The Nutcracker was a flop. So how did it come to save American ballet?

The timeless show has become a Christmas stalwart and a major source of revenue for ballet companies. But it wasn’t always so successful.

Have you ever been to the ballet? If you answer yes, chances are you saw The Nutcracker—a production so iconic it is often an audience member’s first (and sometimes only) exposure to ballet. The classic, with music by Russian composer Pyotr Ilich Tchaikovsky, is much more than tutus and Christmas trees. It changed—maybe even saved—American ballet more than six decades after its first performance.

Russian roots

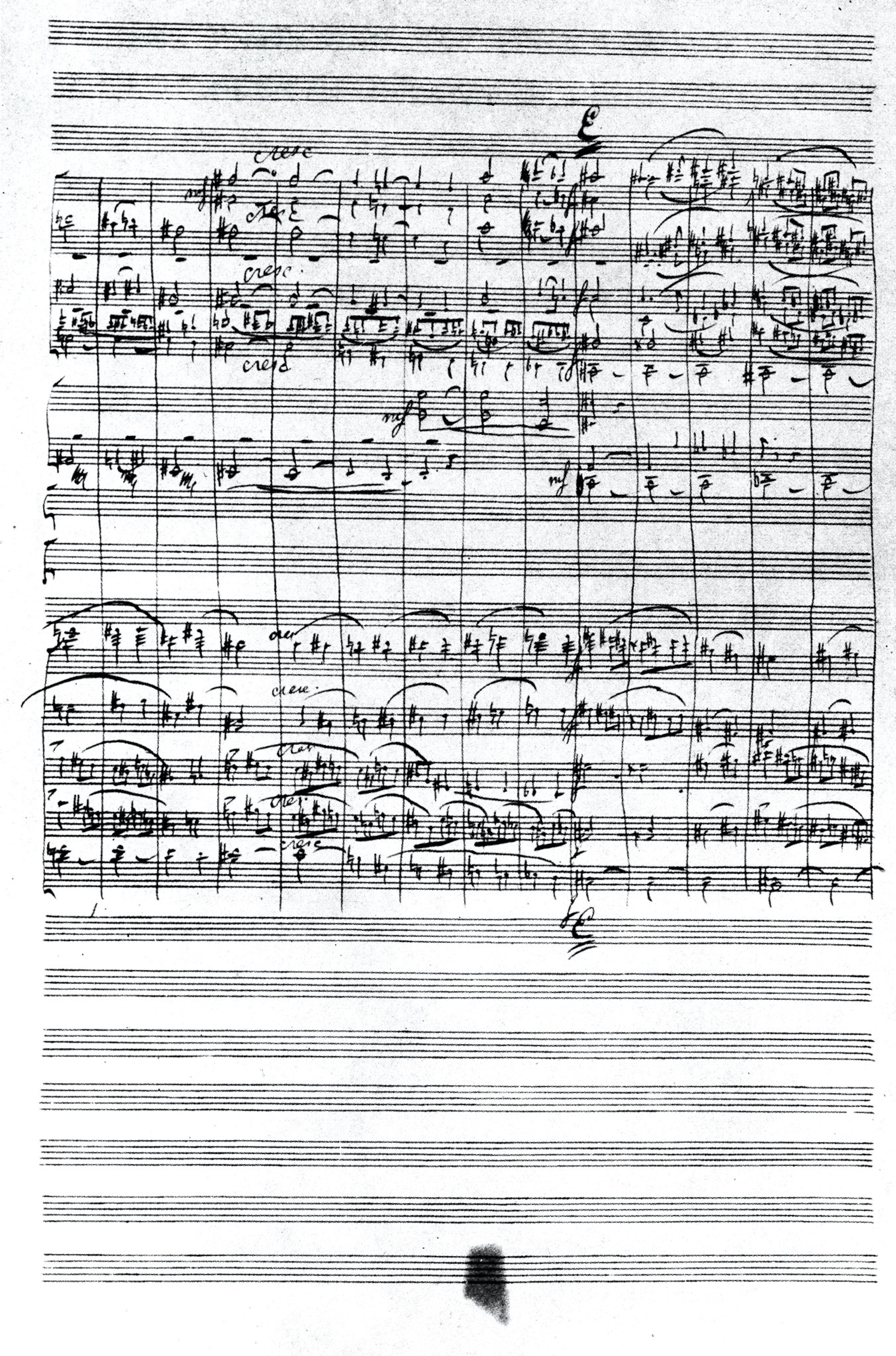

In 1891 The Nutcracker was commissioned by one of Russia’s imperial theaters, state-owned performance venues and companies that held a monopoly over theatrical performances in Russia’s largest cities. Financed by the tsar, these theaters showcased the sophistication and power of Russian culture while ensuring the empire maintained strict control over artistic expression. Tchaikovsky collaborated with Marius Petipa, ballet master and choreographer, writing music to order. He based the score on “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King,” an 1816 novella by Prussian author E.T.A. Hoffmann.

