The Viking age is welcoming a new kind of hero: women

New discoveries are breaking old assumptions about Viking women, rewriting history by restoring them to their rightful place on the battlefield.

It was on a sleepy Sunday morning in Stockholm’s central train station when I felt once again a familiar thrill—the jolt of being hauled out of the moment and transported to another, older world. I was in Scandinavia researching a story and having a coffee with an Uppsala University archaeologist, Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson. She had offered to show me Birka, the site of an early Viking town on an island west of Stockholm. As we passed the time before our ferry departed from a nearby quay, Hedenstierna-Jonson reached into her pack and pulled out a large copy of an engraving that had appeared in a 19th-century Swedish newspaper.

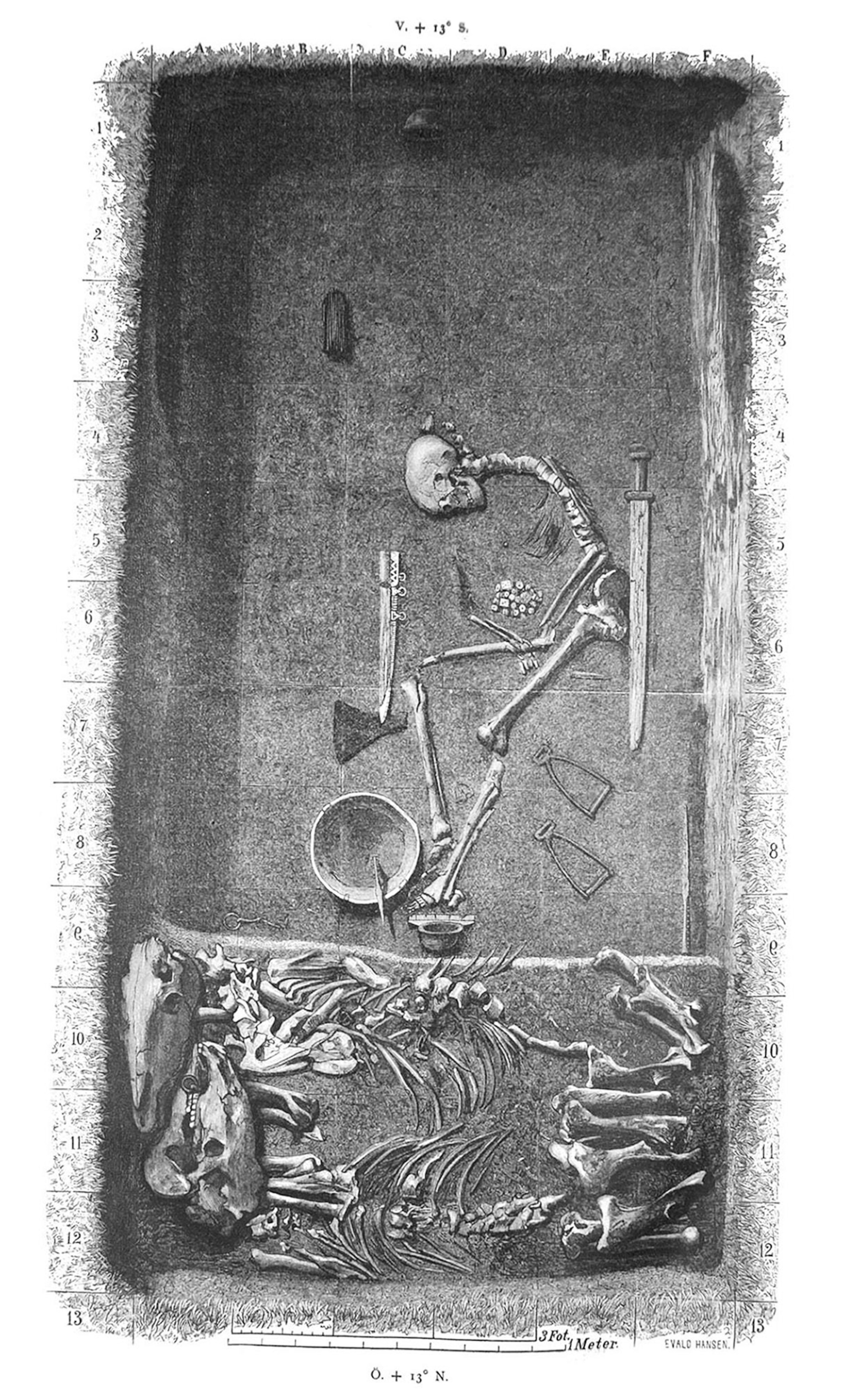

Unfolding it carefully, she placed it on a table and smoothed out the wrinkles. As I gazed down at the paper, I felt the solid walls of the train station slip away and the Viking age suddenly reach out to me. The engraving, rendered in almost photographic detail, portrayed a large underground Viking burial chamber containing skeletal remains and an arsenal of Viking weapons. In 1877, Hedenstierna-Jonson explained, a Swedish archaeologist named Hjalmar Stolpe had discovered the grave, now known as Bj 581, near a Viking military garrison in Birka.

I stared at the depiction of the grave. At the far end of the chamber, on a ledge, Stolpe and his team found not just one but two horse skeletons lying side by side. In the center, a human skeleton rested on its side, hinged forward at the hips as if the body had once been seated on something. Two iron stirrups lay nearby, as well as surviving bits of costly clothing and an ancient board game. Arranged around the skeleton, Stolpe found an arsenal: fragments of a sheathed sword, a broadax, a battle knife for hand-to-hand fighting, two spears, two shields, and more than two dozen arrows. Notably absent were items of jewelry that researchers had long associated with Viking women, including brooches.

