For ancient Egyptians, dance was a huge part of daily life

Several tombs in the necropolises of Egypt depict figures dancing across the walls and playing instruments. But when Egyptologists took a closer look, they were able to piece together how the art form evolved.

From easing the passage of the deceased into the afterlife to celebrating the joys of life on Earth, dance was integral to the daily lives of ancient Egyptians. Depictions of dancers on tombs and in temples dating across two millennia helped Egyptologists piece together the rituals surrounding Egyptian dance and how dancing evolved through time.

In its early stages, formal dancing was performed by priests and ritual performers to celebrate gods at religious festivals or processions. Later, dance was used in a variety of more secular settings, such as performances to entertain guests at banquets. Throughout its long history, the repertoire of Egyptian dance was enriched by new styles and moves.

(Do you have poor posture at work? So did the ancient Egyptians.)

A ritual performance

Conventions governing ritual dance developed after Egypt’s unification around 3100 B.C., when Egypt’s first dynasties fused Upper and Lower Egypt. This union led to the establishment of the Old Kingdom (ca 2575-2150 B.C.), a period of political stability that saw great advances in art and architecture, including the building of the Giza Pyramids. Depictions of dance at this time come from tomb scenes, mostly showing female dancers and musicians performing at a funeral procession or grave site.

(This ancient diary reveals how Egyptians built the Great Pyramid.)

These highly organized groups of professional dancers and musicians, known as khener, were affiliated with specific temples or funerary settings, led by a director, and performed mainly in ceremonies such as funerals.

