Harriet the Spy: How Tubman Helped the Union Army

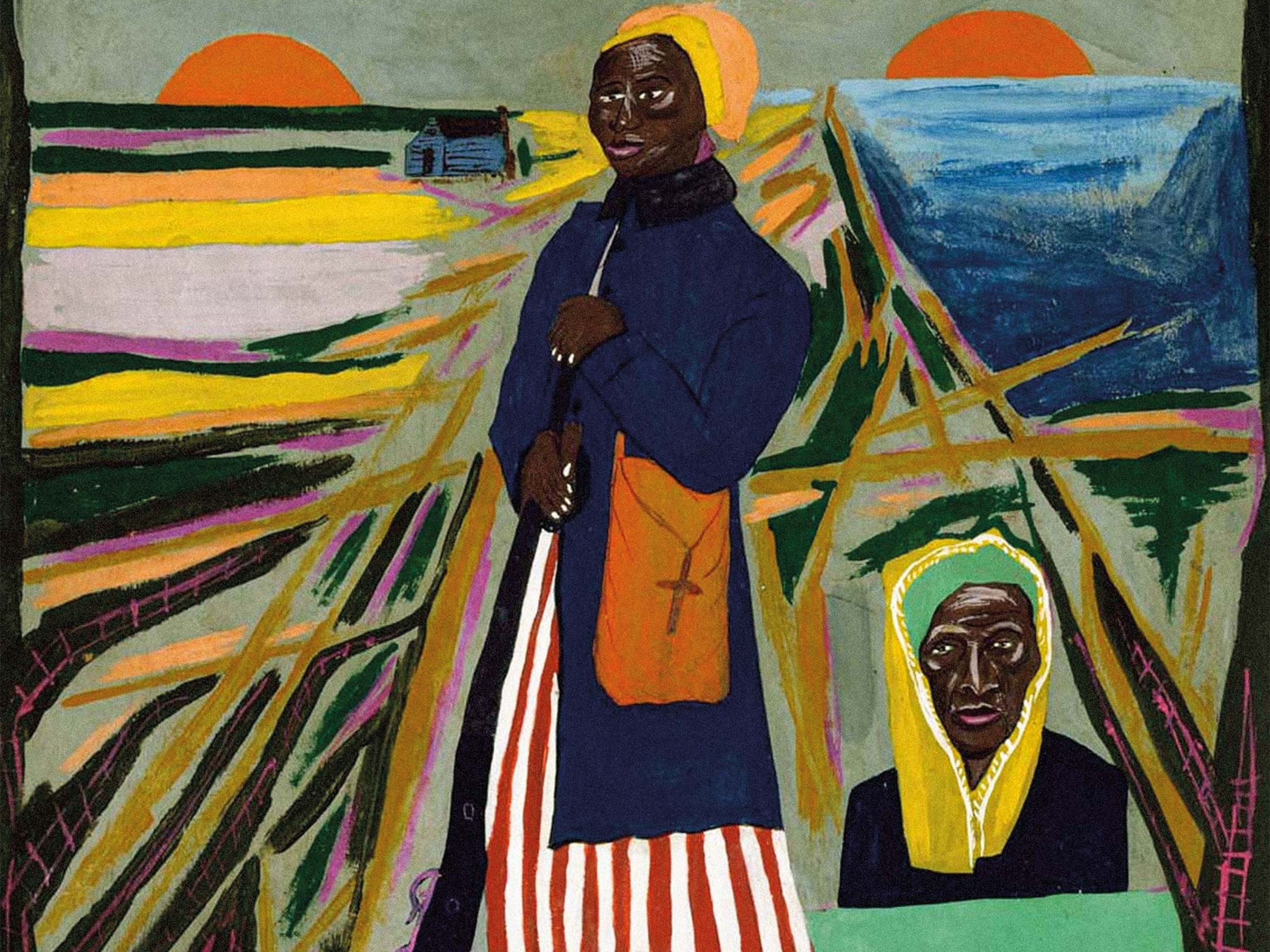

Most people know her as a former slave that freed others. During the Civil War, Harriet Tubman was also a secret spy and military leader.