Based on the contents of this spectacular grave, it was Stolpe’s conclusion that the occupant was a man—an important male warrior. This finding was widely accepted by other Scandinavian researchers, and as news of Stolpe’s discovery spread, Sweden’s Ny Illustrerad Tidning—New Illustrated Magazine published a remarkable engraving of the Birka Warrior’s burial, inspired by the archaeologist’s technical drawing. So detailed and compelling was this illustration that it was published and republished for decades in books on the Vikings. The burial “was unusually rich in grave goods, even by today’s standards,” Hedenstierna-Jonson says, “and it got a lot of attention.”

For nearly 140 years, Stolpe’s interpretation of the burial went unquestioned by archaeologists. Generations of Scandinavian researchers accepted the view that warfare was the exclusive business of men during the Viking age, a period that began around the mid-eighth century A.D. and gradually wound down in the mid-11th century. Medieval Scandinavian poets, after all, had vividly evoked the surreal horrors of Viking combat. In their nightmarish verses, a sword was “slaughter-fire” or “corpse gleam.” Spears were “blood snakes” or “the fires of Odin.” Battle itself was “weapon thunder,” “spear-storm,” and “army-reddening.” In all, Scandinavia’s early poets coined around 3,500 figures of speech to describe warfare and weaponry: a terrifying richness of language. Clearly, agreed scholars, the brutal realm of Viking combat was no place for a woman.

The Birka Warrior’s male identity stuck.

(These are some of the world’s most spectacular Viking artifacts.)

Birka and the entire Viking world are arguably getting even more attention today. With a host of new excavations across the North and the advent of advanced investigative techniques such as ancient DNA sequencing and isotopic analysis, archaeologists have been uncovering an increasingly complex picture of Viking life.

Evidence now shows, for example, that the Viking age began decades earlier than previously suspected, when heavily armed Viking warriors sailed to what is now Estonia around 750 and met violent deaths at the hands of their enemies. And over the next three centuries, Viking expeditions crossed at least eight seas, journeyed to some three dozen countries, and encountered more than 50 different cultures, from Canada’s east coast to the steep mountain passes of Afghanistan. No other Europeans of the day were so daring, so driven by curiosity and wanderlust.