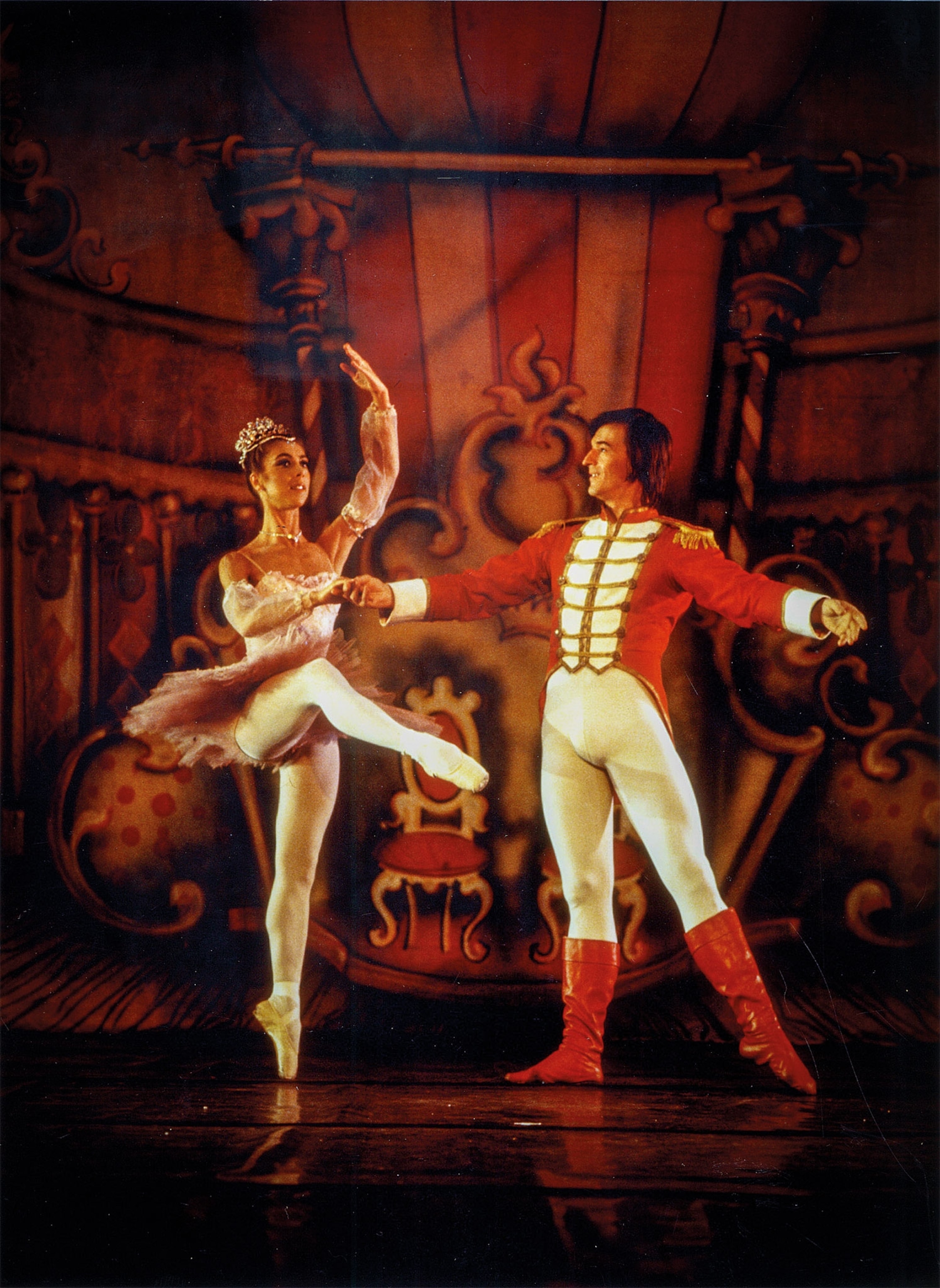

The ballet adaptation tells the story of a German family’s Christmas party where a family friend gives the children a nutcracker. After the family falls asleep, Clara (sometimes called Marie depending on the production) sneaks back to the Christmas tree to see her presents but gets lost in an imaginary world involving a battle between a heroic life-size nutcracker and an evil mouse king. After winning the battle, the nutcracker turns into a prince and takes Clara into a snowy forest.

In the second act, Clara and the Prince watch a cavalcade of anthropomorphized sweets and treats, including Chinese tea, ginger, and chocolate, pay tribute through dance. At the end of the performance, the Sugar Plum Fairy performs a duet with a cavalier, and Clara leaves with the Prince in a flying sleigh.

