell, there are several steps that need to be taken to make these pledges reality. (The Campaign for Nature is supported by the National Geographic Society.)

Next May, countries will meet for the U.N.’s Convention on Biological Diversity, where they will have the opportunity to develop strategies to contribute to this global conservation target.

“We need all of the countries to agree,” says National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence Enric Sala of supporting ambitious conservation targets. “Especially those that harbor the largest wildernesses left on earth, which are not only the largest reservoirs of biodiversity, but also the greatest nature-based solutions to help mitigate climate change.”

O’Donnell is concerned about the delay caused by COVID-19 in moving these plans forward, saying even a year’s delay is a risk.

“We have yet to see major new tangible financial commitments for nature conservation even as governments are spending large sums on stimulus,” he added via email.

In addition to COVID-19, O’Donnell says roadblocks include lack of funding and support from countries where major deforestation is occurring, such as Brazil.

He says he hopes the global pandemic will be a “major wake-up call.”

“A few are hearing the alarm” he says. But, he adds, “Too many are sleepwalking.”

If not for appreciation of the natural world and endangered wildlife, Hannah hopes this new report will help stakeholders see that human health is a compelling reason to conserve nature.

“There’s a selfish reason to do this, which is protecting ourselves,” says Hannah.