In eastern Europe, Viking trading expeditions journeyed along the dangerous rivers of modern-day Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine, fending off attacks from mounted warriors on the Eurasian steppes to reach two of the richest cities in the world at the time: Constantinople (now Istanbul) and Baghdad. And by at least the early 11th century, intrepid parties of these Scandinavian seafarers landed on the coast of North America. On the northernmost tip of Newfoundland, researchers have discovered the remains of a Viking base camp inhabited in 1021—exactly 471 years before Christopher Columbus laid eyes on the Americas.

(Vikings in North America? Here's what we really know.)

Clearly, the Vikings had a remarkable talent for making history, but for decades many scholars focused on the men of the North, assuming they were the only seafarers, pillagers, and traders. But what about the Northwomen? What were they doing during that time? Archaeologists seldom paid as much attention to them, assuming that Viking women were primarily homebodies. “When you go into a museum,” says Marianne Moen, an archaeologist at the University of Oslo, “chances are you will find the women doing one of two things: holding babies or cooking.”

Was it really that simple and straightforward? Until recently, there were few clear answers. But as more Scandinavian women gravitated toward the field of archaeology in the late 20th century, some began examining the lives of the Northwomen from fresh perspectives. Today their analyses of new excavations and old museum collections are revealing many surprises and a larger female presence. Some Viking women wielded great influence in the North—as powerful queens, regents, seeresses, sorceresses, landowners, leaders of sacred cults, alliance-builders, traders, and travelers.

(The graves of ‘woman warriors’ are changing what we know about ancient gender roles.)

Beneath a huge earthen burial mound at Oseberg in Norway, for example, researchers in 1903 discovered a sleek Viking longship adorned with fine carvings. It is the most lavish Viking grave known to archaeologists. The ship brimmed with tapestries and other artworks and contained the remains of two high-status women, one of whom was likely a respected ritualist and powerful sorceress, judging from her grave goods. In the Viking world, sorceresses were said to possess many magical powers, from predicting the future and controlling the weather to performing “battle magic”—dark rituals to turn the tide of war. In Viking warfare, says Neil Price, an archaeologist at Uppsala University, “magic was as important to fighting as sharpening your sword.” Most of this magic was conducted by women.

Other women were skilled artisans who played a critical role in outfitting the famous Viking raiding and war fleets. They produced a high-quality wool cloth for the sails on Viking longships. It was an enormous task. Experimental archaeology conducted at the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, Denmark, for example, has revealed that producing just one sail for a large warship would have required at least 10,269 hours of labor (the equivalent of some 3.5 years, using a standard of eight-hour workdays, without any weekends off). In addition, women made all the high-quality woolen clothing worn by the crew of such a warship, and Danish textile expert Lise Bender Jørgensen has calculated that as much as 17.5 years of labor by a team of women was needed to clothe a crew of 70. Clearly, skilled female artisans were integral to the success of the Viking raids and other military campaigns abroad. But the involvement of women in Viking warfare did not end there.

(An intact Viking ship burial held riches—and a surprising mystery.)

Remarkable evidence now suggests that at least a few of the Northwomen were trained in combat as warriors. The revelations began just over a decade ago, in 2014, when Anna Kjellström, a biological and medical anthropologist at Stockholm University with a reputation for thorough research, started examining the remains of the famous Birka Warrior as part of an ongoing study on the health of the Vikings. During her scientific assessment of the individual in Bj 581, Kjellström determined that the warrior would have been roughly five feet seven inches tall—just slightly shorter than the average Viking male—and probably died between the ages of 30 and 40 years. But as the anthropologist began evaluating the sex of the skeleton, she discovered something intriguing: Several key anatomical indicators didn’t fit the profile of a male.

