Why we sing ‘Auld Lang Syne’ on New Year’s Eve

The iconic song became a staple at the stroke of midnight with a little help from 18th century poet Robert Burns and the Scottish diaspora.

If New Year’s Eve had an official carol, it would easily be “Auld Lang Syne.” Every year, just after the clock strikes midnight, people around the world join hands and sing this beloved song.

Why is “Auld Lang Syne” a New Year’s tradition? From its beginnings as an 18th-century Scottish poem to its iconic status today, “Auld Lang Syne” captures the spirit of the holiday.

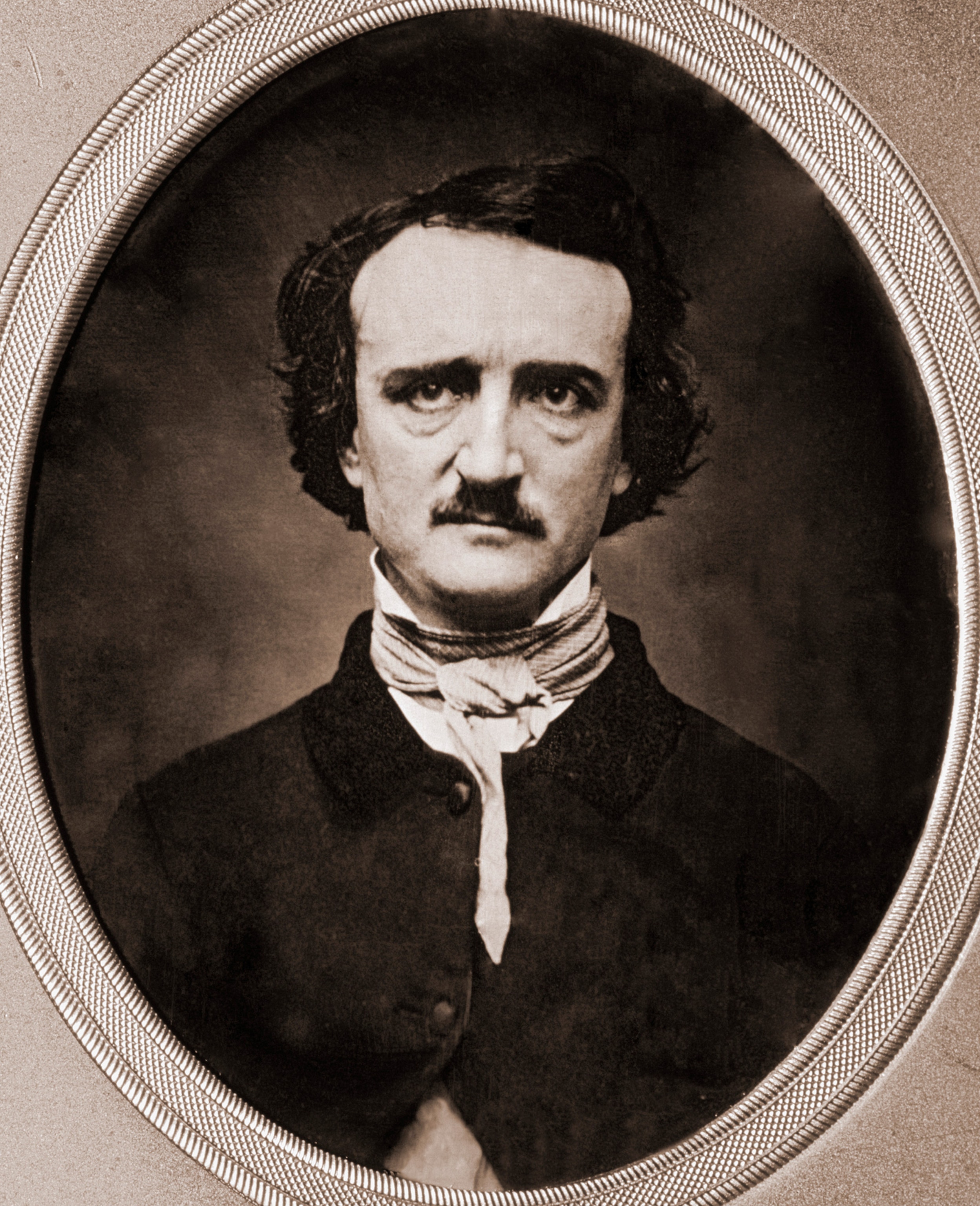

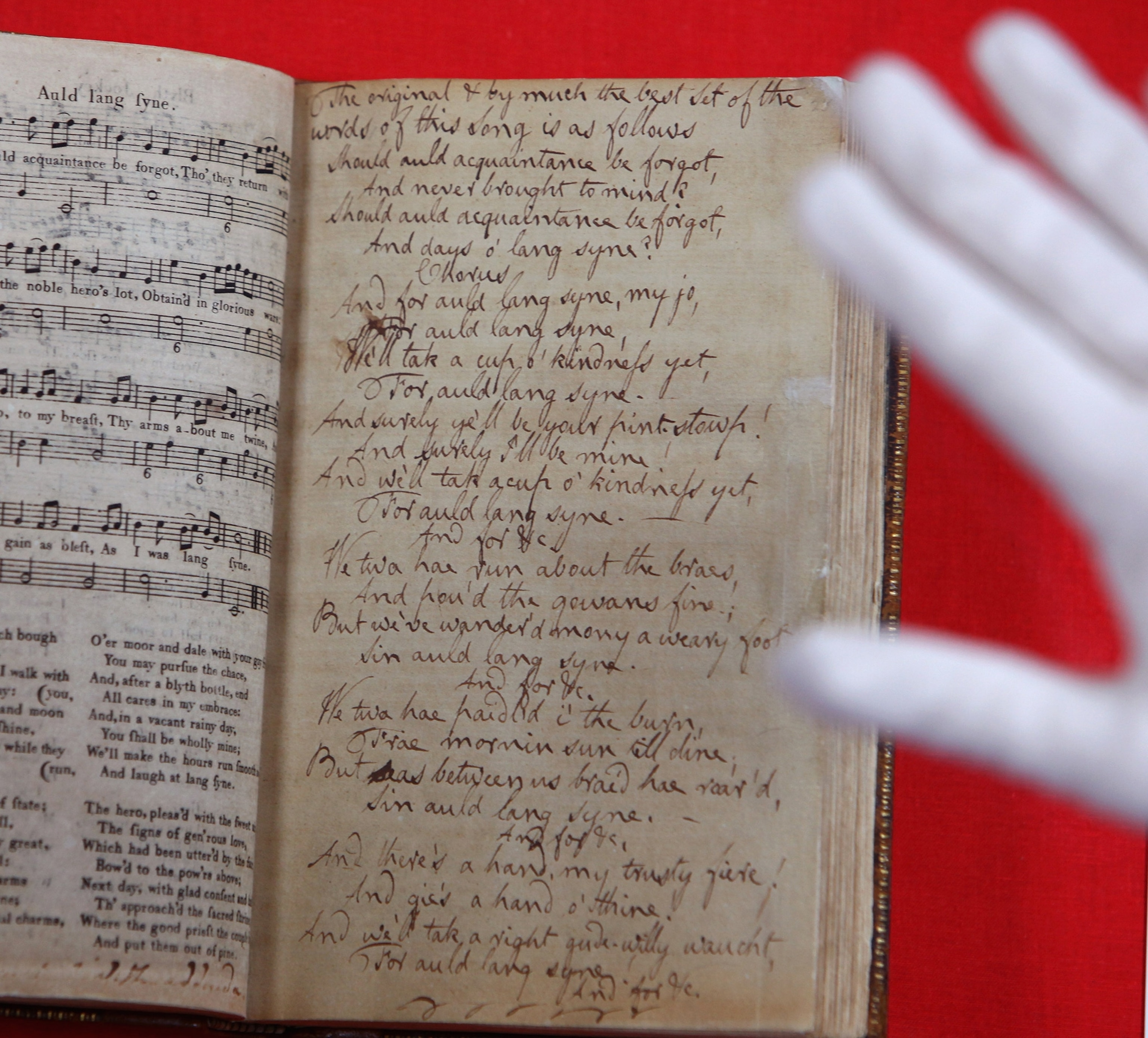

A Scottish poem

The song is actually a poem penned by Robert Burns in 1788. Traditionally considered Scotland’s national poet, Burns stirred the country’s national consciousness by writing in the dying out Scots language. In English, auld lang syne roughly means “times long past.” Fittingly, the song tells of old friends meeting after time apart.

Although Burns’ version is the one that we know today, there were earlier versions of the poem, including Allan Ramsay’s from 1724. Burns explained his version was indeed inspired by another. As he claimed to music publisher George Thomson in September 1793, “I took it down from an old man’s singing.”

Burns was not satisfied with his version of the poem’s original tune, dismissing it as “mediocre.” So between 1799 and 1801, Thomson found and fine-tuned a different melody for the song. It’s the one we still sing today.

A song for the year’s end

Burns’ song soon found a home in an annual Scottish tradition: Hogmanay. A blend of Norse and Gaelic customs, the holiday celebrates the last day of the year.

For centuries, Hogmanay, not Christmas, reigned as the biggest winter holiday in Scotland. After all, the Church of Scotland, the country’s official church, had banned the celebration of Christmas in 1640, since it felt the holiday was not Protestant enough.

(Christmas was also banned in 17th-century England—and it didn’t go over well.)

