Easter Islanders’ Weapons Were Deliberately Not Lethal

Researchers say the weapons of Rapa Nui were actually lousy battle tools, and the islanders wanted it that way.

Few stone monuments are as recognizable as the moai of Rapa Nui (Easter Island), and few cautionary tales are as widely repeated as the sorry fate of the Polynesian society that crafted the monumental stone sentinels. The drive to create these enigmatic and enormous monuments resulted in widespread deforestation, the story goes, which in turn led to systematic warfare over increasingly scarce resources and, ultimately, complete societal and economic collapse before the arrival of the first Europeans in 1722. (Read more: How did islanders move the moai?)

But now the most common—and most unremarkable—artifacts on the island are shifting the debate about whether the Rapanui virtually wiped themselves out in a frenzy of organized violence before European contact. (Take a photographic tour of Rapa Nui.)

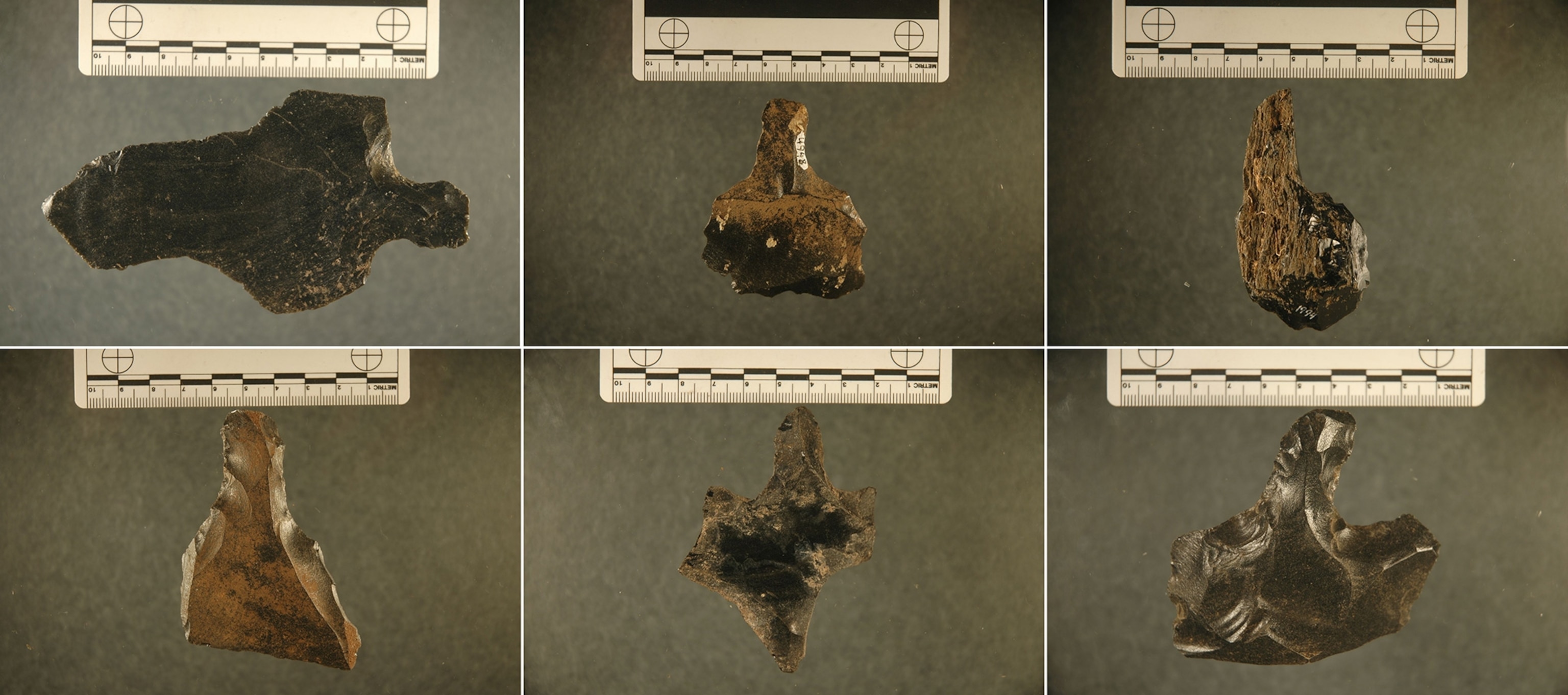

By 1877, only 110 Rapanui were alive on the island, and it was around this time that European ethnographers began to collect their oral histories about the earlier wars that ravaged their community. Since then, researchers have suggested that the thousands of small, three-sided, stemmed obsidian tools found across the island were the weapons employed in these battles. (Watch the moai "walk.")

