How you can change your body's threshold for pain

Everyone experiences pain differently. But experts say there are things you can do to better cope with it.

Pain likely began as a curious evolutionary advantage, helping organisms react to injury quickly and escape while also teaching them to avoid similarly harmful situations in the future.

Nowadays, most humans would go to great lengths to avoid feeling pain. But there are some who dedicate their lives to conquering the sensation, pushing their minds and bodies beyond typical physical limits to achieve dangerous, hair-raising feats.

It’s this complex relationship with pain and endurance that renowned magician David Blaine explores in his new documentary series, David Blaine Do Not Attempt, produced by Imagine Documentaries. Traveling the world in search of the extraordinary, Blaine discovers how performance can reinvent fear and influence our perception of pain.

David Blaine Do Not Attempt premieres on National Geographic on March 23 and streams next day on Disney+ and Hulu.

While most people aren’t juggling fire or diving nearly naked into freezing lakes, they are managing pain in everyday life.

“We develop different reactions, different emotions, different behaviors based on in which context pain is perceived,“ says Gregory Scherrer, an associate professor of cell biology and physiology at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the UNC Neuroscience Center. “This is why pain is subjective.”

Here’s what we know about pain and its complicated relationship with pleasure—as well as some basics on living with pain in daily life.

How pain tolerance develops and evolves

From getting a cavity filled to getting a tattoo or having your ears pierced, even the most mundane life experiences are coupled with an expected amount of discomfort. Depending on the way our bodies interpret pain signals, these sensations could feel surprisingly pleasant, as intense pain and pleasure do activate some of the same brain circuits.

This phenomenon can manifest in several ways including “runner’s high,” wherein the body releases endorphins in response to the feeling of prolonged physical exercise, causing feelings of temporary bliss and pain relief. You can also blame this tricky biological reward system for why people love spicy foods.

Despite how hard pain can be to push through, prevailing over it can be especially empowering, says Anna McNuff, a British author best known for cycling through every U.S. state and running the equivalent of 90 marathons through Britain barefoot.

Certainly, having power over painful experiences is a refreshing kind of freedom. “I can back off a little bit or sit on the knife edge between what is painful and what is not,” says McNuff. “If I think about pain, I like it because it makes me feel alive.”

Questions about nature vs. nurture muddies scientific insights into natural pain tolerance. After all, it's hard to tell where a person’s sensitivities come from, as a multitude of factors influence our day-to-day pain tolerance, including genetics, sex, and even the amount of sleep we may get. Women, for example, are more sensitive to pain, a potential side effect of having more hormones than their counterparts. On the flip side, men are said to have higher pain thresholds but be less likely to report their aches and pains than women, which could be due to how society teaches them to suppress their emotions.

Additional research has found that our pain threshold also changes as we age, increasing as an adult and into our later years. This could be due to youths being more curiosity-driven and having fewer negative experiences to draw on than they would later, says Scherrer. “If pain was not a bother, we wouldn't be careful with our body,” he says. “We would do crazy things and we wouldn't live long.”