The width of the greater sciatic notch on the warrior’s pelvis, for example, was considerably broader than the mean value for males; it resembled that of females. Moreover, the warrior’s pelvis possessed a wide groove known as the preauricular sulcus, usually a female characteristic. And the warrior’s chin was small and pointed—another female trait. Indeed, “several features of the skeleton,” Kjellström explained to me later via email, “were feminine.” Puzzled, she asked two other anthropologists to evaluate the sex of the skeleton independently. Both came to the same conclusion. The famous Viking warrior at Birka seemed to be a woman.

(Viking ship's buried clues may reveal identities of mystery women.)

The Old Norse sagas contained intriguing stories of warrior women. Danish scholar Saxo Grammaticus included several of these legendary female figures in his book Gesta Danorum—Story of the Danes, completed in the early 1200s. One of the most famous was Ladgerda, who married a Viking warlord. According to Saxo Grammaticus, she was an accomplished warrior who refused to dress as a man in battle. Indeed, she fought with her hair unbound and streaming down her back. But most 20th-century archaeologists dismissed such stories out of hand as the inventions of medieval storytellers. They believed Viking women spent their days as traditional homemakers—preparing food, cooking, making clothes, and caring for children.

Hedenstierna-Jonson wasn’t so sure. She had conducted extensive research at Birka and knew that the garrison hall there had once bristled with iron weapons and that it rested upon offerings of iron spearheads. It was a profoundly martial place: one dedicated to the Spear-Lord himself, Odin. The decision to bury an individual so close to the Viking garrison and its sacred ground was in itself a mark of high esteem—one likely awarded to a distinguished military figure. Could a woman warrior have been buried in that prestigious grave?

As luck would have it, Hedenstierna-Jonson and Kjellström had received generous funding to conduct a large DNA study of prehistoric human remains in Sweden. The well-preserved Birka Warrior skeleton was a prime candidate for the project. So in 2015, scientists at Stockholm University proceeded to take two tiny samples—one from the individual’s canine tooth, the other from an upper arm bone—and successfully extracted ancient DNA from both. With this, geneticists generated genomewide data to identify both the sex and the ancestry of the fighter on a molecular level.

Hedenstierna-Jonson had received the results from these tests not long before we met at the train station in Stockholm. The individual in the famous warrior grave, she told me, had genetic affinities to the modern inhabitants of southern Sweden. But the most fascinating result came from the DNA analysis of the warrior’s biological sex.

The individual in Bj 581, Hedenstierna-Jonson announced, “is a woman.”

This line of scientific research soon got more complicated, however. In 2017, Hedenstierna-Jonson and nine of her colleagues published their DNA study on the Birka woman in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology. To their surprise, the eight-page report, which was peppered with phrases like “epiphyseal union” and “nucleotide positions,” set off a firestorm.

While some Viking specialists were impressed by the research, others took strong issue with it. Some critics suggested, for example, that the Birka grave may have originally contained both a male warrior and a female companion and that the skeleton of the male was removed at some point. But there was no evidence at all to show that a second body was ever interred in the grave.

Other researchers raised a more theoretical objection. The dead, they noted, did not bury themselves. Mourners, they suggested, could well have placed a trove of costly weapons belonging to the dead woman’s father or husband in the grave as symbols of the woman’s high status. But other evidence clearly indicated that the weapons were hers. Some old Scandinavian poems, for example, explicitly described the practice of mourners burying dead warriors with their weapons. Besides, no one had suggested that all the weapons in the Birka grave were merely family heirlooms when the skeleton was thought to be male, so why bring up that idea now?