Although Tchaikovsky had found success presenting an abbreviated version of the score months before the ballet’s debut, audiences seemed indifferent to the first performances in St. Petersburg. Critics disliked the child-centered storyline and the “heavy and wooden” steps of the dancers.

Part of the issue, writes musicologist Damien Mahiet, is that the work was conceived as a ballet-féerie, a fairy story that was light on plot and heavy on musical influences. Unlike other ballets of its time, The Nutcracker emphasized fun and magic, and lacked the tragic majesty of Tchaikovsky’s earlier masterpiece Swan Lake. But later audiences responded to imaginative transformations and human embodiment of natural phenomena—such as snow and flowers—magic that added up to what Mahiet calls its “spectacle of wonder.” As a result, The Nutcracker took off during later productions.

(A highlight in The Nutcracker Suite, the waltz was once a forbidden dance.)

Seasonal but sinister

A new take

The slow-burning success of the ballet prompted its first performance in the United States in 1944, staged by the San Francisco Ballet under director William Christensen. The show rekindled interest in the ballet. But The Nutcracker’s most indelible mark on the fledgling American ballet scene was left by the New York City Ballet in 1954. Reimagined by choreographer George Balanchine, who had grown up dancing it in Russia, the production ditched the traditional Petipa choreography for Balanchine’s soaring steps and exacting stage directions. With the help of a spectacular set and with Balanchine’s ex-wife, prima ballerina Maria Tallchief, originating the new Sugar Plum Fairy, it was a smash hit.

“Everyone in New York was against it, including the critics,” recalled Tallchief. “The company was struggling financially . . . well, thank God we did [stage it], because it saved the company.”

The Nutcracker became a mainstay for the New York City Ballet, and was staged by other ballets over time. It also became synonymous with American ballet, creating a pipeline of new fans.

In the 1970s, the American Ballet Theater took it a step further with a made-for-television staging, this time choreographed and reimagined with a darker, more psychologically complex tone by preeminent ballet dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov. “I’d never choreographed or even staged a ballet before,” he later told Time. “But [the company] needed a commercial success, and that meant a Nutcracker.”

(How Christmas has evolved over centuries.)

A holiday must-have

While most companies stage a wider repertoire throughout the year, The Nutcracker is now a permanent part of American ballet. In 2021, the National Endowment for the Arts reported that ticket sales for The Nutcracker account for about an average of 48 percent of a ballet company’s season revenue— and it is staged hundreds of times each year.

“There’s a certain amount of codependency there,” says Deborah Damast, program director and artistic adviser of the graduate dance education program at NYU Steinhardt. A ballerina and choreographer, Damast tells History it is an essential—and sometimes inescapable—ballet for a company of any size.

“It has all the elements, right? It’s got intrigue. It’s got magic. It’s got candy.” Because of its innate appeal to children, its Christmastime setting, and its showcase of talented dancers in roles like the Sugar Plum Fairy and the Snow Queen, The Nutcracker is often the first—or only—ballet the public sees.

The ballet also enchants dancers who have performed in it. “One of my favorite roles to dance was the snow scene,” Damast says. Tchaikovsky’s music mimics the movements of real snow— and in many productions, fake snowflakes flutter down. “You see swirling and flickering,” she says. “One flake, two flakes, and then a blizzard starts. It’s complex. It’s beautiful. It’s just magical.”

(How Christmas is celebrated around the world.)

Sugary sounds

Sweets and stereotypes

But the ballet is not all magic, especially for those who point out its racial stereotyping and outdated conceptions of nationality and gender. The second act is particularly controversial, given ballet companies’ practice of casting white dancers to perform the Chinese tea segment in yellowface. While some companies have chosen to keep the segment in, movements like Final Bow for Yellowface are challenging directors to portray China through movement, costume, and characterization without racist and demonizing symbols.

Many companies have followed suit, from Pacific Northwest Ballet’s replacement of a male dancer in yellowface with the Green Tea Cricket, an insect normally considered lucky in Chinese culture, to the Scottish National Ballet’s use of traditional Chinese dances during the tea scene. Other productions, like Debbie Allen’s Hot Chocolate Nutcracker and the Hip-Hop Nutcracker, update the score with the likes of Mariah Carey or feature guest artists such as legendary emcee, Kurtis Blow.

(She was an Osage dancer. She was also America’s first prima ballerina.)

Such revisions are criticized by purists who say it is inappropriate to cast modern sensibilities onto ballet. But they are proof of the true flexibility of Tchaikovsky’s masterpiece. “The beauty of The Nutcracker is that it can be imagined and reimagined somewhat like Shakespeare,” Damast, says. Perhaps these new renditions will prompt audiences to attend other ballets, helping dance companies—and the holiday magic they create—endure year after year.