The real history of the Borgia family and their cursed 'black legend'

Not unlike many of the Renaissance families of Italy, the Borgias were power hungry, corrupt, and self-indulgent. But their bloodline produced two popes—are they worthy of this notorious legacy?

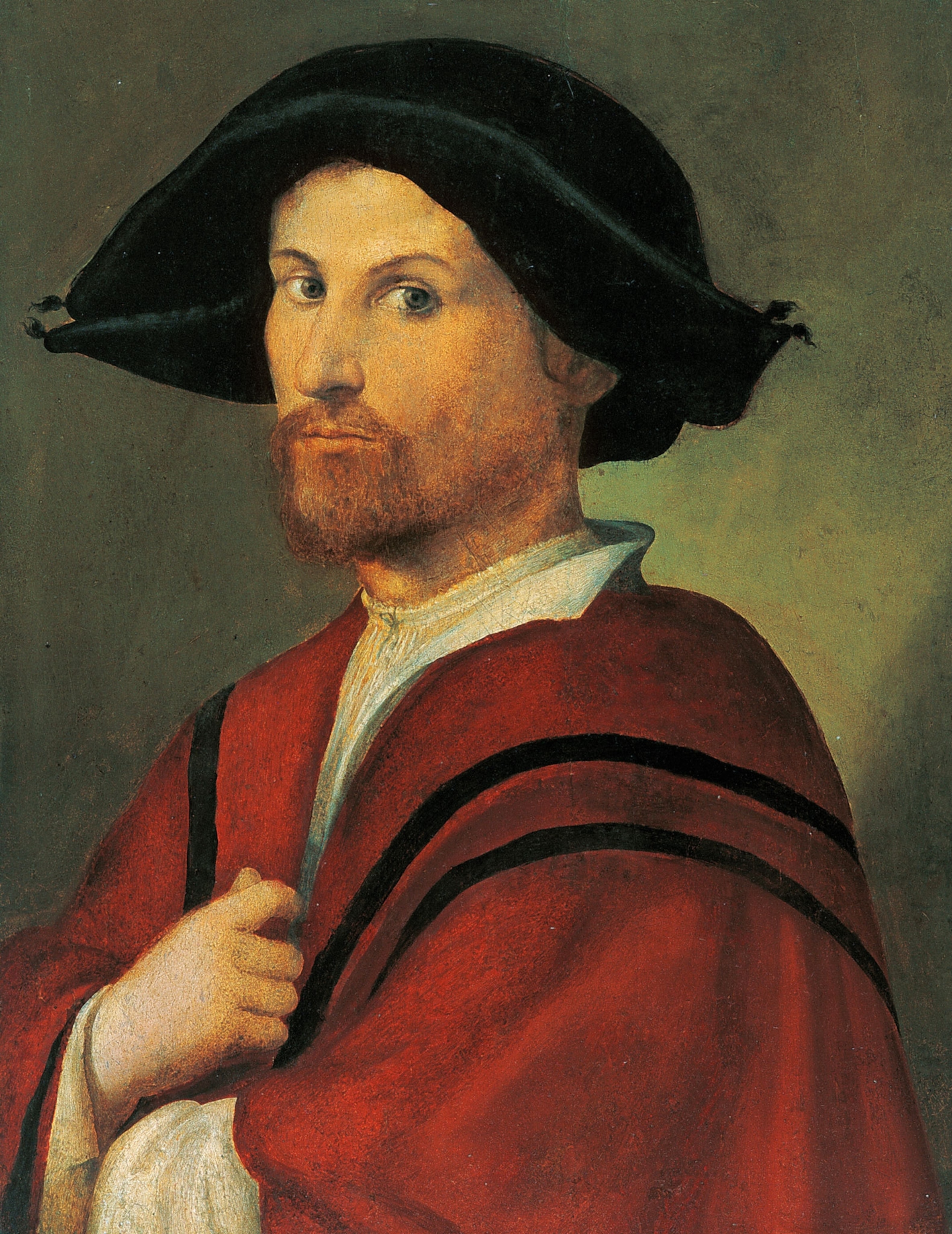

In the searing heat of Rome, August 1492, a large and lavish ceremony took place to crown a new pope who had bribed his way into office: the Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia of Valencia, Spain, known from then on as Alexander VI. At 60 years old, the new pope was an imposing man with exquisite manners and an affable charm. He had served as dean of the College of Cardinals and vice-chancellor of the Church for five papacies, surpassing all other prelates in authority, knowledge, experience, and influence.