Stunned by the reaction, Hedenstierna-Jonson and several other researchers decided to expand their investigation of the famous grave. Some team members pored over historical records for even brief mentions of Viking warrior women. Perhaps the most intriguing reference came from the 12th-century text Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaibh—The War of the Irish With the Foreigners. In it, an Irish writer recorded the names of 16 Viking commanders who led attacks on the region of Munster in the mid-900s. Among these military leaders was a Viking woman, Inghen Ruiadh’, whose name means “Red Girl” or “Red Daughter.” (The name may have come from the color of her hair.) She was clearly an important figure. “She’s a Viking, she’s a captain of a ship, and she’s the commander of a fleet,” Uppsala University archaeologist Neil Price, a member of the team, told me.

('100-year find’: Enormous Viking ship holds surprising clues on burial rituals.)

Hedenstierna-Jonson and her colleagues took a closer look at the goods in the famous Birka burial. What was particularly striking was the equestrian character of the grave. Although the Vikings are best known for their seafaring abilities, prosperous families in the North bred horses for riding and for work on their farms. The Birka woman likely came from just such a privileged background, and several clues pointed to her equestrian abilities. The hinged position of her skeleton suggested that she had been buried in a seated position—possibly on a saddle, whose wood and padding had rotted away, leaving only the iron stirrups found by her feet. Moreover, one of the horse skeletons on the ledge was bridled, as if ready to be ridden. In addition, the grave contained other equestrian gear, including what was likely a large currycomb.

The battle gear arranged around the warrior’s skeleton also told a story. The arrows, for example, were specially designed to pierce an enemy’s armor—these were not for show. The other weaponry in the grave—shields, spears, double-edged sword, broadax, and battle-knife—suggested that the warrior woman was also highly trained in several forms of attack, including hand-to-hand combat.