Surviving pain

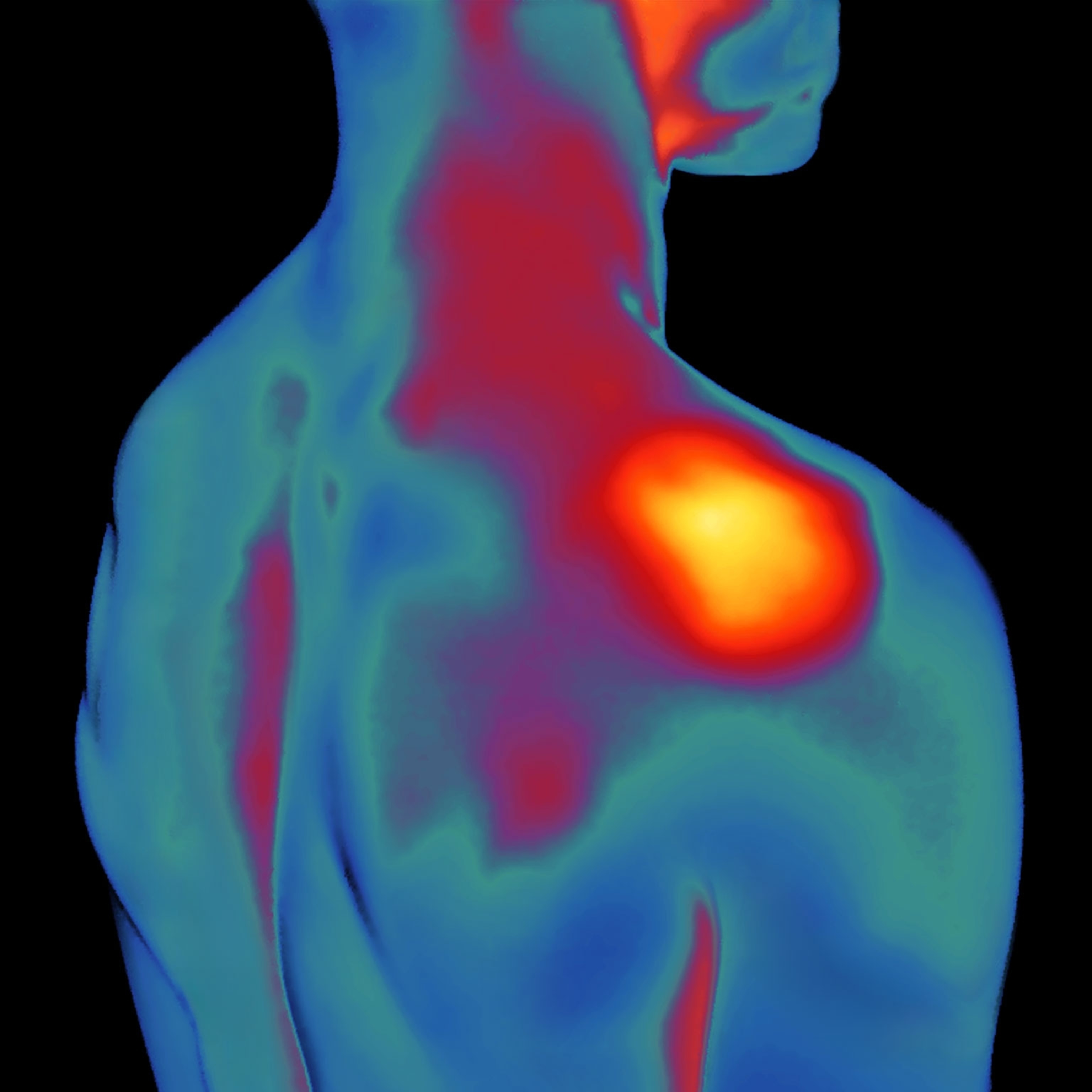

Having a high pain tolerance can often feel meaningless in the face of chronic pain, which when lasting more than three months, can severely restrict free time or work activities, and negatively impact a person’s quality of life.

In the U.S., about 21 percent of the population — more than 51 million adults — live with this type of long-term pain. Globally, billions are estimated to suffer from chronic pain, and many countries are seeing population-wide escalations of pain and disability.

