Who was Rosa Parks? Meet the woman who changed the course of history

The activist’s refusal to give up her seat to a white passenger on a segregated bus in Alabama helped fuel the Civil Rights Movement.

The middle-aged seamstress was an unlikely civil rights hero. But when Rosa Parks refused to give up a seat on a segregated bus in 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, she became a titan in the struggle for racial equality. Parks’ modest looks and quiet demeanor belied her true identity: that of a fierce, disciplined, and committed civil rights activist.

A force to be reckoned with, Parks contributed to the movement long before—and long after—her act of protest on that bus. Here’s what to know about the woman whose simple act of civil disobedience, and lifelong commitment to racial equality, helped push forward the struggle for civil rights in the United States.

Rosa Parks’ early life

Born Rosa Louise McCauley in Tuskegee, Alabama on February 4, 1913, to a carpenter father and teacher mother, Rosa was largely raised by her maternal grandparents on their farm. Daily life involved devout church attendance, farm chores, and later, an education at the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls. But the racism of the Jim Crow South surrounded Parks’ life, with segregationist policies preventing Black citizens’ full participation in society and strictly separating life along racial lines.

(Learn how Jim Crow laws created ‘slavery by another name’.)

As she recalled later in her autobiography, one of her earliest memories was of the terror inflicted by the local branch of the Ku Klux Klan and a vigil with her grandfather, who stayed up all night ready to defend his farm against invaders. Racial discrimination continued as she later recalled bullying by local white children.

Financial difficulties and family illness during the Great Depression forced Parks to drop out of school at age 16. She became a domestic worker and a seamstress, marrying Raymond Parks in 1932 and eventually earning her high school diploma—a rare accomplishment for a young Black woman at the time.

Rosa Parks’ contributions to the civil rights movement

By the time Parks famously refused to give up a seat on a segregated bus in 1955, she was a well-known figure in the struggle for racial equality.

Parks’ husband, Raymond, was a charter member of the NAACP branch in Montgomery, Alabama. He worked to support the defense of the Scottsboro boys, nine Black teens sentenced to death after being falsely accused of raping two white women aboard an Alabama train. In the 1940s, Rosa became active in the NAACP too, leading the youth division of the Montgomery branch and serving as secretary.

In September 1944, the rape case of Recy Taylor galvanized Alabama and Parks. Taylor was a young Black woman abducted and raped by a group of six white men. For Alabama during Jim Crow, Taylor’s story was a symbol of the danger many Black women in the South faced at the time. The Montgomery NAACP sent Parks to investigate the crime, and she helped found a nationwide campaign for justice. But despite the confession of one of her assailants, multiple all-white grand juries refused to prosecute the men.

Parks’s attempt to get justice for Taylor may have failed, but it put her on an activist’s path. She began investigating other cases of discrimination and crime affecting Black Southerners for the NAACP, becoming the organization’s state secretary.

Parks’ impact on the Montgomery Bus Boycott

In 1955, the NAACP was on the lookout for a test case to challenge segregation on public transportation in Alabama. Others had attempted to defy the Montgomery bus system’s seating arrangements, which mandated that Black passengers ride near the back of the bus or give up seats in more favorable spots to white riders. But according to Parks, her decision to challenge a bus driver’s order to cede her seat to a white passenger on December 1, 1955, was a spontaneous one.

