An exclusive look inside the restored Notre Dame—before it reopens its doors to the public

Five years after a catastrophic fire, Paris's beloved cathedral will open to great fanfare. Nat Geo got exclusive access to witness how an army of architects and artisans rebuilt the church back to its sacred splendor.

The fire that came close to destroying the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris started under the roof, in the ancient wooden attic, near the base of the spire. It began a little after 6 p.m. on April 15, 2019—the Monday of Holy Week, six days before Easter. Inside the church, a Mass was under way. My wife and I had arrived in the city the day before, and at around seven that Monday evening we just happened to be passing by. From the window of our cab, on the Pont Saint-Michel, we caught sight of a flickering patch of orange on the roof. Minutes later, stopped in traffic, we saw flames shoot up the wooden spire. Disbelief gave way to shock: Notre Dame was really burning.

No cathedral is more important, to France or to the world. For more than 800 years Notre Dame has stood at the center of French life and has been the setting for historic events both religious and secular. In 1239, King Louis IX, also known as St. Louis, delivered what was purported to be Jesus’ Crown of Thorns to the cathedral. In 1944, as German bullets were still flying outside, Gen. Charles de Gaulle attended a Mass to celebrate the liberation of Paris. Through it all, Notre Dame largely escaped the bombs and blazes that ravaged other cathedrals. An island of stability in a sea of change, it became one of the world’s most visited monuments—as well as a place millions hold sacred.

When we returned to the scene later that evening, the spire had fallen and the lead roof had melted. From the darkness on the Right Bank, we gazed at the stone gable of the north transept, and through the small rose window we saw the flames consuming the oak roof trusses. On the banks and bridges of the Seine, thousands had gathered to watch, drawn to the catastrophe and to the moment of communion. People were spreading the news on their phones. Some were singing the Hail Mary. We were visitors, but for most of the crowd this was home, and a piece of their hearts seemed to be dying.

Now, five and a half years later, Notre Dame has been brought back to life. In early December, the archbishop of Paris is scheduled to celebrate a festive Mass in the restored church. That week the great doors will open to the public—and offer a measure of healing to what has been a public trauma. National Geographic was granted special access to the years of work by architects, craftspeople, and scientists that has led to this moment. In the summer of 2021 I returned for the first time since the fire, as the reconstruction was about to begin. This past summer I went back again to witness its final stage—and also to learn about the clergy’s plan for Notre Dame. I came to appreciate the great lengths thousands of people have gone to not only to preserve this exquisite medieval monument but also to revive it as a living church.

There had never been a doubt that Notre Dame would be rebuilt. But what form would it take? After the fire, French president Emmanuel Macron decreed that the cathedral should be restored, “more beautiful than ever.” He set an ambitious goal to have the work completed by 2024 and financed by the 846 million euros that have been donated since the disaster.

Macron suggested that something structurally new would be nice, instead of the same old spire. Architects responded eagerly with far-fetched ideas for a glass roof or a crystal spire. Preservationists were appalled, including chief architect of historic monuments Philippe Villeneuve, who at the time of the fire was already leading a renovation of parts of Notre Dame. From Villeneuve’s perspective, adding a modern spire would have been like giving “Mona Lisa” a nose job. Whereas restoring Notre Dame as it was, architectural historian Jean-Michel Leniaud told me back in 2021, with limestone, oak, and lead, would be a cathartic act—a way to purge the grim memory of that night and to grieve the loss of the original structures.

In the end the preservationists won: Notre Dame has been rebuilt exactly as it was before the fire and as it was left in the 19th century by Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, a pioneer of restoration. “We don’t have the right to touch it; we’re restoring it,” Villeneuve said. “We leave no trace of our passage.”

And yet the inside of the cathedral, to anyone who has visited before, will seem utterly transfigured—brighter than any person alive has ever seen it. Walls, stained glass, paintings, and sculptures have all been cleaned and restored, all at once, for the first time since the 19th century. Visitors “will be stupefied, awestruck, by the interior of the cathedral,” said Philippe Jost, president of the special public authority overseeing the restoration. “It will be a shock.”

But the interior will be new in another way. While the building is owned and managed by the French state as a protected historic monument, the interior furnishings, which were extensively damaged in the fire, were for the most part not historic, and they belong to the Roman Catholic diocese of Paris. Church officials chose to undertake a complete redecoration. The cost is small in the context of the overall restoration—but it will have a big effect on how visitors experience the church.