The rhythm of castanets and tambourines

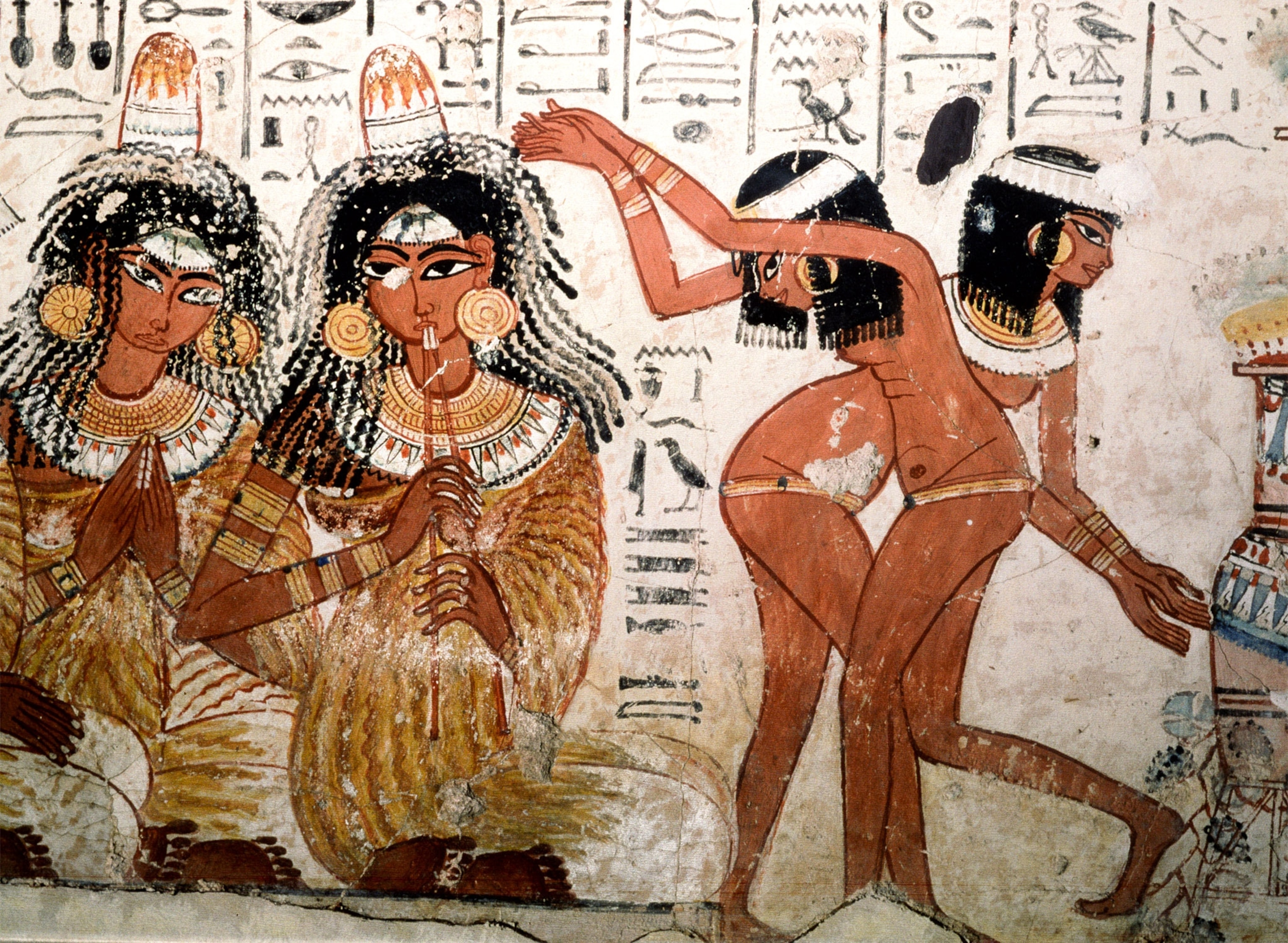

In this depiction of a funeral procession during the New Kingdom, the left side shows a group of female dancers of different ages beating tambourine-like

fragment of a funerary relief instruments. Next to them, two younger dancers play castanet-like instruments as they dance. To the right, two soldiers, three priests, and (at the edge of the fragment reproduced here) three dignitaries raise their arms in jubilation. The limestone relief, which dates to the 19th dynasty, circa 1250 B.C., is now in the Egyptian Museum.