But Rodrigo was a man of the secular world too. He had already fathered a boy and two girls by the time he met Vannozza Cattanei, his lover for more than three decades. With Cattanei, he had four more children—Cesare, Juan, Lucrezia, and Goffredo–each of whom he openly claimed and all of them brilliant and controversial in their own right. They were star players in the scandalous events that surrounded the Borgia family. The highly unfavorable “black legend” was created by their enemies, and although much of it was built on nothing more than malicious gossip, it continues to fascinate.

A loving father

Rodrigo was a devoted and attentive father. But plans for his children combined affection with pragmatism. Each family member had to play their role in the joint project that was increasing the existing power, influence, and wealth of the House of Borgia. In 1485 Rodrigo bought the duchy of Gandía in eastern Spain from King Ferdinand II of Aragon, and promised marriage between his firstborn son, Pier Luigi, and the king’s first cousin, María Enríquez de Luna.

This laid a solid base in Rodrigo’s native kingdom of Valencia (he was born in Xàtiva), from where he could establish the secular power of the Borgia family. Three years later, Pier Luigi died, and his half brother Juan became the Duke of Gandía. Juan would also marry Pier Luigi’s betrothed. By this time, Rodrigo had already lost one daughter and the other had been married to a nobleman from Rome, so he concentrated all his expectations and paternal love on the children he had with Cattanei.

Keeping it in the family

Cesare, Juan, Lucrezia, and Goffredo had spent their early years with their mother in a house located next to the Borgia palace, the most beautiful and sumptuous residence in Rome. Notorious for his extreme wealth, Rodrigo had been severely rebuked by Pope Pius II for his indulgence with mistresses. Despite Cattanei’s successive marriages also complicating the picture, the Borgia-Cattanei dynamic was, for many years at least, intense and affectionate. By the time Goffredo, their youngest child, was born, the romance between Rodrigo and Cattanei had cooled. Still, their relationship remained amicable.

Rodrigo’s papal election significantly impacted the whole Borgia family, bringing an increase of power, wealth, and enemies. He was immensely proud of his children, who by then were all in their prime. He loved their youth, their grace and beauty, their lively wits, good manners, and joy. He wanted them nearby so he could enjoy their company and show them off. He installed Lucrezia in the Palazzo Santa Maria in Portico, which was attached to St. Peter’s Basilica, and housed his sons either in the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace (the pope’s residence) or close by.

(St. Peter's Basilica contains his tomb... right? Why there's still some doubt.)

