A new battle zone for the coronavirus looms: the developing world

People in Mandalay, Myanmar’s second-largest city, are coming together in the face of a possible catastrophe.

Mandalay, Myanmar — “Do you know how to distribute food?”

Aung Ko Ko was trying to learn—fast—how disaster relief works. The young hotel manager in Mandalay, the second-largest city in Myanmar, was scouring the web on his smart phone, searching for nutritional guidelines for food aid during famines, a bleak but possible endgame of the COVID-19 pandemic among the world’s weaker economies. He texted business friends to organize a head count of his city’s most vulnerable citizens: the homeless mainly, but also destitute day laborers who couldn’t self-isolate without starving. And he even resorted to asking the advice of the last guests at his all-but-empty tourist lodge, whose business was wiped out by the worst global health crisis in a century.

“We don’t really know what we’re doing,” Ko Ko admitted, pulling on his kitchen staff’s plastic cooking gloves as makeshift antiviral protective gear, before going out to deliver bags of biscuits from a motorized rickshaw. “But we’re trying to help.”

Mandalay could certainly use it.

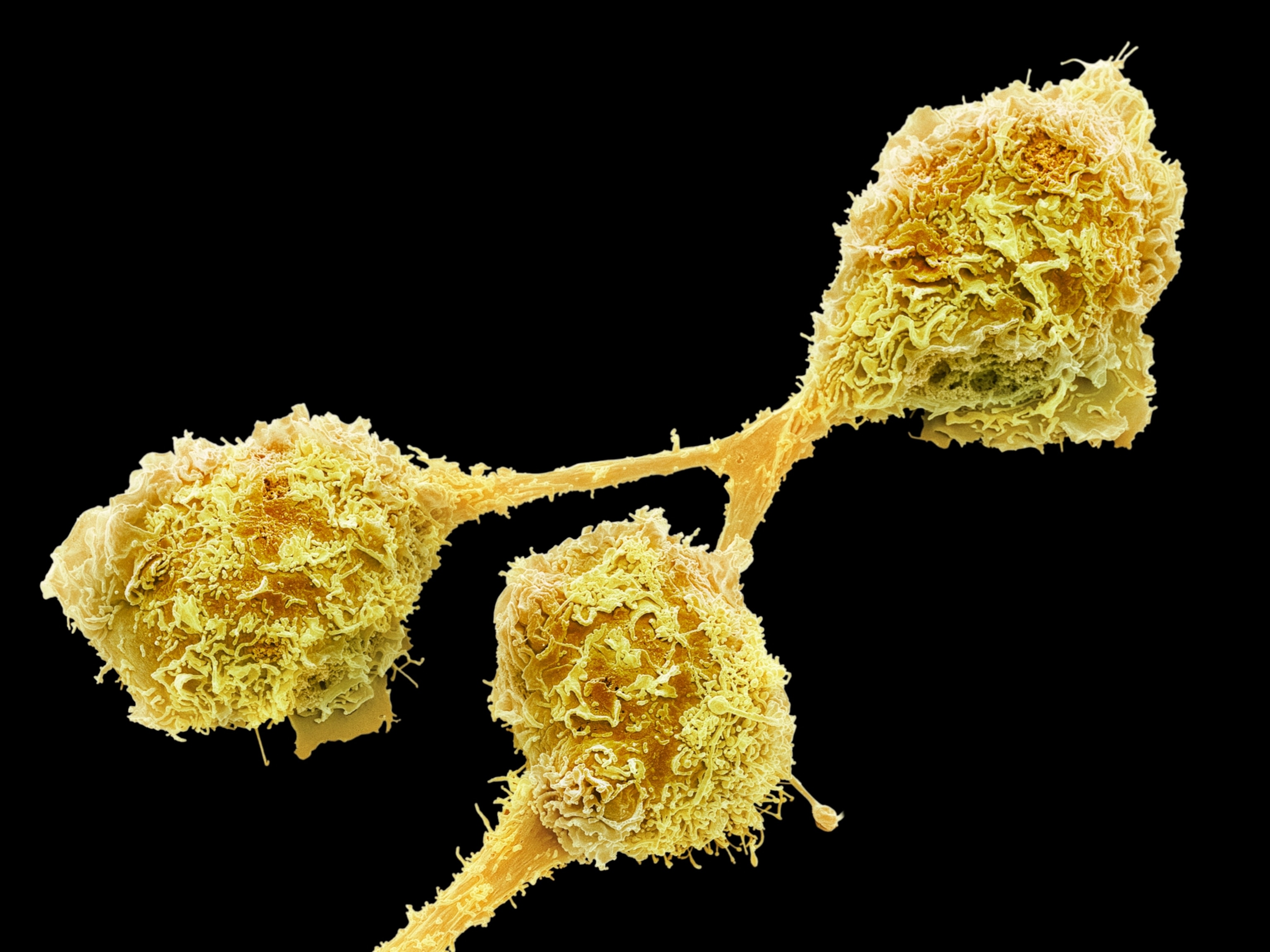

One of the poorer countries in the world with a per capita income of $1,200, Myanmar is girding for the brutal onslaught of COVID-19, the novel coronavirus that has surged across the Earth and overwhelmed the economies and hospitals of far richer nations. As of April 4, the Myanmar government had officially tallied 21 positive cases of the disease. But doctors here warn that this improbably low number masks a dire reality: With minimal testing available and a population of 54 million, the country’s actual infection rate is likely far higher. And once the infection peaks, it easily could smother the nation’s frail public health system. In Mandalay, a city of 1.2 million—about the size of Dallas or Prague—just a handful of life-saving ventilator machines are available to medical teams staffing the sole isolation ward.

“Why talk ventilators?” Khun Kyaw Oo, a doctor involved in the city’s emergency planning committee, said tersely. “We don’t even have enough surgical masks.”

Even basic hygiene products such as hand sanitizer were unobtainable in Mandalay, Kyaw Oo said. Chemistry students at a local university were recruited to mix batches of the antiviral hand-wash in their labs.