Early this past summer, I paid a visit to a foundry in the Rhône Valley to see some of the church’s new furnishings. There I met Guillaume Bardet, a sculptor and designer who had been commissioned by the diocese to create a new altar and other liturgical objects. In the furnace room, we watched two workers in visors and heavy aprons decant molten, white-hot bronze into a series of molds. Rough, unfinished sections of Bardet’s new baptismal font sat on the floor nearby. His altar stood in the next room, waiting to be polished.

Working with clay models, he explained, he had searched for shapes that felt simple and immutable. The bronze altar is massive and looks rooted to the spot, yet its curved sides evoke a pair of uplifted arms. The hope is that it will speak not only to the faithful but also to the larger number of tourists who are unfamiliar with Catholicism or even Christianity. “They too have to understand,” Bardet said. “They have to understand that we’re talking about the sacred.”

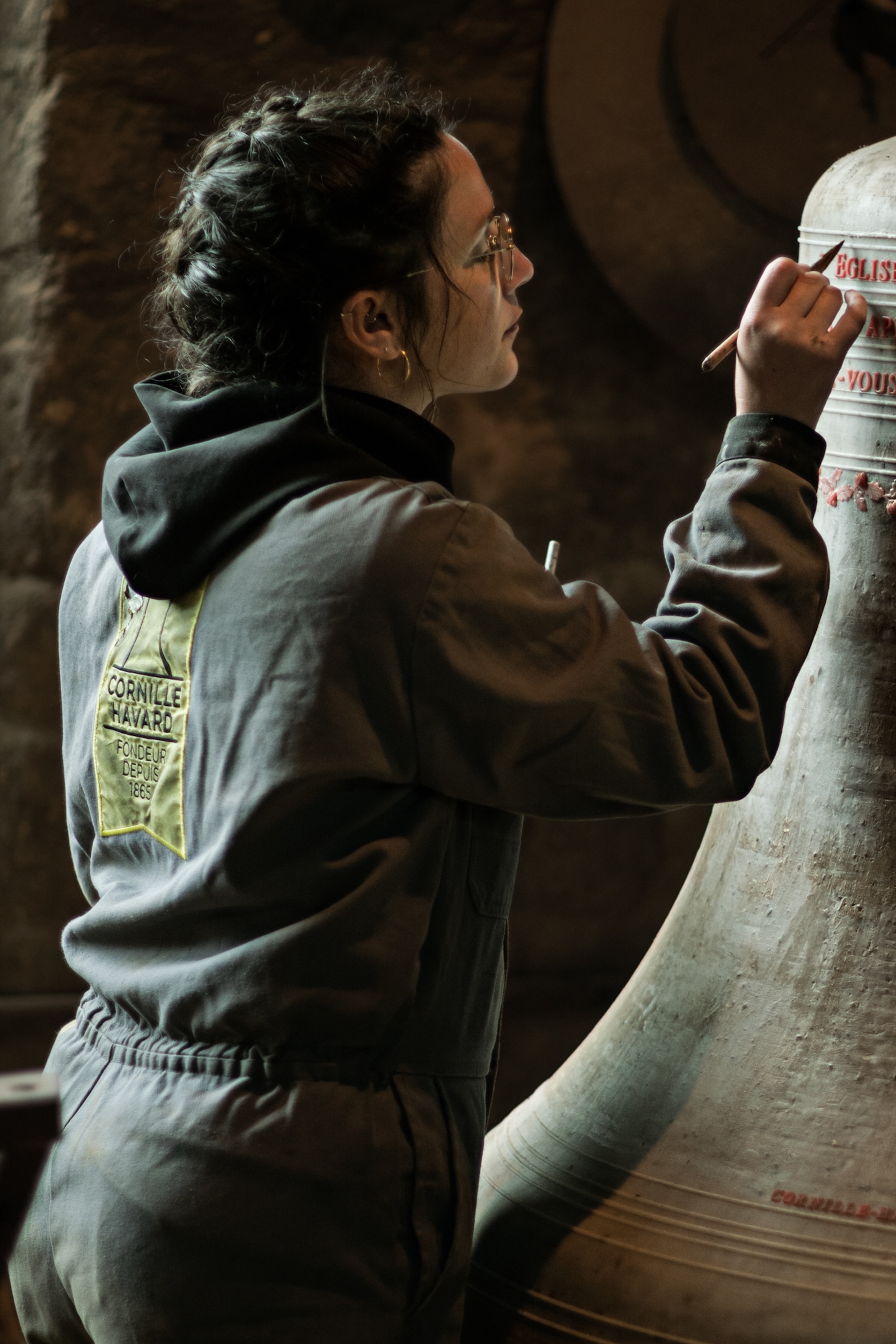

A week later, when I walked into the nave of the church, I found it hard at first to appreciate the beauty of the place. It was still a busy construction site. All around us, workers were dismantling scaffolding, stringing electrical cable, polishing the marble floor. Our small group made our way deeper into the cathedral, craning our necks to take in the soaring vaults, and crossed the transept into the choir, at the east end of the church. In the side chapels there, we could see the sumptuously refreshed wall paintings, which date to Viollet-le-Duc’s 19th-century restoration. Outside one chapel, a lone restorer knelt on the stone, her back turned to the swirl of activity. She was applying dabs of pink with a fine brush to a column painted with trefoils. In this confined space, some 250 different companies employing 2,000 workers have managed to collaborate and work in sequence over the span of the project. “It functions because people are happy and proud to be working at Notre Dame,” Jost explained.

We walked outside and then entered an elevator that carried us through the scaffolding to the top of the north transept, where we emerged in the church’s attic. We were above the ceiling vaults now, in a place not accessible to the public—in the part of the church that was most ravaged by the fire and where much of the work done over the past five years had been concentrated. Looking up, we saw blue sky through timber trusses that hadn’t yet been covered with lead roofing. We picked our way through crowded walkways to the crossing, where the two arms of the transept meet the nave and the choir. The base of the collapsing spire had plunged through the stone vaults here, then crushed the main altar on the floor below. Stonemasons had only recently closed the jagged hole in the vaults. The smell of fresh wood wafted off the oak beams and spiral stairs of the new spire.

Pressing on into the attic of the nave, we entered the new “forest” of triangular oak roof trusses. To replicate the original medieval roof, the construction workers had relied on ancient techniques. They hand-hewed the massive timbers with traditional hand axes, which had themselves been forged by hand. The beams were then fixed in a complicated lattice with pegged mortise-and-tenon joints. One of the carpenters, Hank Silver, an American who moved to France for this project, grabbed a protruding peg and hung his weight from it to demonstrate its strength.

