Color and magic fill Bali’s skies with the return of a beloved kite festival

The mesmerizing sight brings back a long-cherished tradition—and an uptick in tourism

When the winds begin to pick up over the Indonesian island of Bali in late May, the skies are streaked with fluttering colors—the reds, yellows, and blacks that announce the arrival of kite season.

It’s a summer pastime that evokes joyful memories of childhood for Balinese photographer Putu Sayoga. As a young boy, he’d watch older kids pull kites through rice fields near his village of Tunjuk after harvest season. Sometimes they’d let Sayoga tie the string onto the kite, and he’d look on with envy as it danced through the sky. He tried to make his own kite, but struggled to shape bamboo sticks to hold the colorful paper. An older boy who learned kite making from his father and uncle helped Sayoga and his friends, crafting them a fish-shaped bebean kite, considered the easiest to fly.

When the wind didn’t come—and it rarely blew through the fields as powerfully as it did on the beaches—the boys would whistle loudly, acting out stories of Rare Angon, the Hindu god revered by kite flyers. According to lore, his magical flute beckoned the wind. Kites that dance on those gusts are said to help farmers keep pests away from their harvests.

There wasn’t much else to do in the long summer afternoons when he was a child in the early 1990s. “There were no mobile phones at that time,” he says, laughing.

In the 1970s, foreign visitors began coming in droves to Bali’s white sand beaches and in 1978 the island launched an annual kite festival on the popular beaches of Padang Galak and Mertasari that quickly grew into a large competition. Dozens of teams from nearby villages, along with visitors who learn to build and fly kites in the Balinese style, strive to be the top flyers on the island.

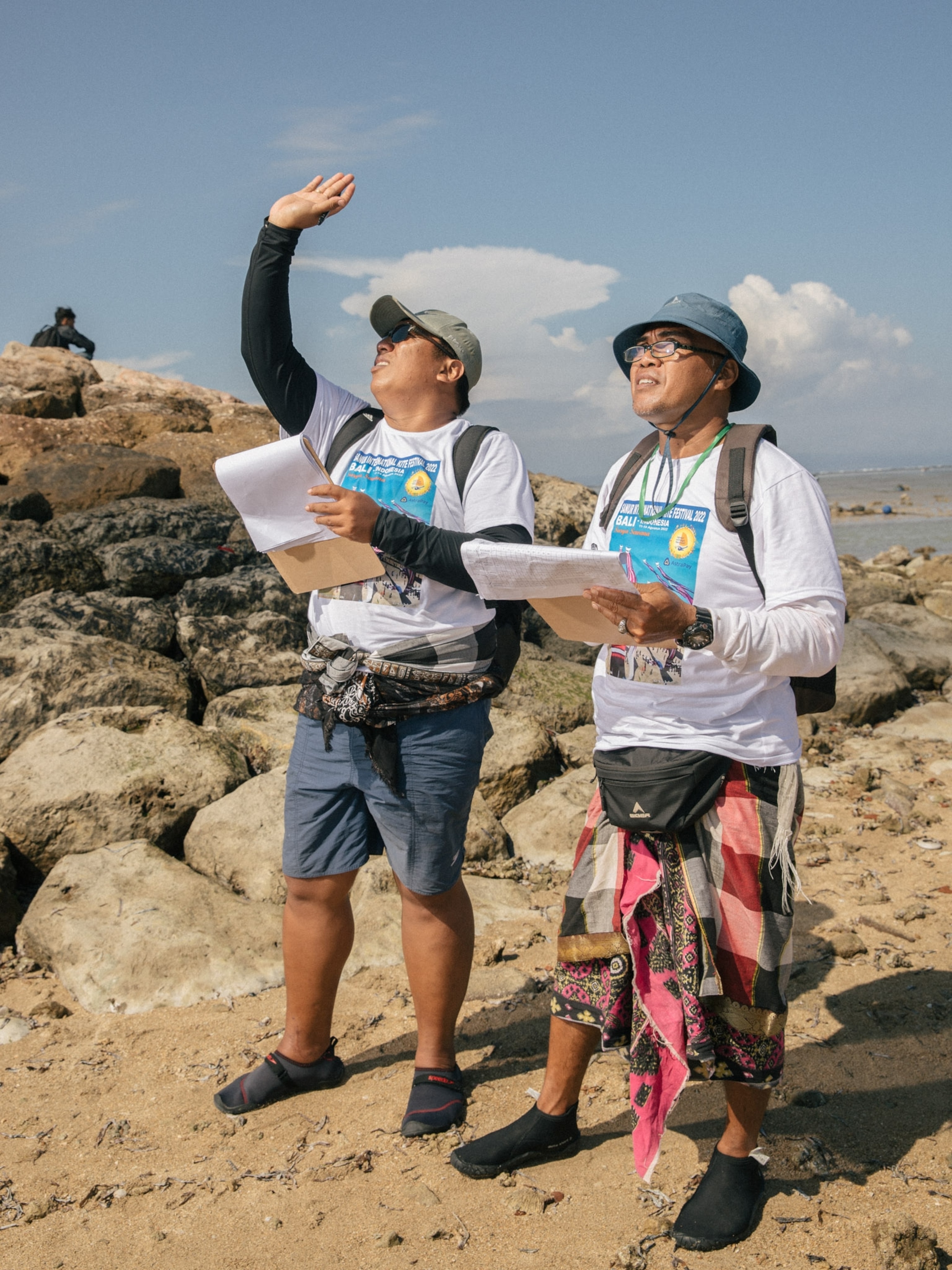

Four styles of kite take flight at the festival: the ornate, long-tailed bird or dragon; the fish, perhaps the most popular; and the leaf, considered the toughest to fly because of its curved shape. A fourth type of kite is left open to interpretation, and participants can adapt Balinese culture and history for the skies. Judges score each team on the kite’s aesthetics, its ngonyah—how smoothly it moves with the wind, and how gently it lands.

The COVID-19 pandemic put the festival on hold. Bali’s six million annual foreign visitors disappeared, and the economy crashed. But in the absence of tourists, Sayoga rediscovered the beauty of impromptu kite flying. Kites were a cheap outdoor activity, and last year, he began photographing the pastime.

One day, Sayoga spotted a colorful soiree overhead. Down a small side road, he found an illicit festival. The police had ejected the kite fliers from the beach, so they’d relocated to a discreet rice paddy. Sayoga asked if he could document it and they agreed—so long as he aimed his lens on the kites and not their faces.

This year, the official kite festival has returned to Bali’s beaches, but informal festivals, like the one Sayoga photographed, have also stuck around. For Sayoga, who had long avoided the overcrowded pre-pandemic festivals, these intimate gatherings have helped him rediscover the entertainment he loved as a child: watching his friends and neighbors take advantage of the winds. Now when he goes to see the kites fly, he may deliberately leave his camera at home.

“Last week I visited a small festival,” he says. “And I went just for fun.”