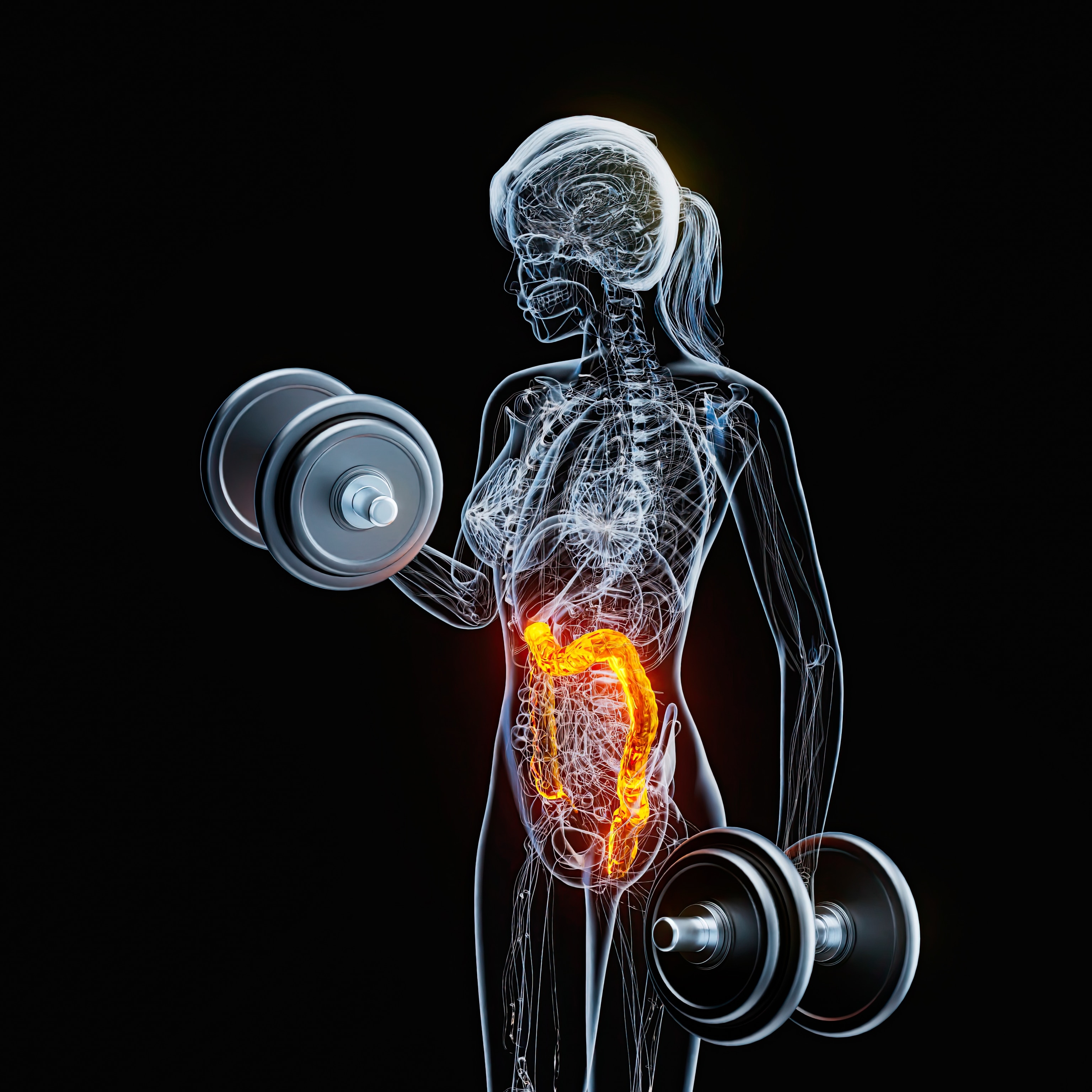

Exercise therapies have also proved a powerful tool in fighting chronic pain. Some studies, for instance, have linked certain types of movement, like yoga, to the successful prevention and treatment of several chronic conditions, including migraines and low back pain.

People have also found meditation, spirituality, and religion have helped them cope. In fact, some studies have shown that access to spiritual resources can lead to improved patient pain tolerance against acute and chronic pain, despite not doing much to lessen their suffering.

Still, pain does have its uses. It’s an important signal that tells you when your body is stretched to its limits. And sometimes, forging through pain can help a person grow stronger.