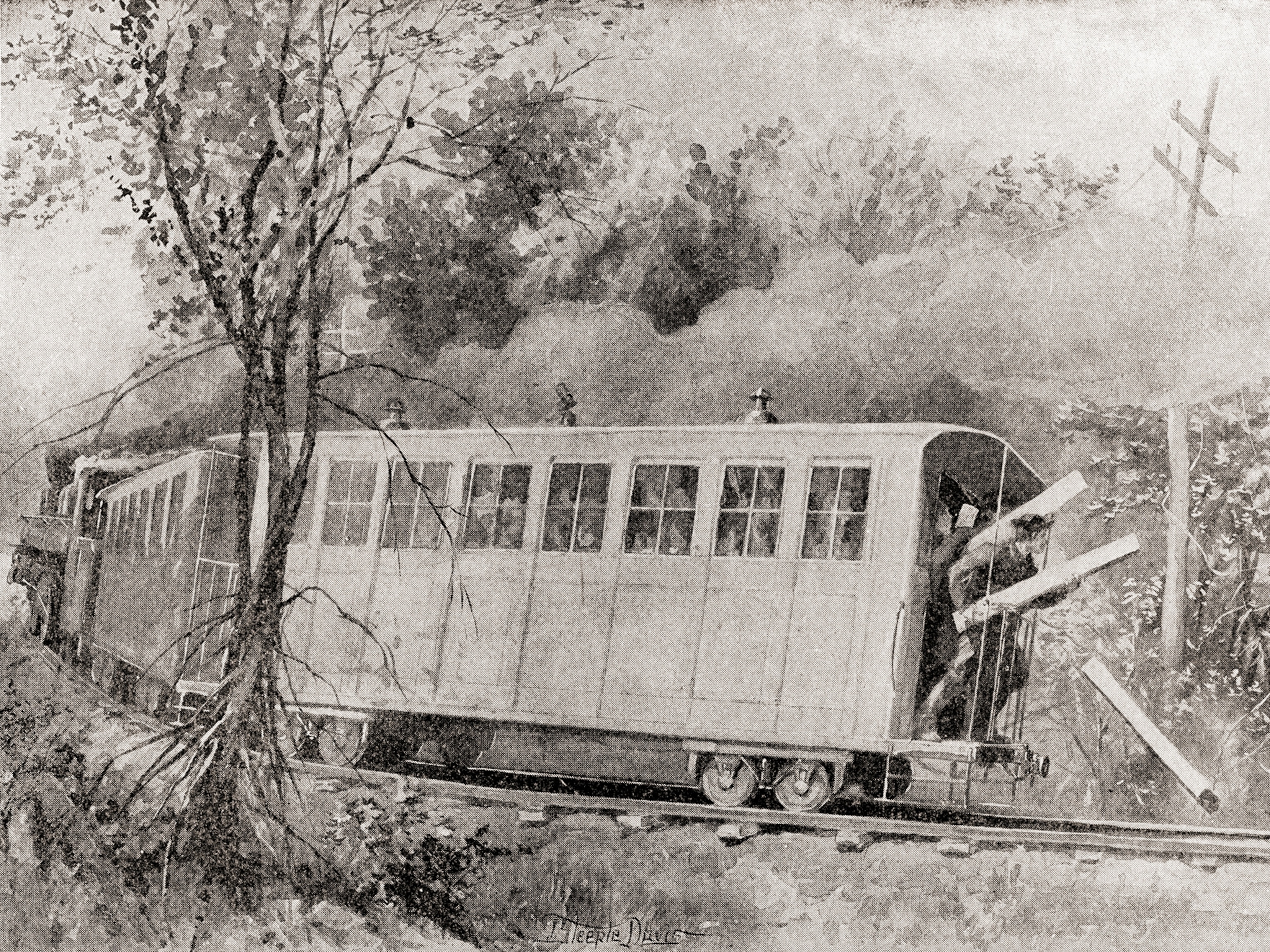

In 1863, Harriet Tubman led soldiers with Colonel James Montgomery to raid rice plantations along the Combahee River in South Carolina. They set fire to buildings, destroyed bridges, and freed many of the slaves on the plantations.

When slaves saw Tubman’s ships with black Union soldiers on board, they ran towards them as their overseers helplessly demanded that they stay. One overseer reportedly yelled “See you to Cuba!” (At the time, Confederates were trying to spread a rumor that the Union would ship runaway slaves to Cuba to work on sugar plantations.)

