2024 was the hottest year ever—but it might be the coldest year of the rest of your life

Earth continues to break temperature records, but if it doesn't feel that way, you might be experiencing this subtle mind trick.

2024 was the hottest year on record, according to new data published by the Copernicus Climate Change Service. It was also the first year the planet surpassed the 1.5 degrees Celsius global warming target set forth in the Paris Climate Accord.

But years from now, you’re unlikely to remember 2024 as an especially hot year, because it will also be one of the coolest years of the rest of your life.

As humanity keeps burning fossil fuels and heating up the Earth, your future self will look back on the present as a time of calmer weather, snowier winters, and milder temperatures. To children born today, the hotter, stormier climate conditions of the future will feel normal.

This is due to a mind trick known as shifting baseline syndrome, which causes people to grow accustomed to whatever environmental conditions they’re currently experiencing. The phenomenon can lead to a gradual erosion of society’s environmental standards, whether those standards concern acceptable levels of air pollution or the number of fish in the sea. When it comes to climate change, shifting baseline syndrome may be causing society to normalize progressively hotter temperatures—and a host of other planetary impacts.

Some experts think that is a serious problem.

“Solving climate change requires significant changes in individual and collective behavior,” says Masashi Soga, an applied ecologist at the University of Tokyo. “Shifting baseline syndrome can act as a powerful barrier by reducing social recognition of the problem.”

Record breaking heat

Two years ago, climate scientists were talking about a dramatic new temperature record. 2023 was not only the warmest year in nearly 175 years of bookkeeping, but it was also roughly 0.15 degrees Celsius warmer than 2016, the previous hottest year on record.

In planetary terms, this is considered a major jump.

“The last two years have been kind of supercharged,” says Gavin Schmidt, the director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, which assembles the agency’s global temperature record from thousands of weather stations, ocean buoys, and ship-based observatories. While Schmidt says temperatures have been gradually rising since the 1970s and climbing at a faster pace for about the last decade, “2023 and ‘24 really stand out.”

In part, this is due to a recent El Niño, an event in which warming in the tropical Pacific Ocean boosts temperatures worldwide and causes knock-on weather effects. But Schmidt says it could also indicate an acceleration of human-driven global warming stemming from the fact that “we keep putting our foot on the accelerator of greenhouse gases.”