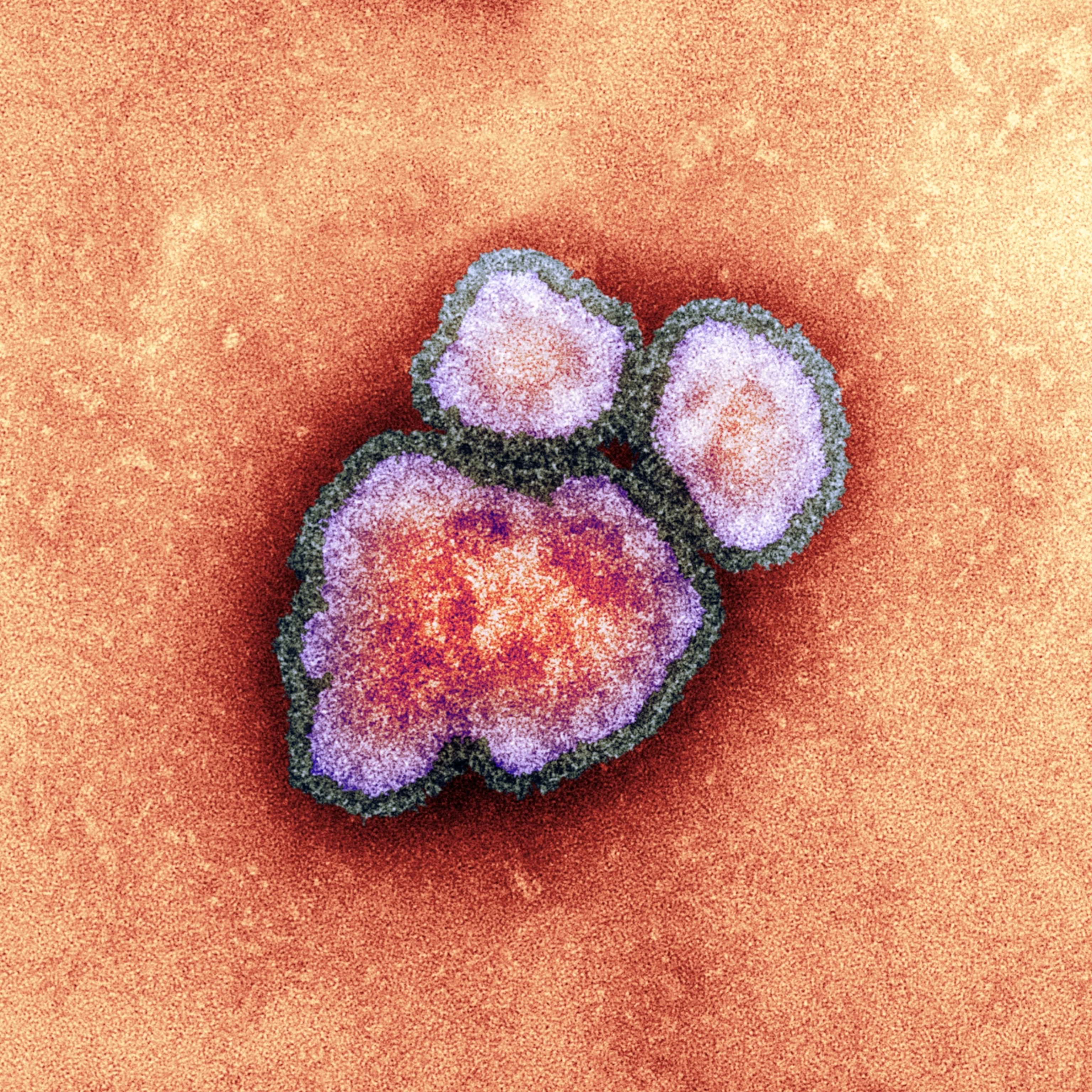

Since COVID-19 first erupted in China in December and began its devastating race across the continents, the pandemic’s early outbreaks have burned hottest in the richer, globalized quarters of the world linked by busy commercial air routes—Europe and the United States.

But that’s set to change, disaster relief experts warn, as the highly contagious virus begins spreading through the poorer societies of the planet. There, threadbare health care services, the impossibility of social distancing in packed slum communities, and an absence of economic safety nets are incubating a human tragedy of potentially cataclysmic scale.

It is clearer than ever that none of us will be safe until all of us are safe.José María Vera, Interim Executive Director of Oxfam International

“Currently, rich countries are the epicenter of this deadly virus,” José María Vera, the Interim Executive Director of Oxfam International, wrote last week in a call for a massive international aid program to brake the virus’s impact in developing countries. “But we must talk of the world. We all need each other’s help right now. It is clearer than ever that none of us will be safe until all of us are safe.”

Affluent Spain provides one doctor for every 250 citizens, Vera noted, and yet the death toll there has rocketed to more than 12,000, the second highest in the world after Italy. “Now consider a country like Zambia which has one doctor for 10,000 people,” he wrote.

As coronavirus infections climb past 1.2 million worldwide, the United Nations has launched a $2 billion emergency medical fund to help poor nations confront the pandemic. But that stopgap sum—less than a thousandth of the total the United States so far has earmarked for its own pandemic recovery—won’t even begin to soften the virus’s shockwaves across vulnerable regions already reeling under the burdens of poverty, war, and climate change.

According to the UN, economic losses caused by the pandemic could exceed $220 billion in developing countries, “impacting education, human rights and, in the most severe cases, basic food security and nutrition.” More than eight million people in the Arab world may teeter into extreme poverty, one study says. And in India, a 21-day general lockdown now threatens the wheat harvest in the world’s second-largest producer of food grains.

Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, awaits the storm.

Early on, its government was criticized for being too slow in reacting to the pandemic. (Last month, an official spokesman asserted that Myanmar’s “lifestyle and diet” offered a good defense against COVID-19.) But the authorities have mobilized since, closing restaurants and national borders, urging people to stay indoors, and requiring thousands of frightened migrant workers rushing home from abroad to self-quarantine.

In wealthier nations, such measures appear obvious.

But in places where millions eke out lives week-to-week—or in extreme cases, even meal-to meal—such policies present agonizing choices.

“My business is dead,” said Yin Yan Mar, whose noodle stall in Mandalay was shuttered by the quarantine. “For the time being, I’ve stored food for two weeks. After that, I have no plan B. Five people depend on me.”

Once roaring with trucks, scooters, and rickshaws, the streets of Mandalay are silent today.

In the face of a looming COVID-19 disaster, many citizens are banding together spontaneously, hoping to barricade their city from collapse.

A gold-leaf manufacturer shelters 15 workers, idled by the virus, for free. “They’re going to get free food too for as long as we have money to buy it,” said Sithu Naing, the sales manager.

One landlord, terrified of contagion, ejected several doctors and nurses from their apartments. Guesthouses, long abandoned by tourists, immediately offered them rooms gratis.

And the hotelier Aung Ko Ko rattles around Mandalay’s harder edges, looking for the hungry. The poor most exposed to the pandemic, he learned, have no means of cooking dry rice. So he hands out fruit and canned goods instead.

“Do nothing, get into no mess, and you’re safe,” Ko Ko said, quoting a Burmese aphorism. “This is not true anymore.”

Paul Salopek won two Pulitzer Prizes for his journalism while a foreign correspondent with the Chicago Tribune. Follow him on Twitter @paulsalopek.