Silver directed my eye down the nave, along the centerline of the new trusses: The line was slightly curved. That deformity had been in the medieval original, and the architects decided to replicate it. Silver explained that “it made things even more complicated for everybody.”

The new framework does include one important concession to modernity: fire protection. Fire-resistant trusses at the crossing will isolate the spire and the two transept arms from the nave and the choir, so a fire can never again race through the entire attic. Should flames break out in this space, misters distributed throughout the attic will help suppress them until firefighters can climb hundreds of stairs.

Exiting the attic at the front of the church, we spiraled up the narrow stone stairs of the south tower, passing the balcony that Viollet-le-Duc had populated with grotesque creatures. At the top of the tower, we circled around to the east. The Seine, swimmable again but still brown, rolled and sparkled in the late morning sun. From the choir, at the far end of the church, we could hear roofers hammering lead panels into place. The architect’s decision to use lead, especially after the fire had spread that toxic material all over the cathedral and even outside it, excited a public controversy. But the preservationists insisted it was more durable and impermeable than the alternatives and that the elaborate ornamentation could not be reproduced without it.

We were eye level now with the new spire. Inside and out, it’s a faithful copy of Viollet-le-Duc’s intricate creation, made from his 19th-century drawings. The one exception is the gilded brass rooster at the pinnacle, which we could see glinting in the sun: It’s Villeneuve’s own design.

The replacement was hoisted into place in December 2023. It carries inside it the relics of two Parisian saints and a scroll naming all 2,000 restoration workers. It carries symbolic meaning too: The rooster is a symbol of French identity, of hope and resurrection—and in this case, since Villeneuve gave his bird flame-shaped wings, of a cathedral rising from the ashes. The original was badly battered from its fall during the fire but was salvaged and will be displayed as a memorial of that night.

As we made our way back down from the tower, we crossed in front of the great organ, on the balcony inside the front wall. It survived the fire but had to be completely dismantled and cleaned, and for months, tuners had been calibrating the 8,000 pipes one by one. With our backs to the towering pipes, we looked out at the walls and vaults of the nave.

The stained glass glowed once again in the high windows. The soot from the fire, the lead, and the filth of the ages had been stripped from the stone walls, leaving them bright and creamy. With keystones in gold leaf and ribs delicately outlined in rich burgundy, the vaults looked impeccable. “My greatest satisfaction is that you can’t tell the vaults that collapsed and were rebuilt,” Villeneuve told me later.