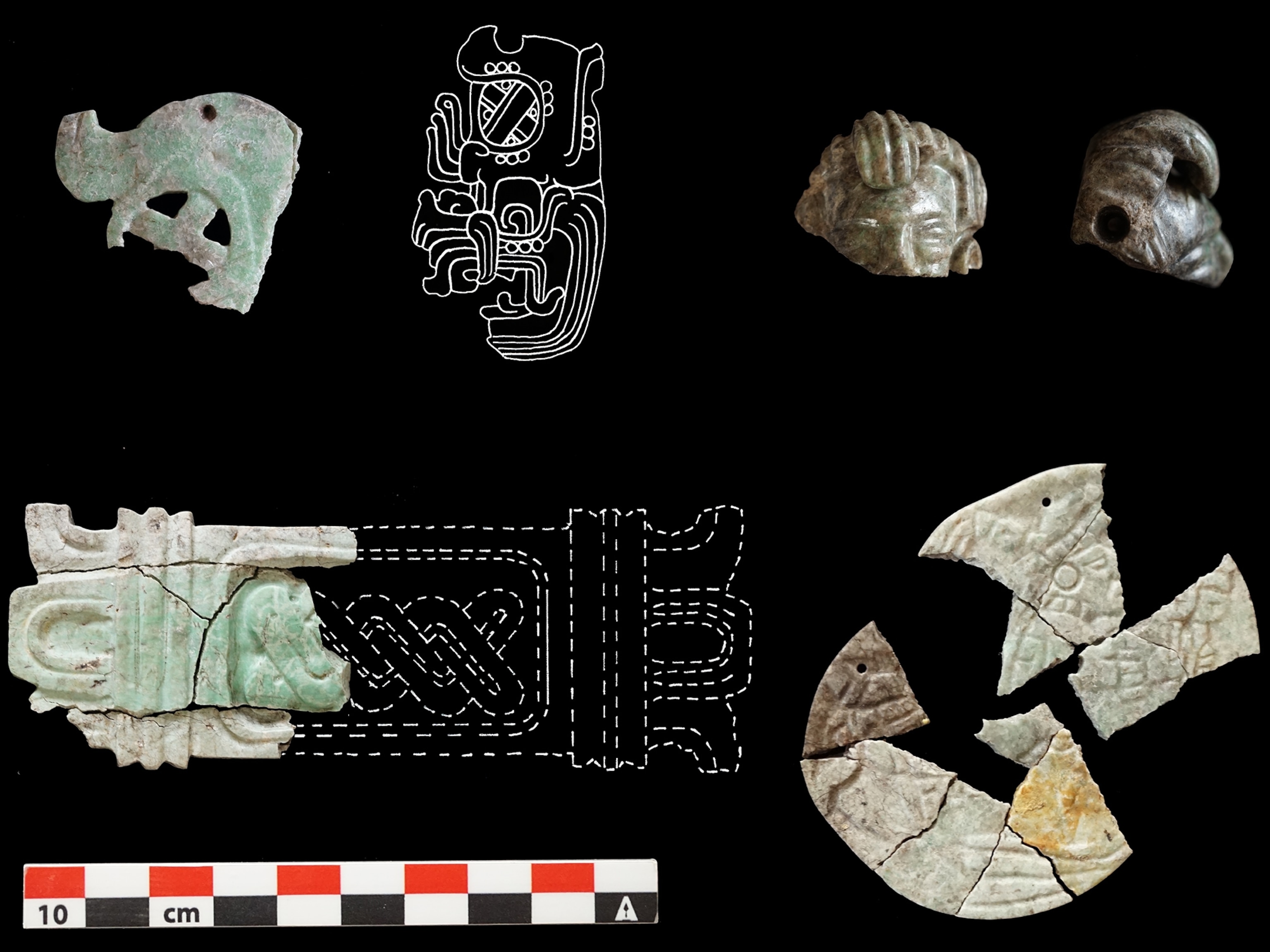

Other clues, including part of a silver coin minted by the Abbasid Caliphate, a sprawling Muslim empire whose capital lay in what is now Baghdad, linked the woman to the lucrative Viking trade in the East. And an analysis of the clothing fragments discovered in the grave revealed a distinctively Eastern style of dress. She was buried in a spectacular Eurasian-steppe style of riding coat, trimmed with silk and possibly ornamented with small pieces of mirror glass to catch the light. She also wore a costly silk cap decorated with a silver tassel and four small silver balls. Both the style and the materials inferred that it was likely manufactured in the Viking settlement of Kyiv, which was perched along a major river route leading to Constantinople.

Taken together, the clothing pointed to a very important person with strong connections to the East. Indeed, comparative research by Scandinavian archaeologist and textile specialist Inga Hägg suggested that individuals buried in such distinctive hats were likely cavalry commanders who reported directly to a king or prince—a theory the researcher proposed before the occupant of the famous grave was identified as a woman.

