Oldest Evidence of Right-Handedness Seen in Fossil Jaw

Some 1.8 million years ago, a right-handed human ancestor living in Tanzania accidentally nicked her teeth with a stone tool.

Fossils from the “handy man” of the human family tree have now provided the oldest known evidence of right-handedness in our lineage.

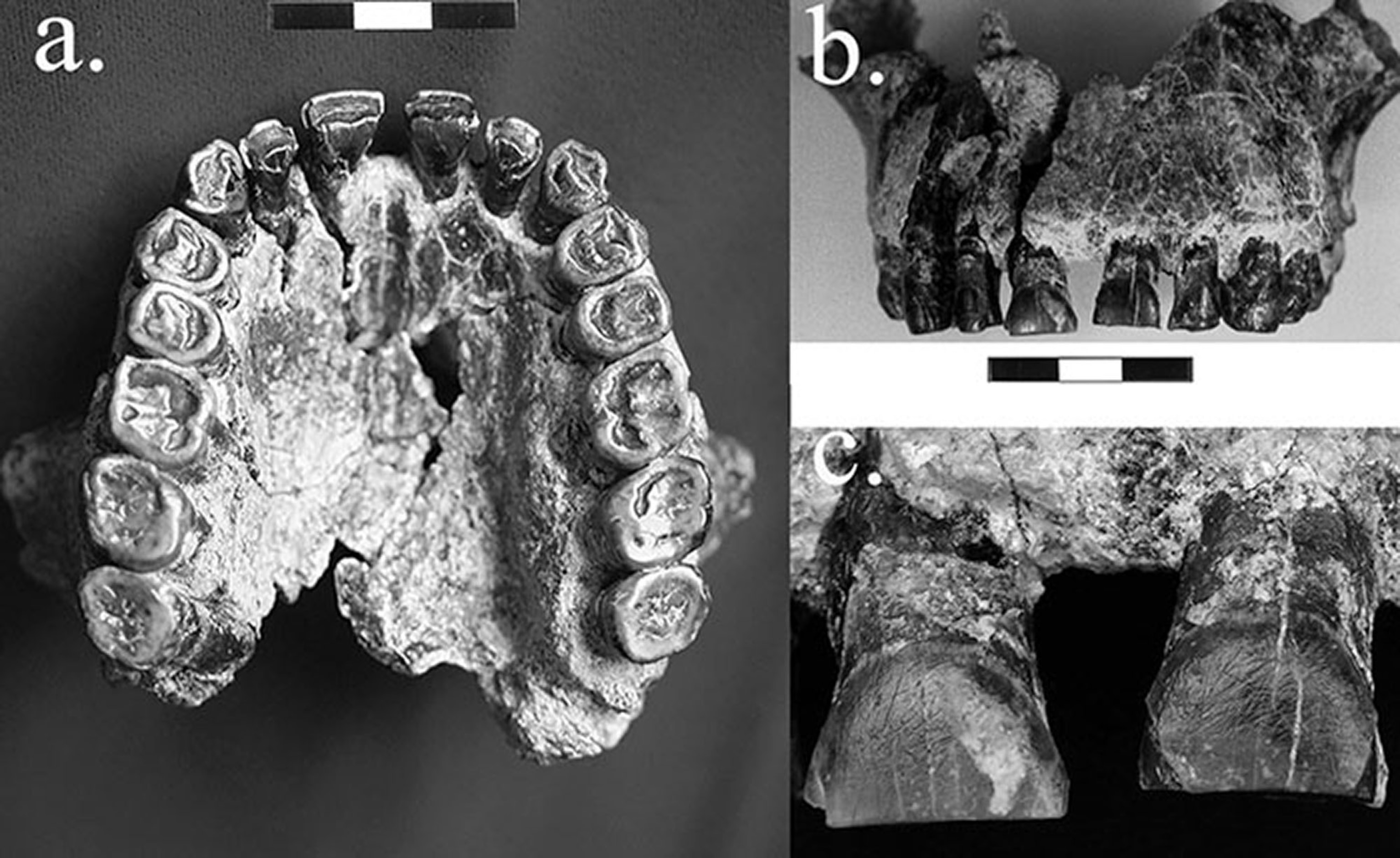

The discovery comes from a 1.8-million-year-old upper jawbone of Homo habilis, a human ancestor who lived in eastern and southern Africa from 2.4 to 1.4 million years ago. Scientists suspect the species was a regular user of stone tools, which are found in abundance around the fossil discovery site.

The jawbone’s teeth, still firmly in place, are covered in diagonal scratches that were most likely made when this Homo habilis individual, perhaps a female, accidentally nicked her teeth with a stone tool held in her right hand.

While the Homo habilis jawbone is a sample size of one, its very existence says that scientists could use the species’ teeth to learn more about ancient humans’ brain organization.

Today, about 90 percent of humans are right-handed, a skewed ratio that’s associated with how much the two hemispheres of our brain divide up processing different tasks. Intriguingly, the human brain’s left hemisphere not only controls the body’s right side, but it also contains the centers that control language.

“There’s an association between right-handedness, cerebral lateral asymmetry, and language—all fit together in a package,” says anthropologist David Frayer of the University of Kansas. Frayer led the study of the Homo habilis jawbone, published online last week in the Journal of Human Evolution.

This relationship seems to hold across primates: Neanderthal remains, for instance, show that they were also overwhelmingly right-handed, while chimpanzees are about three-fifths right-handed, by some estimates. Bonobos show no preference for either hand.

Getting Into the Groove

The Homo habilis fossil is from Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge, one of the richest fossil sites containing ancient hominin remains. The specimen is more than 1.3 million years older than the next oldest evidence for handedness in humans, a set of Homo heidelbergensis jawbones and teeth first described in 2009.

Counterintuitively, scientists often have to rely on ancient teeth to determine what ancient hominins were doing with their hands.

Experiments with modern humans wearing mouth guards suggest that if a person holds an object taut between her mouth and nondominant hand—a large hunk of food, perhaps, or maybe a hide—and then cuts it with a stone tool in her dominant hand, the tool occasionally nicks the person’s teeth.

If a person is right-handed, those grooves run from the upper left to the lower right of the tooth surface.

Sure enough, when Frayer and his colleagues examined the Homo habilis jawbone, the teeth exhibited these diagonal grooves, suggesting that 1.8 million years ago, someone in what’s now Tanzania may well have been a right-hand woman—or a right-hand man.

“Teeth are incredible because they preserve their chemistry, growth, and development,” says Debbie Guatelli-Steinberg, an anthropologist at the Ohio State University who wasn’t involved with the study. “You can extract a lot from them—no pun intended.”

Frayer and Guatelli-Steinberg both point out, however, that one set of teeth cannot tell the whole story.

“For this to really speak to the human trait—a predilection of right-handedness—we need to get some idea of the proportion of individuals who were using their right hands,” says Guatelli-Steinberg.

Frayer says that he hopes the new study will help to solve that problem by inspiring other researchers to examine additional Homo habilis teeth for the telltale grooves.

“There are [other] incisors and canines that people could look at, [and] almost for sure this isn’t an isolated case,” says Frayer. “It’d be a good dissertation topic.”