Before the Great Migration, there was the Great Exodus. Here's what happened.

During this pivotal late 19th-century migration, African Americans fled the post-Reconstruction South for the promise of freedom and land in the Midwest.

Angela Bates has lived across the United States, but the only place she’s ever called home is Nicodemus, Kansas.

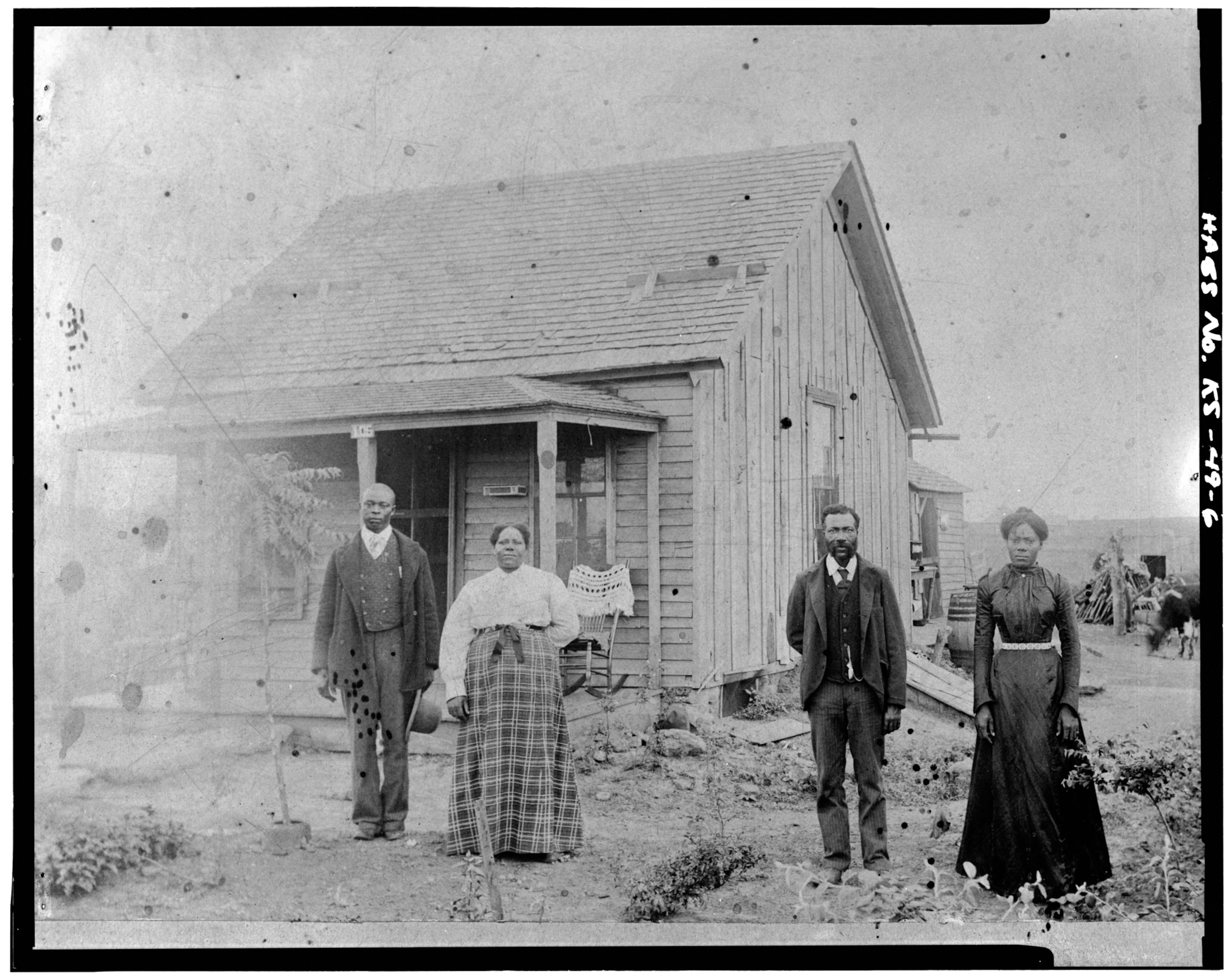

In 1877, her great-grandmother Emma Johnson and other ancestors moved from Georgetown and Lexington, Kentucky, to establish one of the first all-Black towns west of the Mississippi River. Her family’s move to Kansas was a precursor to the Great Exodus, the first voluntary mass migration of African Americans from the South to what we now call the Midwest, including Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma.