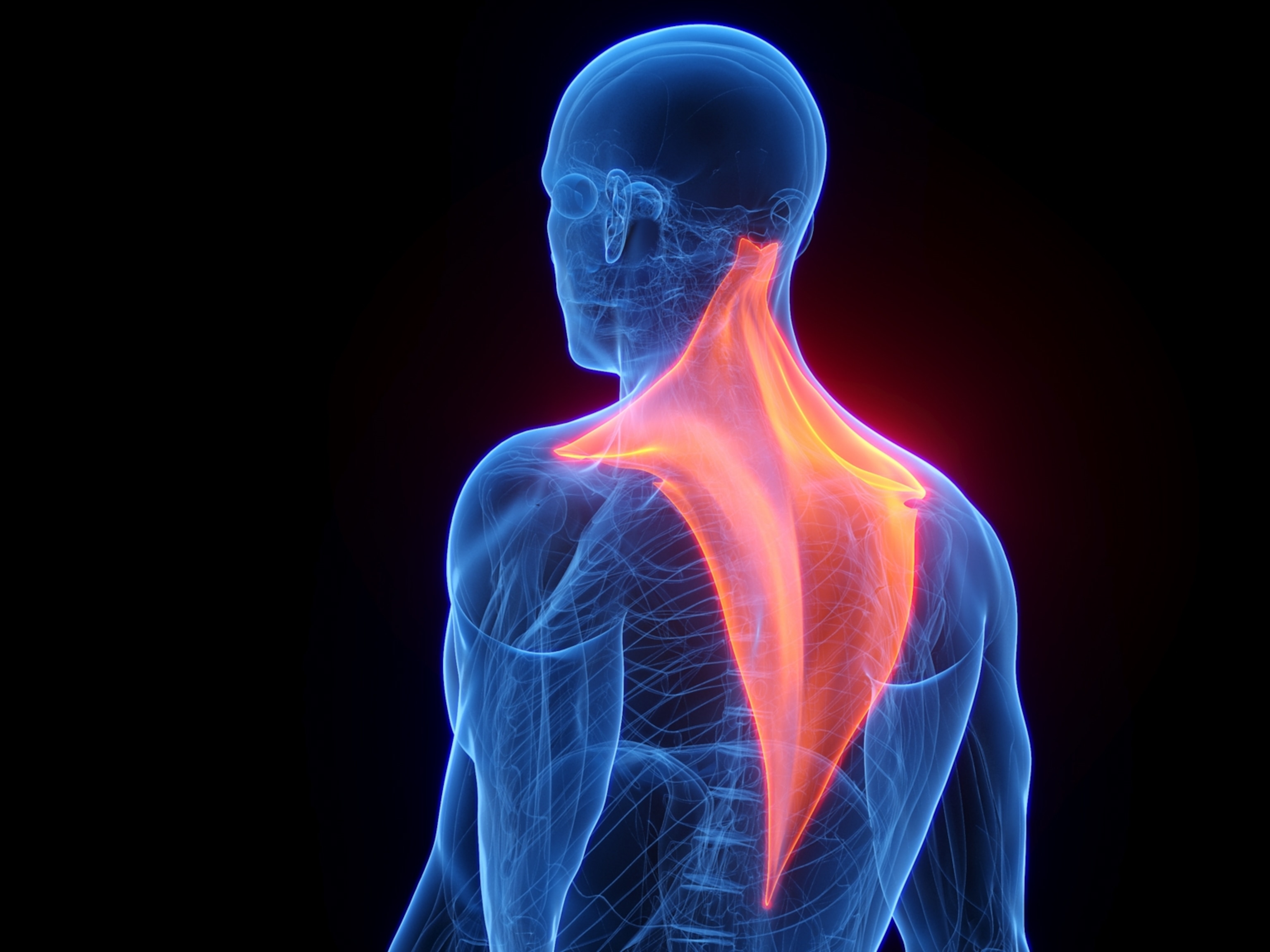

“Training for something is as much about building mental confidence as it is physical resilience,” says McNuff. In her experience, much of the prep involved in overcoming pain and failure includes being aware of how you may respond to stress and injury.

“People often view getting injured while on the road to training for a big adventure as a terrible thing, but actually it’s a chance to better understand your body,” says McNuff. “At the end of the day no one knows your body better than you, and the more you can do to push it, prod it, poke it and understand it, the better.”

Ultimately, because pain and pleasure are intimately intertwined in our social fabric, Brock Bastian, a professor of psychology at the University of Melbourne, suggests that existence wouldn’t be as satisfying without either sensation at the helm. “In small ways, we're always seeking out something that challenges us, something that stretches us,” he says. “Experiencing some pain is a really important part of a happy and healthy life.”