How scientists bring ancient faces back to life

Humans attempted to reanimate the skulls of our dead for thousands of years. With the help of modern technology and ancient DNA, it’s now both an art and a science.

It’s a moment that never fails to stop Oscar Nilsson in his tracks—an instant in which archaeology and art collide.

After many months spent reconstructing the facial structure of a long-dead human in his Stockholm studio, Nilsson begins to apply a layer of “skin” to his latest silicone bust. He uses ever-tinier needles to create wrinkles and pores, applies paints that capture the essence of a human epidermis, and pokes infinitesimal hairs onto his creation. Then he opens its eyelids.

“It immediately becomes a face,” says Nilsson, a trained archaeologist and sculptor who specializes in 3D facial reconstructions of ancient humans. “After more than 20 years, it’s still a great day in the studio.”

(Archaeologists give him skulls—Oscar Nilsson brings them to life.)

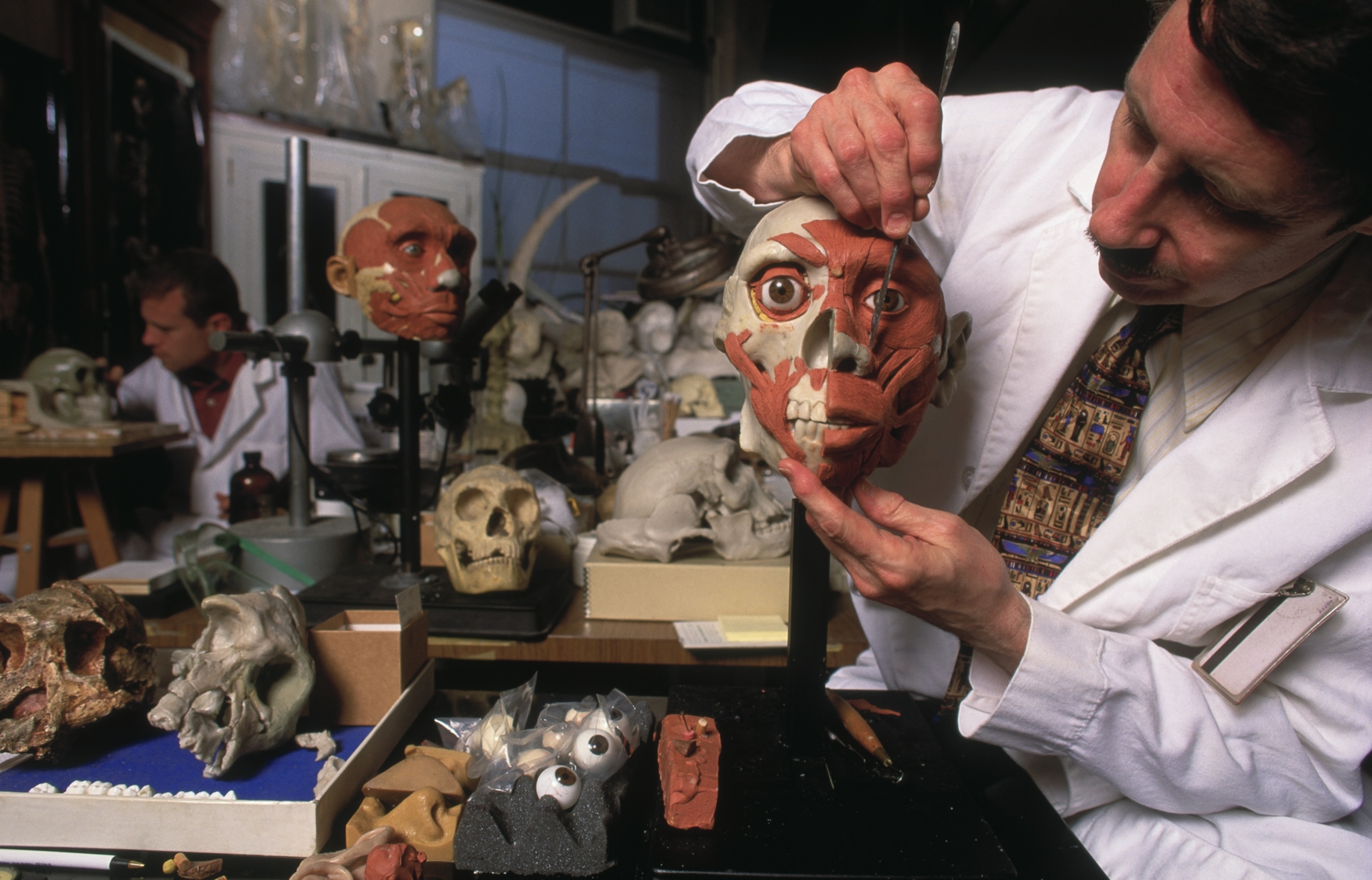

Nilsson isn’t alone: Facial reconstructions are an increasingly popular way of approximating the past. But creating a reconstruction isn’t just a matter of clay and confident hands. It’s a painstaking process that takes art to the brink of science and science to the brink of art—and its results can take your breath away. Here’s how archaeologists bring the faces of human history back to life.