Unable to make merry at Christmastime, people embraced Hogmanay instead. During Hogmanay, Scottish men, women, and children exchanged gifts and visited friends and neighbors to welcome the new year.

Another Hogmanay tradition? Singing. Some songs—such as “A Guid New Year to ane a’ A’”—were widely recognized. Others were created by families or local communities.

With its emphasis on friendship, reminiscence, and parting, Burns’ “Auld Lang Syne” expressed the essence of Hogmanay: bidding adieu to one year so another could begin.

A New Year’s tradition

As Scotspeople emigrated in the 19th century, they brought their Hogmanay traditions with them around the world—including “Auld Lang Syne.”

The song soon became a fixture in New Year’s Eve celebrations in the United States. Jazz band Guy Lombardo and His Royal Canadians played it during a New Year’s Eve radio broadcast in 1929. It was a hit—and “Auld Lang Syne” remained a midnight staple of the band’s annual New Year’s Eve show, which aired on radio and eventually television every year until 1976. The show’s success popularized “Auld Lang Syne” as the quintessential New Year’s song across the country.

(The new year once started in March—here's why.)

As Life reported on December 17, 1965, “Should [Lombardo] and his Royal Canadians fail to play ‘Auld Lang Syne’ at midnight on New Year’s Eve […], a deep uneasiness would run through a large segment of the American populace—a conviction that, despite the evidence on every calendar, the new year had not really arrived.”

However, musicologist M.J. Grant emphasizes in her book Auld Lang Syne: A Song and Its Culture that at the time the song “was already firmly established in many communities, quite possibly beginning in the Scottish diaspora.”

So the tradition of playing “Auld Lang Syne” on New Year’s may have not started with Lombardo, but his band ushered in a new beginning for a song that honors the past while welcoming the dawn of a new day.