Americans knew their booze was poisoned—and drank it anyway

During Prohibition, the U.S. government added toxins to industrial alcohol, knowing it could kill. The result? A chemical war that targeted the poor and reshaped public trust.

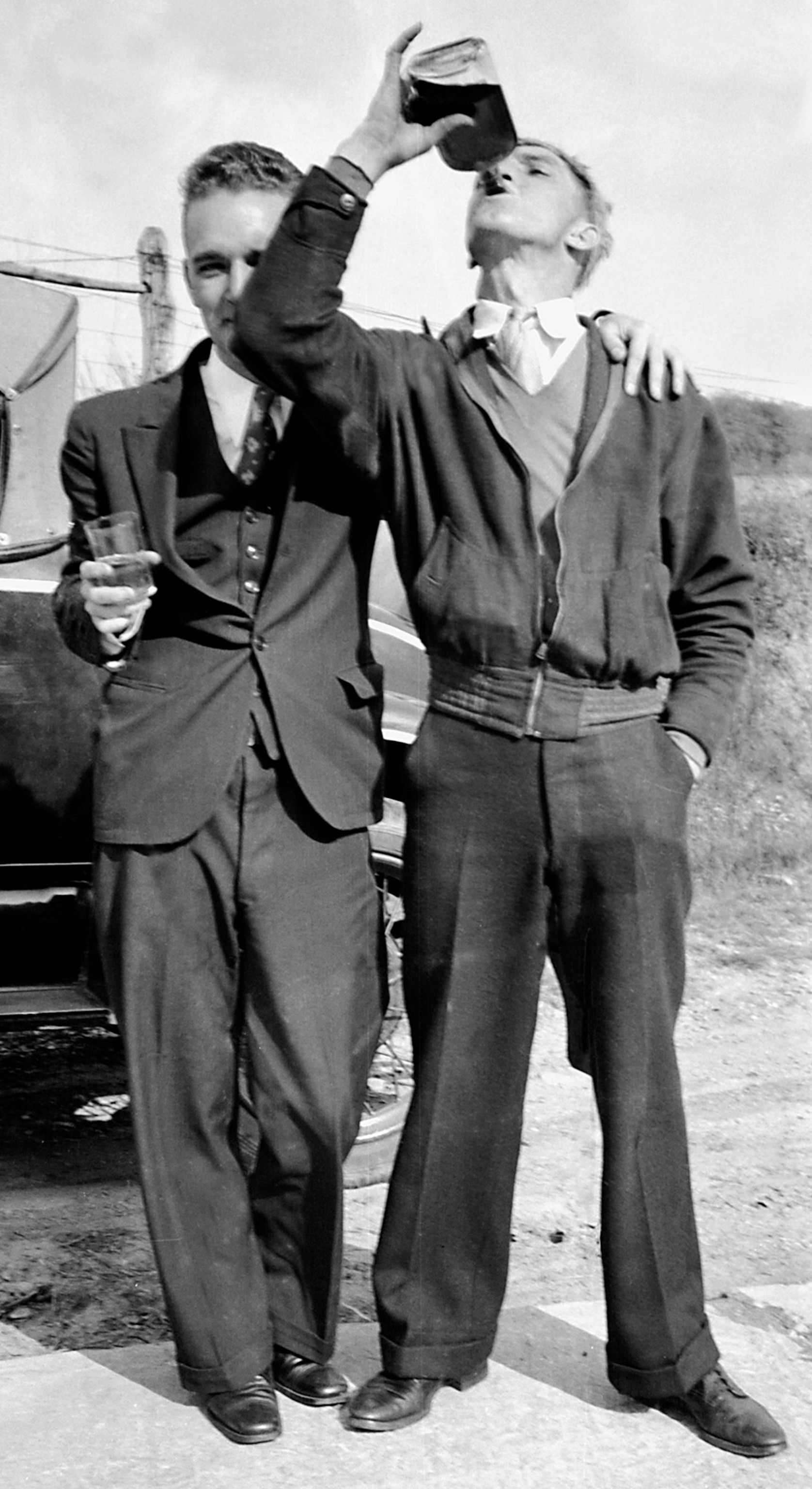

When bluesman Ishman Bracey poured himself a drink in Jackson, Mississippi, he didn’t know his luck had just run as dry as the nation’s taps.