After the Civil War, tens of thousands of newly freed Black families fled the South after several regional states passed oppressive “Black Codes” with the intent to restrict the freedom and rights of African Americans.

“It was the first major instance of African Americans…‘voting with their feet,’ demonstrating their discontent with the South,” says Damani Davis, reference archivist for the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

In a way, the Great Exodus and Nicodemus helped rewrite Black history in America. Nestled in the expansive Kansas prairie, Nicodemus’ legacy reminds us of a pivotal chapter in American history and the enduring spirit of those who sought freedom and opportunity against formidable odds.

The impact of post-Reconstruction policies

When President Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew federal troops from the South in 1877, the region quickly reversed many of the economic and political gains African Americans had achieved during the 12-year Reconstruction period.

The Ku Klux Klan rose to power, using lynchings and mob violence to terrorize Black communities. Southern states enacted Black Codes, local laws intended to disenfranchise African Americans and force them into exploitative labor systems like sharecropping. According to Davis, these despotic rules laid the groundwork for the more formalized Jim Crow laws that followed.

(Here’s how the Harlem Renaissance helped forge a new sense of Black identity.)

Faced with increasing violence and oppression, Black Americans began to look for new lands where they could find safety and autonomy. Southern conventions, where African Americans discussed politics and social concerns, sparked stories of a “promised land.” The idea of owning and farming land independently in a free state was especially appealing compared to the harsh realities of sharecropping in the South. This vision was reminiscent of the biblical exodus, leading to the migrants being called “Exodusters.”

The Homestead Act of 1862 fueled some of the excitement over reaching Kansas. This law allowed adults to claim 160 acres of land at a low cost if they moved to Kansas and other parts of the Midwest and worked the land for at least five years. Kansas’ proximity to the South made it more accessible than more distant western territories, though the journey was still out of reach for many Black Americans.

“Far more people attempted to go to Kansas than actually succeeded,” says Davis. In “some of the Senate testimony that I read, you have individuals…describing throngs of individuals just pleading and trying to find steamships that would take them up the Mississippi River.”

The exodus to Kansas

In 1880, Congress formed a Senate committee to investigate why thousands of African Americans had moved to Kansas and why many more desired to do so. The committee interviewed over 150 people, including Benjamin “Pap” Singleton, a former enslaved person who had escaped from Tennessee to Canada and returned after the Civil War.