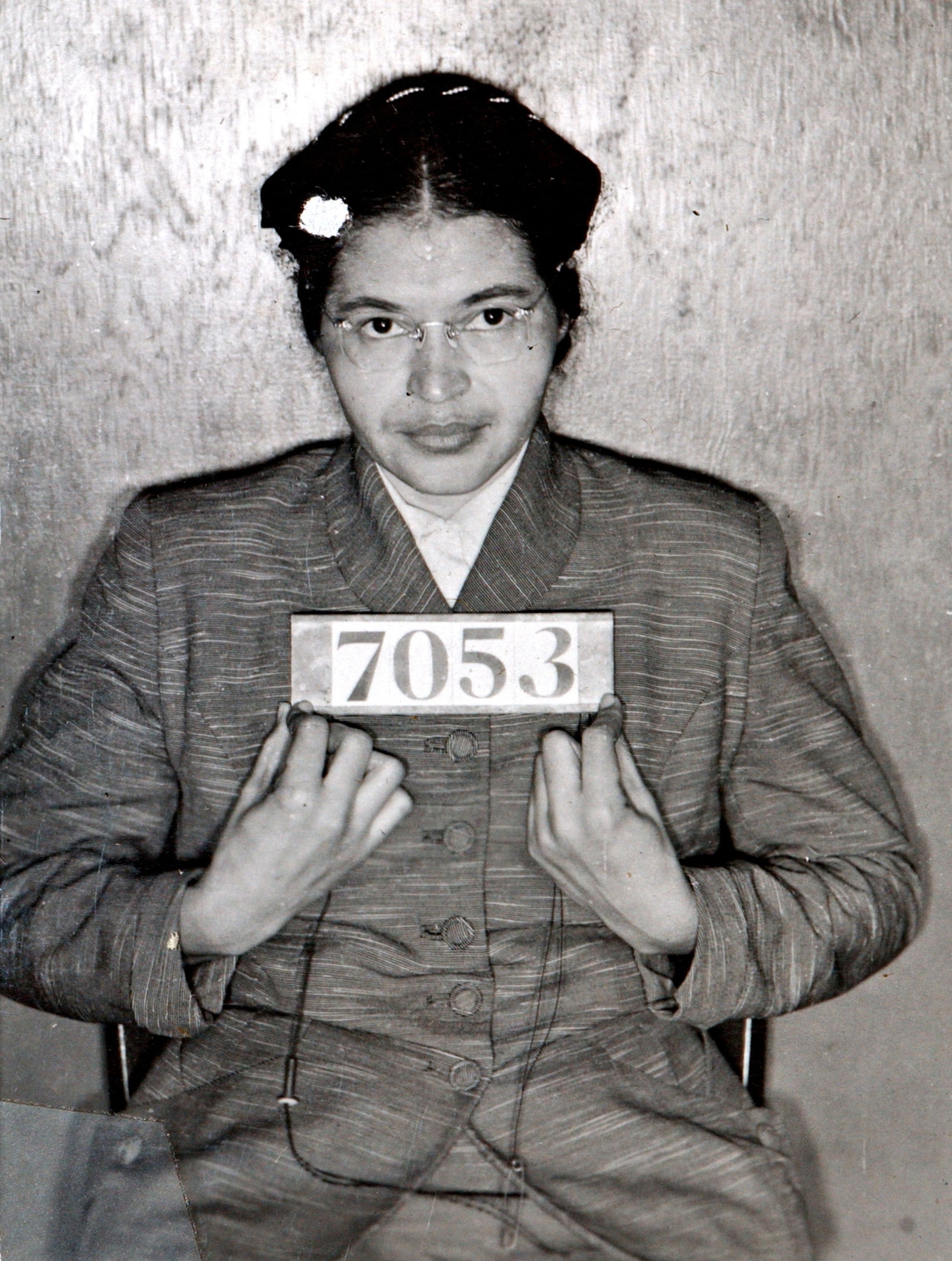

That evening, an exhausted Parks sat down on a crowded bus on her way home from work. When told to give up her seat for a white man, she simply refused. As a result, she was arrested for disorderly conduct and briefly jailed.

“I had been pushed around for all my life and felt at this moment that I couldn’t take it anymore,” she wrote in 1955. “There is just so much hurt, disappointment, and oppression one can take.”

