This stranded Venezuelan oil tanker is a potential disaster. Here's what we know.

After the U.S. tightened sanctions on Venezuela's state-owned oil company, more than a million barrels of crude oil were abandoned offshore.

A vessel filled with 1.3 million barrels of crude oil is floating 24 miles off Venezuela in the Gulf of Paria, a region home to economically important fisheries and vulnerable marine life. The FSO Nabarima, a stationary storage facility, has been pictured listing, rusting, and taking on water, sparking fears that it will spill its contents.

The crude has been stuck in the Gulf of Paria for almost two years, ever since the U.S. government imposed sanctions on Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA), the state-owned oil company that produced the oil. Italian energy company ENI is a minority stakeholder in the joint venture. The sanctions are intended to put pressure on the authoritarian regime of Nicolás Maduro, whom the Trump Administration does not recognize as the legitimate president of Venezuela.

The Nabarima holds five times more oil than what was spilled during the 1989 Exxon-Valdez disaster in Alaska. If even a fraction of it spilled, it would create an environmental disaster that extends into the Caribbean Sea and could last for years. According to recent reports from local officials in Venezuela and government representatives from the island nation of Trinidad and Tobago, which borders the gulf on the north, the ship is stable.

But an environmental watchdog group based in Trinidad and Tobago called Fishermen and Friends of the Sea (FFOS) remains skeptical and concerned that current efforts to remove oil from the tanker could result in spills. A video of the inspection was released by Trinidian state-owned media on October 23, but FFOS remains apprehensive of officials they say have been misleading them for months and is requesting further photographic evidence. The Nabarima, they add, is just the latest example of how the region’s oil industry is threatening the environment.

As of late last week the Maduro government has reportedly begun the process of taking the crude back to Venezuelan soil, a process that may in itself present an environmental hazard.

