Was Queen Victoria the first influencer? How the ‘media monarch’ shaped the modern world

From white wedding dresses to Christmas trees, Victoria’s personal choices became global trends—long before the age of social media.

Walk through the streets of the United Kingdom, and you’ll see Queen Victoria’s name everywhere, from rail stations to parks, pubs, and a line on the London Underground. The reason? Between 1837 and 1901, Victoria reigned over a rapidly changing world—one that saw the rise of trains, telegraphs, and electric light. But she wasn’t just a ruler. She was a cultural force.

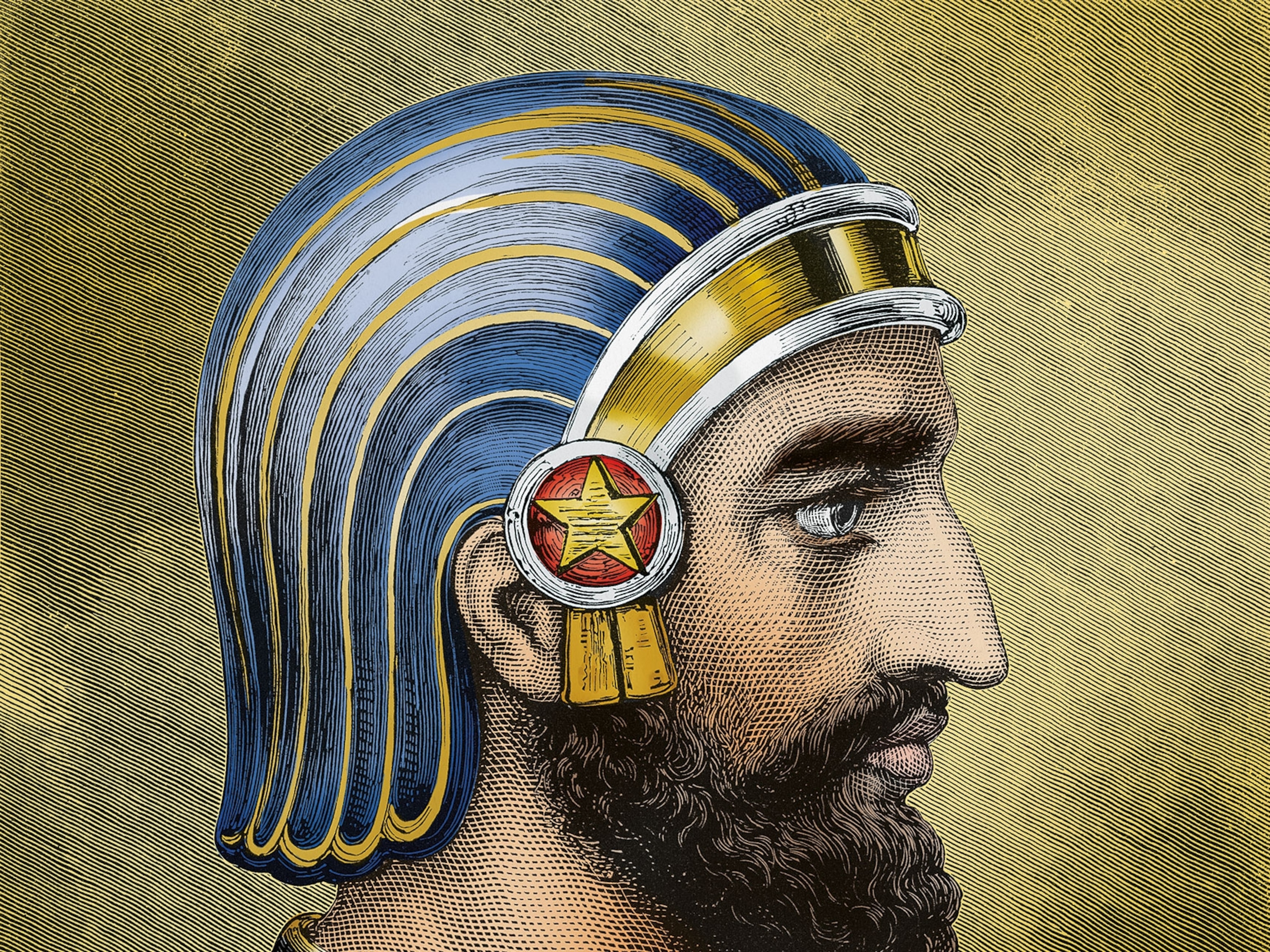

Victoria was what historian John Plunkett has called the “first media monarch,” one who was squarely in the public eye thanks to an expanding media culture. Images of the queen appeared in newspapers, prints, and postcards, making her more visible to her subjects than any monarch before her.