There’s a lot to like about the restoration, said Leniaud, the historian. But the “brutal peeling” of the walls—latex was sprayed on them and then peeled off, in part to extract the lead—has left the stones so white that some will feel the cathedral has lost elements of its sacred character. “It will take 40 years of grime and condensation before we see the gray that the eyes appreciate,” Leniaud said.

To church officials, Notre Dame’s sacredness derives not so much from the building itself as from what goes on inside it. “The cathedral is above all a place of worship,” said Msgr. Olivier Ribadeau Dumas, “that was built for the glory of God.” Ribadeau Dumas is the rector of Notre Dame, meaning he runs the place when it’s open. He’s expecting a record 15 million to come to Notre Dame in 2025, and he doesn’t like to call them tourists; the word “visitor” is a better fit for what he anticipates they’ll experience. Once inside, he hopes, a visitor just might become a pilgrim. The redecoration is designed to facilitate that.

In addition to sculptor Bardet’s liturgical furnishings, there will be 1,500 new chairs of solid oak. With low backs, gently curved at the top, they’ll be like a calm sea that accentuates the verticality of the vaults, designer Ionna Vautrin told me. The new lighting, on the other hand, will do much more than illuminate the architecture, said light sculptor Patrick Rimoux. He’s deploying a programmable array of 1,550 LED spotlights, each of which can vary in intensity and hue according to the season and what service is being held in the cathedral. A shadowy, candlelit atmosphere on the vigil of Easter, for example, could give way to a joyous illumination on Easter morning. “What’s important is to treat the cathedral as a living place,” Rimoux said.

You May Also Like

After the fire, the clergy debated creating a little space in the choir where Catholics could attend Mass in peace, among themselves and away from the visitors. In the end they decided the opposite: All Masses will be celebrated at the main altar in the nave, with no barriers to keep tourists from wandering into the congregation. “We have prioritized the demonstration of faith over the tranquility of prayer,” Ribadeau Dumas told me.

