Why your kid’s dark pandemic play is normal—and healthy

Throughout history, children have used pretend play to cope during challenging times.

When the pandemic first began, ambulance sirens pealed around the clock in Lela Moore’s Brooklyn neighborhood. To help her vehicle-obsessed three-year-old, Ned, understand the situation, they began reading books about first responders and other emergency workers.

“The refrain in the book was ‘Help is on the way,’” Moore says, which helped explain to Ned that sirens meant someone was being helped. The two would clap as the engines sped by.

As the weeks passed, Moore noticed that when Ned played with his fire or other rescue trucks, he’d repeat ‘Help is coming, it’s on the way!’ gather his Lego people, and clap for the trucks as they passed.

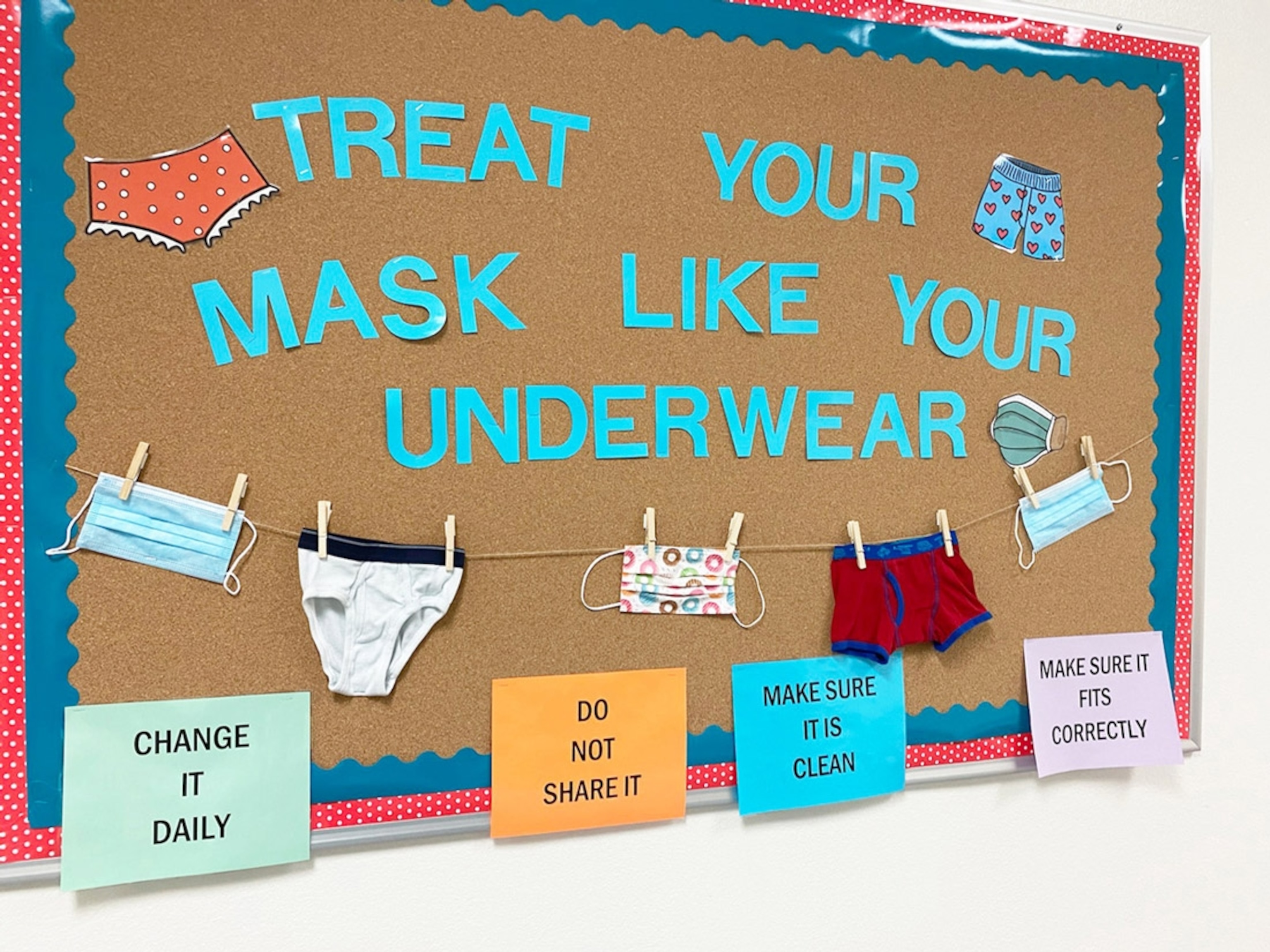

Ned is not the only kid making sense of the pandemic with pretend play. Parents, teachers, and child psychologists are reporting similar behavior, like strapping masks onto teddy bears, taking dolls’ temperatures, or even playing “COVID tag” together in the yard.

If it seems a bit macabre, it’s actually incredibly normal—and even healthy, says Sandra Russ, distinguished professor of psychology at Case Western University, who researches pretend play in children. In fact, throughout history, play has been a way for children to cope with potentially traumatic events and comprehend a sometimes dangerous world.