Why we reanimate faces from the past

The practice of facial reconstruction is older than you might think: as one team of bioarchaeological researchers write, “the idea of reanimating a skull has been a part of the human story for thousands of years.” In the Neolithic Levant of about 10,800 years ago and the Late Neolithic Anatolia about 8,500 years ago, they explain, “skulls were unearthed after a socially appropriate amount of time had passed, then covered with plaster, clay, and pigments that were shaped and painted to resemble the dead person.”

The fathers of modern facial reconstruction in the 19th century used similar strategies but added in the knowledge and expertise of skilled physicians and anatomists. Driven by the urge to celebrate and romanticize revered but deceased public figures, they would first examine the bones of a dead person before approximating their appearance in sculpture.

One such sculpture was none other than the legendary composer Johann Sebastian Bach. In a 1894 bid to determine if exhumed human remains discovered in a German churchyard were really Bach’s, German anatomist Wilhelm His attempted to reconstruct the composer’s face. The anatomist did so by applying clay directly to the skull, using data on the average depth of facial tissue he gathered by examining the faces of 27 human corpses. The face that emerged resembled existing portraits of Bach, assuring historians that the skeleton had likely belonged to the late composer—and later served as the basis for future artworks and Bach’s reinterment in Leipzig.

This sparked a growing scientific interest in the anatomy of the human face and the subtle differences in facial depth and tissue formation that make each face unique. The facial tissue thickness data created by these early anatomists are still used by facial reconstructionists like Nilsson.

The first steps of facial reconstruction

Before a 3D facial reconstruction can begin, researchers must collect as much information as possible about their subject’s life. Who were they? Where did they live and die? What’s known about their diet, lifestyle, and health? Today, advances in archaeological analysis make it possible to pinpoint all sorts of information about individuals—from their favorite foods to the type of climate they inhabited—by examining the isotopes of a specimen.

(This 4,000-year-old skull just received a new face.)

And that's often just the beginning: An increasing number of facial reconstructions now also include evidence from DNA analysis, which can pinpoint not just a person’s ancestry, but their likely skin, hair, and eye color. Ancient DNA analyses “have been a gamechanger for me,” says Nilsson, as it takes the guesswork out of many facets of reconstruction once left up to the artist.

An individual’s sex, ethnicity, and weight and age at death all inform facial depth and other features, while their skull also possesses subtle markings that indicate the places where tissue was once connected to bone. “Sometimes it’s very easy to see exactly where the muscle was placed, because it leave stress marks or ridges on the skull,” says Nilsson. All this information helps the reconstructionist decide what goes where, resulting in an eerie anatomic model.

From archaeology to art

For the next step, a thorough understanding of facial anatomy is key: Sculptural reconstructionists like Nilsson meticulously mold individual pieces of cartilage and muscle from clay, superimposing each directly onto a 3D printed replica of their subject’s skull.

Though 3D facial reconstruction can be attempted with the help of a computer, Nilsson prefers a hands-on approach. “I’ve been interested in faces for as long as I can remember,” he says.

(Watch scientists reconstruct the face of a 9,000-year-old teenager.)

As the mosaic of educated guesses slowly takes on a human guise, the reconstructionist moves from recreation to interpretation—using what is known about the individual to shape their eyes, mouths, and skin. For example, he might add wrinkles or sun spots to the face of someone who died in old age, or include evidence of diseases discovered during the DNA research.

“I often feel my work is a two-step process,” says Nilsson. First, his job is to act as an impartial observer, obeying the rules of forensic archaeology and cleaving to hard data. “And then I hand it over to the artist,” he says.

Eventually, the clay-covered skull is used as the basis for a molded silicone bust of the individual. Delicate, subtle paint and meticulously applied hair breathes life into the reconstruction.

The ethics of such reconstructions continue to spark debate within the scientific community. After all, there’s no way to know if these depictions are accurate, and the person being replicated has no say in the matter. Then there’s the quandary of how to prevent the public from drawing too-broad conclusions about the sweep of human history from a single face.

But there’s another way to look at the sometimes-uncanny faces that emerge from the process. Each facial reconstruction is an opportunity to reflect on—even pay tribute to—an individual whose time is far in the past. Reconstructions add a layer of humanity to what otherwise might appear to be simply a heap of human bones. In other words, this complex dance between art, anatomy, and archaeology can bring the past almost to life—one eyelash, pucker, and pore at a time.