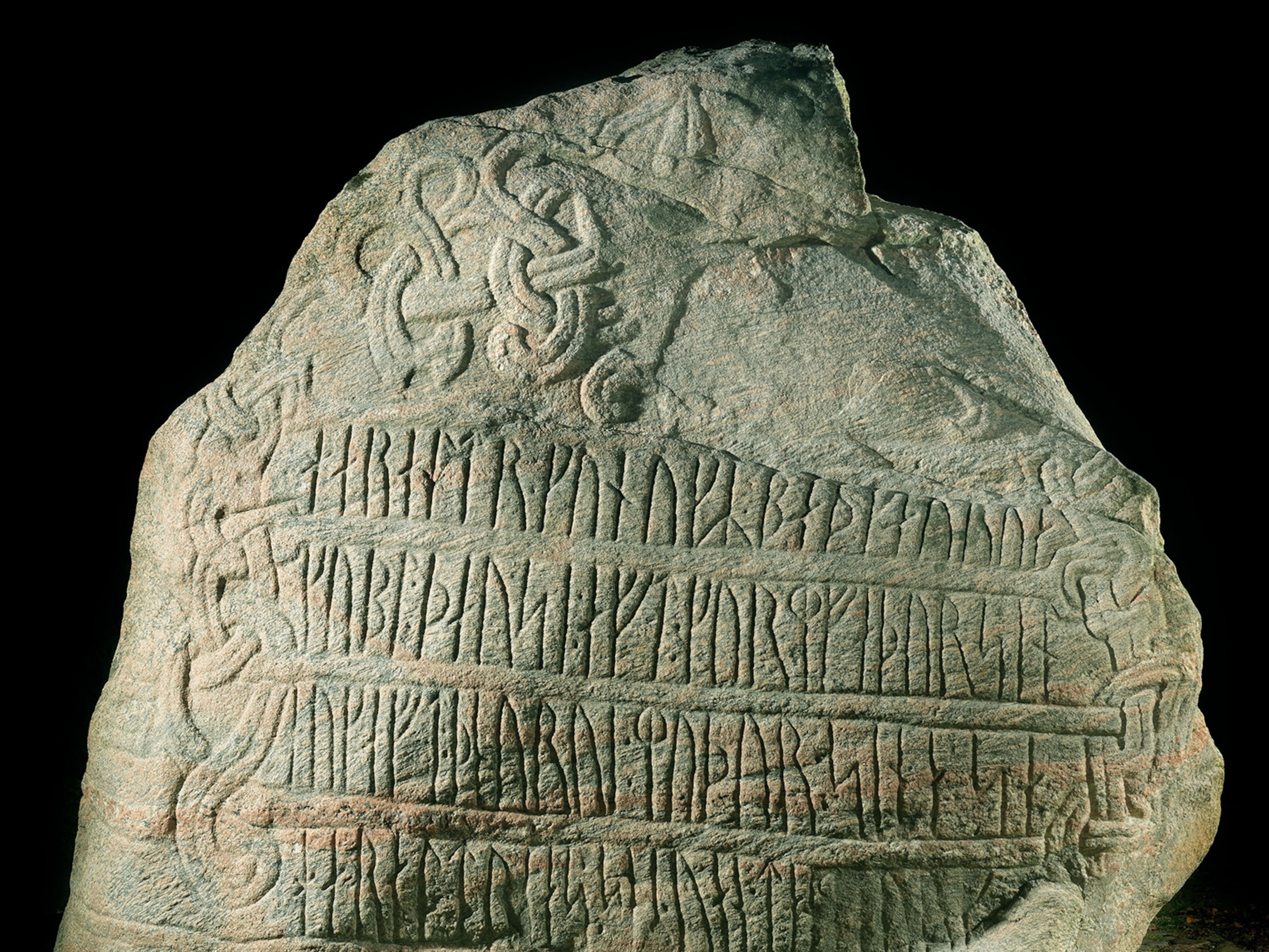

('Denmark’s salvation'? Runestones hint at Viking queen's power.)

Birka’s female warrior may have been skilled in a particular kind of equestrian combat. During the extensive excavations conducted at Birka’s garrison during the late 1990s and early 2000s, archaeologists found remnants of Eastern archery equipment, including arrowheads used with composite Eastern bows. The discoveries strongly indicated that some warriors garrisoned in Birka were trained in a type of horseback archery mastered by nomadic tribes on the Eurasian steppes. Today Hedenstierna-Jonson thinks the Birka woman may have trained as an Eastern horseback archer too. It’s “a suggestion rather than a fact,” she explained by email, adding that “it is based on the array of weapons in combination with the horses and the general [E]astern (i.e. Rus’ & steppe nomadic) feel to the grave and dress.”

The idea that the female buried in the famous warrior grave could have fought as a horseback archer was deeply intriguing. And I found myself wondering whether that ancient martial technique may have leveled the playing field for some female warriors in the Viking age. To learn more, I decided to reach out to a German scientist I knew who had undergone years of training to become a horseback archer herself.

Angela Graefen is an ancient DNA specialist in Germany who has studied and published on the genome of Ötzi, the well-known Iceman who was discovered melting out of a glacier in 1991. She wasn’t surprised by the suggestion that the Birka woman trained as a mounted archer. Indeed, the idea seemed plausible to her.

