Here’s the difference between a caucus and a primary election

For years, the U.S. selected presidential candidates through caucuses. Now, they only remain in a few states.

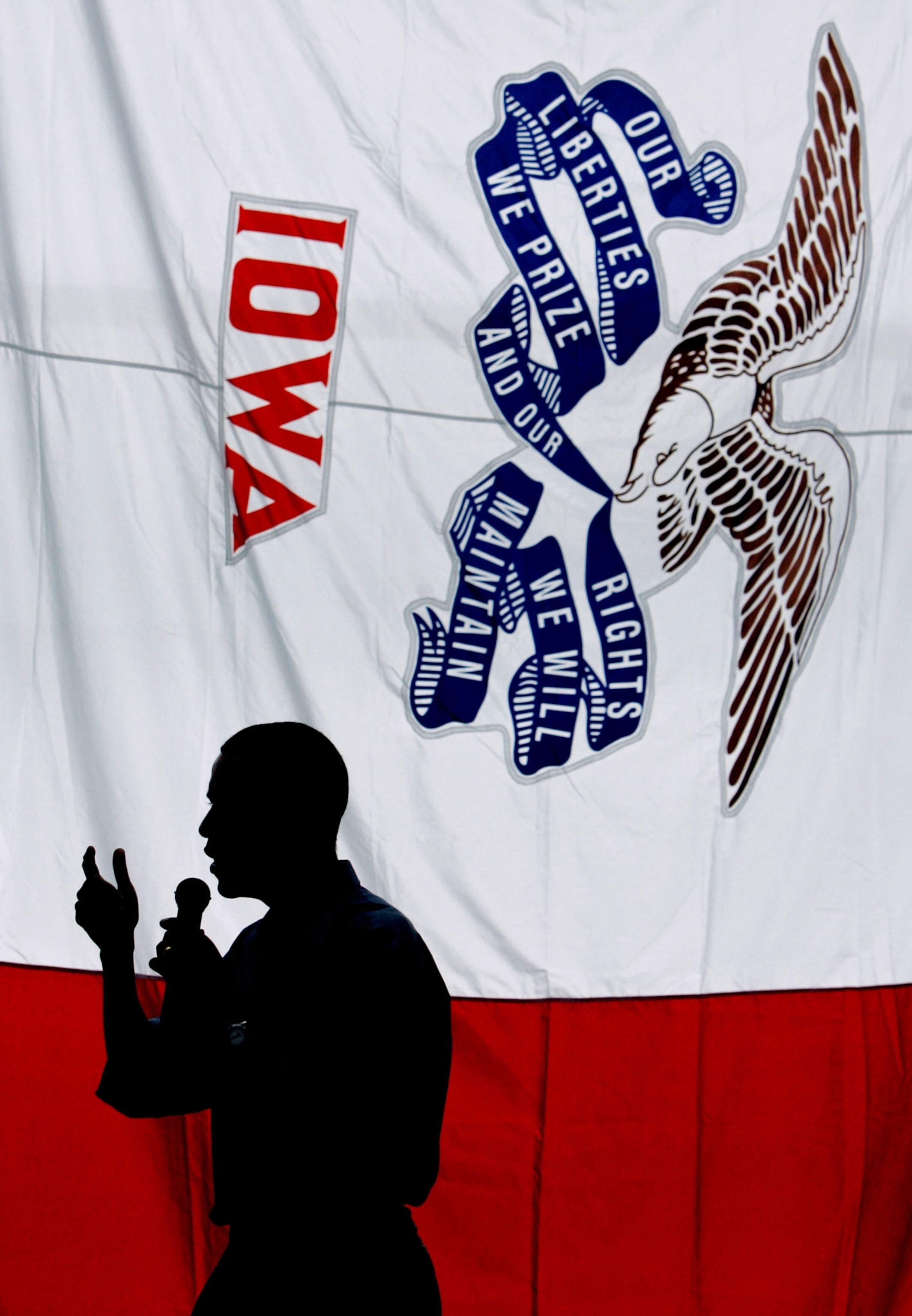

Every four years, Iowans on both sides of the political aisle gather for hours in living rooms, church basements, and now even sites around the world to cast the nation’s first votes on nominees in the presidential election. The Iowa caucus—scheduled this year for Monday, January 15—is both the kickoff to the presidential nomination process and a time-honored political tradition.