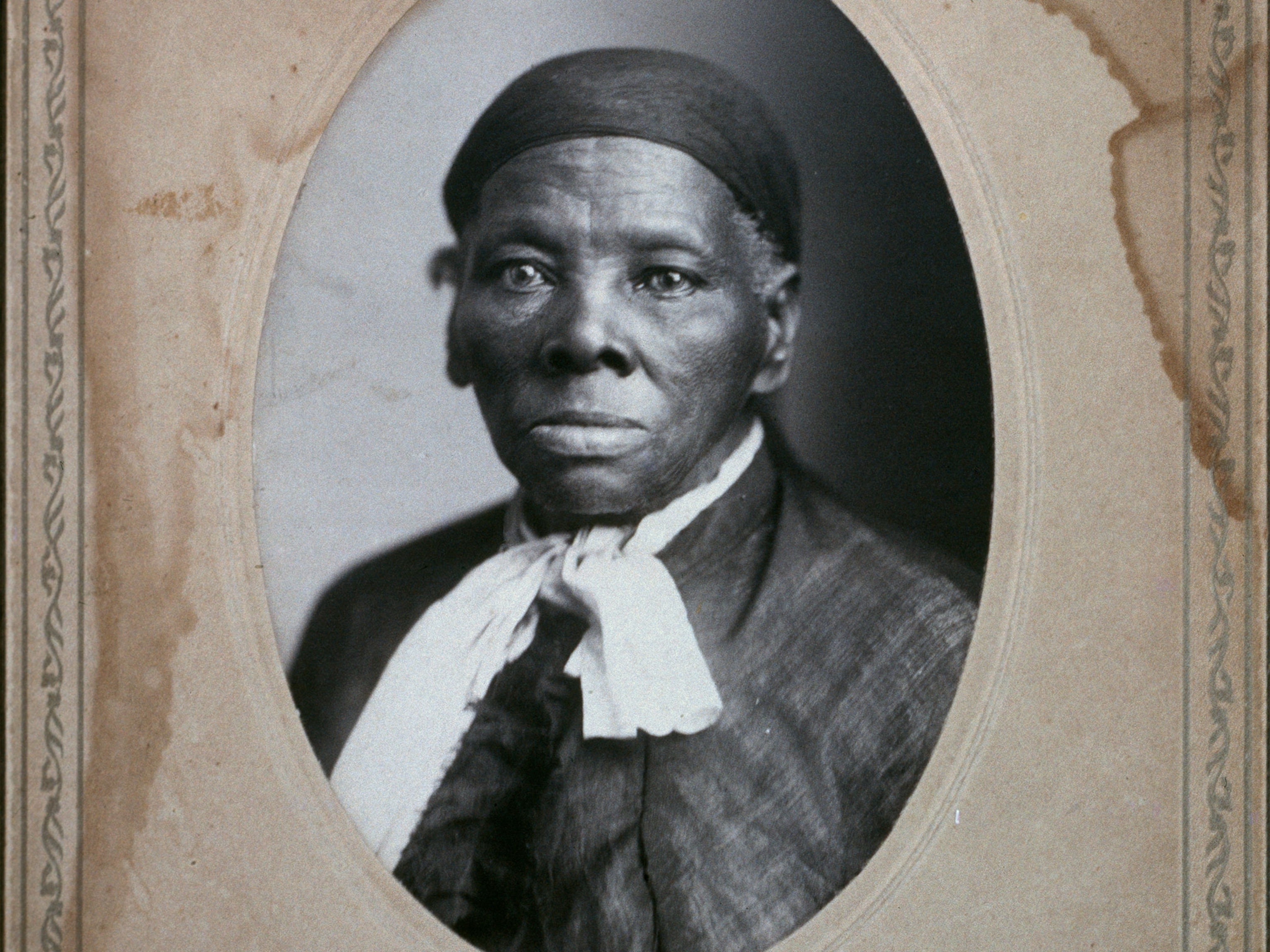

Tubman, who will replace President Andrew Jackson on the front of the $20 bill, is most known to Americans for leading hundreds of slaves to freedom on the Underground Railroad. But she also played a crucial and pioneering role in the Civil War.

In addition to being the first woman in U.S. history to lead a military expedition, Tubman—whom John Brown called “General Tubman”—was a Union army spy and recruiter.

“She was one of the great heroines of the Civil War,” says Thomas B. Allen, author of Harriet Tubman, Secret Agent. “But her recognition didn’t come till many years after the war.” (She didn’t receive her pension until 1899.)

The use of former slaves as spies was a covert operation—President Abraham Lincoln didn’t even tell the Secretary of War or the Secretary of Navy about it. The man in charge of the secret spy ring was Secretary of State William Seward, who’d met Tubman when his house was a stop on the Underground Railroad.

Tubman and other former slaves were effective as spies because white Confederates devalued their intelligence.

“They had lived their lives as invisible people,” writes Allen in his book. “That quality of invisibility, which Harriet Tubman knew so well, became the basis for using ex-slaves as spies for the Union.”

Venturing into Confederate territory, these spies would gather information from slaves about Confederate plans. Allen says, for instance, that slaves would tell spies where Confederate troops had dropped barrels filled with gunpowder into rivers to attack Union boats. Information gained from these spies became known as “black dispatches.”

It was brave for any ex-slave to venture into Confederate territory (these people were not legally “free”; they were still fugitives under the law). And it was especially brave for Tubman to do so, since she was well-known as an abolitionist.

“This was a woman with courage,” says Claire Small, former history professor at Salisbury University in Maryland. “And she wanted to be free, she wanted other people to be free. Otherwise she would not have risked her life.”

In his book, Allen tells the story of an eighty-one-year-old slave who ran toward Tubman’s boats when he saw them coming during her raid in 1863. For a moment, the man wondered if he was too old to leave with the soldiers.

But only for a moment.

He later recounted, writes Allen, that one was “‘Never too old for leave the land of bondage.’”

Follow Becky Little on Twitter.