In his 2005 book Collapse, former National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence Jared Diamond characterizes the tools, known as mata'a, as leftovers "from an epidemic of civil war." The humble mata’a are even touted as an example of "stone-age weapons innovation" in a publication by the U.S. government’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency.

There’s no organized violence and no mass killing.Douglas Owsley, Physical anthropologist

However, a new study provides evidence that mata'a could not have been used as lethal weapons for systemic violence. This adds to a growing argument among Rapa Nui scholars that the warfare described in later accounts actually never happened, and that while the islanders certainly suffered from the effects of deforestation and environmental degradation, the only "collapse" occurred following contact with outsiders, who brought disease and slavery to the Rapanui.

Furthermore, the authors of the study argue that making the mata'a inefficient as killing tools was a deliberate decision by the isolated island community, which quickly realized that lethal internal battles would eventually leave everyone dead.

"No more lethal than any other kind of rock"

A research team led by National Geographic grantee Carl Lipo of Binghamton University analyzed more than 400 Rapa Nui mata'a to see if there are any consistent patterns in shape and size that can suggest a particular function for the blades — say, a long, narrow, pointed form that can effectively penetrate flesh and pierce organs. While the mata'a ranged from 2.4 to 3.9 inches (six to ten centimeters) in length and width, the shapes varied so continuously that they were unable to identify any category of mata'a with a consistent form that would indicate design for a specific purpose. Rather, the vast variety of shapes indicate that mata'a most likely served as a multipurpose tool for all aspects of daily life on the island, including food cultivation and processing.

While the sharp edges of mata'a were ideal for cutting and scraping (a fact supported by earlier use-wear studies), their weight and asymmetry made them ineffective for inflicting deadly stabbing wounds, Lipo concludes, calling mata'a "no more lethal than any other kind of rock."

In a recent study of skeletal material from Rapa Nui, a team led by Douglas Owsley, Division Head of Physical Anthropology at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, found that only two of 469 skulls had trauma that could have been inflicted by the slice of a mata'a. The vast majority of injuries resulted from blunt-force trauma from thrown rocks, a popular form of attack on Rapa Nui documented by European visitors who experienced such violence.

Archaeologist Paul Bahn, a proponent of the traditional collapse theory whose research has been cited extensively by Jared Diamond, dismisses the idea that mata'a could not have been used as effective tools of war. "Mata'a could certainly inflict lethal wounds," he says, "This is essentially a slashing tool. You could do terrible things to people without leaving a trace on bones."

Owsely is more circumspect. "In my experience, when you’re really trying to do someone in, you’re going to hit them in the head," he observes, "and a slash across the face would be picked up in the skeletal evidence."

The reliance on ethnographic accounts collected centuries after events allegedly occurred has also been a continual issue among Rapa Nui scholars. "This was a small population on a small island. Everyone knew everyone," Owsley observes. "Even the death of a few people, shared and repeated across the island over and over again can eventually make violence sound much more pervasive than it actually was."

A Tacit Understanding Not to Kill?

This is not to say that life on Rapa Nui was conflict-free. "The Rapanui certainly engaged in violence—you can see all of the healed injuries on the skeletal remains—and as sharp objects, mata'a could be used in many threatening ways," says Lipo. But why did the islanders, who had the technological skill to erect almost a thousand 70-ton moai, fail to develop efficiently lethal weapons to battle one another?

"It's not as if they never figured it out, that's crazy," Lipo says. "They chose not to."

The inefficiency of mata'a as killing tools was a deliberate decision by the isolated island community.

According to the 2012 book The Statues That Walked, written by Lipo and his colleague, University of Oregon anthropologist Terry Hunt, it simply didn’t pay to escalate conflict to levels that resulted in lethal violence on tiny, isolated Rapa Nui, a 64-square-mile (166-square-kilomter) island that’s 1,500 miles (2,414 kilometers) from its closest neighbor.

"This island was their entire universe," Lipo explains, "and lethal violence only pays if you can do it anonymously, kill and leave, or kill everyone else. Otherwise you’ll face the consequences of killing sooner or later."

The Rapa Nui community quickly figured this out, he theorizes, and developed ways to compete with one another that would not escalate into endless tit-for-tat massacres that would ultimately leave everyone dead.

Rapa Nui is always treated as a cautionary tale, but I think it’s the opposite.Carl Lipo, Anthropologist

The current skeletal analysis appears to support this idea. "The bone fracture data doesn’t conform to periods of intense violence described in the ethnohistoric accounts," says Owsley. "There’s no organized violence and no mass killing."

Lipo urges a more critical look at the standard Rapa Nui story of environmental degradation, conflict and decline. "Science means we need to understand what really happened," says Lipo, "and I think there’s a lot of great lessons to learn about what it takes to be successful on a remote, tiny island where you have to work together."

"Rapa Nui is always treated as a cautionary tale, but I think it’s the opposite."

Follow Kristin Romey on Twitter