10 years later, see how Superstorm Sandy changed the Northeast

Elevated beach homes, walls of sand dunes, and new urban parks show how New York and New Jersey have rebuilt after one of the costliest weather disasters in U.S. history.

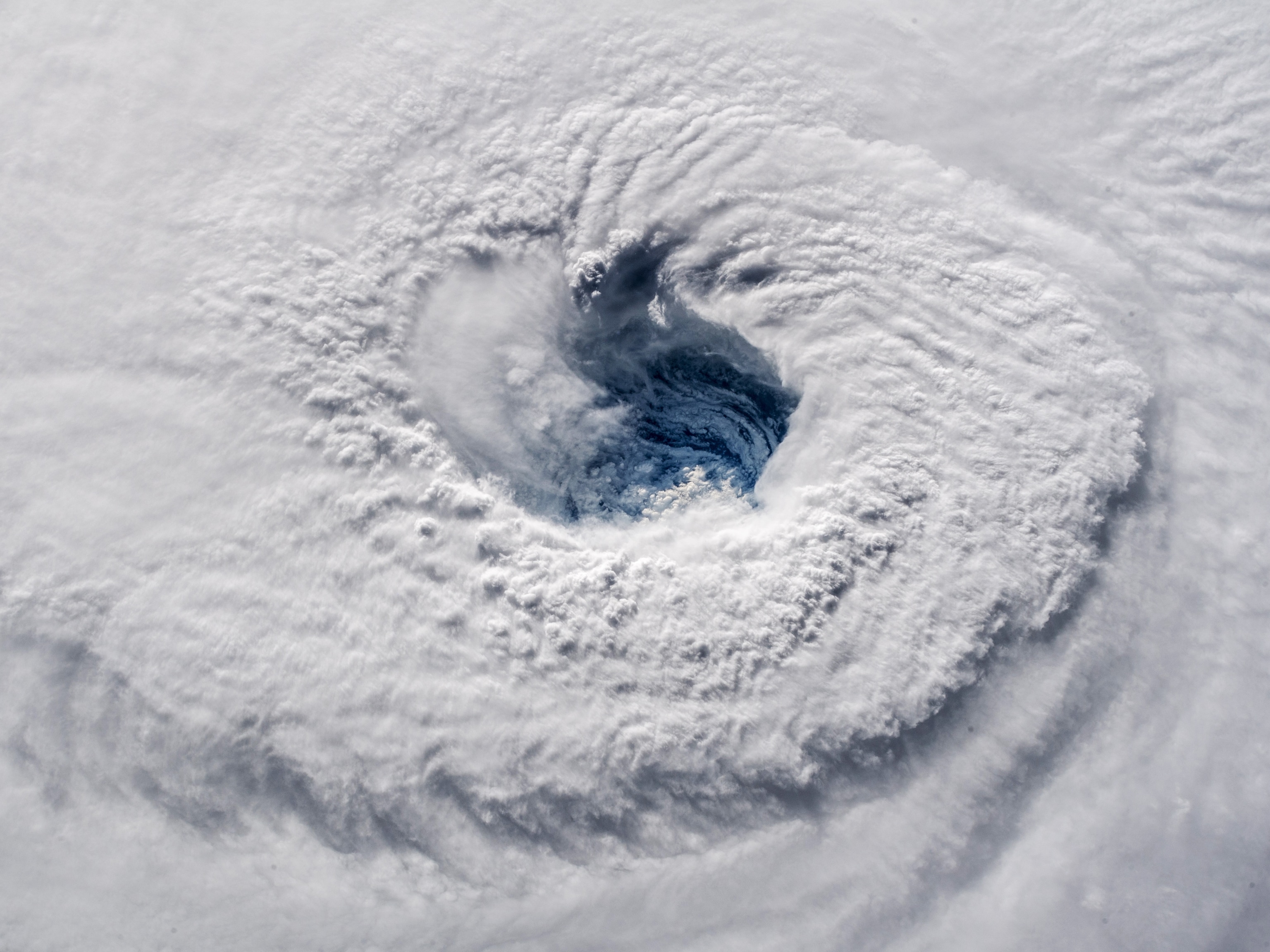

When Superstorm Sandy made landfall near Atlantic City, New Jersey, on October 29, 2012, it was unlike anything residents in the storm’s path had ever seen.

After a weeklong journey up the East Coast, Sandy was no longer technically a hurricane, but it collided with a powerful winter storm and created a behemoth “super storm” that pummeled coastal areas with 80-mile-an-hour winds and a storm surge as high as 14 feet.

The storm killed over 100 people in the U.S., destroyed 600,000 homes, and knocked out power to eight million residents. It was the fourth costliest storm of its kind in U.S. history, with damages totaling $81 billion, and it showed how vulnerable the region was to natural disasters.

“When Sandy hit, New York City had zero coastal protections, says Daniel Zarrilli, special advisor for climate and sustainability at Columbia University. “For a city with 520 miles of coastline, it’s almost shocking we didn’t have those interventions in the past.”

The destruction left by Sandy was a wake-up call. It pushed residents, city planners, and politicians to protect the coast from present threats and those expected in the future as a result of climate change.

Warming temperatures are making hurricanes stronger, rainier, and more likely to strike farther north. And as seas rise—seas along the coast of New York have risen nine inches since 1950—coastal flooding is becoming deadlier.

Planners knew they couldn’t rebuild the same structures the same way. They would have to be smarter, tougher, and higher off the ground.

“I credit Sandy as that pivotal moment that not only launched billions of dollars of resilience investments across the city,” says Zarrilli. “It also provided the spark for a whole range of other climate policies.”

Ten years later, results of those policy changes are visible. New building codes have lifted beach homes several feet. Dunes on the Rockaway Boardwalk and an oyster reef off the coast of Staten Island stand ready to blunt the force of storm surge. In the Oakwood Beach neighborhood, government-funded buyouts have emptied a housing development that’s now becoming a wetland, returning to nature what couldn’t be protected.

Yet many reconstruction projects remain unfinished. Plans to create a buffer of parks around lower Manhattan have been stalled by controversy. And at Red Hook West in Brooklyn, the second largest public housing complex in the city, construction is still a very visible, audible, and unwelcome reminder of Sandy.

“I can’t believe it’s 10 years already,” says Karen Blondel, president of the Red Hook West tenant association. “You go outside and there are double parked vehicles, trucks delivering materials. It’s chaos.”

Blondel says she and other residents have put up with years of construction so loud “you couldn’t talk or be on the phone.” But they’re hopeful that if they’re struck by a future storm, their buildings won’t flood and lose power for a month, as happened during Sandy.

“Most people,” Blondel says, “have been extremely tolerant because of hope that in the end they can stay in beautiful Red Hook.”