“Pretend play is where children express their fears and worries,” Russ says. “This is especially true when it comes to things that are scary—it’s going to come out in their play.”

Why play helps kids deal

When adults are stressed or upset about something, we talk about it. But kids don’t yet have the skills to do that.

“Instead, making a game out of tricky topics helps children process the feelings that arise from a safe distance,” Russ says. “And it can help them problem solve in ways that don’t necessarily require the sophisticated words they might otherwise need.”

For instance, a child who’s giving a doll a shot may be working through a fear of needles. “By having the doll be the one who’s afraid is distanced—so the emotion is not as intense,” Russ says.

In playtime, the child controls of the narrative and the action—so if anything gets overwhelming, they can stop. Fun and games, even when centered around serious topics like death or war, renders the subject safe. “Children are able to rehearse ways to handle things and make up happy endings, too,” Russ says.

Scientists have even found that the ability to engage in imaginative play might help children deal with future traumatic or challenging events. “Pretend-play ability predicts coping over time,” Russ says.

For instance, she points to research indicating that children who engaged in pretend play adjusted to and had less fear and anxiety during hospital stays, compared with children who didn’t engage in pretend play.

Not enough studies have been done yet to ascertain what’s actually occurring in the brain while children are engaging in this sort of play. But Laura Phillips, a neuropsychologist with the Child Mind Institute in New York City, says scientists can look to what’s going on in adult brains when they’re in creative problem-solving mode. Based on MRI research, Russ says, mind-wandering and improvisation activate a different area of the brain from logical, critical thinking. When adults are trying to solve a problem, they go back and forth between these modes.

Pretend play involves both improvisation and critical thinking. “Kids [likely] go back and forth between these cognitive processes, just like adults do in creative activities,” Russ says. “It’s reasonable to think that kids’ brains would function much in the same way during their playtime.”

The history of playing to cope

Using play as a way to deal with complex circumstances is something children have done throughout history, according to Daniel Feldman, a professor of literature at Bar-Ilan University in Israel who’s studied children’s play during wartime.

For instance, he notes that during the Civil War, boys pretend-marched while dressed as soldiers; girls imitated the nurses of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, which provided medical care to soldiers. World War I brought an influx of miniature lead soldiers, artillery pieces, and other military gear to children’s toy chests. And play therapy pioneer Anna Freud (the youngest child of Sigmund Freud) observed that children who were sent to live in “War Nurseries” outside London during World War II frequently played war games, especially games simulating the air raids of the Blitz.

And COVID-19 is not the first disease to inspire gameplay in children. The concept of avoiding the “cooties” actually came about in the 1950s, during the peak of the polio epidemic. In her book Once Upon a Virus, Indiana University professor Diane E. Goldstein writes of a similar version reported in the 1980s and ’90s, when U.S. children played “AIDS tag” as a way to work out their fear of the mysterious new disease.

But children’s games can take on a much more sinister feeling when kids are truly threatened. For instance, historians have documented cases of enslaved Black children in the United States acting out the atrocities they and their families faced. (Feldman even wrote about two enslaved children who played “auctioneer”—one standing on the block, the other conducting a mock auction—in an actual slave house in Richmond, Virginia, after witnessing something similar earlier in the day.) And Jewish children imprisoned in Auschwitz-Birkenau were documented playing games such as Roll Call, Doctor, and even Gas Chamber.

“These games mimicked a ghastly reality,” Feldman says. “But more importantly, they offered a vital means by which children comprehend reality. Children play as a means of trying to understand their world, which is sometimes hostile and often confusing.”

What parents can do

If you notice that the pandemic has crept into your own kids’ playtime, Phillips advises simply letting it happen.

“It’s a healthy, adaptive sign that helps them gain control and work through the experiences that may be swirling around them,” she says, recalling that she once observed her two-year-old sticking crayons into her teddy bear’s nose like a COVID test. “There was no anger, no fear. She was just processing her experience in the best way that she can.”

Russ advises against forcing yourself into their play in case they become self-conscious and stop. Instead, just follow their lead: The youngest kids may want you to roll up your sleeves and join in their teddy bear vaccination session; older ones may not want you to get involved.

If your child’s COVID play does seem angry or aggressive, Phillips recommends asking age-appropriate questions about what they might be acting out or how they’re feeling.

“Try to make these open-ended questions, since you don’t want to put your own thoughts on what might be happening in their scenarios,” she recommends.

Let them talk freely; if necessary, supply some age-appropriate language to help them make sense of the situation. To allay fears in a reassuring yet truthful way, Russ recommends saying something like, “Let’s talk about what we can do to avoid getting sick.”

If you notice that your child is extremely anxious during play or repeating the same thing over and over in a distressed way, Russ says it might be time to become more involved in helping them process their feelings, or even seek help from a mental health professional.

As for Lela Moore’s son, he’s working through his pandemic worries by lending a hand.

“Ned was a firefighter for Halloween,” she says. “He never really talked about putting out fires—just always how he was going to help people.”