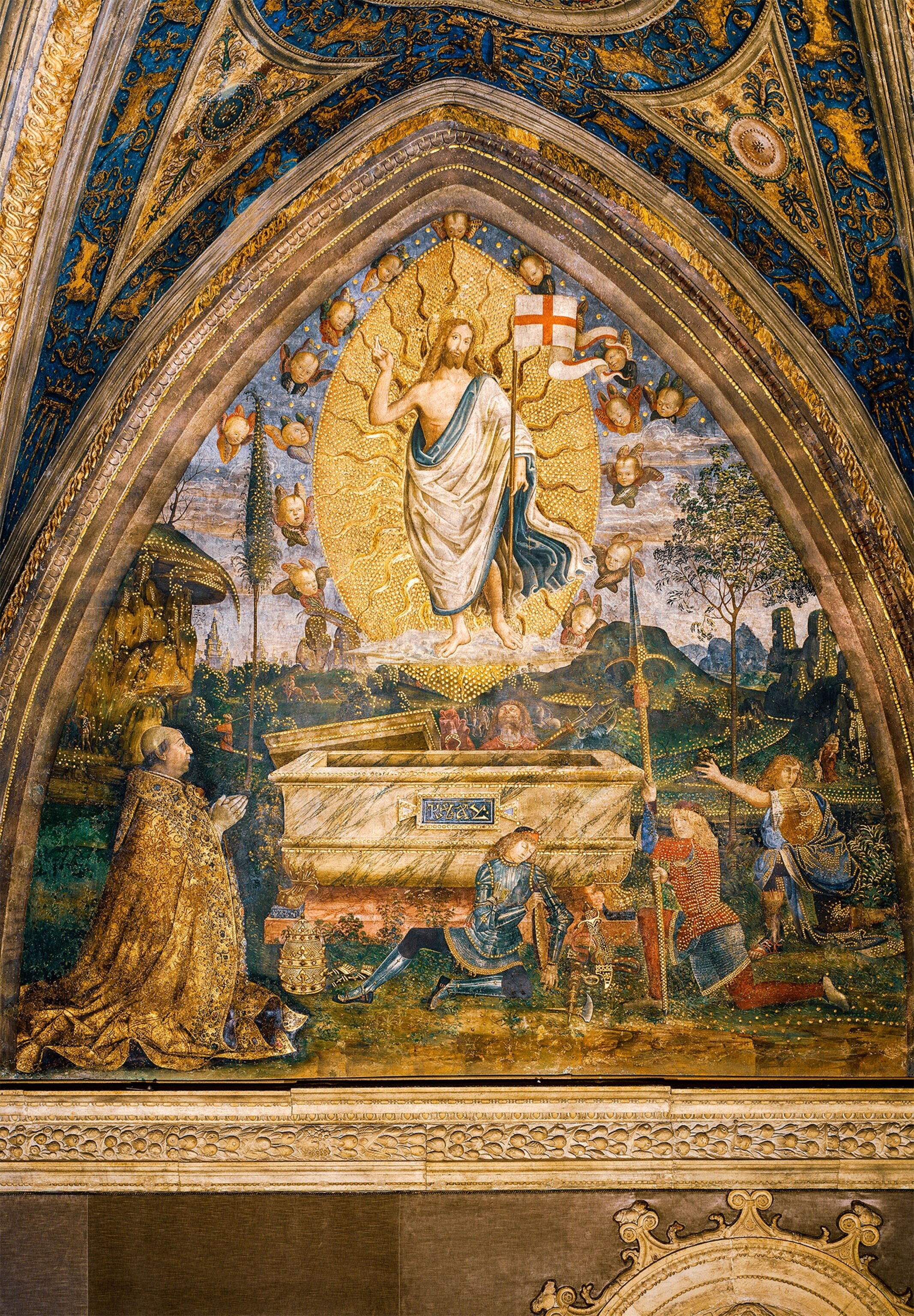

The so-called secret rooms of the Borgia Apartment, intended for the pontiff’s private use, became the family meeting place. It was here where Lucrezia celebrated her first marriage, among hundreds of guests, as well as the party for her second wedding. For one of the occasions, the rooms were lavishly decorated, with a fountain and entertainers dressed as animals emerging from foliage to dance with guests. One afternoon, a ceiling of one room collapsed onto the throne of Alexander VI while he waited for his children. (The strength of the canopy that covered the seat saved his life.) In another nearby chamber, Alfonso of Aragon, Lucrezia’s second husband, was murdered. The home of the Borgias was a place of happiness and misfortune for 11 years.

Mixing politics and family

Rodrigo’s accession to the papal throne introduced a new element to his plans: The careers and marriages of his children would need to do more than simply satisfy the Borgia family’s personal interests. Nepotistic appointments were quite common for the Church. Rodrigo was appointed a cardinal when his uncle reigned as Pope Calixtus III. Likewise, Pope Alexander VI bestowed his son Cesare with the same appointment. Any marital match would also shore up the Papal States, the Church’s dominions on Italian soil, which were under threat from France and the Catholic Monarchs of Spain.

Between 1493 and 1494, Pope Alexander VI sealed three important alliances. Juan, Duke of Gandía, was married to María Enríquez de Luna, a cousin of Ferdinand II’s. Lucrezia was married to Giovanni Sforza, a relative of the powerful Duke of Milan. And Goffredo was married to Sancha of Aragon, the illegitimate daughter of King Alfonso II of Naples (also a relative of Ferdinand II’s). Despite the pope’s strong opposition, the French king invaded Italy in 1494 with the help of the Duke of Milan. After three years, this resulted in the annulment of Lucrezia’s marriage to Sforza, and she subsequently married Alfonso of Aragon, Sancha’s brother. The union reinforced the pope’s Neapolitan alliance.