What’s at stake

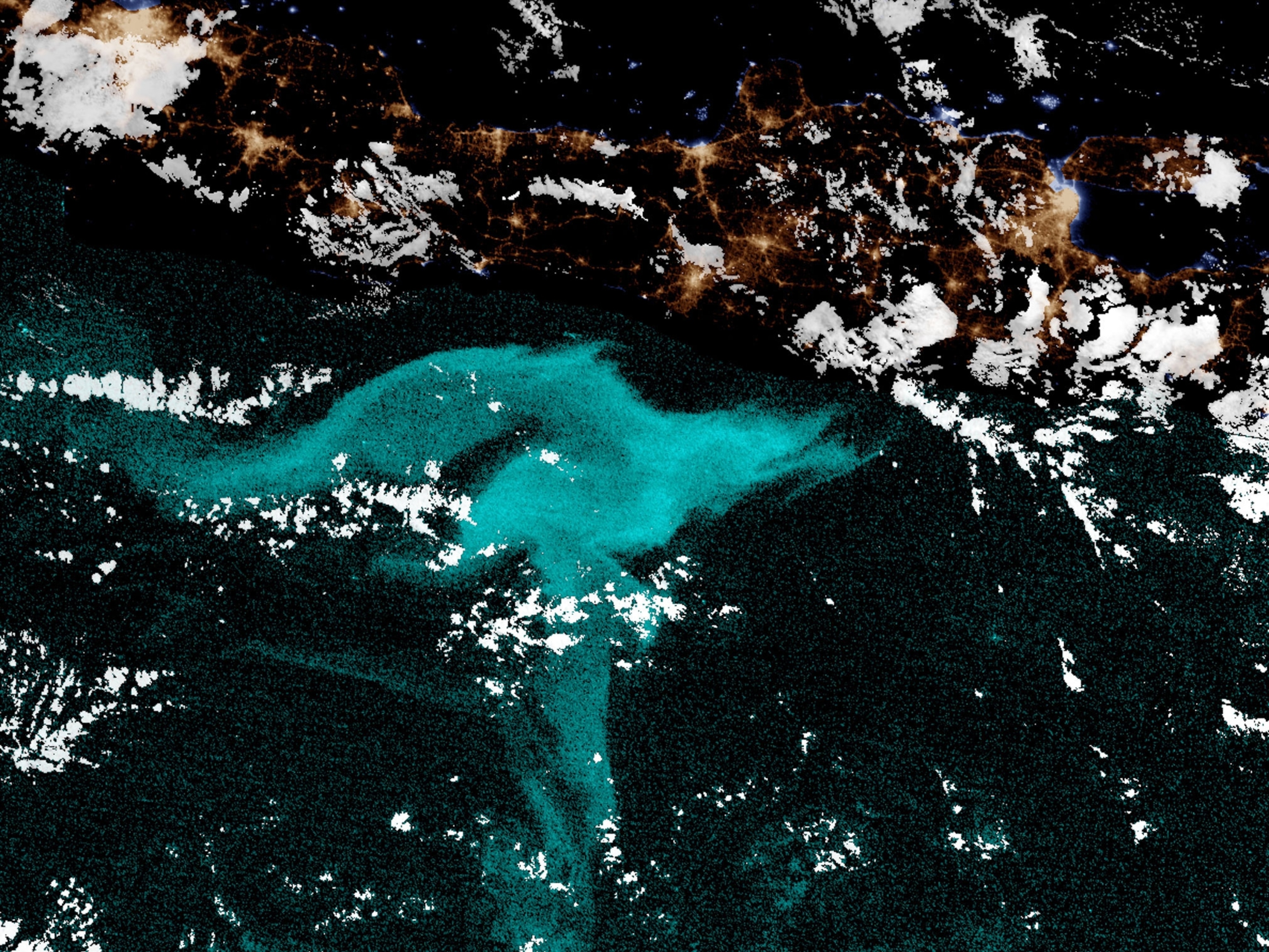

“We worked on the project 15 years ago for the environmental impact studies. We know the vessel very well,” says Eduardo Klein, an environmental scientist at Simon Bolivar University in Caracas, the Venezuelan capital. Klein tracks oil spills in the region using satellite imagery and radar and says he and his team can easily spot an oil spill from space.

He says the vessel, built by U.S. company ConocoPhillips and locked in place by eight large anchors, has not shown any signs of leaking or spilling its oil. Because he's familiar with how the vessel was constructed, he says, he's confident it's secure.

Based on several models Klein ran before the facility was put in place 15 years ago, a spill could damage the entire Gulf of Paria from the Venezuelan coast to the west coast of Trinidad and Tobago, and even spread through the strait between the two countries, out into the Caribbean Sea to the north.

What worries Klein most, he says, is the Venezuelan government’s ability to contain a spill. Twice earlier this summer, his images showed evidence of oil spills—one from a coastal refinery and one from an underwater pipe—that were never contained.

“When you spill oil, one of the first things you see is effort to contain it,” he says of the barriers and other containment measures visible via satellite. “None of this was evident in any of the images I saw. I do not think they are even prepared for even a minor spill.”

“The most potential damage could occur on mangrove forests,” says Jaime Bolaños-Jiménez, a marine ecologist at the Venezuelan Ecological Society for Marine Life, writing via email. “That spill could be catastrophic because mangrove forests are amongst the most productive ecosystems [on] the planet.”

Among the marine life that would be affected by the spilled oil are sea turtles, sea birds, sharks, and rays, along with commercially important shrimp, fish, and mollusks.

Depending on the size of a spill, the effects may linger for decades, long after clean-up efforts have ended, says Oceana marine scientist Sarah Giltz.

“It has been 30 years since the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska, and several of the local killer whale, seabird, and fish populations have still not recovered,” she says. “Ten years after the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, we continue to see impacts from the spill.”

Gary Aboud, FFOS’s corporate secretary of government, says an oil spill would endanger the livelihood of Trinidadian fishing communities that depend on the region’s healthy fisheries.

He and FFOS want both Caribbean and Venezuelan leaders to act immediately, but, he says, “at the very least we need information.”

In early of September of this year, PDVSA released a statement saying the tanker was in optimal condition.