A couple of weeks later, his legs were tingling. With rumors of a polio surge going around, he rushed to the hospital. But it wasn’t a virus. He’d been poisoned.

The cause? A government policy that made drinking alcohol not just illegal—but lethal.

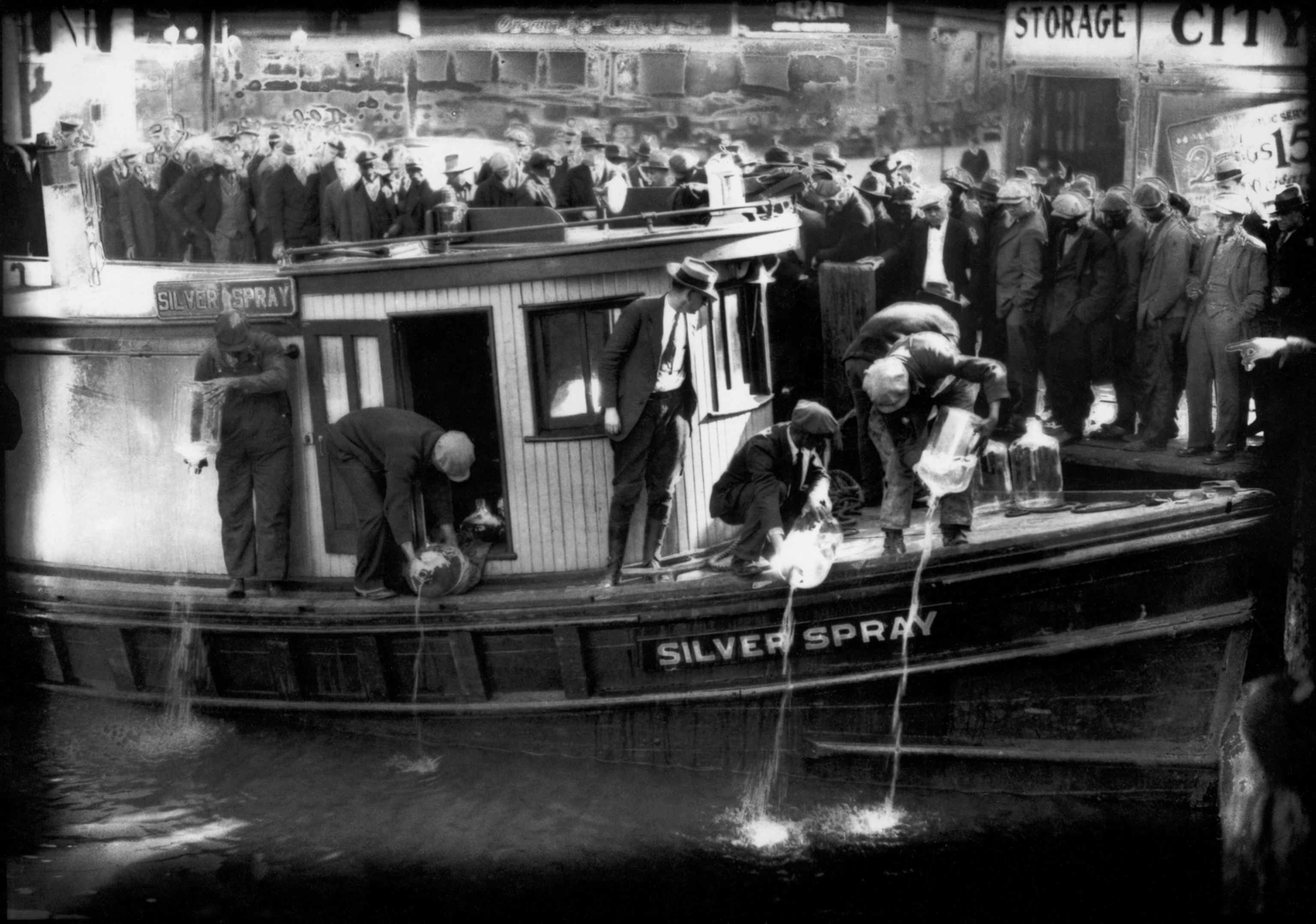

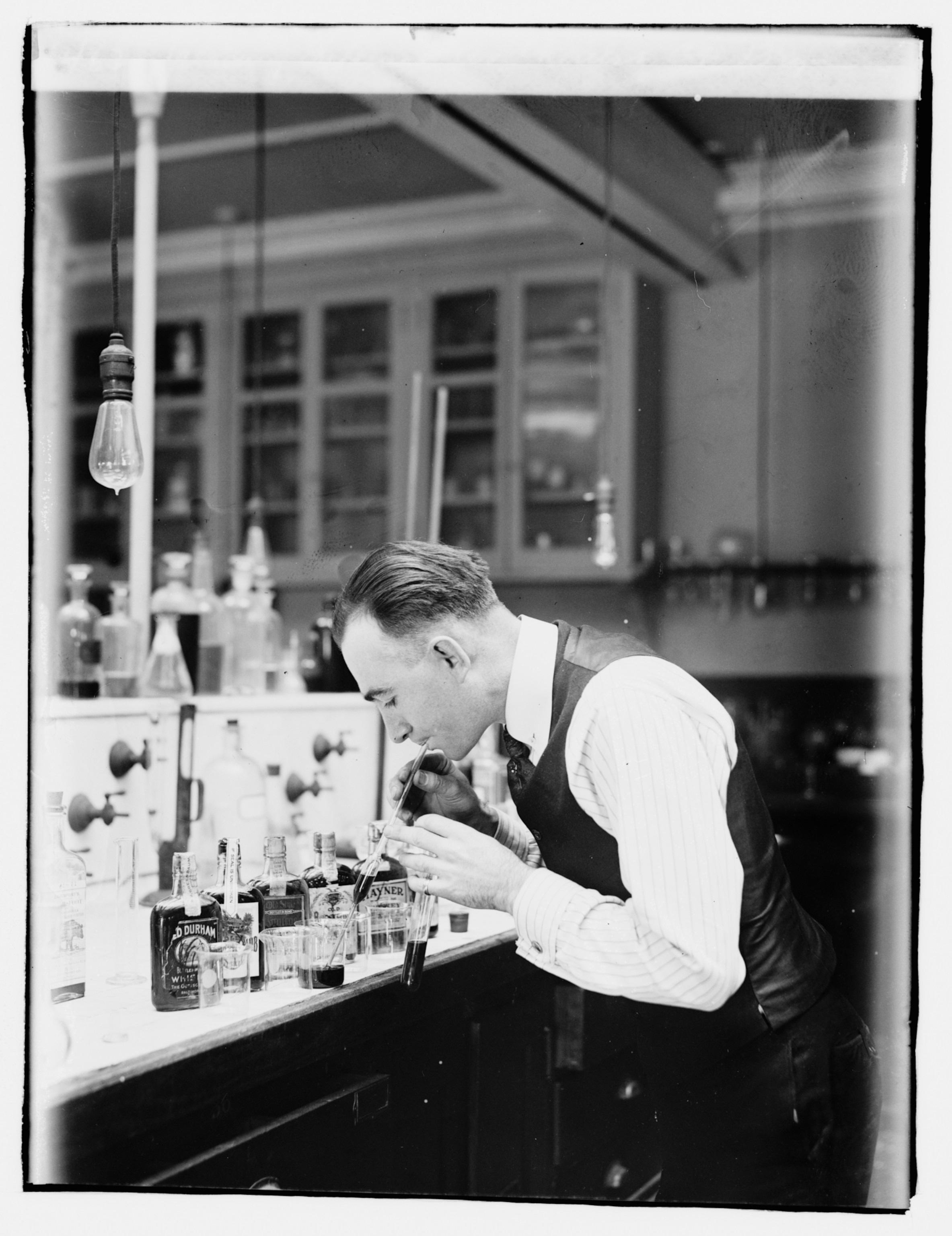

During Prohibition, not all alcohol was banned — just drinkable, non-medicinal alcohol. To prevent bootleggers from repurposing industrial alcohol, the U.S. government launched what it called the “Noble Experiment,” adding toxic chemicals like methanol and benzene to render it undrinkable. According to a New York Times headline at the time, the government planned to “double alcohol poison content.” By the time Prohibition ended in 1933, more than 50,000 Americans had died from drinking tainted alcohol—a staggering 600 percent increase in alcohol-related deaths from previous years.