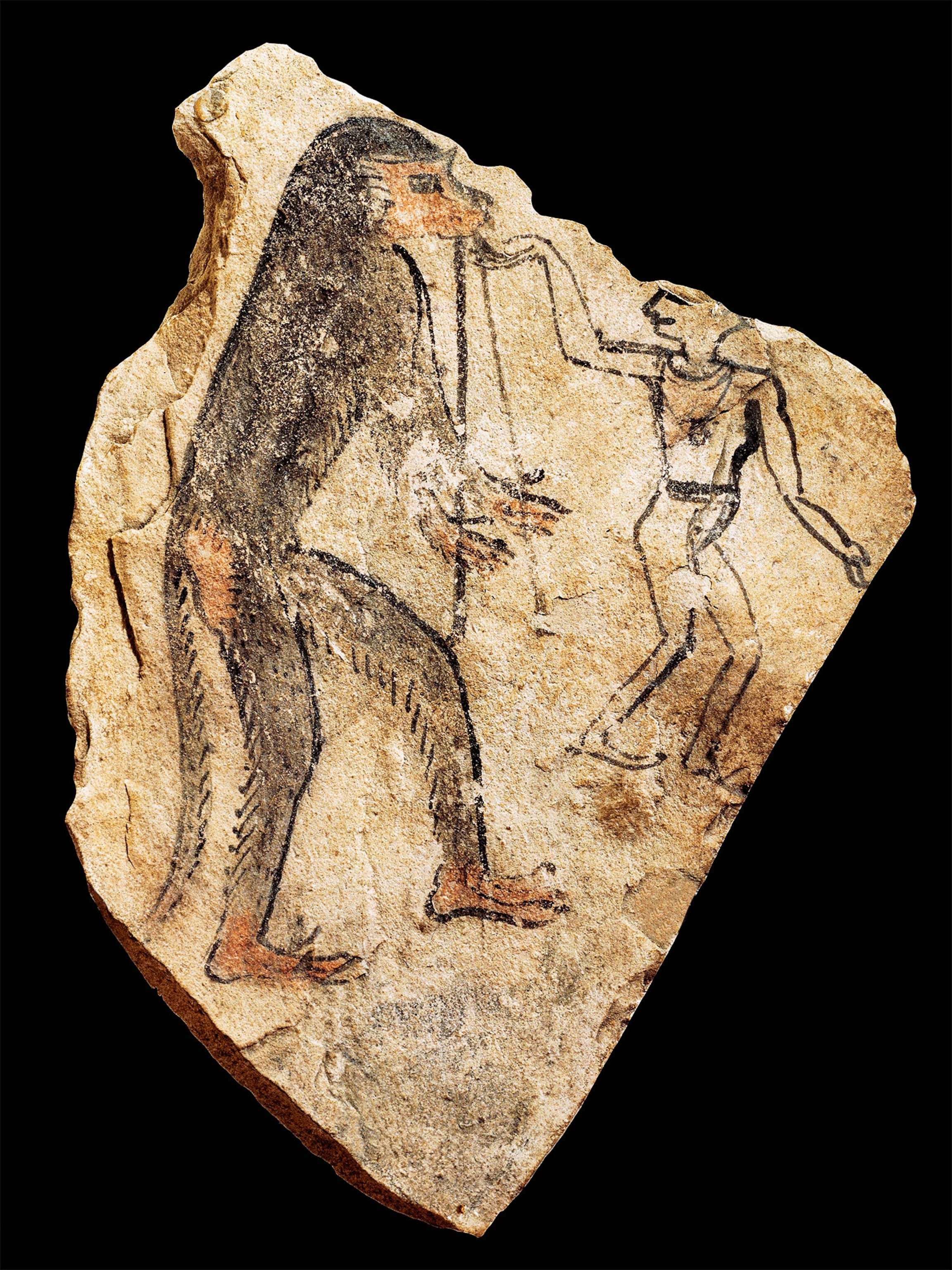

As a rule, early ancient Egyptian art depicts mostly female dancers, but there are exceptions. A well-preserved depiction from the third millennium B.C. comes from the early 2nd-dynasty tomb of Nynetjer at Giza, prior to the start of the Old Kingdom. It shows male dancers holding throw sticks used to hunt birds, accompanied by female musicians and followed by a female dwarf. Dwarfs were often depicted participating in dances, as they were associated with Bes, god of music and childbirth, who was represented as a dwarf and frequently shown dancing.

Tomb art often shows the dancers accompanied by Egyptian instruments. One notable instrument was the sistrum, which was made of bars loaded with small metal disks and played like a kind of rattle. The sistrum was often used in dances dedicated to Hathor, goddess of joy, love, music, and beauty.

At funeral ceremonies, Hathor, who was believed to have power over fertility, was invoked to bring about the rebirth and revival of the deceased in the afterlife. Female dancers waved sistrums to evoke the noise Hathor made as she walked through the reed beds. The rattling sounds they produced were thought to be pleasing to the divinities.

Dancing monkeys

The association of Hathor with dance would persist throughout Egyptian history. The Temple of Hathor at Dendera, a structure dating from the Ptolemaic period (332-30 B.C.), bears the following inscription:

We beat the drum to her spirit, we dance to her Grace. We raise her image up to the heavenly skies. She is the lady of the sistrum, the mistress of jingling necklaces.

(Worship of this Egyptian goddess spread from Egypt to England.)

A joyful turn

A time of turbulence and weakened central rule known as the First Intermediate Period followed the Old Kingdom. After that, the Middle Kingdom (ca 1975-1640 B.C.) was characterized by a flourishing of the arts under renewed central government.

In this period, the structured nature of ritual dance performances, which had been confined to the sanctity of the temples and only seen by a select group of priests, changed. Dances were brought into the open for processions held at public rituals, such as when a divine image was taken from its temple and paraded to visit other deities at their temples. The public was able to join in, and dancing became less inhibited. In a far leap from its solemn beginnings, dancing turned into a joyous, lively act.

Honoring gods and the pharaoh

The Story of Sinuhe, one of the oldest Egyptian literary texts recovered from the Middle Kingdom, includes passages that are testaments to the joyful turn that dance took. The tale recounts how an Egyptian man fled his kingdom and lived as a foreigner for some time but became desperate to return to Egypt. When the king welcomed Sinuhe back and agreed to allow him to be buried in Egypt, Sinuhe spontaneously broke into a dance of joy: “I roved round my camp, shouting and singing.” His town, too, was “in a festive mood, my young people rejoicing with dance.”

Dance scenes created during the Middle Kingdom show increasingly sophisticated acrobatic routines. Dancers are portrayed lying on their stomachs and reaching back until their hands touch their feet, and male dancers, by then depicted more frequently, are shown doing pirouettes.

(Archaeologists had to remove two millennia of grime to reveal this ancient Egyptian artwork.)