Irene Petkoff is a former CoconoPhillips employee who, in the early 2000s, worked as the Corocoro oil field’s environmental manager, a job that entailed setting environmental standards for the oil field’s facilities, including the FSO Nabarima. She says it’s only through mismanagement and lack of maintenance that the tanker could see as many malfunctions as it has reportedly seen.

Petkoff claims she has heard unofficial reports that the ship’s main generator has been compromised, noting that if that’s the case, “It cannot be repaired.”

Given reports about the Nabarima and spills logged over the summer, she believes PDVSA has an epidemic of poor management.

What’s happening to the oil now?

In an interview with the Trinidad and Tobago Guardian last week, the country’s Energy Minister Franklin Khan said a vessel called Icaro was offloading oil from the Nabarima. The Icaro, however, is only capable of holding 300,000 barrels at a time and will require several trips over a month-long period to completely empty the Nabarima.

But the Italian energy company Eni, which owns the Nabarima in a joint venture with PDVSA called Petrosucre, says the oil must be removed quickly. It believes the vessel is stable for now, but several internal pumping systems are not functioning properly. In addition to collecting and storing crude oil, the Nabarima pumps seawater to coastal oil wells. It’s unclear if the malfunctioning pipes served this function or another.

“Eni is ready to perform activities to ensure the safe offloading of the Nabarima...using state-of-the-art solutions,” said a company representative via email. “The company will be able to proceed only after approval of its plan by PDVSA...and upon formal assurance by the competent U.S. authorities that the mentioned activities bring no sanctions risk either for Eni and its contractors.”

PDVSA did not respond to requests for comment. The U.S. sanctions prohibit American companies from working with PDVSA and threaten penalties for foreign companies who do.

A spokesperson for the U.S. State Department said by email that Eni would not be penalized for conducting repairs to the Nabarima but declined to confirm that the Italian company had a green light to remove the oil and return it to Venezuelan soil.

“The illegitimate Maduro regime has ignored this issue for some time and we are not able to assess the Maduro regime's ability to safely perform the necessary repairs and offload oil,” the spokesperson said.

Opposition government in Venezuela expressed similar concerns last Friday, saying the Icaro is too old and ill equipped for what they described as a “high-risk” operation. The Maduro government declined help and newer equipment offered by the European Union.

On its website, PDVSA disclosed it has logged more than 7,000 oil spills, but it did not say since when. The country is reportedly seeing more spills as Venezuela’s government, oil industry, and wider economy deteriorate.

The timeline

The Nabarima does not have an engine; it was built as a storage facility from which a tanker collects crude oil. According to Eni, the 15-year-old vessel would be in stable condition if maintenance were regularly performed. Whether the Nabarima has in fact been getting routine maintenance is unclear.

FFOS, the watchdog group, says it has been concerned about the Nabarima since sanctions were imposed, but it wasn’t until August of this year that it received images showing water flooding the ship and the vessel tilting to the side. By mid-August, oil workers employed by PDVSA began protesting labor conditions and calling attention to the Nabarima, saying it was deteriorating from lack of maintenance. Yet on September 2, a representative from PDVSA tweeted that the ship was in good condition.

“We were led to believe everything was okay,” says Aboud. “But our partner (in Venezuela) kept informing us of the contrary.”

FFOS declined to name their Venezuelan partner, another environmental watchdog group, citing concerns for their safety.

On October 13, FFOS received pictures showing the Nabarima listing significantly to one side. three days later, Aboud and his FFOS colleagues went to see the vessel in person and observed what they estimated to be a 25-degree tilt. On October 19, the director for a Venezuelan petroleum workers union tweeted that the Nabarima had extensive problems with its machinery that were “permanent.”

Aboud took to social media to relay his concerns, which were amplified by climate activist Greta Thunberg, and on October 20, a team of government officials and engineers from Trinidad and Tobago and Venezuela inspected the ship, reportedly finding nothing amiss.

FFOS says it remains skeptical until photos from the tour are disclosed. The environmental group intended to revisit the ship, but says that is now impossible since the ship is being guarded by Venezuelan authorities.

Correction: A previous version of this article stated the FSO Nabarima's crude oil was headed for U.S.-based refineries.