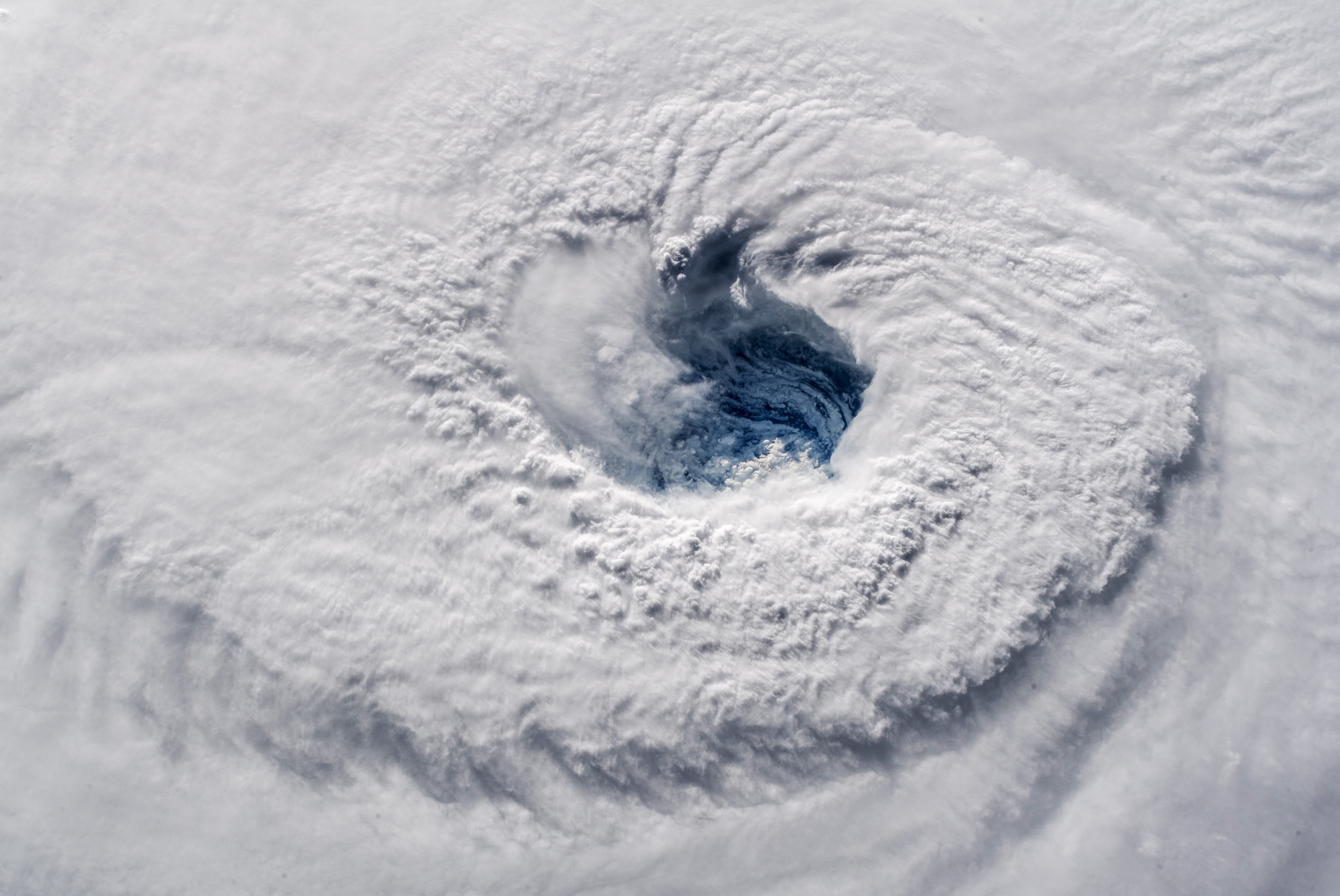

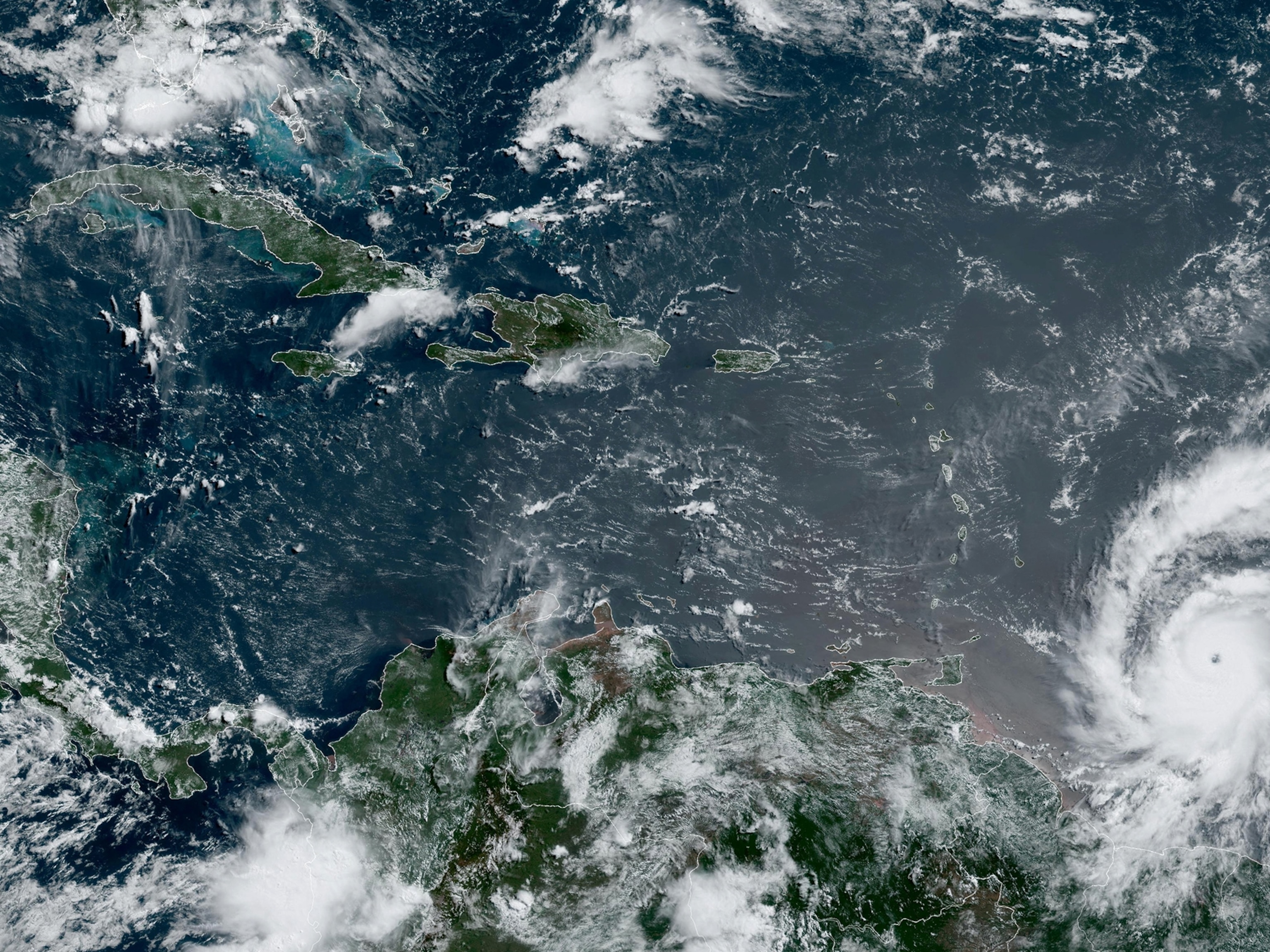

Either way, temperatures will continue to climb for as long as humans continue adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. Within the next decade, Schmidt says, the world is likely to permanently breach the 1.5 degree Celsius warming threshold, meaning the planet will consistently cross it most, if not all, years. From there, the future continues to look hotter, with current climate policies leading to roughly 3 degrees Celsius of warming by 2100. Along with the rise in temperatures, scientists expect we’ll continue to see an increase in extreme rainfall, excessively hot days, and climate-related disasters like wildfires and droughts.

“Every tenth of a degree, those things will become more intense and stronger,” Schmidt says.

The intergenerational challenge of climate change

While the changes to Earth’s climate system are profound, polling suggests most Americans aren’t very worried about the planetary crisis. Some still deny the basic facts of climate change. But for the majority of Americans who accept that human-caused warming is happening, other social and psychological factors, like shifting baseline syndrome, may be blunting their concern.

The concept of shifting baseline syndrome was first developed in the 1990s in the context of fisheries. Researchers found that younger fishers often perceived current fish stocks to be normal, even when older generations perceived them as drastic declines. Since then, scientists have found evidence that younger generations tend to have lower environmental expectations than their elders in a wide range of contexts, from biodiversity to natural resource abundance.

“In principle, shifting baseline syndrome is relevant to all environmental challenges,” says Soga of the University of Tokyo.

That includes climate change. In a recent review paper focused on how environmental baselines shift across generations, Soga and his colleagues found “many studies” indicating that people struggle to notice gradual changes in climate.

“Younger individuals, compared to older ones, are typically less likely to perceive changes in weather patterns, such as increases in rainfall or temperature,” Soga says.