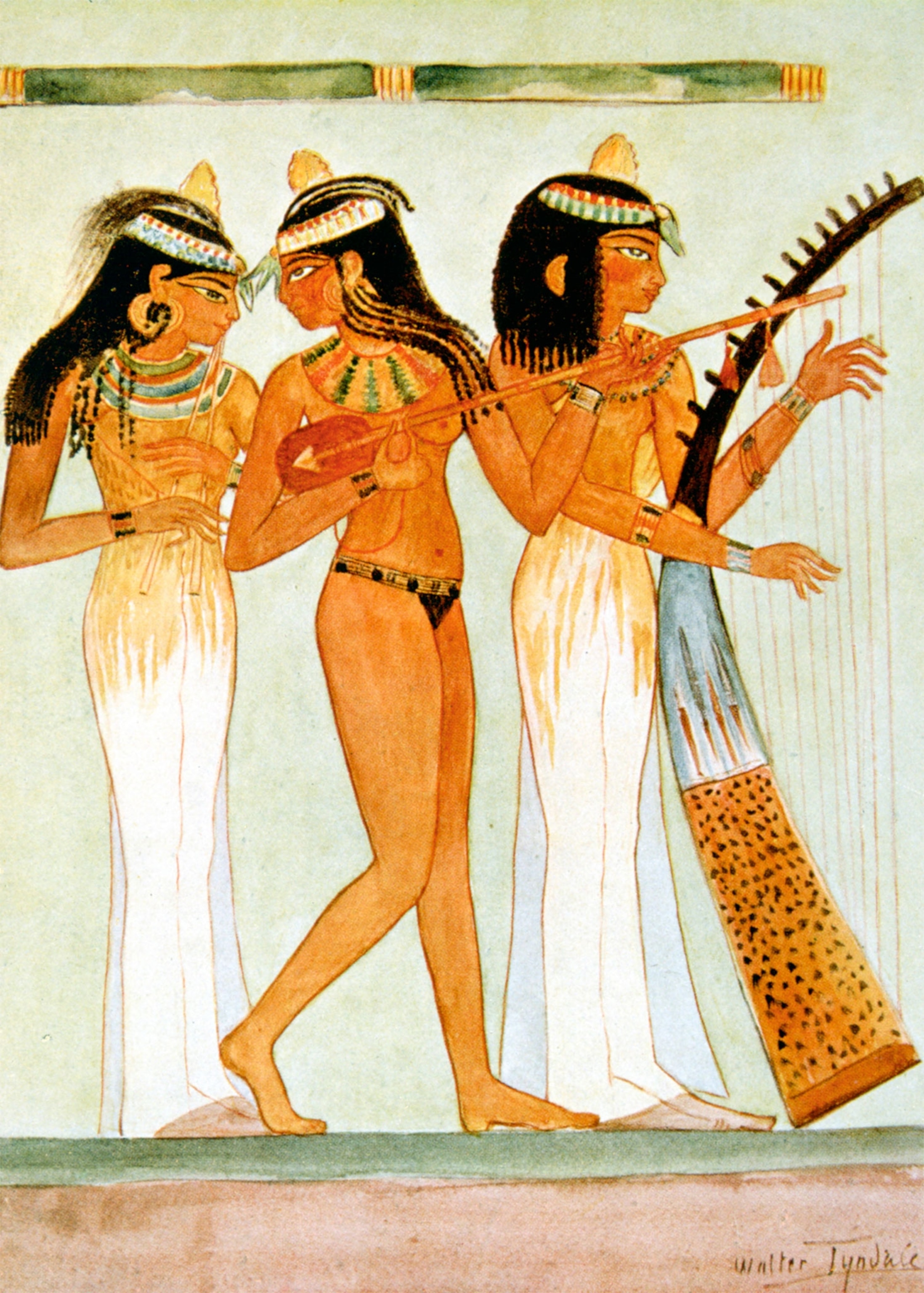

During the New Kingdom (ca 1539-1075 B.C.), when ancient Egypt reached the zenith of its regional power, the appearance of dancers transformed. They swapped skirts or dresses for scarves or bands around their hips, let their hair loose, wore sophisticated jewelry, such as anklets, and outlined their eyes with a large quantity of kohl.

The music evolved as well. A greater variety of stringed instruments accompanied dancers, which is thought to have influenced the movements. Nubian dancers, from the region south of Egypt, also brought their own steps into the dance.

Even as it evolved, dance remained an important part of religious rituals. Tomb art in the New Kingdom depicts the male funerary dancers known as the muu. With their vegetable fiber headdresses reminiscent of the pharaonic crown of Upper Egypt, they represented incarnations of the gods of the necropolis who helped transport the deceased to the afterlife.