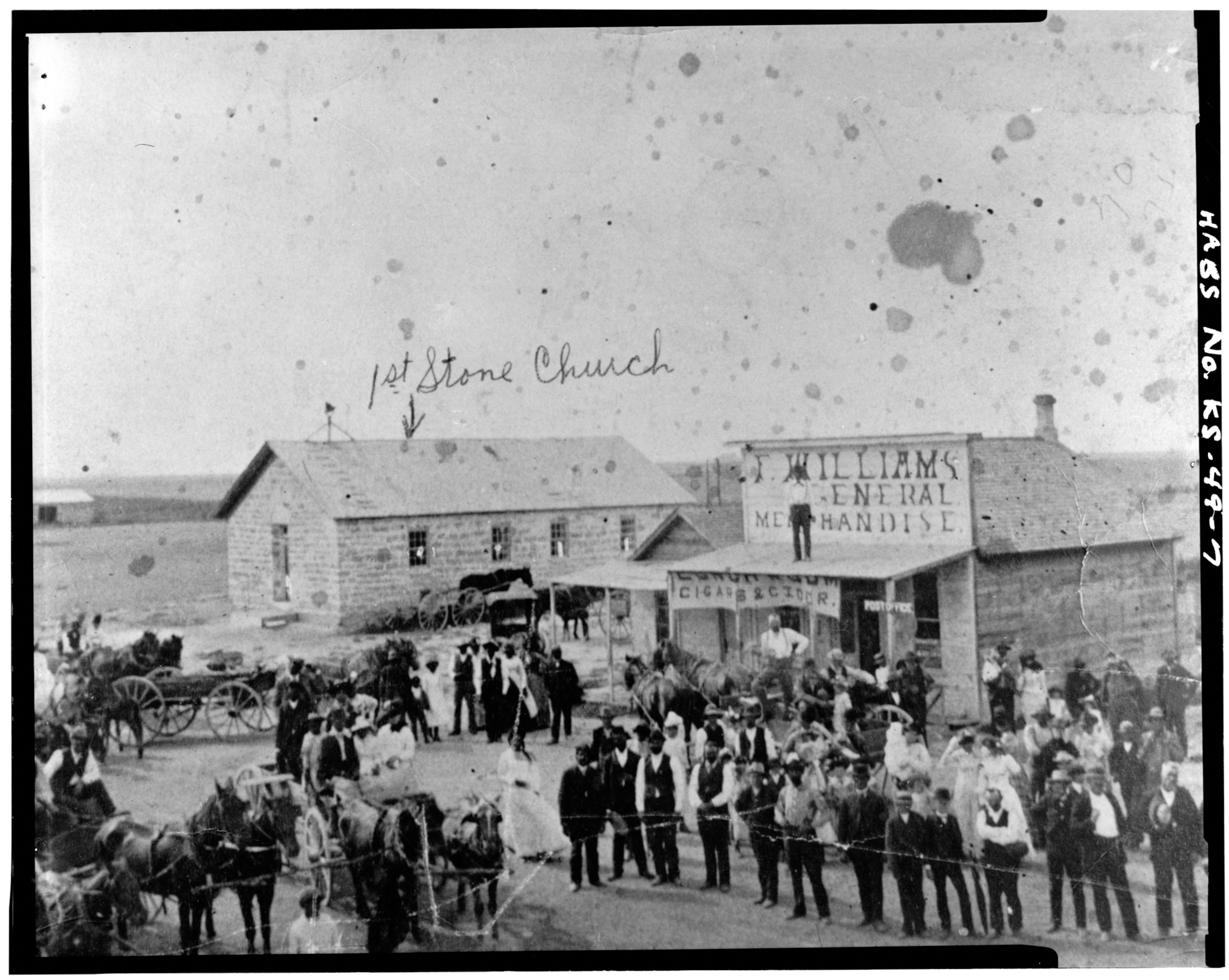

In his testimony to the Senate, Singleton said his community didn’t want to leave the South but that Black Americans needed to go to teach the South a lesson. In 1873, Singleton led 300 African Americans from southern states to the southeastern corner of Kansas, to a new home he called Singleton Colony. A few years later, he helped establish the town of Nicodemus, Kansas, for fellow Exodusters.

(These African American history museums amplify the voices left unheard.)

The Great Exodus peaked in the spring of 1879 when about 6,000 African Americans left Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas on trains and steamboats heading to St. Louis, the halfway point in the Exoduster journey, before crossing Missouri to settle in areas in Topeka and Atchison. These migrants faced numerous hardships, including a lack of resources and hostile environments.

By 1880, while some continued to migrate, the mass migrations of the 1870s had largely subsided.

Davis says that outside of the historical research community, fewer people know about the Great Exodus than about other mass movements because there aren’t as many pop culture references to make it top of mind.