From the popularity of white wedding dresses to Christmas trees, Victoria set trends that still resonate today. Here’s how this 19th-century queen became an accidental influencer long before social media.

The wedding dress trend that never faded

Long before she wore a crown, Victoria was captivated by clothing. “She loved fashion,” says fashion historian Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell. As a child, Victoria would “go to the ballet or the opera and take notes on the costumes, then come home and draw them. Then she and her governess would use the drawings to make outfits for her dolls.”

When Victoria ascended the throne at 18 years old in 1837, her sartorial choices quickly became the benchmark for women at court—and beyond.

“She didn’t really reinvent fashion,” says Chrisman-Campbell. “Her style was widely influential precisely because it was conservative and didn’t offend middle-class values.”

Arguably her greatest fashion contribution is also the most enduring. In 1840, the 21-year-old Victoria married Prince Albert, the love of her life. For the ceremony, she eschewed royal robes and instead wore a gown like many young brides of the time. But one detail made her choice revolutionary: the color.

“Most brides wore their best dress regardless of color,” Chrisman-Campbell explains. In Victoria’s case, she opted for a white dress, a move that helped make white the default color for bridalwear.

“White was already known for wealthier brides,” says Sally Goodsir, curator of decorative arts at the Royal Collection Trust, “ but it simply became more popular after this wedding.”

How Christmas trees became a holiday staple

Victoria’s influence stretched beyond fashion—her family’s holiday traditions helped shape how Christmas is celebrated today. One of their most enduring contributions? The Christmas tree.

Though Victoria’s German-born grandmother Queen Charlotte had introduced decorated Christmas trees to Britain decades earlier, it was Victoria and her German-born husband who made them a holiday staple.

(Why do we have Christmas trees? The surprising history behind this holiday tradition.)

Victoria and Albert specifically displayed fir trees, which Goodsir speculates may have been sourced at Windsor Great Park. “Within their apartments, individual Christmas trees for the senior members of the family as well as each of their eventual nine children would be laid on tables, with unwrapped gifts arranged underneath each tree,” she says. “The trees were decorated with brightly colored paper chains and drops, as well as lit candles and sweetmeats.”

Goodsir adds that images of the royal family with their Christmas tree appeared in the Illustrated London News in 1848, which helped the tradition spread.