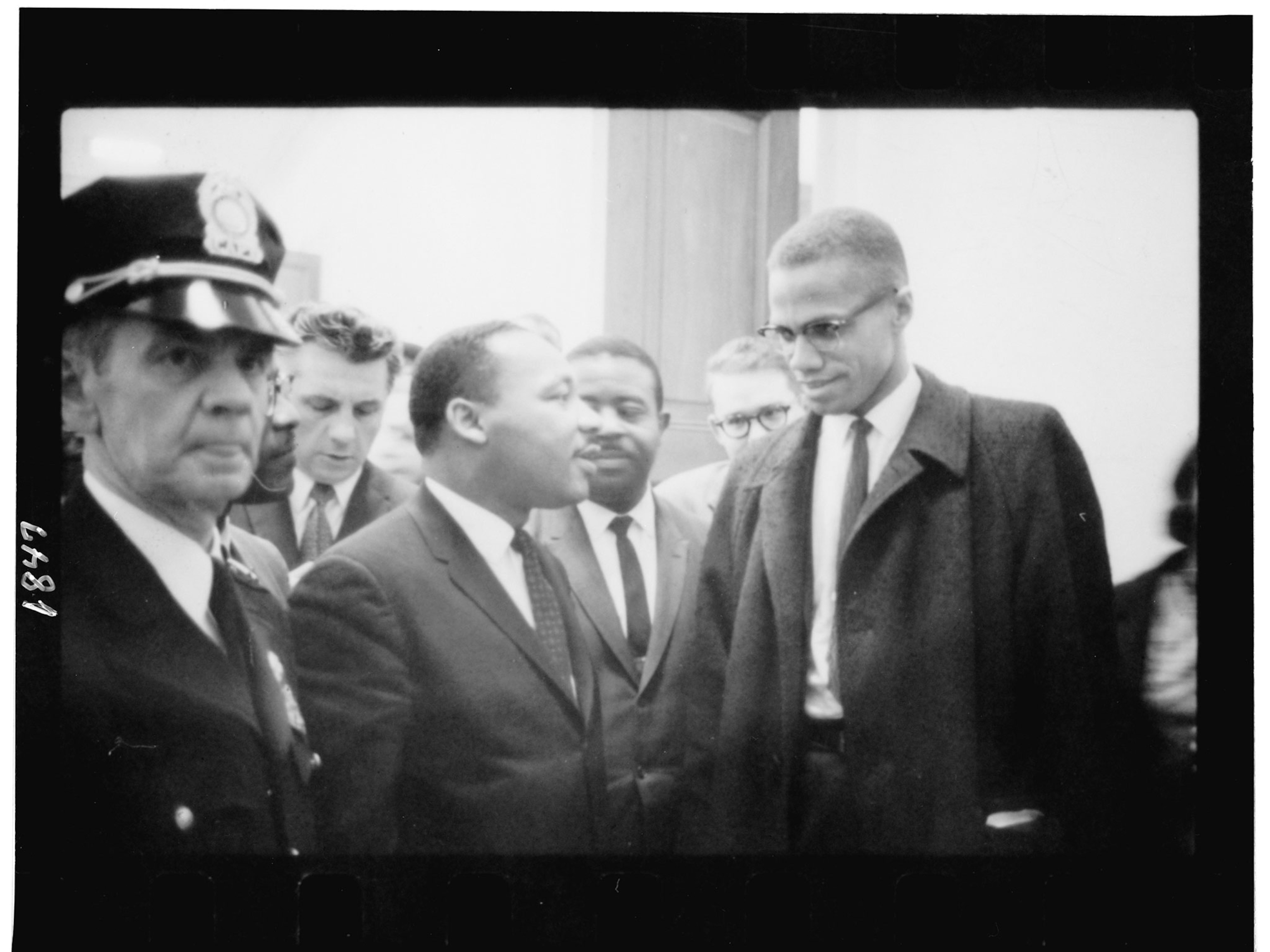

Parks’s decision to resist had been spontaneous, but the response of Montgomery’s Black community was perfectly orchestrated. Word spread about Parks’ arrest, and friends convinced her to allow her arrest to be used as a test case to challenge Alabama segregation laws. Local activists—among them, a young Martin Luther King, Jr.—organized a single-day boycott to coincide with her trial.

Parks was convicted and fined $14 at her trial. While her attorneys appealed her case, the one-day boycott turned into a multi-day protest. Soon, nearly all of Montgomery’s Black bus riders—a full 70 percent of the bus system’s customers—had stopped riding buses.

The nonviolent protest was well-coordinated and efficient, but retaliation was fierce. King’s home was bombed during the boycott, and Parks and others were indicted for violating state anti-boycott laws.

Parks had become a national figure and traveled the country publicizing the boycott. She was en route to a speaking engagement nearly a year after her arrest when she learned segregated busing had been declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court. “Happy to hear of it,” she wrote with characteristic modesty.

(Read more about how American racial justice remains a work in progress.)

Rosa Parks’ activism after the bus boycott

Parks’ activism didn’t end with the Montgomery bus boycott. She moved to Detroit in 1957, but her support of equal rights never wavered. She took part in everything from the March on Washington to the Freedom Summer of 1964, supported the nascent Black Power movement, protested apartheid in South Africa, and worked for Michigan Congressman John Conyers from 1965 to 1988.

By the time Parks died in 2005, she was known as “the mother of the civil rights movement” and a quiet bastion of nonviolent resistance in the face of overwhelming odds. Her coffin lay in state in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. Honored with multiple awards in life and death, Parks is now remembered as a fearless, if unlikely, civil rights leader.

“Mrs. Parks was ideal for the role assigned to her by history,” King later wrote. “She was anchored to that seat by the accumulated indignities of days gone by and the boundless aspirations of generations yet unborn.”