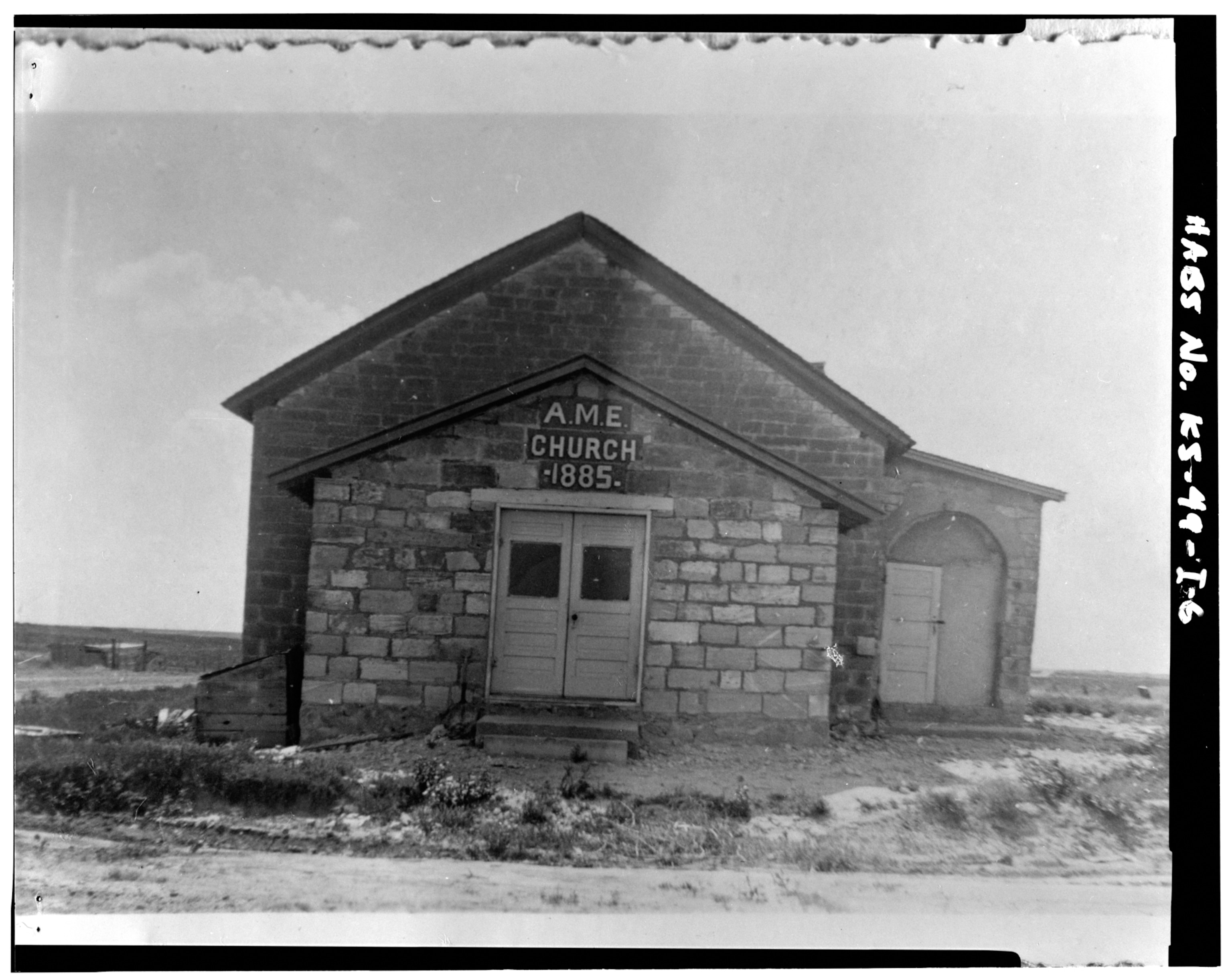

But Bates says you cannot talk about the history of the West without including Nicodemus. Efforts to preserve the town’s historical sites, such as the Nicodemus National Historic Site, ensure that its founding by freed African Americans in 1877 remains vivid in collective memory.

“Nicodemus, and all the Black towns that eventually followed, spoke volumes in terms of what African Americans were doing with their freedom,” she says. “Starting their own all-Black towns? That’s phenomenal.”