Most of these studies were conducted in lower-income countries, and many focused on farmers. Soga suspects people in wealthier countries are “likely to be more affected by shifting baselines” because they tend to be less directly exposed to the impacts of climate change.

While there’s ample evidence that climate baselines can shift across generations, it’s unclear how much people are normalizing changes over the course of their lives.

A 2019 study of weather-related tweets found that Twitter users stopped finding extreme heat or cold remarkable when such events occurred for several years in a row. But other recent research suggests Americans are growing more concerned about extreme heat—and connecting the dots between the hot, dry weather they experience and climate change.

“Based on our research, people do notice that the weather where they live has changed over time,” says Ed Maibach, who directs the center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University. “If they have been in that place for long enough to have noticed.”

Are shifting baselines stalling climate progress?

Soga worries about how shifting baseline syndrome may be thwarting environmental progress.

If our collective understanding of what a “pristine” environment looks like deteriorates over time, that could decrease support for ambitious conservation policies and cause lawmakers to set weaker targets. It could also hamper peoples’ willingness to take action on their own.

“Studies show that individuals who strongly perceive environmental degradation are more likely to take conservation actions,” Soga says.

But Adam Aron, who directs the Climate Psychology and Action Lab at the University of California, San Diego, is doubtful that environmental amnesia is what’s holding back a mass mobilization to combat climate change. Even in places where many people are aware that a crisis is unfolding, he says, people aren’t necessarily taking action or demanding their elected officials do. If we want people to not only change their views on climate change but alter their behavior, Aron believes “non-analytic” approaches are needed.

“Non-analytic routes are social norms,” he says. “The people around me—my wife, my husband, my neighbors—are doing things. My neighbors have all put it up solar panels and electrified their homes. I'm going to do it, too.”