The drink that poisoned a generation

If the denatured alcohol didn’t kill enough consumers, the conditions surrounding it often did. Bootleggers, eager to meet demand, diluted, repackaged, and tried to counteract the toxic additives in industrial alcohol. Thousands died in what researchers have called “The chemist’s war of Prohibition.”

“It was more out of ignorance than actually trying to kill people who drink,” says Zach Jensen, a education specialist at the Mob Museum in Las Vegas. “I would blame the bootleggers. They’re who actively used this poisonous alcohol, but I don’t think the government is completely inculpable in that.”

That culpability didn’t go unnoticed. For instance, Charles Norris, New York City’s first chief medical examiner, was a leading voice against alcohol’s denaturation, calling it “our national experiment in extermination.”

(Humanity's 9,000-year love affair with booze.)

“Generally, politicians don’t like to kill people that live for them,” says Peter Liebhold, a Smithsonian curator emeritus. “Even criminal organizations don’t like killing their consumers because they’re in the business of selling stuff.”

But on Christmas Eve of 1926, 60 people wound up in New York’s Bellevue Hospital from drinking tainted liquor. Eight of them didn’t live to see Christmas Day, and by New Year’s Eve, the death toll climbed to 31.

Horrified, Norris swiftly gathered press. “The government knows it’s not stopping drinking by putting poison in alcohol, yet it continues its poisoning processes, headless of the fact that people determined to drink are absorbing that poison,” he told reporters. “The US government must be charged with the moral responsibility for the deaths.”

A policy with unequal costs

But not everyone saw the government as the villain. Wayne Wheeler, chief lobbyist of the Anti-Saloon League, argued that blame didn’t lie with the law but with drinkers themselves.

“The person who drinks this industrial alcohol is a deliberate suicide,” Wheeler said in a 1926 statement. “The very fact that men will gamble with their lives to get a drink shows how deeply this habit was fixed. To root out a bad habit like that costs many lives.”

(Meet the female sheriff who lead a Kentucky town through Prohibition.)

That statement outraged some lawmakers. New Jersey Senator Edward Irving Edwards called it “legalized murder” and declared the government “an accessory to the crime.”

However, according to Liebhold, while the government denatured alcohol to prevent consumption, it was criminals who made it available—often in dangerously impure conditions.

So, was it murder? Maybe not. But the government’s attitude was that if you’re willing to drink, you’ll suffer the consequences—which weren’t equally felt. Wealthier Americans could obtain government-approved medical whiskey or sip cocktails overseas on booze-cruises. Working-class communities and people of color lacked such options and were often the ones drinking what was available—and dying from it.

One popular liquor alternative was “Ginger Jake,” a patent medicine that was up to 80 percent alcohol. However, to keep up with demand while avoiding detection, a manufacturer added TOCP. This slow-acting poison attacks the nervous system, causing paralysis or a distinctive limp known as “Jake Leg.” Though the exact number is unknown, 35,000 Americans joined the “United Victims of Ginger Paralysis Association,” and estimates range from 50,000 to 100,000 casualties.

Bluesman Ishman Bracey memorialized the condition in his song “Jake Liquor Blues,” singing, “It’s the doggonest disease ever heard of since I was born. You get numb in front of your body, you can’t carry any lovin’ on.”

A war for taxes, not just temperance

While framed as a moral crusade, Prohibition was also political. Seven years before it began, the 16th Amendment created a federal income tax—replacing the government revenue once generated by alcohol sales. Denaturing alcohol made it unfit for consumption and, therefore, untaxable.

(Were humans hardwired to drink alcohol?)

“After a period of time, they knew they were killing people—and they didn’t stop,” says Deborah Blum, a Pulitzer Prize-winning science journalist and expert on the history of poison in America. “I don’t think they were intentionally trying to kill people, but they were, so I think that’s the acceptance of collateral damage, like in any war.”

A legacy that still lingers

So what does this tell us? Harvard history professor Lisa McGirr argues in her book, The War on Alcohol, that this was really the rise of the penal state. It saw the rise of wiretapping, mass incarceration, and federal policing—tools that would later expand during the War on Drugs and beyond.

“It’s the people who pay when governments give themselves the mantle of moral authority and high-ground that justifies—whatever I do is justified because I’m doing it for your good,” Blum says. “And I decide what your good is.”