But it has lost ground in recent years to its more popular alternative: the political primary. But what is the difference between them—and how did they come to be?

What are caucuses and primaries?

First things first: Caucuses are not primaries. During a presidential caucus, state political party supporters gather to elect delegates to represent them at a state presidential nominating convention. These in-person gatherings can last for hours and involve intense negotiations as people try to convince one another of their preferred candidate’s merits.

A primary is organized by states, not political parties. Rather than requiring participants to gather in one place at one time, a primary is an election. Depending on the state, voters either choose candidates directly or select delegates who will represent their preferred candidate in a statewide party convention, a process known as an indirect primary.

The history of caucuses

In the early history of the United States, caucuses were the norm—though they looked a little different than they do today. In 1796, both parties began to nominate presidential candidates with a secretive caucus of U.S. congressmen, a system known as “King Caucus.” But in 1824, several presidential candidates refused to seek the blessing of King Caucus on principle, and caucuses soon were held on the local level instead. Starting in the 1840s, these state caucuses became the standard way of nominating presidential candidates prior to a national party convention.

(These are four of the worst political predictions in history.)

But there was a downside to these caucuses, too: A small group of party insiders usually dominated these meetings. Party bosses controlled local caucuses, so national candidates had to form coalitions of local and state bosses to gain the nomination.

Beginning in the 1890s, Progressive-era reformers encouraged primary elections as a way to democratize the presidential nomination process by allowing ordinary Americans to voice their political views directly. By 1916, 25 states had switched to primaries. But despite reform, party bosses still held sway over national conventions, often disregarding primary results and making their own decisions on candidates.

Then, after the violent 1968 Democratic National Convention, which resulted in the nomination of Hubert Humphrey, who had not entered any primary elections, the Democratic Party created the McGovern-Fraser Commission to suggest new rules for the party’s next convention. The commission’s recommendations spurred reform in both parties: Beginning with the 1972 election, most states’ parties adopted the primary system.

(This is how the election of 1824 ended the so-called Era of Good Feelings.)

Not Iowa, though, and the state’s traditional caucus system is a point of pride for state voters who argue that caucuses are inherently more democratic than primaries.

Modern caucuses

Unlike the days of closed-door meetings led by party bosses, modern caucuses bring ordinary citizens together to select their preferred candidates. Because Iowa is the first state on the candidate nomination calendar, along with New Hampshire’s primaries, would-be presidents must win these voters to prove their viability on the national stage. A candidate can claim victory in Iowa with a relatively tiny number of votes, explain Tara Golshan and Ella Nilsen for Vox, because so many candidates run at the beginning of the nomination cycle that they split the vote by default. A trouncing in the state often spurs candidates to drop out of the race.

But though Iowans seem committed to caucuses, the rest of the country begs to differ. In 2016, an AP-NORC Center poll found that 81 percent of Americans think primaries are a fairer way to pick candidates than caucuses; just 17 percent preferred caucuses. That falling confidence in caucuses has led to even more states bidding them farewell. After the 2016 elections, 10 caucus states switched to the primary system. In the 2024 presidential election, only a handful of U.S. states and territories will hold caucuses.

Though primaries have their own detractors—who object to the outsized role played by superdelegates in nominee selection—non-Iowa states are increasingly vocal about their discontentment with the state’s role in the presidential nominating process. But for now, the tradition remains intact. King Caucus may be dead, but his Iowan cousin hasn’t quit yet.