During this turbulent period, political events led Cardinal Cesare to abandon his ecclesiastical career and, in agreement with his father, marry a sister of the king of Navarre, a relative of the French monarch. This alliance clashed with the interests of the king of Naples and his relatives, the Catholic Monarchs, Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon. Tension arose within the Borgia family, as Lucrezia and Cesare found themselves, through their spouses, on opposing sides of the war until Lucrezia’s husband was murdered in 1500. The strain was ultimately assuaged by Lucrezia’s third marriage to the future Duke of Ferrara, a match deemed acceptable by the whole family.

(Inside the decadence of Casanova’s Venice, a pleasure capital.)

Father and children

The children of Alexander VI did not question their father’s decisions. He was the source of their power and wealth. They owed him obedience both as a parent and as the supreme pontiff. But Alexander’s behavior could be troubling, and it took a toll on his children and their relationships with each other. Although he loved them all, the pope did not hide his preferences. Goffredo, the youngest, was not the favorite. More than once, Alexander even questioned whether Goffredo, who was timid by nature, was actually his son. Alexander’s relative detachment from Goffredo led to heated confrontations between the pope and Goffredo’s wife, Sancha. While Goffredo tended to keep his head down and obey his father’s commands, she wasn’t one to bite her tongue.

Juan, on the other hand, was adored by the pope. At the request of the Catholic Monarchs, Juan was sent to Spain to be invested as Duke of Gandía and to seal the marriage arranged for him with Ferdinand II’s cousin. Alexander prepared an even more splendid future for Juan on Italian soil. He showered him with titles, honors, territories, and wealth. And Juan, though he didn’t always follow his father’s advice, knew how to talk him round. But in 1497, when Juan returned to Rome, disaster struck. He was stabbed to death by unknown assassins and thrown into the Tiber River. Alexander’s desolation was absolute: “If we had seven papacies, we would give them all to restore him to life,” he declared, weeping before the consistory.

Who murdered the Duke of Gandía?

As cardinal, Cesare from the beginning offered the pope firm support in affairs of both Church and state. An ambassador Gianandrea Boccaccio wrote of Cesare, “He is a man of great talent and of an excellent nature; his manners are those of the son of a great prince...” Perhaps his father saw in him the potential for a third Borgia pope. In any case, Alexander did not immediately give in to Cesare’s repeated requests that he be allowed to abandon his own ecclesiastical career, for which Cesare claimed he felt no vocation. The pope only accepted Cesare’s resignation as cardinal a year after Juan’s death.

Cesare recognized his father as a great master in the art of politics and the changing alliances that characterized the time. They had several shared objectives, but Cesare was aware that given his father’s age and failing health, time was running out. As commander of the papal army, Cesare conquered cities in an attempt to carve out a Borgia state. Even his allies despised his growing power, and after his father’s passing, Cesare struggled to maintain control without papal support.

(He was a Founding Father. His son sided with the British.)

Luxury apartments

Lucrezia, the most favored

Among all his children, the pope most favored Lucrezia, the jewel of the family, for her beauty, sweet nature, and refinement. There was a strong bond of affection between father and daughter. Lucrezia’s first husband was Giovanni Sforza, a relative of the Duke of Milan. That marriage failed on not only a personal level but also a political one. The marriage ended in annulment, and for Lucrezia there was a bitter epilogue. Sforza insinuated that she had engaged in an incestuous relationship with her father. Rumors spread to implicate her brothers too. Although the claim was refuted time and again, it still lingered.

The black legend of the Borgias

Despite their familial affection, Lucrezia soon discovered that her father had as much capacity to hurt her as he had to love her, and it would be impossible to find peace so long as he could interfere in her life. So, after the murder of her second husband, Alfonso of Aragon, she married for a third time, to Alfonso d’Este, heir to the duchies of Ferrara, Modena, and Reggio. This allowed her to move far from Rome. Aware of her reasons for leaving, and of the union’s convenience for the entire family, her father accepted the separation. Of the pope’s regard for his daughter, the Duke of Ferrara’s secretary remarked, “His Holiness loves her more than any other person of his blood.”