(Ötzi the Iceman: What we know 3 decades after his discovery.)

“Equestrian disciplines are the one Olympic field where men and women compete against each other on equal terms,” Graefen told me in an email. “While not an Olympic sport, the same applies to horseback archery, with several women among the ranks of the world’s best.”

Graefen also mentioned published archaeological evidence pointing to a long tradition of female horseback archers on the Eurasian steppes, an area well known to Viking traders and warriors. Excavations from as far west as Ukraine and as far east as Central Asia have uncovered the remains of approximately 300 armed females, some with horses and equestrian equipment, in burial mounds dating to between the eighth century B.C. and the fourth century A.D. In one remarkable grave field known as Mamaj Gora, in Ukraine, archaeologist Elena Fialko of the National Academy of Science in Ukraine discovered the burials of about a dozen women who “formed light-armed cavalry.”

The gear interred with these armed Eastern women varied widely, from swords and spears to armor and helmets. But the bow and arrow appeared to be the weapons of choice. Indeed, one ancient burial of a steppe woman along the Dnieper River contained a quiver holding 92 arrows. In the view of Adrienne Mayor, a Stanford University historian and an expert on the archaeological evidence of warrior women in antiquity, the combination of an equestrian lifestyle with archery created something powerful for women. “The horse and the bow were the equalizers. Women could be just as tough, fast, and deadly as men,” Mayor wrote in the journal Foreign Affairs.

In 2019, the Swedish team published a second article on the Birka woman in the journal Antiquity. They laid out pages of detailed archaeological and historical evidence to support the contention that the woman in the weapon-packed grave was a warrior and quite possibly a military commander. For many Viking age specialists, including Marianne Moen, the head of the department of archaeology at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo, this second paper was “very convincing.”

(Facts vs. fiction: How the real Vikings compared to the brutal warriors of lore.)

By the time Hedenstierna-Jonson and I reached Birka, it was well past midday and the sky had clouded over. We walked up the slope to the hill fort and the garrison hall, where Birka’s warriors once feasted and drank on long, dark winter nights. Hedenstierna-Jonson then turned and led the way to the burial ground that had once held the famous warrior woman.

On a high terrace, the researcher pointed to the spot where mourners had lowered the body into a magnificent, weapon-filled grave. I had hoped to see some kind of marker or sign of distinction, but there was nothing at all—no mound, no memorial, no grand vista, no outline even of the excavated grave. A dense thicket of green shrubs had taken root on the spot, shrouding the tomb in branches and leaves.

As we lingered there for a few minutes, the engraving of the burial chamber I had seen earlier in the day flashed through my mind—the human skeleton resting on the ground, the weapons of a professional warrior carefully arranged all around the bones. For nearly 140 years, that image had captivated archaeologists and others, raising a myriad of questions about the tomb and the identity of its occupant.

Now, thanks to the work of a modern interdisciplinary team of scientists, we have a fuller picture with evidence showing that this individual was a woman, a female warrior whose distinguished life ended in a grave of an important military figure. She had not just endured the spear-storms and weapon thunder of Viking battlefields, it seemed, but she’d also excelled there, inspiring the loyalty of those who fought with her. And as I think about what we have now learned, I am overcome with respect for her.

Today nature has reclaimed her grave, but Birka’s woman warrior no longer languishes in obscurity. She is once again part of human memory, taking her rightful place in the great drama of the Viking age.

(The Viking origins of your Bluetooth devices.)

Heather Pringle, a British Columbia–based writer, has been covering the ancient world for over four decades. She is the author of The Northwomen: Untold Stories From the Other Half of the Viking World, published by National Geographic Books, from which this article was adapted.

For this story, Nora Lorek, a Sweden-based photographer, dressed in period costume with Viking reenactors in Denmark, learned how to shoot arrows, and dived deep into Scandinavian archives.