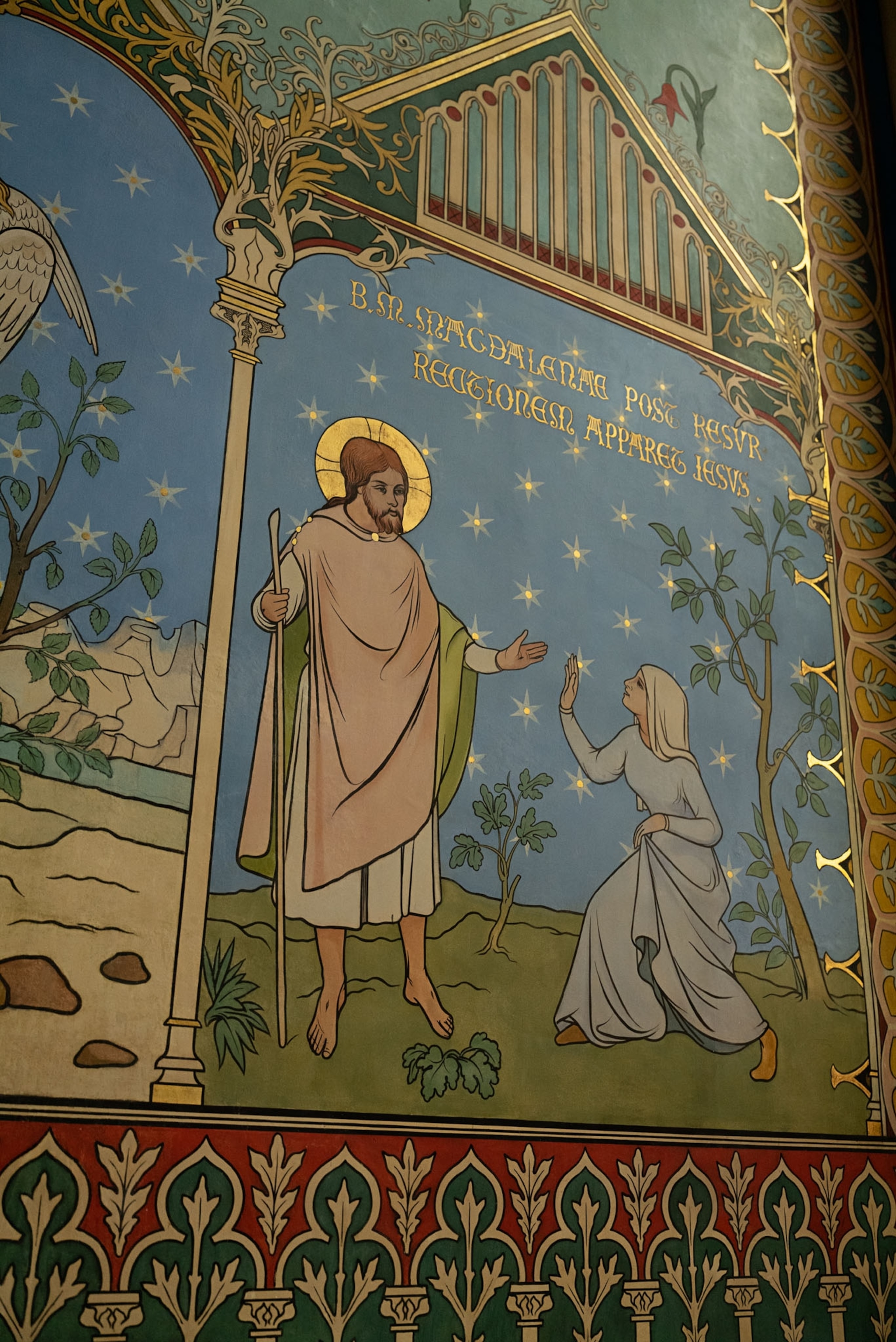

The side chapels, which had been a hodgepodge, will become a “pilgrim’s way” that gives a coherent account, in painting and sculpture, of the Catholic faith. From the entrance in the center of the west facade, visitors will move along the north aisle, where each chapel will be devoted to an Old Testament prophet; then around the perimeter of the choir, which will recount the life, death, and Resurrection of Jesus; and finally, along the south chapels of the nave, each of which will introduce a saint who embodies a particular value of the Catholic Church. A smartphone app will explain it all in multiple languages.

In the apse, at the far east end of the church, visitors will pass one of the most treasured relics in Christendom: the Crown of Thorns said to have been placed on Jesus’ head before the Crucifixion. Notre Dame never advertised its presence much. Architect Sylvain Dubuisson was commissioned to design a new reliquary to display the crown more prominently, to magnify “something that’s of an incredible humility,” he said. The artifact is a dried-out, woven wreath of rushes from which the thorns were long ago removed. Dubuisson’s solution is a 12-foot-high, eight-and-a-half-foot-wide altarpiece of cedar. At the center is a glass hemisphere, whose curved back surface will be painted dark blue but lit in such a way that the surface isn’t apparent. Looking into it will be like looking into an infinite sky. The crown will hang within it.

On the night of the fire, the crowds along the Seine had no idea what was happening inside the cathedral. We couldn’t see the firefighters racing up into the north bell tower, just in time to save it from a collapse that might have brought down the whole building. We couldn’t see the firefighters and church officials entering the burning structure to save the Crown of Thorns and other priceless artifacts, which for the past few years have been kept safe in a vault at the Louvre. By December, they will have been returned to their rightful home. As National Geographic went to press, Paris officials had still not completed their investigation into what might have caused the fire. Perhaps it was some kind of electrical short circuit.

On Saturday, December 7, the French state will return the restored cathedral to the archbishop of Paris. The archbishop will bang on the doors with his large staff, and they will open once again to the world. The great organ will wake up and blast a hymn of thanks.

When you walk into Notre Dame, the first thing you’ll see will be Bardet’s bronze baptismal font—the portal to the Catholic faith. His new altar will be visible at the crossing, under the new spire.

“In a society in which we’re often tempted by despair, reopening the cathedral is a sign of hope,” Ribadeau Dumas said. That moment should be as powerful and memorable, he said, as the sight of Notre Dame on fire was to the millions who saw it in Paris and around the planet. It will be “a kind of gust of joy that will, I hope, fill the world.”

Robert Kunzig lived in France for 12 years and returned to cover the final stages of Notre Dame’s reconstruction, building on his 2022 cover story about earlier recovery efforts. He is a former editor at the magazine.

Tomas van Houtryve is a Paris-based visual artist whose work spans photography, filmmaking and art installations. He recently released a photo book titled 36 Views of Notre Dame. He is a 2024 National Geographic Explorer.

The French government has created a special public entity to restore Notre Dame Cathedral. Follow their work on Instagram @rebatirnotredamedeparis.