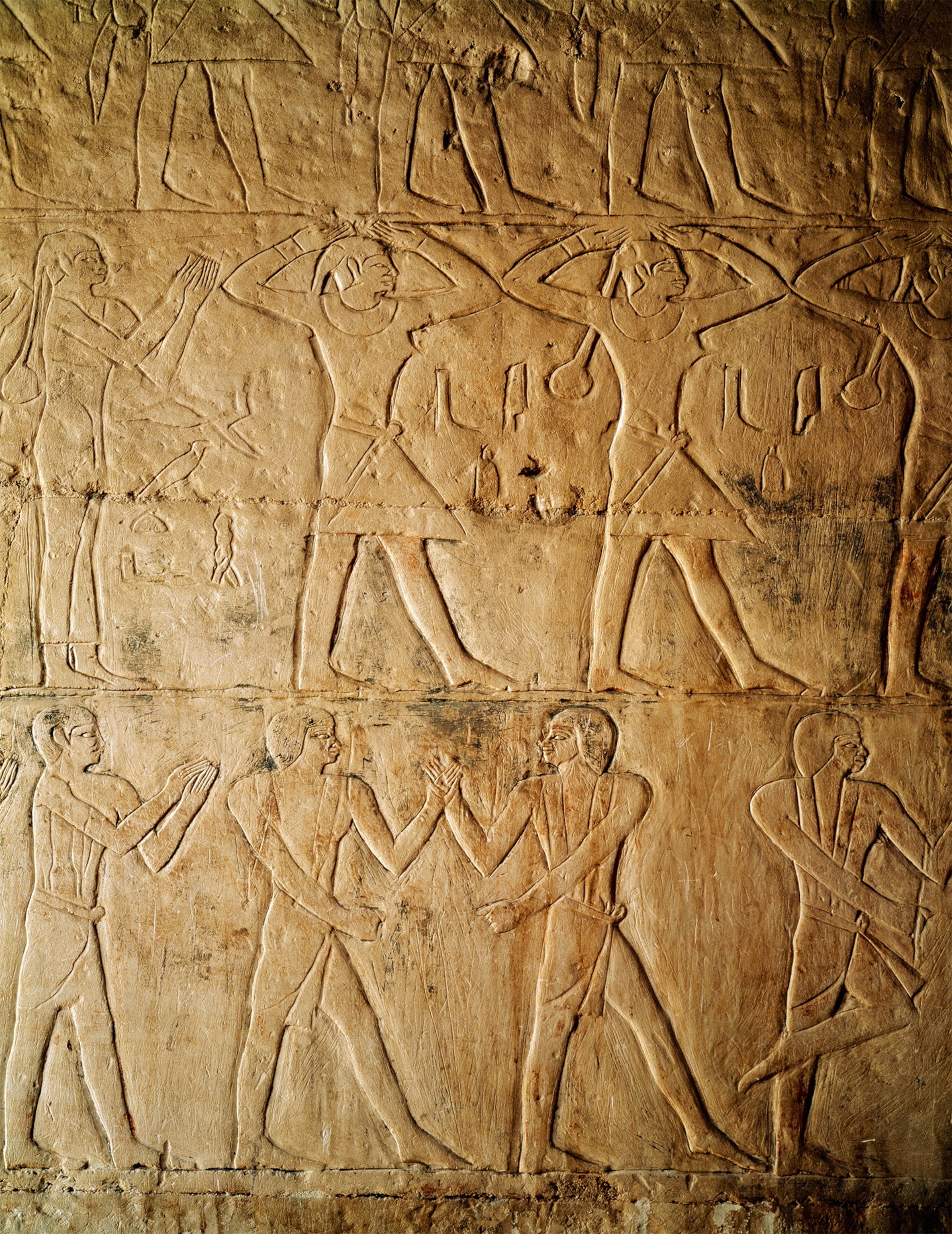

Far from being relegated to rites of passage, religion in ancient Egypt was integral to life. The presence of the spiritual in the physical world was reflected in artistic symbolism, including in the art of dance. The mirror dance featured dancers moving in pairs, carrying wooden slapsticks or castanets in one hand and a mirror in the other. Along with being practical items and casting light during the dance, mirrors had a symbolic meaning. Their disk shape resembled the sun on the horizon, and the sun god Re represented rebirth, which is what Egyptians sought after death.

The dance of the stars symbolized the sun’s passage from east to west, a metaphor for the cycle of life and death. As depicted above, the strongest dancer would stand in the center and hold two lighter dance partners by the wrists, one in each hand.

Scholars link the movements of ancient Egyptian dance to a wealth of modern Mediterranean dance traditions, such as flamenco, as well as the arabesques and pirouettes of ballet. In this way, and through their depictions in ancient Egyptian tomb art, dances meant to ensure life after death for Egyptians have achieved their own kind of immortality.

(The obelisk is an ancient Egyptian architectural feat. So why are so few in Egypt?)