(While Napoleon conquered nations, his sister conquered hearts.)

Sibling rivalries

Wherever the Borgia-Cattanei met, laughter, gallantry, wit, and music abounded. But it wasn’t all smooth sailing. Some of the natural squabbles among siblings hardened into bitterness. Lucrezia was, in a way, the one who held them together. Goffredo was particularly close to Lucrezia: They went everywhere together, and she was protective of him. They grew even closer when Lucrezia married Alfonso of Aragon, the brother of Goffredo’s wife, Sancha. Lucrezia and Sancha were great friends and neither the failure of Sancha and Goffredo’s marriage nor the death of Alfonso broke the bond of friendship between the two sisters-in-law. It was Goffredo who protected Lucrezia and Alfonso’s two-year-old son, Rodrigo, during the violent acts unleashed in Rome after the death of the pope. Little Rodrigo’s father, Alfonso of Aragon, was already dead by this point.

But the brother for whom Lucrezia had the most affinity was Juan. Between Juan and Cesare, however, the relationship was strained. Alexander had maneuvered for Juan to receive all sorts of titles and territories, believing that this was in the best interest of the wider family. Meanwhile, Cesare, despite outshining his brother intellectually, had been forced to follow an ecclesiastical path that he hated. Perhaps Cesare considered himself more qualified than his brother to become a great prince. That perception was emphasized when Juan returned to Rome and demonstrated mediocre skills on the battlefield. Though Cesare lacked Juan’s titles, his influence in the political and ecclesiastical realms went beyond that of the duke’s power. In fact, as the pope’s cardinal legate, Cesare was preparing to crown the new king of Naples, Frederick II. It was a level of authority that was difficult to surpass.

Malicious rumors circulated that both Cesare and Juan were vying for their sister-in-law, Sancha of Aragon. It is impossible to know whether or not there was any truth to the gossip. Juan did have a reputation for being a womanizer, but the story could also have been an invention of the so-called black legend. The later accusations that Cesare murdered Juan because of sexual jealousy over Sancha are also hard to prove. Such gossip, however, worked to obscure an obvious political motive for the crime. Juan had achieved enormous power on Italian soil, and his death dealt a severe blow to the power of the House the Borgia in Italy and the kingdom of Valencia. Juan’s heir was not yet three years old, showing the vulnerability of the pontiff.

(The alleged affair that started a century-long war.)

Lucrezia and Cesare

The relationship between Cesare and Lucrezia lurched between affection to rivalry. At one point, their respective marriages placed them in rival camps: Lucrezia’s second husband Alfonso of Aragon was the son of the new king of Naples, while Cesare married a sister of the king of France. As the French and Neapolitan monarchs prepared to go to war, the pope maintained his alliance with Naples.

The antagonism between Cesare and Lucrezia’s short-lived second husband, Alfonso of Aragon, was palpable. And, in the summer of 1500, while convalescing from a serious attack, Alfonso was murdered in his bed by Cesare’s hit men. Cesare alleged that Alfonso had attacked him first by shooting at him with a crossbow bolt from his sickroom. The details of what really happened are shrouded in mystery. Shortly after, Alexander VI switched his allegiances to France.

For Lucrezia, the murder of her husband was difficult to forgive. And yet, when Cesare was in trouble after the death of Alexander, she helped him with weapons and money. By that time she was the Duchess of Ferrara, and was able to intercede on his behalf, appealing to Ferdinand II, who was holding him captive. Cesare managed to escape and reach the kingdom of Navarra, where he died in Viana fighting at the head of the Navarrese army. This deeply affected Lucrezia because she loved him like a mother.

The Borgias tended to form a united front in both their successes and failures. Their behavior, though similar to that of other noble households of the era, was scrutinized intently, and enemies of the family and the papacy seized upon and distorted any unusual detail as they laid the groundwork for the black legend of the Borgias. Even as historical evidence contradicts the legend, this “soap opera” has penetrated deep into popular imagination, and there it has remained.