Turning Scotland into a must-visit destination

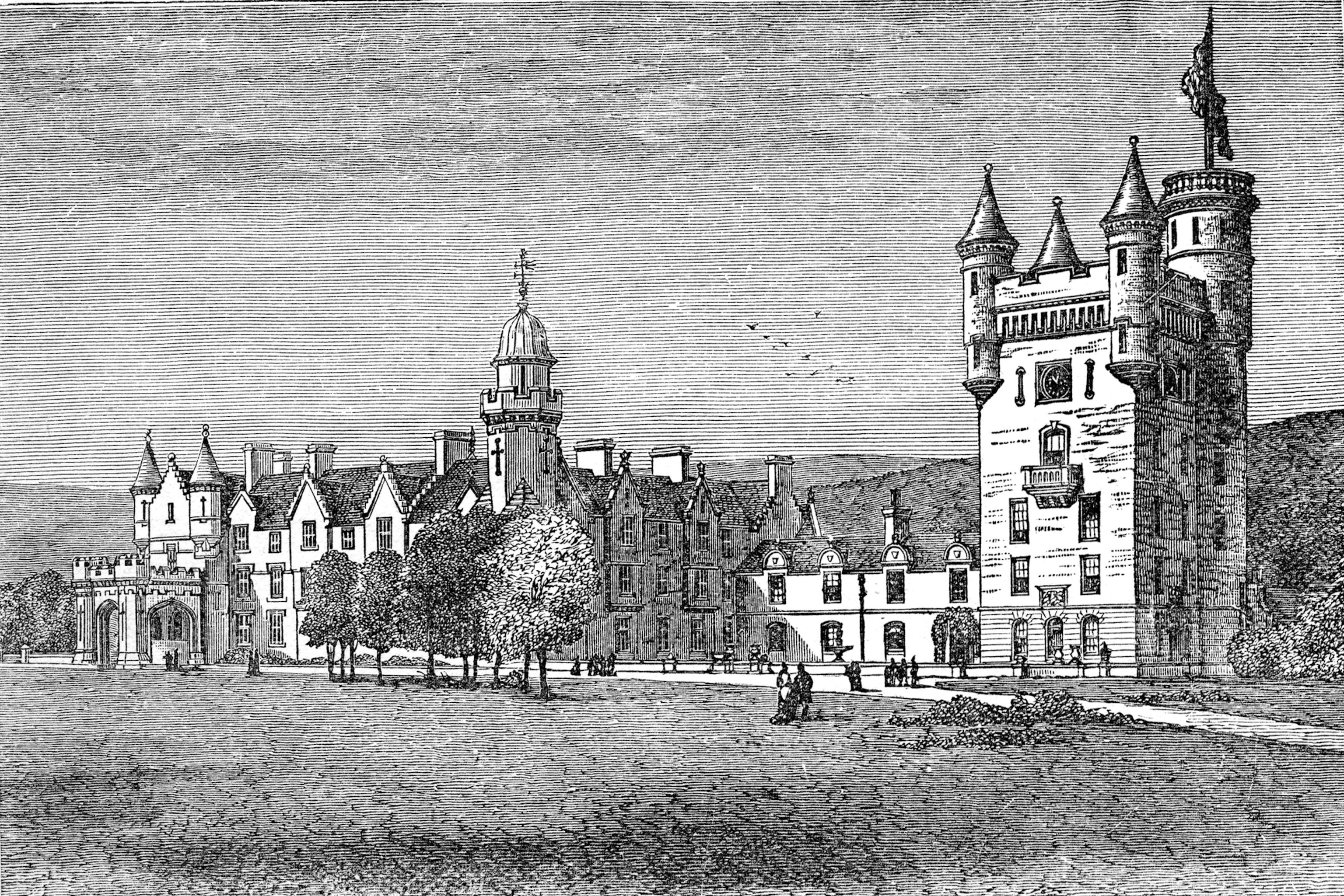

One of Victoria and Albert’s favorite places was Scotland, which, thanks to a growing network of railroads across Britain, was becoming easier to access.

Their love of Scotland helped draw throngs of tourists, eager to follow in their footsteps, to the region. After Victoria and Albert completed a royal tour there in 1847, for instance, a steamship company created an itinerary to take tourists along their route in western Scotland.

Victoria and Albert visited Scotland so frequently that they decided to put down roots there. In 1852, they purchased Balmoral Castle, an estate in the Highlands. As a result, a Scottish estate became a coveted item among Britain’s moneyed class.

A royal endorsement that changed childbirth

Victoria’s impact wasn’t limited to leisure. As a mother of nine, she also played a surprising role in changing attitudes toward childbirth. She loathed being pregnant, describing it in 1858 as feeling “pinned down” and having “one’s wings clipped.”

Few things could relieve Victoria’s discomfort with pregnancy, but pain during labor could be managed thanks to a revolutionary new approach: the use of chloroform, an anesthesia available from 1847.

Chloroform for childbirth sparked fierce controversy within the medical community. Some physicians feared it would make women unresponsive during childbirth, while others insisted that labor pains were the natural cross women had to bear.

These debates didn’t deter Victoria. When she went into labor with what would be her eighth child in April 1853, she did so with the help of chloroform. The queen seemed to have responded well to it, and she noted in her journal that “the effect was soothing, quieting, and delightful beyond measure.”

Victoria’s experience with chloroform inspired other women to use it, promoting the idea that childbirth didn’t have to be physically painful. In this way, Victoria empowered women to gain more agency over their own medical care.

Mourning became a lifelong ritual

Victoria’s approach to childbirth gave women new options, but in her own life, loss proved inescapable. When Prince Albert died in 1861, the queen’s mourning set a new standard for grief in the Victorian era.

“Following Prince Albert’s death in 1861, she had the room in which he died kept as it was and added to it a selection of jewelry and mementoes,” says Goodsir.

Victoria’s mourning was extreme, even for her time. “Elaborate mourning etiquette was normal at the time, but many widows gave it up within a few years, or at least replaced head-to-toe black with gray or lavender,” Chrisman-Campbell says. “Victoria wore black and curtailed public activities for the rest of her life with relatively few modifications.”

Still, there were limits to the queen’s influence. After years of remaining out of the public eye, her subjects began to disapprove of her absence. Eventually, she resumed public duties—but never abandoned her widow’s weeds.

Her grief reconfirmed society’s commitment to mourning etiquette, including wearing black attire. “There is no doubt that the influence of the widowed Queen was one of the prime reasons for the widespread use of mourning etiquette and dress in the second half of the 19th century,” wrote historian Lou Taylor.